by Harry Gutkin and Mildred Gutkin

|

Manitoba was the first province in Canada to grant women the right to vote: this year, 1996, marks the eightieth anniversary of this signal advance in the ongoing struggle for women’s rights. This article tells the story of the achievement, with a particular focus on some of the women who led the suffrage movement in Manitoba. A number of these women play a prominent part as well in the most recent book by Mildred and Harry Gutkin, Profiles in Dissent: The Shaping of Radical Thought in the Canadian West.

On 27 January 1914, a large delegation of both men and women appeared before the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba, once again to present the case for granting women the right to vote in provincial elections. Included in the group were representatives of the Political Equality League, the Grain Growers’ Association, the Young Women’s Christian Association, the Trades and Labor Council, the Icelandic Women’s Suffrage Association, the Canadian Women’s Press Club, and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Dr. Mary Crawford, the President of the University Women’s Club and of the Political Equality League, introduced the five speakers, two women and three men, and the last to address the lawmakers was Mrs. Nellie McClung. Then rivalling Ralph Connor as Manitoba’s most popular writer, Mrs. McClung made her point with sharp lucidity. The delegation had come, she said, not to beg for a favour but to obtain simple justice. “Have we not the brains to think? Hands to work? Hearts to feel? And lives to live?” she demanded. “Do we not bear our part in citizenship? Do we not help build the Empire? Give us our due!”

The Conservative premier, Sir Rodmond Roblin, rejected Mrs. McClung’s demand absolutely. “Most women,” he told the petitioners, “don’t want the vote.” In Colorado, he informed them, where women could vote, “they shrank from the polls as from a pestilence.” Woman suffrage, he said, “would be a retrograde movement ... it will break up the home ... it will throw the children into the arms of servant girls.” Then he added, gallantly, that there was “nothing wrong with a society that produced such attractive, pure, and noble ladies” as these now before him, but “the mother that is worthy of the name and of the good affection of a good man has a hundredfold more influence in shaping public opinion around her dinner table than she would have in the market place, hurling her eloquent phrases to the multitude.”

Roblin’s flowery courtesies expressed the received attitude of his time and his social group towards the tender sex, simultaneously idealized and subjugated. He loved his mother, he said, and for her sweet sake he revered all women. “Gentle women,” he described the ladies, “queen of the home, set apart by your great function of motherhood ... Women are superior to men, now and always.” Nice women did not want to vote, the common argument ran, and since women exercised so important an influence for good, they must be sheltered from the world and its corruption.

Absolutely not, the suffragist movement insisted; women must be given the right to act in that world, to remake that world for future generations. They were constantly rebuked: was not woman’s place in the home with her children? “Yes,” retorted Nellie McClung to one opponent, “but it’s also in the world those children must enter!” The feminists of the early twentieth century envisioned a world in which the nurturing values of home and fireside would be paramount, putting an end to war and to the exploitation of the weak by the powerful.

About the women confronting him at the legislature, Roblin’s perceptions were quite accurate in one respect. These were no proletarian toilers, intruding into the deliberations of their betters. Such presumption, he implied, would be unthinkable: he was afraid, he said, that “my friend Mr. Rigg”—Richard Rigg, the labour activist—“might shortly come to us for the extension of the franchise to servant girls, on the plea that servant girls have as good a right to vote as any other class of women.” In the rank and file of the suffrage movement were to be found the wives and daughters of successful men, newly leisured and eager to assert themselves outside the narrow domestic sphere.

Nellie McClung herself, as her writing and lecturing career developed, was able to entrust much of the household drudgery to a succession of immigrant servant-girls, and made one of them the heroine of a novel.

In the growing torrent of dissent that was inexorably altering Canadian society, even before the turn of the century, one irresistible tributary stream was the demand of educated, well-informed women for change, primarily in the franchise legislation and the laws on property and dower rights, as well as in the provisions for the health and well-being of the community. With some degree of economic security, and in many cases some access to men in positions of power, they demanded legal recognition of their equal worth. In Manitoba, significantly enough, the leaders of the woman suffrage movement, with some exceptions, stemmed originally from the self-confident, well-established British background of southern Ontario, a society that took for granted intellectual accomplishment and community leadership.

Two decades earlier, in 1882, twenty-one-year-old Cora Hind had arrived in Winnipeg from Ontario, to carve out a career for herself in journalism. Her close friends were two women doctors, also originally from Ontario, the mother-and-daughter pair of Amelia and Lillian Yeomans; Amelia’s brother, William Dawson, became President of the Royal Society of Canada. The Beynon sisters, Lillian and Francis, were born in Kings, Ontario; Lillian earned a university degree, and both taught school before becoming influential journalists. Dr. Mary Crawford was the daughter of a Scottish schoolmistress who had emigrated to become the principal of an Ottawa ladies’ college. Nellie McClung, on the other hand, grew up on a remote Manitoba farm, of Scottish-Irish stock, but her immigrant parents instilled in their offspring the absolute determination to become something more than shop assistants or farm labourers.

