by Gordon Goldsborough

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Link to:

Day 1 | Day 2 | Sources

Hear me speak about this trip in the CBC Abandoned Manitoba radio series. (MP3 audio file)

Join me on a 1,200-kilometre journey from Winnipeg to western Manitoba in a search for an array of historic sites, including grain elevators, museums, monuments, barns, houses, cemeteries, water towers, and bridges. Along the way, we will drive completely around Riding Mountain National Park (but not drive into the park) and pass through several Manitoba communities, including Portage la Prairie, Gladstone, Arden, Eden, McCreary, Laurier, Dauphin, Gilbert Plains, Grandview, Roblin, Shellmouth, Russell, Silverton, Birtle, Shoal Lake, Rapid City, and Brandon.

|

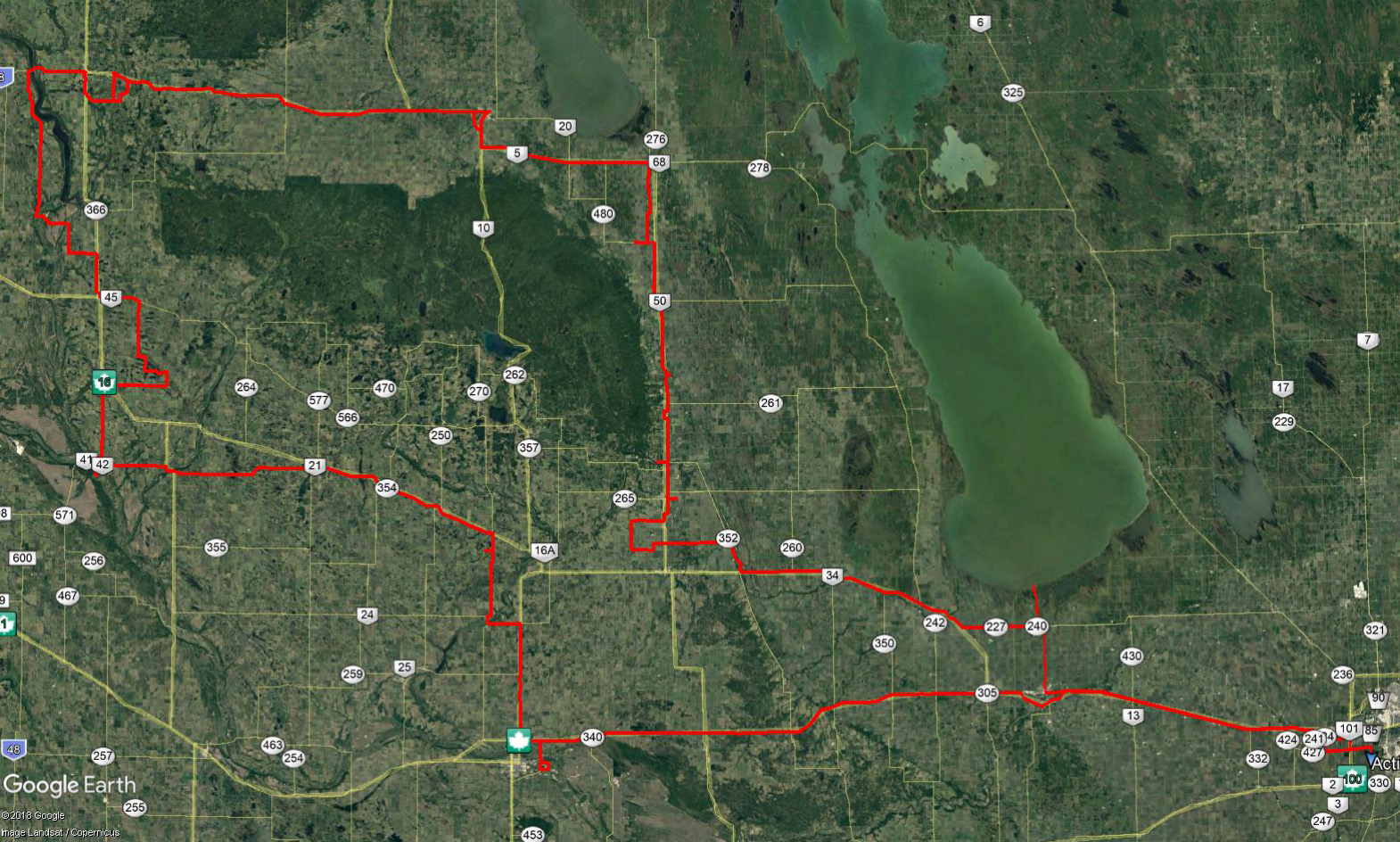

My route shown in red, starting in Winnipeg at right and ending up back there 36 hours later, and driving completely around Riding Mountain National Park |

The trip is a combination of business and pleasure. I have a morning meeting at Delta Beach so I leave home in Winnipeg at 8:30 AM, taking Highway 1 to Portage la Prairie then #240 all the way north to its termination at Lake Manitoba. I arrive at Delta around 10:00. After the disastrous flood of 2011, it looks like things are returning to normal, although a long line of “super sandbags” along the Delta Channel is a reminder that the cottagers remain wary of a repeat. After a couple of hours of productive meetings and a great lunch with Frank Rohwer and Jim Fisher of the Delta Waterfowl Foundation, I leave for points west around 12:30 PM.

|

Delmar Commodities (former Manitoba Pool) grain elevator at Westroc |

I head back south on #240 but not all the way to Portage, instead turning west on #227. I pass through the little village of Oakland and cross the bridge over the Portage Diversion. I sigh a little as I pass the road to the now-closed Delta Marsh Field Station, where I was the Director for 14 years. I arrive at highway #16 (Yellowhead Highway). I love grain elevators so my first stop is to take a few photos of the former Manitoba Pool grain elevator, now owned by Delmar Commodities, along the highway at Westroc. It is an off-track facility, not connected to the CPR Minnedosa Subdivision that passes by it. Trucks can deliver grain there and pick them up, but there is no ability to load grain into railway cars. The logic escapes me. I follow my usual practice of walking entirely around the building to take a photo from each of its four corners. That way, I have photos from all angles as a basis to know when/if changes occur in the future.

|

My drone view of the privately owned (former Manitoba Pool) grain elevator at Arden |

