by Karen Nicholson

Historic Resources Branch, Province of Manitoba

|

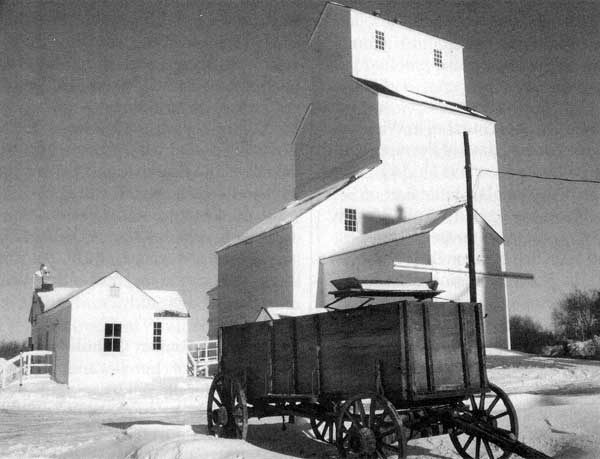

The most recent national historic site in Manitoba ranks among the largest in Canada’s repertoire, if only in the number of board feet (BFM) of lumber involved. The Inglis Elevator Row contains at least 500,000 BFM. When the elevators were erected in the 1920s, Burrows Lumber Company, the main supplier in the Parkland region, was turning out 5,000,000 to 7,000,000 BFM annually, most of it destined for railway ties and grain storage structures. The Canadian Northern Railway (today part of Canadian National Railways) alone constructed 3200 km of branch lines across the province between 1897 and 1930. About 2000 grain elevators were built in the same period. It is not surprising that the completion of these portions of Manitoba’s infrastructure coincided with the exhaustion of most of Manitoba’s old growth forests.

The Inglis elevators were deemed a National Historic Site because nowhere else in Canada, North America, or the world can one find another row of five traditional-style elevators. Over the last ten years, similar 20th century grain storage facilities have been demolished at an incredible rate. They have been replaced by even larger, cement and steel superstructures, which hold 100,000 to 300,000 bushels (2840 to 8540 tonnes) of prairie grain, as opposed to the 25,000 to 40,000 bushel (680 to 1088 tonnes) capacity of each of the grain elevators located at Inglis. Traditional-style elevators, albeit with more modern inner workings, were still being erected as late as the 1970s. What happened, then, to the grain industry in the past three decades to cause the explosion (or in this case, implosion!) in the number of elevator demolitions? To explain this, it is necessary to review the history of the grain trade in Western Canada, with the Inglis Elevators serving as a microcosm of the larger picture.

Wagons loaded with bags of grain, awaiting delivery to elevators in Brandon, circa 1888.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

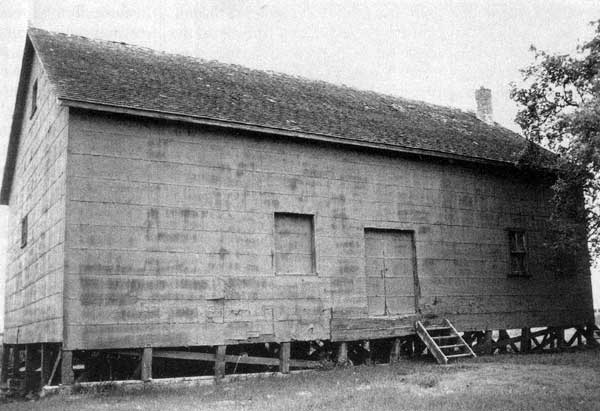

Brookdale flat warehouse, the only one remaining in Manitoba, 1981.

Source: Historic Resources Branch

Wheat was first grown in the prairie West (Red River Settlement) in 1815, but there was no market for it beyond the subsistence needs of the settlers. In 1870, Red Fife, hard spring wheat, was introduced to Red River via the United States. That same year a new technology, “the Lacroix purifier,” was developed. The purifier separated the bran from the wheat berry through use of a shaking screen and air currents, thus allowing the middling, or floury part of the wheat berry, to be refined rather than pulverized. This invention, along with the new chilled roller-milling process, made it possible to transform the hard spring wheat, which had proven itself suitable to prairie soils and climatic conditions, into flour for world markets. This development was an important factor in the settlement of western Canada.