When Manitoba entered Confederation in 1870, the right to vote in provincial elections was assigned to male householders; that is, to “the master or chief of a household; one who keeps house with his family,” if he either owned his home or occupied “a separate maintenance and table enjoyed by himself and his dependents, distinct from other householders.” The following year, the voter, identified specifically as a “male person,” was re-defined as a “rate-payer,” required to have owned property valued at $100 or more for a year prior to the election, or to have paid a yearly rent of at least $20. A single woman, under certain conditions, could be a property-owner and a rate-payer; once married, however, her holdings generally passed to her husband, and if widowed or separated, she had no “dower rights,” no legal claim on any part of her husband’s estate. In any case, whether she did or did not own property, no woman could vote. The federal Election Act, indeed, decreed flatly that “no woman, idiot, lunatic, or criminal shall vote.”

In the economy of western Canada, however, women’s role differed markedly from the situation in the settled Ontario townships, where the conventional structures of patriarchal society were the norm, assigning women to dependence on men. Farm women worked side by side with their men in the back-breaking task of establishing a homestead, and the urban centres tended to attract some strong-willed young women, already declaring their independence from their families, and as determined as their brothers to improve their own prospects. Prairie women were an assertive presence in the pioneer economy, prominent in farm organizations such as the Grain Growers’ Association, and the farm groups could generally be relied on to throw their support behind the suffrage movement, with its component demand for the reform of property laws. In the Canadian West, as in the American, women achieved the franchise ahead of their sisters in the conservative East.

In Manitoba, a partial break came in 1887, when female rate-payers were granted permission to vote in municipal elections; and in 1890 they were declared eligible to vote in school elections and also to serve as school trustees. Eastern public opinion seems to have been aghast at the recklessness of the uncouth frontier in making this move, and from pulpits and editorial pages alarmed opinion-makers predicted catastrophe: marriage could not survive if a man could not be certain what his wife did in the secrecy of the polling booth, or worse, if she openly defied his judgment. If she opposed him, her vote would cancel his, and if she concurred, what was the point of her voting at all? In any case, nice women did not want to vote.

Notwithstanding Manitoba’s radical concession, the suffrage battle there had barely begun. In 1888 the property qualification for provincial elections had been removed from the male franchise, permitting all adult men to vote, but excluding women, as before. Gathering strength, the campaign to enfranchise women and to establish their economic rights would continue for thirty years longer, led by a number of political-minded women.

Cora Hind arrived in Winnipeg with her aunt, Alice Hind, in August 1882, eager for a writing career. She had come with a letter of introduction from her uncle George Hind to W. F. Luxton, the editor of the Manitoba Free Press, and Luxton received her cordially. As for her writing ambitions, however, he advised her most kindly that newspaper work, with its late hours and its questionable characters, was not for a well-bred young lady; she would have to try some other occupation. Some months later, however, he did publish a small sketch—anonymously, without the female signature. Then, some family business brought the young woman to the law offices of Archibald and Howell, and, hearing her tale of frustration, Mr. Howell suggested that she qualify as a “typewriter,” learning how to operate the recently introduced office device. He had been down in the States, he said, and had seen quite a few girls at that employment. The invention was to provide a new career possibility for women.

E. Cora Hind

Source: Archives of Manitoba

It took Hind several weeks, pounding away by herself on a rented machine, to work up speed in the two-finger style she was to retain all her life, and then she was ready to make her entry into the world of business. There were few if any other “type-writers” in the Winnipeg of the 1880s, and she landed a position with the law firm of Macdonald, Tupper, Tupper, and Dexter, at six dollars a week, her duties carefully specified. The office manager took shorthand dictation from the lawyers, transcribed the copy in his copperplate hand, and turned it over to the new female employee, to be reproduced on the newfangled contraption. It pleased Hind to recall, years later, that the first typed brief used in the Winnipeg law courts was her work, and lawyers from many offices came to observe this innovation in legal procedures.

In 1893, Hind took the bold step of establishing her own independent “typewriting bureau,” the first public stenographic service west of the Great Lakes. The move brought her close to the centre of the burgeoning city’s hurly-burly. She worked, she said in a 1932 interview, “for all classes and conditions of men, and from every one of them I learned something ... British diplomats on their way to and from China, prospectors from the gold region of northern Ontario ... circus managers and church dignitaries.” Once, she said, for “a gentleman passing through Winnipeg, who had little English,” she wrote a proposal of marriage to his lady-love in California, who had no Spanish—“the most florid piece of literature I have ever produced, but the gentleman said sadly it was very cold, but he supposed it would have to do.”

Making some invaluable contacts, Hind became secretary of the Manitoba Dairy Association, and began reporting, as she said, on the side, specializing in farm affairs, and from time to time submitting articles to various publications. In those early days, she remembered, her work would sometimes appear signed by “E. C. Hind,” because editors thought it judicious to conceal her female identity, but she would indignantly insist on her proper signature, E. Cora Hind, because, she said, she owed it to other women writers. Her first report in the Free Press of a farmers’ convention was published in 1893, but it was not until 1901, when John W. Dafoe became editor, that she was hired as a permanent member of the staff.