I continue on highway #16, stopping briefly at a convenience store near Gladstone to buy a cold drink. It is already pretty warm. It’s going to be a scorcher. I pass a monument for Big Grass Marsh, the first conservation project of Ducks Unlimited Canada, and the former Salt Plains stockcar race track. Arriving at the junction of highway #352, I turn off to Arden where I have two items on my to-find list: the former Manitoba Pool elevator and the newly-opened Arden Museum. I plan to send up my drone to get a bunch of photos of the elevator, which I notice as I drive closer is starting to look a bit shabby. Numerous panels from its metal cladding are missing. Some of them are strewn around on the ground. I wonder if this is the result of a recent storm or evidence of longer-term neglect? Unlike the Westroc elevator, it still has a railway siding beside it.

|

Former St. Andrew’s United Church, now a community museum at Arden |

Next, I'm on to the Arden Museum that occupies the former St. Andrew’s United Church. It has only been operating for about a year. I would love to stop for a visit but I’m on a tight schedule so I take a few photos and a GPS waypoint (the latitude and longitude that I will need to add the museum to our online searchable database of historic sites) and continue on my way. As I leave town, I cannot help but feel sad. I will always associate Arden with Tracey Winthrop-Meyers, the former Chief Administrative Officer for the Rural Municipality of Lansdowne. For a while, she and her family had operated a business at the old Arden grain elevator to market organic commodities. I met her during a visit in 2012. I needed help to find an obscure historic site and, although she was busy working in her office, she dropped everything and invited me to join her in a two-hour tour of the vicinity. It was country hospitality at its best. Tracey left us far too soon, killed in a car accident earlier this year.

When choosing a route to get from point A to point B, I always pick the “road less travelled.” Rather than return to Highway #16, I use my GPS to calculate a route to the next stop, a monument for a one-room schoolhouse located west of Neepawa. I have configured my GPS to use whatever route is shortest, regardless of the type of road. Sometimes, I have to override it when the selected route looks impassable. But, this time, the east-west municipal route that it recommends is well gravelled and graded. I find It so enjoyable to drive on a country road on a beautiful summer day like this and you never know what you might find along the way. Crossing highway #5 few miles north of Neepawa, in the Rural Municipality of Rosedale, I travel barely a quarter mile when I find a fieldstone cairn on the north side of the road. It marks the site of the former Mountain View School.

|

Fieldstone cairn for the former Mountain View School in the RM of Rosedale |

I have never been here before but I knew about the monument thanks to the late Allan Drysdale, a force of nature when it came to heritage matters in the Neepawa area, and who contributed information about numerous historic sites all over this part of Manitoba. Allan was the archivist for Neepawa’s Beautiful Plains Archives and also curator for the Beautiful Plains Museum. Whenever I had a question about the Neepawa area, Allan was my go-to guy. It is hard to believe that he has been gone for over two years.

I want to get an updated photo of the Mountain View monument from several angles, as well as a closeup of its plaque. Then, I continue another one-and-a-half miles west and three-quarters of a mile south to arrive at my next destination. (By the way, in case you are wondering why I use miles to indicate distance rather than kilometres, the reason is that most roads in the southern part of rural Manitoba are built every mile so it is easy to determine how far you have gone by counting “mile roads.”) Here, I find another fieldstone monument that marks where the Fort Ellice Trail passed through the homestead of early settler John McKee. There are many similar monuments in western Manitoba marking the Trail, which was actually not a single route, but several trails by which people could get to Fort Ellice near St. Lazare, not far from the present-day Saskatchewan border. (I will visit Fort Ellice later on this trip.) Other Fort Ellice Trail monuments are along highway #16 in Neepawa, southwest of Miniota in the RM of Wallace-Woodworth, and in Birtle.

|

Commemorative cairn for the point where the Fort Ellice Trail crossed the McKee farm in the RM of Rosedale |

This particular Fort Ellice monument was first brought to my attention last year by the indefatigable Neil Christoffersen. A retired police officer, Neil is presently Mayor of the Municipality of North Norfolk. I think that he must spend much of his time driving the back roads of Manitoba, judging from how many obscure historic sites he has found and shared with me. Neil is not running for re-election in the municipal elections this fall so I am expecting that he will find many more historic sites when he has more free time on his hands. Thanks, Neil!

The Fort Ellice monument is a little different from the one for Mountain View School. Its stones are larger and, although I am no geologist, they seem more diverse in colour and texture. Some have been split so they have flat sides. This looks like a really professional job that will withstand the ravages of time. Believe me, I have found many monuments that are not so well made and will likely be gone much sooner than their builders planned.

|

Damaged commemorative boulder for Iroquois School in the RM of Rosedale |

A quarter mile south then three miles west brings me to the site of a huge boulder marking the site of Iroquois School. Unfortunately, it looks a little the worse for wear compared to the previous two school monuments I have just visited. The boulder is tilting forward and the stone plaque that was once fastened to its side is gone. It is not hard to tell there was once a plaque there. One of the screws that held it to the boulder was sticking out of the boulder and a rectangular patch of dried silicone marked where it had once been. I wonder if this is the result of vandalism? Many plaques have been stolen because of their value as scrap metal but this one was stone so it had little monetary value. Maybe it was an accidental hit by farm machinery?

|

Commemorative cairn for the former Springhill United Church with the community hall in the background |

My last stop for a monument in the RM of Rosedale is at the recently-mowed site of the former Springhill Church, another fieldstone cairn. It tells me there was a church here from 1891 to 1967 but it does not say what faith it was. After my return home, I dig into Rosedale Remembers, 1884-1984, a local history book published in 1984 that includes a chapter on the Springhill area. It clarifies that it was initially a Methodist church that joined with a Presbyterian church in 1923 to become a United Church. The cairn stands on the former church site, which was demolished after it closed in June 1967. The book lists the names of the people who ministered there through the years. Some of them were ordained and others were students. It also answers my question about the building that I saw in the background behind the church cairn. It was clearly not a church and is much newer. It is a community hall built around 1982.

|

A nice old barn in the RM of Rosedale was built in 1923 by local farmer J. B. Jackson and used for his dairy operation until the late 1970s |

I used to see a lot of barns while travelling through rural Manitoba. Farmers kept their horses and other livestock on the main floor with hay and other feeds in the upstairs loft. Over the past few decades, there has been a pronounced move away from the family mixed farm, so farms today grow crops or animals but usually not both. This has doomed many of the old barns. A couple of years ago, I collaborated with the Manitoba Co-operator, the weekly farm newspaper, in a project to see how many of the barns that were featured in the Co-operator in the 1980s were still standing. Each week, the Co-operator would publish a photo of a particular barn and ask readers to contact me if they knew where it was located and whether or not it was still standing.