But if Manitoba had an export product, it lacked transportation facilities to send it to market. By 1876, there was sufficient marketable surplus for the Steele Brothers Seed Company of Toronto to purchase 857.3 bushels (12.43 tonnes) of wheat in Winnipeg for seed in Ontario. The logistics of getting the wheat from west to east were daunting, involving a steamer to Fisher’s Landing, Minnesota, a rail trip to Duluth, another lake vessel to Sarnia and then a rail trip to Toronto. The creation of a network of railways, beginning with the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) line from St. Boniface to the American border in 1878, and then the CPR transcontinental railway, completed in 1886, became an essential part of development of the western wheat economy. Winnipeg became both a railway and grain trade centre. In the fall of 1883, the first grain destined for overseas was collected in Winnipeg and shipped by rail to Port Arthur and then to the waiting world. Now that a transportation route had been established, a grain-handling system needed to be created.

The CPR built its first grain terminal at the Lakehead (Thunder Bay today) in 1884. Until 1902, that railway company controlled all the terminal facilities at the Lakehead. The CPR had a monopoly on railway construction in Manitoba until 1888, after which time other companies began to build branch lines across the province, stimulating immigration, settlement, and grain production. Once the railways were in place, some means of handling the grain at the rural shipping points had to be designed. At first, the grain was brought to the railway in bags, and these were loaded by hand onto railway cars. Grain buyers next built flat warehouses beside the railway to house the bags of grain. Although these inefficient warehouses remained in use for more than two decades, only one of them still exists, in Brookdale, Manitoba.

The first larger grain storage unit, called an elevator, was constructed in Niverville. Its round shape was not a common design, however. The Ogilvie Milling Company built the first standard-style elevator, copied from an American design, at Gretna in 1881. This type utilized an endless cup conveyor, known as a leg, to raise the grain, which was dumped into a pit from the farmer’s wagon, to bins from which it could be more easily loaded by spouts and gravity into boxcars, placed alongside the building. The CPR commissioned grain buyers to build standard elevators, with 25,000 bushel (680 tonnes) capacities, along its lines. Other railways did the same and although some diversity in roof styles and shapes developed, over time these differences disappeared, as the elevators became sufficiently standardized to allow local labour to build and repair them. After 1900, it was difficult to discern the date of construction of an elevator by its shape, although its capacity might vary as high as 70,000 bushels (1,905 tonnes). The exceptions to this were the Ogilvie and Lake of the Woods Milling Company structures, which maintained a squarer design.

By 1890, individual grain buyers could no longer compete with companies like Ogilvie, and an amalgamation process began, resulting in the formation of line elevator companies such as the Northern and Dominion. These firms were known to take huge deductions from farmers for dockage (impurities in the grain), shrinkage (amounts lost in loading), and handling (transportation costs), and, although it was never proven, they were suspected of being in collusion to keep prices low. The 1900 Manitoba Grain Act laid out rules and regulations regarding dockage, weights, grades, and special binning, and forced the railways to continue to allow farmers the option to ship their grain directly from loading platforms. However, the farmer had to have enough grain to fill an entire car, which was difficult to secure, and to load the car in the amount of time allotted. This regulation remained in force until the Canada Grain Act of 1970.

Western Canadian farmers began to feel that railway and grain companies, and eastern manufacturers controlled their livelihood. Accusations abounded of price fixing at various elevator points. Elevator companies held a virtual monopoly on the local market and thus controlled the local price. If farmers could withhold their grain from the local market in the fall, or if they could ship it directly to the marketplace, they could increase their price. Farmers remained convinced that they needed greater control over the marketing aspect of their industry. They had tried farmer-owned elevators in the 1890s and while the presence of these had forced the line companies to be competitive, all but a few of them failed miserably. In 1906, through their local Grain Growers’ associations the farmers created the Grain Growers’ Grain Company, with a seat on the Winnipeg Grain Exchange. The new company would collectively sell their grain on the open market and pay them dividends. But because the new company owned no elevators, the grain still had to be stored in the existing line elevators.