With her own by-line on the newspaper, E. Cora Hind became a familiar figure in the rural areas, profoundly aware of farmers’ problems in financing their operations and in marketing their crops. She developed into an infallible judge of the annual western Canadian wheat crop, often to the irritation of the speculators attempting to manipulate the market. Most particularly, the newspaperwoman from the city observed with vivid compassion the hardships of farm life on the prairies—the unending physical toil, the isolation through parching summers and long, snow-swept winters, the scarcity of most of the amenities of civilization—and her indignation grew at the inequities in the situation of farm women, deprived by law of any claim on the property they helped to develop.

Meanwhile, Alice Hind had joined the Winnipeg branch of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and her niece had followed suit. That much-lampooned society of pious ladies inveighing against “Demon Rum” had been founded in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1874, in response to a very real social problem. Liquor, its production and sale, was a thriving industry, virtually unregulated by legislation, and alcoholism threatened to destroy the promise of the new world. The determined ladies who forced their way into the raucous saloons, singing hymns and handing out pamphlets, were hard to combat, and ridicule was the best weapon, but for the women and children of the poor, whose very food and lodging were being drained away by the seductive conviviality of the men-only bars, chronic drunkenness brought tragedy, all the attendant evils of destitution, sickness, and domestic violence.

Essentially, the WCTU was committed to the traditional womanly values of home and motherhood, but in campaigning against alcoholism, it was led into the battle for reform in many related areas. Child welfare, moral education, prison welfare, peace and world community: these were some of the concerns in which the WCTU was active; and particularly in the West its branches attracted as members some of the staunchest advocates of women’s suffrage.

In 1883, the year that the WCTU came to Toronto, a branch was also organized in Brandon, Manitoba. Within ten years a large chapter was active in Winnipeg, and a number of rural branches became members of the Provincial Union. The 1893 provincial convention unanimously endorsed a suffrage resolution, “that we will never cease our efforts until women stand on an equality with men, and have a right to help in forming the laws which govern them both.”

In the Winnipeg branch, Cora Hind began typing speeches for WCTU members, and composed some of them herself, on the imperative social reforms. She became treasurer of the organization, and addressed Temperance Union conventions, repeatedly urging the members to reach out to the wider social issues which their battle against liquor entailed. Here also she met Amelia and Lillian Yeomans, and the two pioneer woman physicians became fast friends of the newspaperwoman, frequent visitors in her home on McDermot Avenue.

Older than Cora Hind by about fifteen years, Amelia LeSueur had been born and educated in Quebec, and at eighteen had married Dr. Augustus A. Yeomans. Two daughters were born, and the family lived in Ontario for a time, then followed Dr. Augustus to the United States, where he served as an army surgeon in the American Civil War. In 1879, a year after Augustus died, the older daughter, Lillian, elected to pursue a career in medicine.

Dr. Amelia Yeomans

Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index

Women were still not welcome in Canadian medical colleges: it was not until 1880 that Augusta Stowe was allowed to enter the Toronto School of Medicine, the first female student in a Canadian medical college. Lillian was accepted at the University of Michigan medical school, and the next year her mother enrolled there as well. Lillian graduated in 1882, applied for and obtained registration with the Manitoba College of Physicians and Surgeons, and set up practice in Winnipeg. Her discreet announcement in the Free Press informed the public that she was offering services in “Midwifery and Diseases of Women and Children.” It also prompted one writer for the paper to boast of the admirable “lady physician” that made this town “the equal of any place in the world.” Amelia obtained her degree in 1883, and joined her daughter in Winnipeg, to be registered with the College of Physicians and begin practice there a year or two later. Charlotte, the second daughter, qualified as a nurse, and came in 1890.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Winnipeg had mushroomed into a bulging outpost of some forty-two thousand people, with an unsavoury reputation as one of Canada’s wickedest cities. In the over-crowded North End, inadequate housing and poor sewage made disease endemic, and poverty fostered crime of every sort. Thousands of unattached men flocked through the city on their way to homesteads farther west, or remained in the city to try their luck: married immigrants having left families behind, bold young stalwarts glad to escape the restraints of traditional societies, farm-workers at harvest-time answering the call for hands to garner the bountiful prairie grain. On Annabella and MacFarlane Streets, just north of the CPR tracks and within walking distance of the station, a red-light district flourished, its brothels providing the time-honoured employment for dozens of women, its business winked at by the authorities.

The two women practitioners were frequently called to the jails, where the rowdiest of the ravaged prostitutes were confined, and where beaten and homeless women found a shelter of last resort, male and female prisoners housed together in the same wards. As the Yeomans’s indignation grew, they invited their friend Cora Hind to accompany them on their rounds, and to write about what she had seen. She insisted that the newspaper publish a full report, sparing no details:

The cells are totally devoid of light or ventilation, except such as may be had through the doors ... No sleeping accommodation is provided, and no bedding is allowed, except that blankets are sometimes given to the women ... The wards are infested with vermin, drugs, lice, and cockroaches ... Some of the most abandoned are afflicted with syphilis and other loathsome diseases, and healthy prisoners are exposed to the danger of becoming similarly affected. The men and women are obliged to use the same towels, closets, etc., so that those who are healthy can scarcely escape the consequences.