One of the barns featured in this series was the Jackson Barn about a mile and a half south of the village of Eden. Built in 1923 for a farmer named J. B. Jackson, the loft was used for local dances until the 1930s. The Jacksons renovated it into a dairy barn and operated it until 1979, shortly after a new steel roof replaced the original cedar shingles. That roof made the barn clearly visible from highway #5 as I drive closer. The owners contacted me, after seeing their barn in the Co-operator in December 2014, to report that was still in active use for accommodating livestock. That was good to hear because, otherwise, we found that many of the barns in the Co-operator series had been demolished since the 1980s, a sign of changing times in Manitoba agriculture.

|

A little east of Eden, I found a former maintenance building for a Relief Field of the Second World War training facility at Neepawa |

About a mile east of Eden, I find a former Relief Field for the Elementary Flight Training School near Neepawa. It was a facility of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan during the Second World War, in which military personnel from all over the British Commonwealth, as well as few Americans and others, came to Canada to be trained as pilots, navigators, and bombardiers. The idea of a Relief Field was that if, in the course of a training flight, an aircraft was unable to return to the main airfield because of inclement weather or a mechanical failure, they could land at the Relief Field. Usually, these fields were smaller and much less well equipped than the main one. Most signs of these Relief Fields have been obliterated in the decades since the war ended but, in some cases, I have found concrete runways, hangars, water storage tanks buried in the ground, and other features. One of my personal favourites is the Chater Relief Field, northeast of Brandon in the Rural Municipality of Elton, where a nice old hangar and some of the original runways are still present. The only remaining feature of the one at Eden is a maintenance building which, as long as it stands, provides a visible reminder of Canada’s contribution to the war effort. It looks like the site is still being used as a mechanical shop for farm equipment, being surrounded by numerous combines and pickup trucks in various stages of disassembly.

|

A massive boulder marks the former site of Big Valley School part-way into a deep valley |

After leaving Eden and travelling three and a half miles north on highway #5, I turn off onto to the west side of the highway and drive about a mile and a half on a good gravel road. My next destination is the former site of Big Valley School. I knew the school had sat on the north side of a valley for one of the many small streams that originate in Riding Mountain National Park. However, I did not realize how deep that valley was until the GPS told me to turn onto a trail leading downward at a rather steep angle. Part-way to the valley bottom is a flat clearing in the trees where there is a massive boulder marking the school site and a nice metal park bench for relaxing, having a picnic, and enjoying the scenery of this picturesque little valley. I am continually amazed where, at one time, there were enough school-age children to warrant opening a school. Today, I doubt there are more than a handful of kids within a dozen miles of here but, at one time, Big Valley had up to 30 students. It closed in 1958 and henceforth local children were bused to the school in Eden.

|

The fieldstone cairn for the former Tobarmore School features a miniature model of the schoolhouse |

After taking photos and a GPS waypoint at Big Valley, my little car has to work hard to climb back up the steep road to return to highway #5. Almost exactly three miles north is a fieldstone cairn on the east side of the highway for the former Tobarmore School. An enterprising local resident has put a small shack beside the cairn. Inside it are bundles of firewood being sold on the honour system, with purchasers expected to leave their money while taking wood. I wondered if any of them stopped to look at the cairn?

Unlike the other school monuments that I have visited today, the one for Tobarmore is a little different. On top of the fieldstone cairn is a little model of the former schoolhouse. Screwed to the side of the cairn is a small metal plaque listing the names of three men. My guess is they were the ones who built the monument. My research in advance of the trip indicated that, after the school closed in January 1968, the building was moved three miles north to the village of Riding Mountain and turned into a community centre. I wonder if it is still in use?

I use Google Earth as one of my main tools to search for historic sites from the comfort of my home office. Sometimes, it is possible to see monuments, buildings, and other structures in satellite photos and obtain approximate latitude and longitude for them. Cemeteries are usually quite easy to find because the regular patterns of headstones are quite distinct. Concrete-topped graves are especially easy to see, though they are roundly hated by those who have to mow around them while maintaining a cemetery. Some cemeteries now expressly forbid concrete-topped graves for this reason.

|

The cemetery near Riding Mountain features a newly-built gazebo |

My next four sites are cemeteries that straddle highway #5 on the stretch between Riding Mountain and Laurier. The first one is near Riding Mountain, located about a mile as the crow flies northwest of the village. It is easy to find: a half mile west on a municipal road then a half mile north. Unlike some that I have found, it is nicely tended and appears to have had quite a lot of recent construction work done. Two concrete posts mark the entrance. One bears a sign announcing the name of the cemetery while the other commemorates Jeffrey Bruce “Jeff” Kirk, who died in 2012 at the age of 51. A photo of Mr. Kirk is etched into a stone tablet fastened to the post and the inscription makes it the sound like he left money in his will for the cemetery. Perhaps that was what enabled the construction of a concrete and wood gazebo – clearly recent based on the newness of the wood – farther into the cemetery? Later, I find an obituary for Mr. Kirk in the Neepawa Banner. It says that he started a career with Canada Post at the office in Riding Mountain before being transferred successively to offices at Onanole, Reston, Melita, and finally Erickson.