The Grain Growers’ associations next lobbied the provincial governments to create a state-owned elevator system. In Manitoba, the Conservative administration of Rodmond Roblin reacted by creating the Manitoba Elevator Commission in 1910. While the government adopted the plan in theory, they did not institute it as advocated by the farmers’ lobby. Instead, the creation of a state-owned elevator line was administered by the Department of Public Works, which meant it was subject to bribery and corruption, especially since the Minister of Public Works at that time was Robert Rogers, a notoriously partisan politician who used the portfolio to reward friends of the party.

Of the approximately 700 elevators that existed in Manitoba in 1910, the Manitoba Elevator Commission purchased about one-quarter, mostly at higher prices than they were worth, from line elevator companies who took the opportunity to sell their least productive sites. The Commission built 12 new elevators as well as 29 more from the scavenged parts of other purchased structures. The Grain Growers’ associations criticized the government for creating a poor system and then running it badly. Nonetheless, the existence of the government elevators did provide some competition, as well as alternate storage space for the Grain Growers Grain Company.

This photo, taken in 1911, shows the three types of grain storage facilities in Niverville: the warehouse, the square-design Ogilvie elevator, and the round design of the first elevator in Manitoba.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

A row of elevators in the hamlet of Ninga, 1955. These have all been removed.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

In 1912, the whole line of government elevators was leased to the Grain Growers’ Grain Company, which had come to the realization that it needed its own elevator system. Although the Manitoba Elevator Commission had proven to be an abject lesson on how not to go into the grain storage business, it did provide the United Grain Growers (the new name for the Grain Growers’ Grain Company) with a ready-made elevator line. Under Manitoba-born Thomas Crerar, the United Grain Growers established an efficient elevator system, buying the best elevators in the leased line, dismantling some, and remodeling others. From having no elevators, in ten years the company rose to be the fourth largest elevator company in Canada.

This successful farmer-controlled company was about to face new competition, in the form of American businessmen from Chicago and Minneapolis who were expanding into western Canada along new railway branch lines. The Peavey family purchased the Northern Elevator line, as well as the Canadian Northern Railway’s grain terminal at Port Arthur. The Searle family bought and built elevators along Canadian Northern branch lines. By 1919, 35% of the elevators in Manitoba were American-owned. Today, the American company Cargill is a very active participant in the Canadian grain trade.

Farmers continued to consider the elevator companies and the railways to be the beneficiaries of their hard work. The fight over the freight rates charged by the CPR began in 1883 and a compromise was reached in 1897 when the CPR, in order to obtain a federal subsidy to build a railway line through the Crow’s Nest Pass into the mineral rich Kootenays in British Columbia, agreed to reduce its freight rates between the Lakehead and the West. This became known as the famous Crow Rate. The construction of two more transcontinental railways, the Grand Trunk Pacific and the Canadian Northern, provided competition, and thus further reductions in freight rates. In truth, however, Western Canada could not support these extra railways. The two lines were taken over by the federal government, and amalgamated to become Canadian National Railways in 1921. The Crow Rate, suspended during the First World War, was reinstated in 1922 and enshrined by federal statute in 1925.

In that same time period, western farmers began to turn to the co-operative style of grain marketing, developing wheat pools in each prairie province. Under this co-operative system, members’ wheat was pooled to create a large enough stock for the Central Selling Agency to sell directly on the world market. The first co-operative elevator in Manitoba was built in Roblin, in 1925. The idea of removing the middleman from the grain trade was sound enough, but the Great Depression of the 1930s brought the pools to their knees. Saved from bankruptcy by a bailout from the federal and provincial governments, the wheat pools were reduced to a co-operative elevator system, with the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) given responsibility for world marketing of the Canadian wheat crop. The individual co-operative elevator associations eventually united to form Manitoba Pool Elevators, which by the 1970s became the largest grain-handling company in Manitoba. In recent years, Alberta Pool and Manitoba Pool have amalgamated with United Grain Growers to form Agricore United.