There was a storm of protest against the indecency of discussing such things in public, an even more shocking impropriety because it came from a woman’s pen, but voices were also raised against the inhuman conditions she had revealed. The WCTU campaigned to establish a home for “these fallen sisters of ours,” a place where they could be cared for after their release from jail, and distributed a pamphlet for women by Dr. Yeomans on the dangers of social diseases in the big city. Both the writer and the sponsoring group were roundly denounced for this assault on the sheltered innocence of womanhood and, Cora Hind remembered, fathers forbade their wives and daughters to attend the troublesome WCTU. Forced prostitution, the so-called “white slave trade,” became the subject of a widespread public outcry, and the authorities were finally compelled to curb the most flagrant of the brothels.

A devout Christian, Dr. Yeomans argued that in the same way that many women had assisted Christ in his ministry on earth, so women must be allowed to join fully in the task of setting society on the path of righteousness; and to that end they must be given the right to vote. Woman, it was promised in the third chapter of Genesis, would “bruise the head of the serpent,” leading the battle against sin in the world, and for Dr. Yeomans the head of the serpent was primarily alcohol, destructive of body and soul. In 1891, the Manitoba WCTU officially endorsed the suffrage movement as a support to the temperance cause, although adding cautiously, out of deference to the more conservative members of the sisterhood, that the Union was not to be considered a female rights association, and members need not necessarily approve of votes for women.

Nevertheless, two years later the Temperance Union sponsored a mock parliament at the Bijou Theatre in Winnipeg, to debate the subject of the franchise, with Cora Hind and about twenty other Temperance ladies from the city and the surrounding towns playing the parts of the sitting members of the current legislature. Amelia Yeomans, in the role of the provincial premier, argued earnestly that women were the protectors of society’s moral values, that if they were able to vote, respect for them would increase, their influence would be enhanced, and the Empire itself would benefit. A woman’s responsibilities were those of a mature adult, she protested, yet her social and political powers were those of a child. Warming to her task, she declared passionately that “A woman is a rational, independent organism endowed by the Creator with certain natural rights which no one may in-fringe without wrong-doing”; and the audience responded enthusiastically to the suffragists’ cause.

Righteously, the Free Press reported that “wiser and better men left the hall than entered it during the early part of the evening.” The play netted the WCTU $108.20, which was ear-marked for further educational purposes. Within a few days, a suffrage petition circulated by the WCTU had collected the signatures of an estimated five thousand men and women, and the Free Press editor predicted that the issue would now be taken to the provincial legislature.

In April, a supportive MLA, David McNaught, presented the ladies’ petition at a legislative session, arguing—with a certain levity, perhaps—that “man was made out of dust, but woman out of a better material, Adam’s rib,” and therefore women would prove better judges of politicians’ probity. A woman suffrage bill was suggested, but it reached the floor only in the form of another resolution, which drew some vocal support, but was defeated when a vote was taken. The following February, in 1894, the petition was presented to the House once again, with the addition of the names of some two thousand women over the age of twenty-one. This time the first actual women’s suffrage bill in the Manitoba Legislature was introduced by MLA Robert Ironside and received first reading, and an eager contingent of suffragists crowded the visitors’ gallery the next day for the expected second reading. Their hopes were dashed. The sponsor of the measure withdrew his support with a curt announcement that the bill was “Not printed,” and nothing further came of this attempt.

Not all women’s organizations were ready to take up the suffrage cause. In 1894, the National Council of Women, at a convention in Ottawa, officially dissociated itself from the franchise movement, and the suffragist members withdrew to form their own national organization. In Manitoba, at the end of a WCTU meeting, Amelia Yeomans announced the formation of an important new society, and a number of women stayed on to hear more. Miss E. Cora Hind moved the resolution founding the Equal Franchise Association, or the Equal Suffrage Club, as it was also called, and Dr. Amelia Yeomans was elected president. The first English-speaking suffrage society in western Canada, its declared objectives were to study the social and political economy in the light of Christian ethics and to develop and distribute suffrage material. Its motto was “Peace on Earth, Goodwill to Men,” but with a proviso:

a peace founded on justice and righteousness, and a good will shown by the consecration of all our talents and powers to serve our communities and the nation, of which disenfranchised women form numerically half the adult population.

Its by-laws stipulated that membership on the executive committee was to be limited to women only.

In 1903, Winnipeg’s small corps of professional women was increased when Dr. Mary Crawford arrived to set up her medical practice, specializing in diseases of children. Born in Lancashire, England, in 1876, she had displayed an early interest in both music and medicine, neither of which her mother considered a suitable occupation for a lady, and instead had taken a certificate in kindergarten teaching. After her mother’s death, she had begun medical studies, training at Trinity Medical College, Toronto, and at the West Philadelphia Hospital for Women. Her practice in Winnipeg was chiefly in the immigrant North End; she became immersed in the social problems she encountered there, and volunteered her services at James Woodsworth’s Stella Mission. She became a part-time inspector for the Winnipeg Public School Board in 1909; she succeeded Amelia Yeomans as President of the WCTU; she joined the University Women’s Club and was elected President; and she joined the campaign for the franchise.