A modest metal archway sign near the gazebo, also bearing the cemetery’s name, probably was an earlier marker for the cemetery entrance, displaced by the present new one. Near the archway are three concrete-topped graves that catch my eye. They are covered in orange speckles. I have noticed in my travels that older concrete is often covered in orange-coloured crusts of lichen. Not just grave markers but also bridges and other structures made from concrete. They have to be old because lichen grows slowly so only old concrete would have amassed enough time for the lichen to become established. Whenever I find lichen growing on old concrete, it is invariably orange, which likely indicates it is a particular species. It is an amazingly consistent finding that I have seen all over Manitoba, in cemeteries and elsewhere. For example, look at the arches of an old bowstring arch bridge near Souris – they are bright orange. As a professional biologist myself (but not a specialist on lichens), I am curious about the basis for this particular lichen’s preference for concrete. I wonder if a scientist somewhere has studied the phenomenon? Maybe I will ... someday.

|

The former elementary school at Kelwood, later used by an automotive business, but now looking sad and vacant |

The next cemetery on my itineray is at Kelwood. As I turn off highway #5 heading east, I pass the old Kelwood Elementary School building. I do not know much about its history but, judging from its architectural style, I would date it to the 1970s or 1980s. The western part of the building looks like it was torn off, with a jagged edge where the concrete blocks of the remaining building were once attached to those of the missing part. The school has been closed for some time and, for a while, the building was used by a business whose sign over the main entrance advertised services in towing, auto sales and leasing, vehicle repairs, and sale of new and used parts, and new and used tires. A website address on the sign is no longer in service which seems consistent with the abandoned look of the place. There must be a story here to be told. I wonder what it is?

|

The entrance to Kelwood Cemetery |

Several of the buildings in Kelwood have colourful murals resembling quilts on their exteriors. Driving past them to arrive at the entrance into the Kelwood Cemetery, I see that it is one of those prohibiting concrete-topped graves. A sign displayed prominently on one of the entry posts announces that “No cement covers allowed on graves.” The policy is clearly not retroactive because, within eyesight of the entrance, I can see several graves with concrete tops. I already have a latitude and longitude reading for the cemetery, based on measurements using Google Earth but I check those coordinates using my own GPS receiver and wander around the cemetery for a few minutes, taking several photos.

|

Numerous mature deciduous and coniferous trees surround the beautiful McCreary Cemetery |

Nobody is going to overlook the cemetery at McCreary, located about two miles north of town. I already have GPS coordinates for it but, even if I did not, a large metal sign along highway #5 advises me where to turn. A half mile to the west is an attractive site surrounded by tall, mature trees. Recently trimmed pines near the entrance give off a characteristic scent that I really love. Following my usual routine, I check my coordinates by taking a new GPS waypoint, photograph the entrance sign, and take a few photos within the cemetery. Then, I am back in the car for another six miles north on highway #5, leaving the RM of Rosedale and entering the RM of Ste. Rose. I turn west onto highway #480 and another two miles takes me into the village of Laurier. I have been here several times before but I have never managed to get a photo of its cemetery, on the west edge of town.

|

Mature oaks in the Laurier Cemetery |

Like a lot of cemeteries in rural Manitoba, the Laurier Cemetery was built with a large population in mind, judging from the amount of land it occupies. All the graves are at its western end except for a row of graves parallel to the road. At the end of this row, nearest the entrance driveway, is a curious little grave marker that looks like it is being pushed over by a shrub behind it. On its face is a brief narrative that seems to state the obvious: “Ici repose le corp de Theo. Bonin decéde Fev. 3 1946.“

At this point, I have to make a decision on my continued route. I could return to highway #5 and drive quickly and smoothly on pavement to Dauphin, or I could detour on a gravelled route to check out an old bridge that I saw on a previous trip. Of course, I choose the latter. Interestingly, the turnoff from highway #480, one mile before getting back to #5, has a sign that confirms what I already know about this municipal road: “Old No. 5 South.” We tend to think that provincial highways have always followed their present-day routes but this is frequently not true. In this case, highway #5 used to be one mile west of its present course. It was a more winding route that crossed a river at least once on its way to Ste. Rose du Lac. At some point, highway engineers decided to move it eastward to the present location. In the process, they abandoned a wonderful old bowstring arch bridge, one of only six remaining in the province. Do I want to see it? You bet! Who knows how much longer it will survive? It may suffer the same fate as its cousin on highway #3A outside of Clearwater that, earlier this year, was removed by Manitoba Infrastructure. That bridge, built between 1919 and 1920, was featured on the cover of the Fall 2013 issue of Manitoba History magazine.

|

A rare bowstring arch bridge over the Turtle River on an abandoned section of provincial highway #5, south of Ste. Rose du Lac |

Why do I love old bridges so much? I suppose it is because of the back story that they represent. We take for granted that we can jump in our cars in Winnipeg and, like I did today, drive to Dauphin in the course of a single day. This would have been impossible to Manitoba drivers a century ago. Not only were the roads primitive by modern standards, there were numerous places where the road crossed a river. Sometimes, there was a ferry to enable people to get across. In other cases, one might have to drive miles out of the way to find a bridge. As numerous bridges were built in the early 20th century, the highway network that we enjoy today took shape. In my view, bridges are fundamentally important to this development. Some of them, such as the bowstring arch style that is so-called because it resembles the archer’s bow, are also quite attractive (in my admittedly biased opinion).

Was the old bowstring arch bridge still there on that abandoned stretch of provincial highway? Yes, it was! Although I have stopped to admire it several times, it never gets old for me. Lest anyone dispute its age, clear evidence is stamped into concrete posts at either end of the bridge: the number 1921, its year of construction. The sun is starting to descend in the west and the western arch is bathed in glorious sunshine. Leaving my car on the side of the road so it would not be in the way of a photo, I hack through tall weeds growing along the Turtle River until I get to a spot where the entire bridge is visible. I take several photos and debate about sending up my drone for some aerials before deciding to forego them in favour of getting back on the road more quickly. The weather to this point has been outstanding – bright and sunny – but who knows how much longer it will last? The main purpose of this entire trip is to get photos, under good light conditions, of a site near Roblin and it is still 90 minutes away with the sun getting lower in the sky. The next day's weather forecast is iffy, possibly sun mixed with clouds that would make for poorer photos. Consequently, I head straight north and rejoin highway #5 as it turns west a little past Ste. Rose du Lac.