In 1935, the establishment of the Canadian Wheat Board created the final block in the Canadian grain-handling system, and there would be little change for the next fifty years. The Second World War and the postwar era brought prosperity to the agricultural sector. It marked a period when mechanization and chemicals revolutionized farm production, while the grain-handling system remained in the horse and buggy age.

There were several factors that contributed to this stagnation, the most important being the grain-marketing policies of the CWB. In order to stabilize wheat prices, grain stocks were held off the market. Crops were good in this period and farmers took their grain to the elevator companies, who were paid a grain-handling fee by the CWB. The fee, however, was too low to finance the expenditure of modernizing the elevators. Instead the grain companies began to rely on storage costs for their profits. In the 1950s, the Canadian government started to reimburse the CWB for storage costs for wheat stocks, transforming storage costs into a “cash cow” for the grain-handling industry. It was in this period that huge balloon annexes were added to elevators, to create more storage space. With full elevators and yearly storage payments, there was no incentive to the grain companies to close their antiquated elevators, or to consolidate groups of smaller facilities for a more centralized efficient structure where multi-car shipping could be utilized. If a company closed an elevator at one point, its management believed that farmers would not undertake to follow it down the road to a better elevator. Farmers, it contended, would just change their allegiance to another company still buying at the first point.

The deadlock could only be broken by changing the shipping patterns and rates, making it more profitable for the farmer to haul to a larger facility where multi-car shipping was available, and making it unprofitable for the elevator companies to keep their structures filled for storage costs. It was the CWB that controlled the allocation of grain cars, not the grain companies. Often the CWB was unaware that an elevator was “plugged” for years, as the grain company silently continued to remit bills for storage costs. More importantly, the existence of the Crow’s Nest Rate allowed the railway company no flexibility in the freight rate, and therefore provided no incentive to initiate multi-car shipments from larger terminals.

To reduce the number of elevators, it was first necessary to reduce the number of shipping points and this could best be accomplished by rail abandonment.

Rail abandonment were “dirty words” in farm communities. First of all, railway and elevator companies paid taxes to the rural municipalities. If these facilities disappeared there was no new tax base to take their place on the tax rolls. Secondly, farmers believed railways owed them. Hadn’t the rail companies all been given large land grants to subsidize the building of their lines? Thirdly, most farm communities viewed the loss of their railway as the beginning of the end for their village. In fact, in many communities the railway outlasted the centralization of educational, medical, postal, and commercial activities to larger centres.

The Inglis elevators as they looked before the restoration project began, in 1994.

Source: Historic Resources Branch

Demolition of an elevator in Dominion City, in 1999.

Source: John Lehr

The inadequacies of outdated elevator and railway equipment were highlighted in the 1960s when the CWB negotiated the first large grain sales to the USSR and China. The Canadian government undertook various studies and programs, such as subsidizing uneconomical branch lines, to patch the system. By the early 1970s, there was a total breakdown in grain transportation when the railways refused to purchase modern grain hopper cars without a restructuring of freight rates to make the expenditure profitable. The government’s response was to purchase new hopper cars itself. It was obvious to everyone in the grain industry that rail abandonment and freight rates were tied together and some drastic action was required to fix the problem. When the heads of United Grain Growers and the Pools finally spoke out in favour of removing the Crow Rate, the stalemate was broken. In 1984, the Western Grain Transportation Act cancelled the Crow Rate. The effect was equivalent to opening the floodgates. Railway lines were abandoned, and the elevators along them closed in dizzying fashion. Amalgamation of grain companies was followed by consolidation of grain-buying services in the larger, newer structures. Gradually even these were deemed outmoded and the grain companies began to erect gigantic inland terminals at central points. The discarded structures were mostly demolished by implosion, but many were also painstakingly dismantled for the vast amounts of lumber they contained.