In the mid 1900s, Charlotte Yeomans left Winnipeg for Calgary, and her mother and sister followed. The Suffrage Club dwindled inconclusively in the next few years, and the Temperance Union as well slowly faded from prominence.

Among the immigrants pouring into the young province from all over Europe, one group of people had made its own, virtually independent bid for the recognition of women’s right to the franchise. An Icelandic community had begun to take shape around the southern shores of Lake Winnipeg in the 1870s, only a few years after the West entered Confederation, and in short order its Women’s Societies and Ladies’ Aid groups played a leading role in Icelandic community activities. In 1890, at a meeting in Argyle, Manitoba, a second district where Icelanders congregated, three speakers argued for the extension of the franchise, and the entire audience joined in the debate that followed. The outstanding instrument in the suffrage campaign was the Icelandic-language monthly, Freyja, meaning “Woman,” published between 1898 and 1910 by Sigfus and Margret Benedictsson.

Margret Benedictsson, circa 1905

Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index

The Benedictssons opened a print shop and publishing house in Selkirk, Manitoba, then moved the business to Winnipeg. Their journal undertook to pursue “matters pertaining to the progress and rights of women,” and to “support prohibition and anything that leads to the betterment of social conditions.” Freyja reprinted articles from the Icelandic and the American and European press on the activities of women’s groups, encouraging its readers to take up the cause of equal rights for women. Marriage, Margret Benedictsson deeply believed, should be seen as an equal partnership between the breadwinner and the home-maker, and she was forthright in her insistence that the remedy of divorce must be freely available to end an unhappy union. She also argued that women must have access to the wider spheres of public and professional life, and she proposed that the conventional Ladies’ Aid expand its function to provide insurance benefits for its members, a means to further women’s independence.

By 1908, an Icelandic suffrage group called “Sigurvon,” or “Hope of Victory,” was functioning in Argyle, and several other Icelandic communities followed suit. A number of suffrage petitions were subsequently presented to the Manitoba legislature, “praying for the passing of an act to enfranchise all women, whether married, widowed or spinster, on the same basis as men.” Also in 1908, Margret Benedictsson founded the Icelandic Suffrage Association in Winnipeg, hailed by Freyja as the first in America, and affiliated it with both the Canada Suffrage Association and the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. As for local English-speaking women’s rights organizations, the Icelandic and the Winnipeg branches of the Women’s Canadian Temperance Union combined in 1902 and again in 1914 to petition the provincial government for the franchise, but there was not a great deal of cooperation or exchange between the two groups. Margret Benedictsson left her husband in 1910, taking her three children to the United States, and Freyja ceased publication.

The Anglophone suffrage movement gained momentum slowly in the first decade of the twentieth century. Reconsidering its earlier decision, the National Council of Women, in 1904, approved a standing committee on citizenship and women’s suffrage, although full endorsement did not come until the 1910 convention. Women rate-payers still retained the right that had been granted to them in 1887, to vote on municipal matters, and in 1906 one Manitoba town demonstrated how effective that power could be. The Roblin government was rudely jarred when Carman exercised its local option to ban liquor from the town, with the women’s vote tipping the balance. Under pressure from the liquor interests, it would seem, to prevent another such occurrence, the legislators rescinded women’s right to vote, only to be met with so intense a barrage of protest that at the next session they restored the privilege: an unintentional error, government sources blandly declared.

By the early 1900s, a sizable number of women across Canada had made a place for themselves in newspaper work, and through the printed page these women acquired an audience they had not had before. John Dafoe hired Lillian Beynon in 1907 as women’s columnist for the Weekly Free Press and Prairie Farmer, with considerable freedom to decide how to use her allotted space. Four years later, George Chipman invited Francis Beynon to become woman’s editor of the Grain Growers’ Guide.

The family of James and Rebecca Beynon and their three daughters and four sons had moved to the Hartney district of Manitoba from Ontario in 1889, when Francis was five years old and Lillian was fifteen. Strict Methodists, the Beynon parents organized church services and Sunday school classes, and Rebecca played a dominant role in the WCTU; Francis had been named after a prominent American temperance activist. Four of the children, including Lillian and Francis, qualified as grade school teachers.

Lillian attended Normal School in Winnipeg, and in 1896 received what was then termed a “Non-Professional Second Class Teaching Certificate.” A slight, soft-spoken, lady-like young woman, with a permanent limp, the result of a childhood injury, she taught for the next few years at a succession of rural schools, taking courses as well at Wesley College, Winnipeg, and earning a BA in 1905. One of the few female university graduates of her generation, she wanted very much to become a journalist, but she was qualified now to teach high school, and accepted a position at Morden, Manitoba.