My final stop for the evening is located 140 kilometres from my present location. It is 6:00 PM so that means, if all goes well, I will arrive at the site of the former Grainfields School around 7:30 PM. My GPS calculates that sunset will occur today at 9:58 PM so that should give me plenty of light to get photos. If it rains tomorrow, I may not be able to get decent photos and I really, really need them. The reason is that I am putting finishing touches to my latest book, More Abandoned Manitoba, and it will include a chapter about the practice of growing shelterbelts – a fringe of trees grown to protect homes, churches, schools, and other buildings from exposure on the windswept prairies. I want a photo to illustrate how extensive shelterbelts can become, especially when they are left to grow untended, and I can think of no better place than Grainfields School. When I first visited it in 2012, I was convinced that my coordinates were wrong. I arrived at the site to find an inpenetrable bush where I had expected, based on my research, to find an abandoned schoolhouse building. I walked around the edge of the bush but could see nothing within resembling a building. It turned out that I was too easily dissuaded. When I returned home, I entered my “wrong” coordinates into Google Earth and it showed me a satellite image for that spot. Lo and behold, there was a building roof visible amongst all that foliage. I made a note in my “to-find” list to try again during my next visit to that area. In 2013, I was back and, this time, I bushwhacked through dense Caragana bushes to find a nice, little one-room schoolhouse hidden and awaiting my visit. When I found an historical photo of the school taken around 1930, it showed small bushes that had been recently planted all around the school. Clearly, they had thrived.

My first order of business is to get some aerial photos. I assemble my drone, fire it up, and send it into the sky on the west side of the shelterbelt. It is nearly 8:00 PM and the trees are throwing lengthy shadows. Undeterred, I take 50 photos from various angles, including several looking straight down at the schoolhouse building surrounded by vegetation. Then, I bring the drone back and, before landing, take a photo of myself standing on the road near the shelterbelt. I had made it – mission accomplished. If I accomplish nothing else on this trip, I now have some photos for use my book. I pack up the drone, take a few ground photos, and pile back into my car. My accommodations in Dauphin are an hour’s drive away, and I desperately need a shower, a meal, and a cold beer, not necessarily in that order.

|

At the end of a successful day of field work, with the sun setting behind my hovering drone, I took this photo with the Grainfields School shelterbelt in the background |

|

As we see in this aerial view, the former Grainfields School building is almost completely hidden by dense foliage |

Despite yesterday’s gloomy weather forecast, I awake in Dauphin to glorious sunshine. Rather than head out on the road immediately, I decide to hold back until 9:00 AM so I will have mid-morning sun by the time I return to the site of Grainfields School. This turns out to be the right decision, as the light is perfect when I arrive back there. I send up my drone and the roof of the schoolhouse is visible amongst the dense foliage. Several vehicles pass by as I am taking photos and I wonder if they are curious why I am flying a drone at wat they probably think is an innocuous place. Walking around the edge of the shelterbelt, the dense Caragana bushes remind me why I had trouble finding the school in the first place. They are really, really dense – almost impenetrable.

|

A pony truss bridge over the Shell River in the Municipality of Roblin |

My next destination is on the far side of Lake of the Prairies so I have two ways that I could get there, along the east side or the west side. The east route is shorter and would not take me through Roblin but I decide to take the longer west route. I'm glad I did because, as I approach the Shell River on highway #583, I see an old pony truss bridge. These sort of serendipitous finds are what make the travels so much fun. What is a pony truss bridge, you ask? A formal engineering definition: “Steel trusses on each side of the bridge rise above the deck and there are no cross connections between the top cords.” In other words, there are steel trusses on each side of the bridge as you cross but there are no steel beams above you, unlike a steel through-truss bridge such as the Arlington Bridge in Winnipeg. There are no identifying marks on this bridge, such as a plate fastened to one of the trusses by its maker, so I cannot immediately tell who made it or when. However, it looks a lot like another pony truss bridge over the Shell River northeast of Roblin. That one was built by Dominion Bridge of Winnipeg so my first guess is that the two bridges are more or less contemporaneous. A reasonable guess is that the bridge dates from the 1920s or early 1930s, possibly earlier. I will have to do some digging in the archives when I get home to see if I can put a more accurate date on it.

As I pass through Roblin, I debate whether or not I should check out a few buildings for which I do not have photos, such as churches, but I decide against it. I have a lot of other places to go today. On the westward drive on highway #5, I pass several familiar spots: the community hall at Cromarty that used to be a one-room school and an unusual conical stone monument commemorating the Pelly Trail. The crossing of the Lake of the Prairies reminds me a little of the Okanagan Valley – a long, narrow lake in a valley. Too bad we could not grow grapes on the slopes of that valley! On the west side, part-way up the hill is the turnoff to highway #482. I have not spent much time in this area and I suppose that I should but it will have to wait until another trip.

|

Commemorative sign for the former Grainsby School in the Municipality of Riding Mountain West |

About 14 miles south, highway #482 turns to the east. Instead of following it, I continue straight south onto a gravelled road. My reason is there is a sign a few hundred feet south of the highway that is on my to-find list. I saw it when I was looking at the spot with Google Streetview. The sign was near where the former Grainsby School had operated so I wondered if it might be a commemoration for the school. As I drive near, I find that my guess is correct. It is a metal commemorative sign. When I photograph such signs, I try to include, along with the sign, a view of the site itself where the schoolyard was once located. There might be some remains of the school too, such as bits of its concrete or stone foundation, some steps, or an old well. Here, I find nothing. So I take several photos and a GPS waypoint and return to my car. Should I return to highway #482? I ask my GPS for its advice, given my next stop, and it suggests that I continue south on the gravelled road. Who knows what I may find going that way?

The next stop, a cemetery southeast of the village of Shellmouth past the Shellmouth United Church, was brought to my attention by Don Burroughs, whose ancestors homesteaded in this area. Don sent me its coordinates and I must admit that I was initially skeptical. The cemetery is rather far from the village, at least a mile and a half, along what looks like little more than a trail. I am pleasantly surprised to find the trail to be newly graded with a decent layer of gravel so it presents no challenges to my little car. Don’s coordinates turn out to be spot on although I miss the site at first because it is slightly off the road to the west. I back up and pull my car off the road. The cemetery is a short walk to the northwest. A detail that was not visible in the Google Earth view of the site is that the cemetery sits atop a small hill, surrounded by a modest fence, with a panoramic view of the surrounding countryside.

|

Monument in the Shellmouth Pioneers Cemetery in the Municipality of Riding Mountain West |

Inside the cemetery, grave markers poke out of long grass here and there, and there is a fieldstone cairn near some short shrubs. Entering the cemetery, I see that a plaque attached to the cairn has a list of names and dates, probably the people who are buried here. The first name on the list is James Burroughs, born in 1833 and died in 1900. His wife, referred to by the convention of the time as Mrs. James Burroughs, is below him: 1839 to 1917. Other surnames include Cochrane, Dunseith, Fisher, Garnett, Gerrard, Graham, Holmes, McFadyen (lots of them), Nevill, Pierpont, Plaskitt, Switzer, Stennet, and Yeates. Most of the death dates are in the early 20th century although there is one from 1983. Don later tells me that Hugh McFadyen, a former leader of the provincial Progressive Conservatives, is a descendant of the McFadyens buried here. The official name is St. Cuthbert Anglican Cemetery but I think the title of “Shellmouth Pioneers Cemetery” is more descriptive.