The new computerized grain storage facilities, which hold at least 200,000 bushels (5680 tonnes) of grain, were erected well beyond town limits and designed to serve an eighty-kilometre radius. The producer bore the cost of the increased delivery costs, further fueling a growing trucking industry. Grain transport trucks, carrying 800 to 1400 bushels (11.6 to 20.3 tonnes) of grain per load, now traverse the distance once covered by railways. The impact of this increased highway traffic has resulted in a marked rise in maintenance costs of market roads.

By 1988, the wholesale disappearance of the elevators, often described as “prairie sentinels,” was so threatening to rural landscapes that the governments of all three prairie provinces received appeals from concerned citizens to save the familiar prairie icons. The Historic Resources Branch of the Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Recreation Department responded by undertaking a background study and an inventory of grain elevators in our province. Of the 220 traditional-style elevators it inventoried in 1992, few are still standing today. The background study, prepared on contract by Dr. John Everitt of Brandon University, served as a guide for evaluating the historical significance of each of the elevators. When the evaluation process was completed, it was no surprise that five elevators standing along an about-to-be abandoned CPR branch line at Inglis rated so high that the Historic Resources Branch believed they deserved recognition as a National Historic Site, as well as a Provincial Heritage Site. Dr. Everitt had maintained from the outset that the Inglis elevators were a treasure.

The history of the five elevators located at Inglis reflects the changes in the grain-buying industry over the last century. Paterson & Son built the most northerly elevator along the new CPR branch line in 1922. An annex was added to this elevator in 1949. The smallest elevator, built in 1922, by the Matheson-Lindsay elevator company, was sold in 1928 to the Province Elevator Company, later known as the Reliance Elevator Company. Reliance built a second, larger elevator immediately beside the old one in 1940. These two elevators, once connected and operated from one office, were sold to Manitoba Pool in 1952. In 1971, during a friendly exchange, involving United Grain Growers, Pool, and Paterson, to consolidate shipping points, Pool sold its two Inglis elevators to United.

The fourth elevator was constructed by the Northern Elevator Company in 1922, and along with the entire Northern Elevator line was amalgamated into the American-owned National Grain in 1940. This company was taken over by Cargill Grain in 1974. They later sold or traded their Inglis elevator to Paterson. The southernmost elevator was built in 1925 by United Grain Growers to replace an earlier one destroyed by fire in 1922. Very little major renovation or modernization took place on any of the structures over the 70 years of their commercial existence, but in the same period, the number of grain companies operating in Manitoba shrunk from 67 to eight. In Inglis, this consolidation left five grain-buying facilities in the hands of two major companies.

In the summer of 1994, a speaker at a tourism forum in Russell, aware of the Historic Resources Branch’s elevator study, mentioned the significance of the Inglis elevators. Local Inglis resident Marcia Rowat went home from the forum with a new impression of the huge structures behind her house. She gathered around her a group of people who were interested in saving the elevators, forming the Inglis Area Heritage Committee (IAHC). At the end of the harvest season in fall 1995, the Inglis elevators were closed, along with the Russell-Inglis branch line. In February 1996, the Inglis Elevator Row was designated a National Historical Site. Provincial Heritage Site designation followed in 1999. With funding from the provincial government, the engineering firm of Roberts, Sloane & Associates Inc. was hired to complete a physical assessment of the site.

Marcia Rowat and Dr. John Everitt unveil the Manitoba Heritage Council plaque at Inglis in 2002.