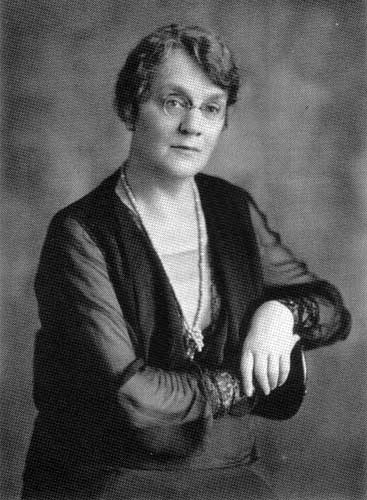

Lillian Beynon Thomas

Source: National Archives of Canada

Meeting the train from Winnipeg, she told a later interviewer, was one of the few diversions a small town offered, but unexpectedly one day she encountered John Dafoe on the station platform. Rather timidly she approached him: was there a chance for a girl, she asked, in newspaper work? There was very little money in it, Dafoe replied, but if she liked he would let her try. After the school year ended, in 1906, Lillian Beynon found herself in Winnipeg, with a new job and a new identity, “Lillian Laurie,” the voice of the regular Free Press Weekly feature, “Home Loving Hearts.”

The column, under Beynon’s direction, studiously avoided the stereotypically female romantic flutterings and domestic trivia which its title might be supposed to imply.

Instead, “Lillian Laurie” invited correspondence from farm wives and daughters across the prairies, discussing their profound social and economic problems, and exchanging encouragement and advice. She published letters from isolated women who suffered abuse at the hands of alcoholic husbands or fathers; she heard from abandoned wives who could no longer claim ownership of even the clothes on their backs; and time after time she received a cry for help from a widow who had lost the very roof over her head when her debt-ridden husband died. The column became familiar across the West, contributing in no small measure to the growth in the rural areas of women’s groups supporting reform. A working journalist now, Lillian Beynon became a member of the Canadian Women’s Press Club.

Despite their increasing numbers, women journalists had not been admitted to membership in the men-only Canadian Press Club. In 1904, the publicity director of the CPR, Col. George Ham, had taken a contingent of Canadian newsmen on a public relations junket to the fabulous St. Louis World’s Fair, much to the annoyance of the excluded newspaper women. The gallant colonel promptly arranged a similar expedition for the ladies, and, going further, he suggested that they form their own organization. Initially based in Toronto, and limited to women who were regularly employed on a newspaper or a magazine, the Canadian Women’s Press Club made little stir for its first year or two.

In the West, however, with their important women’s pages, the prairie newswomen quickly became the dominant and most active section of their Press Club. A convention was called for 1906, to take place in Winnipeg, and once more Col. Ham obliged. Recognizing the women journalists’ potential value to his railway for promoting prairie settlement, he provided free transportation to Winnipeg and back in private cars for all Club members, with an excursion to Banff as well for the entire party. Forty-four women attended the three-day meeting, resplendent in flowered hats and voluminous skirts, and the city welcomed the visitors with lavish and well-publicized entertainment. Newspaper reports documented the lady journalists’ trip through the prairies, with great fanfare at each stop, and the event consolidated the leadership of the Club’s western branch.

Eligibility for Club membership was extended to women who had published books or contributed to periodicals, and the Winnipeg branch set up comfortable clubrooms in the Industrial Bureau. Cora Hind was an active participant. Two Winnipeg women, Kate Simpson Hayes and Ethel Lindsay Osborne, served as national Presidents of the Club, and Harriet Walker, the co-owner with her husband of the city’s noted Walker Theatre, was elected for four successive terms as corresponding secretary, and named Honourary President in 1910. Emily Murphy, the “Janey Canuck” of several publications, became a Winnipeg member that year, and when she left the city to pursue a remarkable career in Alberta, she led the Edmonton branch of the Club to some signal victories in the battle for equal rights. Francis Marion Beynon joined her sister Lillian as a Press Club member, welcomed into a widening circle of like-minded progressives.

Francis Beynon had taught at Carman, Manitoba, and in 1908 she had moved to Winnipeg and had been accepted for a position at the T. Eaton Company, in the advertising department, a field in which women were still extremely rare. In November of 1908, the sisters were part of a group of Manitoba writers, men and women, who came together to form a literary society they called the Quill Club. Nominally meeting to explore matters of professional interest as writers, Quill Club members shared a concern with social and political issues, and their discussions turned frequently to the vexed issues of women’s disadvantagement, socially, legally, and economically.

After a dormant period of a few years, the franchise movement re-surfaced with new vigour. The Manitoba Labor Party included women’s suffrage in its platform in 1910; the Women’s Press Club entered the battle for enfranchisement; and the Women’s Labor League was organized, with Ada Muir at the fore, to improve working conditions for women and to press for the vote. As well as promoting “equal pay for equal work,” the League’s declared objectives included such characteristically “women’s” issues as better hygiene and household management and the eradication of liquor and prostitution. At a later stage the League would campaign aggressively for union organization, but in its early years it supported the suffrage groups in promoting reform in the middle-class issues of the Dower Law and the Married Women’s Property Act.