I assume that, in calculating the route to my next stop, my GPS will recommend for me to go back the way I had come. Instead, it instructs me to continue along the road to the cemetery. That turns out to be the right decision, as it is a good road, at least when it is dry. Three miles east brings me to a good road going north-south so I turn onto it. As I drive south, ahead I can see a bright-red object on the left side of the road. At first, I cannot tell what it is. As I get nearer, I realize it is the metal roof of a small building. It turns out to be a former one-room schoolhouse: Endcliffe School.

|

The former Endcliffe School in the Municipality of Riding Mountain West |

I have visited Endcliffe School before, almost exactly six years ago, in June 2012. At that time, the large bank of south-facing windows were uncovered and I could peak inside. Now, the windows have been covered by sheets of plywood. They have probably been broken by vandals. Otherwise, the site is well tended. The grass has been recently mowed, even under the pair of swings in the former playground. There is a new-looking Canadian flag flying on the flagpole. If not for the boarded-up windows, I could imagine the school was still in business. A metal sign beside the building explains the basis for its name, chosen by local resident Bill Pagan for his home in Yorkshire, England. It says the school district was organized in April 1909 and dissolved in January 1968 when its catchment area became part of the Pelly Trail School Division.

Four miles east brings me to highway #83 which would have been my route if I had decided earlier to go down the east side of Lake of the Prairies. From here, it is just five miles to the edge of Russell where I have four things to find. Two of them are easy because they tower over the community and are readily visible: the water tower and the town’s sole remaining grain elevator. Some may think the water tower is not especially “historic” but I have heard it will be taken out of service this year, if not already.

|

The soon-to-be-historic water tower at Russell |

Water towers were once common in towns around Manitoba. They provide a reliable supply of water, especially during emergencies such as fires when a large quantity is required, and they provide water pressure to distribute water throughout the community. Water towers are being replaced by variable-speed pumps that provide the same water pressure at a lower cost. The water towers in Boissevain, Brandon, Carberry, Deloraine, Killarney, Manitou, Portage la Prairie, Rivers, Winkler, Winnipeg, and Winnipeg Beach are already sitting idle. It is a matter of time until the remaining ones are shut down too. So I want to take photos of the one at Russell while I still can.

|

Russell’s last grain elevator |

Just down the street from the water tower is a former Manitoba Pool grain elevator. Built in 1974, it had a relatively short life before being closed and sold to a local farm family in 1997. The railway tracks that serviced it have been removed so it is dependent on trucks to deliver and receive grain. My other two stops in Russell are likely to be troublesome. One is a plaque commemorating local pioneer Charles Arkoll Boulton. I have an address for it (135 Pelly Avenue North) but the address turns out to be invalid – there is no Pelly Avenue North, just Pelly Avenue and Pelly Avenue South. The other plaque, commemorating the centenary of the Russell Agricultural Society, is a complete mystery. I have no idea where to find it. I do not have a lot of time so I decide to skip both of them for another time. Time for lunch. I opt to go through a drive-through on highway #16 at Russell. The food is not great but I cannot beat the speed with which it is served. I am back on the road and will hold off eating until I get to my next stop.

The smell eminating from the bag on the seat beside me proves too enticing so I sneak a few french fries on the way to the next stop, five miles to the east along highway #45. There isqq not much to be said about the village of Silverton these days. There is a former one-room schoolhouse and a United Church. The attraction for me is a grain elevator that once belonged to United Grain Growers.

|

An aerial view of the former UGG grain elevator at Silverton reveals its former paint colours |

I have not stopped to look at this elevator before but the photo sent to me two years ago by Bernadine Brown of Rossburn suggests it may be interesting. Compared to a photo taken in July 1992, a lot of the elevator’s exterior paint has flaked off. Repainting an elevator is a costly undertaking and clearly not one that the owner of this elevator sees as a priority. Whereas in 1992 it had the usual white and blue colour scheme of United Grain Growers, by 2000 some of the former paint scheme was showing through. It featured an interesting checkerboard pattern near the top of the elevator and a rather different corporate logo than the UGG one that was common by the 1980s. In Bernadine’s photo from 2016, a lot more of the paint was gone so more of the earlier details were visible. As I rolled up, it is clear that even more of that earlier “ghost sign” is now visible. The sun is in the perfect direction to put most of the sign in bright light so I set the prospect of lunch aside for a moment and pull out the drone for some aerial photos. After flying around the elevator to get views from several angles, and walking around it to get my usual “four corner” photos, my last step is to peek into a window of the small, detached building that stands beside the elevator. It had once been the office of the elevator agent, the only part of the facility to be heated in winter. It does not look to be recently used and, in fact, the entire place has the air of abandonment about it. Not surprisingly, there is a padlock on office door. Turned toward a door leading into the elevator, I notice with surprise that that door is not locked. I take a photo (to remind myself later that the door was unlocked) then take a quick peak inside. The cooing sounds of many pigeons greets my ears. They are probably not its only inhabitants but certainly its most vocal ones. It is hard to tell if the elevator is still being used but I may get my answer when I compare my photos of the elevator to one taken by my friend Jean McManus in September 2014. At that time, there was nothing on the west end of the elevator. Now, there are several steel tanks. My guess is they have replaced the storage function of the old elevator.

After wolfing down lunch while sitting beside the elevator in my car, I think about what the future holds for this little elevator. If I am right, and it is no longer in active use, there will be motivation to remove it. The high cost of demolition will be the only disincentive. For now, it is still part of my Grain Elevator Countdown, an interactive map on the MHS website that lists all the remaining wooden grain elevators around the province. The tally stands at 133.