Source: Historic Resources Branch

The assessment showed that the structures, including the one “leaning tower of grain,” could be restored at an estimated cost of over two million dollars. The community, overwhelmed by the task of finding the financial resources to accomplish the “unthinkable,” might have given up without Ms. Rowat’s determination, and the help of the federal government’s Canadian Heritage Department, which was able to provide the group with a Cost-Sharing Agreement for one million dollars. The Inglis Area Heritage Committee, with help from government staff, worked hard to locate matching funds. N. M. Paterson and Sons and United Grain Growers, who between them owned the five elevators, donated the structures, as well as financial resources equivalent to the cost of demolishing them. This money has been held in trust since the beginning, lest the project ultimately failed. Over the past seven years, the provincial government has provided over $370,000 in building and heritage grants, with the potential for more each funding year. The Thomas Sill Foundation and other corporations and foundations have been generous in their support. Recently, the Murphy Foundation donated $100,000 to help with the restoration of an elevator that once belonged to Reliance Grain, which was owned by the Murphy family. And then there were the immeasurable contributions of the many local residents who generously dedicated their time and talents to fundraising.

Inglis residents were told in 1994 that the full potential of the Elevator Row would not be realized for twenty years. Nearly ten years later, the elevator restoration project is well past the halfway point. The Committee is beginning to think it might be able to spend the money put in trust for demolition! One elevator, along with the manager’s office, has been totally restored. Because this serves as an interpretive centre and gift shop, visitors can now do more than survey the outside majesty of the looming structures. During its first season of operation in summer 2002, over 2000 people, from destinations as far away as Ukraine, visited the site. The visitation hours at the site are still limited but these will be expanded as more of the structures are completed, and the Committee begins to focus greater attention on operating the site, as opposed to restoring it.

The restored Paterson Elevator, as it looked in winter 2001.

Source: Historic Resources Branch

Evidence of the economic impact of the National Historic Site is starting to be visible. Most of the restoration money has been spent within the region, and local young people have been hired for summer jobs. Inglis residents have taken the site to their hearts and everything in the little hamlet seems to have been spruced up to reflect the pride the local people take in their unique skyscrapers. Ironically, the elevators provide more employment today than they did as grain-buying facilities.

The Inglis elevators outlived their contemporaries because they were located along a railway line that was marked for closure over thirty years ago. The elevator companies were reluctant to spend any money to modernize the structures, but found them convenient storage bins until the grain-handling system entered the modern age. To farmers, who bore the economic brunt of the antiquated system, the elevators were not shrines to commercial progress, but rather places that frustrated their efforts to reap the economic benefits of their labour. It was not surprising then, that many agriculturists in the Inglis area, when first apprised of the project to save the elevators, advocated tearing them down. It has taken time for them to see that others would value something they did not.

Inglis is not located on a major tourism route, but it may be responsible for transforming the Inglis-Russell region into a tourist destination. And why not? If tourists will drive and hike into the interior of British Columbia to visit the restored mining town of Barkerville because. of its unique- ness, then why not Inglis, whose elevator row is equally unique? As one rounds the curve on the three-kilometer drive off PTH#83 into Inglis, the sudden appearance of the strange tall structures, glistening white in the sunlight and reaching for the sky, will take your breath away, even if you aren’t a farmer’s daughter!

For more information on the Inglis Elevators, or to make .a donation towards preserving and interpreting this important part of Manitoba’s past, please contact the Inglis Grain Elevators National Historic Site, Box 81, Inglis, Manitoba ROJ OXO; telephone 204-564-2243; e-mail iahc@mts.net.

Earl, Paul. “Good Intentions on the Road to Perdition.” Paper presented at the Manitoba History Conference, 9 May 1998.

Earl, Paul. Mac Runciman. A Life in the Grain Trade. University of Manitoba Press. 2000.

Everitt, John. “A Study of Grain Elevators in Manitoba,” Unpublished Report. Historic Resources Branch, Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Recreation, 1992.

Friesen, Gerald. The Canadian Prairies: A History. University of Toronto Press. 1984.

IAHC. Inglis Elevators National Historic Site: Storing a Century of Canadian Agriculture History. December 2002.

IAHC. On Track, The Official Newsletter of the Inglis Elevators National Historic Site. 1998-2002 issues.

See also:

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Inglis Grain Elevators National Historic Site (Inglis, RM of Riding Mountain West)

Page revised: 18 March 2018