Lillian Beynon married a fellow journalist, A. V. Thomas, and both assisted in the work of the Stella Mission and in Woodsworth’s People’s Forum. Most extraordinarily for the time, Lillian Thomas came to the defence of unmarried mothers, demanding that they be helped, and protesting the stigma which society placed on them and their illegitimate children. Together with her sister and Cora Hind, she helped found the Women’s Institutes of Manitoba, the Homemakers’ Clubs of Saskatchewan, and the Women Grain Growers’ Associations in Saskatchewan and Alberta, and in 1911 she presided over the first annual Homemakers’ Convention in Regina.

The Quill Club seems to have petered out after about a year, but its overlapping membership with other reform-minded organizations became the nucleus of a focused, determined suffrage movement. If a vividly attractive leader was required, a leader arrived in the person of a most successful woman novelist, a member of the Woman’s Press Club. Early in 1910, the Club secretary had recorded, the Winnipeg branch was entertained at a tea in the home of Mrs. R. L. Osborne, at which the guest of honour was Mrs. Nellie McClung of Manitou, Manitoba. “The members,” said the minutes, “enjoyed meeting the bright little authoress of Sowing Seeds in Danny.” The next year, the McClung family moved to Winnipeg, and the “authoress” joined the Winnipeg sisterhood of women writers.

Nellie Leticia Mooney had been six years old in 1880, the youngest of six children, when the Mooney family settled in the Souris River valley, south of Brandon, Manitoba. Arriving at St. Boniface, across the Red River from Winnipeg, they loaded all their possessions on two creaking ox-carts, and trudged beside the carts to their new homestead. They lived for the first few years in a one-room log cabin, with the nearest railway station two hundred miles away, and the winter’s accumulation of mail delivered in the spring. At first, there were too few children in the district for a school; a schoolhouse was built when Nellie was ten, and it was only then that she learned to read.

Nellie McClung

Source: National Archives of Canada

As her girls grew up, Mrs. Mooney set some decidedly conventional standards of behaviour. They were not to be “forward,” they were to be properly respectful of men and their judgment, they must always be accompanied in public by their father or a brother. On the other hand, Nellie’s mother was a firm believer in the right of all children, girls included, to a good education, and Nellie’s older sister, Hannah, went off to Winnipeg to qualify as a teacher. At the age of sixteen, with only five years of formal schooling, Nellie followed suit, and earned her Normal School certificate the following year. The school principal had one piece of cogent advice for the young women of the graduating class. “Demand decent salaries,” he said, “and wear clean linen.” Fond of pretty clothes, and rather vain about her well-shaped hands, Nellie would always manage in the future to make her most stringent demands in her most becoming dress.

In 1890 she went to teach at Manitou, Manitoba, boarding with the family of the Rev. James McClung, the newly arrived Methodist minister. Annie McClung, his wife, was President of the local chapter of the WCTU, an ardent champion of women’s rights and an early suffragist. Very quickly, the lively young schoolteacher came to the conclusion that Mrs. McClung was “the only woman whom I have ever seen that I should like to have as a mother-in-law”; and some of Annie McClung’s liberated convictions seemed to have rubbed off on her son, Wesley. After a few years of teaching, in 1896, Nellie and Wes were married, and Nellie settled down, to keep house and to raise the first four of her five children. The youngest was born later, in Winnipeg.

Nellie was to say afterward, however, that Wes was not one to insist that “his wife should always be standing behind his chair, ready to spring to attention.” Following in her mother-in-law’s footsteps, Nellie joined the WCTU, whole-heartedly supporting its battle to rid society of the scourge of alcohol. An avid reader since her year at Normal School, she had begun to set down her impressions of life in the West, and a novel emerged, Sowing Seeds in Danny. Its themes soon became familiar to Nellie McClung’s readers: politics, temperance, the unjust treatment of women. The book was published in Toronto in 1908, and became a best-seller in both Canada and the United States. More books followed, equally popular; Nellie joined the Dominion Women’s Press Club, and invitations to lecture and to make public appearances began to multiply.

In 1911, the family moved to Winnipeg. Nellie was received with delight as a member of the Women’s Press Club, and immediately elected branch president. The move brought her to the centre of the suffrage movement, with the interconnected membership of the Women’s Press Club and a number of leading women’s organizations: the University Women’s Club, which Lillian Thomas had helped found in 1909, the Winnipeg Women’s Canadian Club, and others. The visit to Winnipeg of two militant British suffragettes, Sylvia Pankhurst and Barbara Wiley, greatly impressed the Winnipeg newswomen, and the determination grew among them that a concerted drive to obtain the franchise for women must be undertaken.

The Political Equality League came into being in March of 1912, at the home of Mrs. Jane Hample, with Lillian Beynon Thomas as first president, and Cora Hind, Nellie McClung, Francis Beynon, and other prominent women journalists among the first members. Lynn and Winona Flett joined, and a number of progressive-minded men were welcomed into the ranks, including Fred Dixon and George Chipman. Unlike their counterparts in England, where newspaper headlines blazed the electrifying story of suffragettes chaining themselves to the railings in Westminster and beating their opponents with their umbrellas, the Manitoba suffragists consciously adopted a policy of peaceable persuasion.