Now the tough part of the day starts. I am trying to find a monument for the Lidcliffe Conservation Project, situated about ten miles south of Silverton. It was a marsh restoration project undertaken by Ducks Unlimited Canada, probably in the 1980s but I cannot be sure. Normally, when DUC does a project like this one, with funding from contributors in the United States, a monument is put up somewhere in the area. An example that I have found (completely by accident) is the Granvel Salmon Monument in the RM of Minto-Odanah southeast of Minnedosa. Unfortunately, no records have been kept of the locations of these monuments with the result that I have a couple dozen Ducks Unlimited monuments on my to-find list. Before I headed out on the road, I had done some research to see if I could narrow down the possible monument site. I reasoned that it was close to the Lidcliffe Community Hall whose monument I had mapped back in June 2012. My map indicated there was a conservation area south of the hall’s former location so that was where I planned to start my search. The difficult part, especially when I am travelling alone, is these monuments are often not installed near a road so it may not be readily visible from my vantage point in the car. To search for a monument while driving takes a slow speed and quick eye. I drive south then turn east, looking from side to side as I go, passing the area where I had hoped that I might find the monument. I have gone three miles now and still no sign of a monument. Then, out of the corner of my eye, I see a sign partially obscured by bushes. I think it has the distinctive Ducks Unlimited logo on it. I stop, back up slowly, and look. Yup, it is a sign for the Lidcliffe project. But it is not a monument. I reason that maybe the sign merely announces the site but the monument is actually farther in. So I turn off the road and drive in an overgrown driveway into what I suspect was once a farmyard. The sign had warned that the site was only accessible by foot so, although the driveway looks dry, I leave my car and walk a short distance into the property. I see another sign and walk to it, but find that it is only another similar to the one by the road. I could keep searching but I decide that it is not worth spending a lot of time that may ultimately prove to be futile. I abandon the search and return to my car. As I drive away, I continue to watch from side to side in case my impatience means that I miss the monument. Still nothing. Oh well, another time. The sun is still shining brightly and I want to get some photos at Fort Ellice so I stop looking for Lidcliffe and pick up the pace.

I drive ten miles west, back to highway #16 then turn south for another ten miles to reach highway #42. That one takes me into St. Lazare, a picturesque little town in the bottom of the Assiniboine River valley. I drive slowly through town, noting that it does not look as prosperous as during my previous visits. As I pass a grocery store, the prospect of stopping for a cold drink pops briefly into my mind, but I put it aside as I continue over the railway tracks and follow a curving road heading west. Climbing up the west side of the valley, I turn south onto a small gravel road that goes in a southeasterly direction, passing a few homes and farms along the way, until it enters some woods. I recall the spot very well. In one of my earlier visits, there was a large sign here, beside a cattle gate, that advised everyone that they were entering private property and should stay out unless they had permission. Now, however, that ominous sign has been replaced by a friendlier one saying that the property is now owned by the Nature Conservancy of Canada. I do not think they want a lot of visitors but they are not as intent on keeping out visitors as the preceding owners. Shortly after passing the sign, I turn onto a small road that angles back the way I came as it heads up a steep incline. Rainwater has gushed down this road sometime in the past, leaving small gullies in the road that I have to slalom around as I drive. Taking it easy, I get to the top of the valley and the road disappears into an open expanse of prairie.

|

A portion of the panoramic view from the west side of the Assiniboine River valley, the former site of the Fort Ellice fur trade post |

This is the former site of Fort Ellice, a fur trade post of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Initially, the post was established farther west but was later moved here. If there were not a lot of small trees growing up on the valley slope, the spot would have a commanding view of the meandering Assiniboine River far below. I am here to capture some of that view with my drone. My first photo is aimed straight east, toward the river. A commemorative stone cairn that was erected at the site in the 1930s is visible in the foreground. As I slowly turn the drone in a clockwise direction, I take a series of photos, each overlapping somewhat with the preceding one. This way, I will be able to blend individual photos together using computer software to create a seamless mosaic of the panoramic view. I have been here a few times so there is no need to explore the site more fully but I do take a few photos on the ground of the cairn, noticing that the trees are notably taller now than in a photo of it taken in 2002. To the north of the site, amongst trees, is a former Fort Ellice cemetery where some of the more prosperous people (or, at least, those who could afford stone headstones) were buried. It has mostly been reclaimed by the forest but a few stones are still visible.

Driving back down the rutted little road, then back along the valley to the highway, I again pass through St. Lazare and climb out the east side of the Assinboine valley on my way to Birtle. It is a short trip, only about twelve miles on highway #42. My objective on reaching Birtle will be to get photos of several historic buildings. They are ones that have been identified by Birtle’s Municipal Heritage Advisory Committee (MHAC) as being historically important. In theory, municipalities around Manitoba are supposed to have MHACs to advise them on heritage-related matters. There are only a handful of active MHACs but Birtle has done quite a lot of work. I have addresses and coordinates for several buildings – six homes and one business block – that I want to photograph. It is now 3:30 PM so the sun is mainly from the southwest. I worry that it may be too late in the date to get well-lighted photos of many of the buildings. It turns out that my worries are without basis. With one exception, late afternoon turns out to be a very good time to photograph most of them.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Stone features prominently in the construction of several buildings. Some were the work of master mason Charles Dunham. The Corr House, a two-storey residence on the east side of town, really draws my attention. Built in 1902, it was made of locally-cast concrete blocks. I am especially fascinated by concrete buildings because they were an ingenious solution to the problem of building a fireproof, insect-proof structure using local materials without the need for a kiln (such as would be needed for making bricks) or access to quarriable stone deposits. Curiously, concrete block buildings were only popular for a dozen years or so in the early 20th century so, when one sees a building made from them, its age is fairly easy to estimate. It turned out that the object of my admiration is owned by the Hasselstrom family. Although I have not previously met Rev. Hasselstrom or his wife, I am acquainted with their son Nathan, who is presently completing graduate studies (in History) in eastern Canada. I had met him a couple of years ago while doing research on the Indian Residential School at Birtle and seeking access to the archival collections at the Birdtail Country Museum, itself housed in an historic building in downtown Birtle. At that time, Nathan was the summer curator for the museum and was a big help in my research.

|

The former United Grain Growers elevator at Shoal Lake, now privately owned |

|

The former Manitoba Pool elevator at Shoal Lake, now privately owned |

After buying a cold drink that I had missed in St. Lazare, I depart Birtle and head east on highway #42. My eyes are peeled for a small family grain elevator that I was told a few months ago stands somewhere between Birtle and Shoal Lake. I was not told where exactly it is located, not even on what side of the highway. Consequently, it comes as no shock that I cannot find it. Later, I learn that it was much closer to Birtle than I had assumed. It is now on my to-find list for a future visit to this area. The late afternoon light is still good so I take advantage of the opportunity to re-photograph the two wooden grain elevators in Shoal Lake. (I skip the newer concrete one on the west side of town.) I have photographed these elevators before but I see no reason to lose a chance to get well-lighted photos, especially if the subject may be gone in the not-too-distant future. Formerly corporate elevators owned by United Grain Growers and Manitoba Pool, respectively, they are both now owned privately. The former UGG elevator looks to be in good condition but I am not so hopeful about the Pool elevator. It is missing several panels from its metal cladding. This is often the first clue that maintenance is being neglected by its owners, on the road to eventual demolition.

I have one more frustating site to search for, another Ducks Unlimited monument. Supposedly, it is located somewhere near the unfortunately named Dirty Lake, south of Basswood. It is a short drive along highway #16, passing along the way a small grain elevator at Glossop that has gone through several changes of ownership – and changes in paint – during its history. The current version is a black-and-white colour scheme for Parrish & Heimbecker but the former yellow and orange palette of Pioneer Grain is peeking through in numerous places.

I had more hope for this monument, the final one to be found in my itinerary, as I had thought the site was a fairly small one so the places where a monument might be located were few. Unfortunately, I have similarly bad luck at finding it, succeeding only in finding another small sign erected by Ducks Unlimited. I know that I am in the right general location, but there is no sign of a monument. It is too bad that I get skunked on what might be the last site of this trip. I suppose that I should not be greedy. I have seen a lot of territory in these two days and found things that I did not expect to find.

From Dirty Lake, I decide against driving straight east to meet highway #16, going instead southward on highway #270 that will take me right through Rapid City. Before I reach the intersection of #270 and #24, a mile north of Rapid City, I pass the former site of Prairie College, now just a few scattered stones in a farm field. Prairie College is believed to be the first post-secondary educational institution in western Canada. It was intended to train Baptist ministers for service on the western agricultural frontier. It later merged with McKee Academy at Rapid City then relocated to Brandon in 1899 where it became Brandon College, the forerunner of today’s Brandon University. In commemoration of the significance of the Prairie College site to the educational history of Manitoba, several years ago historian Tom Mitchell gathered up a few of the stones (from the college’s stone foundation) and used them to build a cairn on the grounds of the University.

From Rapid City, it is a short four-mile drive (passing the Rapid City Cemetery, burial place for novelist F. P. Grove, on the north side) to highway #10, then sixteen miles straight south to Brandon. I need fuel for my car, and must make a decision about one last site. It is now 6:00 PM. Is the light still adequate for taking some photographs at a place on the east side of the city, in the middle of the Assiniboine River? After fueling up, I decide to have a look first-hand. What harm can come of it? Although I know the route to the site, I input the coordinates into my GPS and ask it to navigate there. I am surprised to see that I selects a different route than the one I would have chosen, a route that I did not know even exists. I headed out on the Trans-Canada Highway east of Brandon then turn south on the bypass highway around Brandon.

I cross the Assiniboine and turn east on what the GPS says is an extension of Victoria Avenue East. I can see only what looks like an impromptu parking lot of gravel, potholes, and grass. But I am curious. Maybe the GPS knows something that I do not. I continue driving, slaloming around large water-filled holes in the “road” and passing around a huge water hole whose depth I cannot estimate. I have to straddle deep ruts on which my little car would otherwise bottom-out on. This is crazy. I should turn back and go the other way. But I am determined to follow the trail where it leads. As long as it looks solid, I will continue. If it turns muddy, where I might get stuck, I will turn around, though there does not look like there is enough room to turn my car even if I wanted to. Finally, after three-quarters of a mile of white-knuckle driving, I arrive at an opening where vehicles have clearly parked in the past. Looking to the north, I see that it is exactly where I wanted to go. I see that the light on the object of my attention is absolutely perfect!

I climb out of the car, assemble the drone, and walk down to the edge of the river. There, gleaming with the orange evening light aimed directly at it, is a huge concrete pillar sticking out of the centre of the river. It is the most conspicuous remains of a railway bridge that once spanned the river at this spot. On each side of the river are massive concrete abutments that were also part of the bridge. Constructed in the early 20th century by the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, as part of a line running between Brandon and Brookdale, the line was abandoned before the rails had even been laid. Consequently, the bridge was never used and the steel spans were removed – and probably reused somewhere else – in the early 1920s. I have been here before, and flown the drone to get some aerial photos of the pillar, but it had been an overcast day with low, gray light. The trees alongside the river were also not fully in leaf so that photo was really not very impressive. This time, I wanted a photo that really showed the abandonment represented by this concrete structure. I got several such photos.

Re-packing the drone into the car, I take the other route that I had originally intended to use. It brings me back to the Brandon bypass highway, and thence to the Trans-Canada Highway. Two hours later, I drive into my driveway at home. It is about 9:00 PM and I have been on the road for about 36 hours in total, or about 20 hours in transit. It has been a productive trip. I took over 600 photos, some of which I plan to use in More Abandoned Manitoba, and others that will go onto the MHS website. Already, I am starting to plan my next road trip.

Rosedale Remembers, 1884-1984 by Rosedale Centennial Book Committee, 1984.

Obituary [Jeffrey Bruce Kirk], Neepawa Banner, 14 December 2012, page 16.

This page was prepared by Gordon Goldsborough.

Page revised: 5 January 2021

Historic Sites of Manitoba

This is a collection of historic sites in Manitoba compiled by the Manitoba Historical Society. The information is offered for historical interest only.

Browse lists of:

Museums/Archives | Buildings | Monuments | Cemeteries | Locations | OtherInclusion in this collection does not confer special status or protection. Official heritage designation may only come from municipal, provincial, or federal governments. Some sites are on private property and permission to visit must be secured from the owner.

Site information is provided by the Manitoba Historical Society as a free public service only for non-commercial purposes.

Send corrections and additions to this page

to the MHS Webmaster at webmaster@mhs.mb.ca.Help us keep history alive!