The League set up a speakers’ bureau, sent representatives to address labour groups and farm organizations across the province, and collected signatures on a succession of petitions. It inundated ministers and newspaper editors with suffrage material, distributed pamphlets at concerts and country fairs and union meetings, and organized only the occasional demonstration, spirited but orderly. Even so, the reserved Lillian Thomas confessed, in her later years, that she had been acutely embarrassed on those occasions when, as a public gesture of support, she had forced herself to wear the suffrage sash across her bosom, proclaiming “Votes for Women.”

The opposition Liberal Party, in the 1910 election, had included women’s suffrage in their platform. They had lost the election, but a growing body of support for the enfranchisement of women was becoming evident at last. The Grain Growers’ Association and the Trades and Labor Council declared their support. Fred Dixon, now becoming increasingly prominent as the candidate of a moderate labour grouping, joined the Political Equality League and was elected secretary-treasurer, together with his wife-to-be Winona Flett as superintendent of literature. In 1913, Conservatives once again blocked a suffrage bill, and the Liberal Party, sensing a potential advantage in its campaign to oust the Tories, indicated some cautious support of the suffragist cause. Nellie McClung and Lillian Thomas addressed the 1914 Liberal convention, the first time in Canadian history that women had been offered so public a platform.

As the provincial election of 1914 approached, the Equality League announced an entertainment to take place on January 28 at the Walker Theatre, a mock parliament staged by its members, with a reversal of roles, depicting a society in which women ruled and men were sheltered, and with the well-known “authoress,” Mrs. Nellie McClung, in the role of the premier of the province. Lillian Thomas, who wrote and organized the satire, may or may not have been aware of the earlier extravaganza starring Amelia Yeomans, but she had been highly amused by a similar performance in Vancouver, where the same battle for the vote was being waged. It was on the day before the show was to take place that the delegation representing reform-minded associations in the province had made its visit to the legislature, and Nellie McClung had hurled her challenge at Premier Roblin, “Give us our due.”

Thoroughly exasperated by Roblin’s fulsome obtuseness, Nellie had flared out angrily that it was high time women took a hand in the conduct of society, to correct such blatant wrongs as alcoholism and prostitution. Desperately poor girls, she protested, were driven by hunger into prostitution, and the men who battened on their misery faced nothing more than two years’ imprisonment, “the same punishment that is meted out to the man who steals a tree or shrub valued at twenty-five dollars.” The gallery applauded, but Roblin continued to maintain blandly, “Nice women don’t want the vote.”

In the midst of her explosion, Nellie had been taking note of the premier’s every gesture and pompous inflection, from the way he “caught his thumbs in the armholes of his coat, twiddling his little fingers and teetering on his heels,” to his “loud, masterful commanding voice which brooked no opposition ...” “We’ll get you yet, Sir Rodmond,” was her parting shot.

At the Walker the next evening, presiding over a legislature of women, she brought the house down with her cheeky enactment of a female Sir Rodmond. Flanked by unruly, misbehaving “legislators,” played by Cora Hind, the Beynons, Mary Crawford, and others, the “Premier” dispatched the business of the “House” with imperious finality. A petition to outlaw such dangerous items of men’s clothing as six-inch collars and scarlet cravats; a petition to provide labour-saving devices for men: men’s fragile nature must be shielded. An “opposition member” presented a bill to establish dower rights for men; the “government members” stopped their noise long enough to vote the measure down.

Then came the highlight of the entertainment, as a delegation of men—actual men—trundled in a wheel-barrow spilling over with petitions pleading for “Votes for Men” and for permission to take charge of their own wages. The “Premier” rose to the full dignity of her barely five feet, and, alternately twiddling her fingers and roaring like a soprano lion, she proceeded to put the petitioners in their place. “We wish to compliment this delegation,” she said, “on their splendid, gentle, manly appearance. If, without exercising the vote, such specimens of manhood can be produced, such a system of affairs should not be interfered with ... Politics unsettles men, and unsettled men means unsettled bills, broken furniture, broken vows, and divorce ... The modesty of our men, which we reverence, forbids us giving them the vote. Man’s place is on the farm ... Good men,” she said, “shrink from the vote as from a pestilence ...”

The audience rocked with laughter at the send-up of the unfortunate Roblin, and for the next few days the ladies’ entertainment was the talk of the town. There were repeat performances at fifty cents a ticket, and the proceeds enabled the Political Equality League to continue its campaign.

A provincial election was called for July of 1914, and Fred Dixon ran as an Independent candidate, throwing his weight strongly behind women’s suffrage; and among the most active of his campaign workers were the leading members of the Political Equality League. The Voice announced a Dixon election rally to be held at the Oddfellows’ Hall on 22 April, with Mrs. Nellie McClung, “famous as an author and for her splendid advocacy of women suffrage,” as one of the speakers. There was standing room only at the Oddfellows’ that night, including “ladies, who were present in large numbers,” as Mrs. McClung repeated once again the central suffragist argument: “all sane adult persons [must] have equal voice in the making of laws which they have equally to obey.”

Lillian Thomas took the rostrum at an election meeting of the Labor candidate in the working-class suburb of Transcona, complimenting “labour men” on their “proper grasp of the fundamentals of democracy,” and on their sympathy with the aims of the Political Equality League. She was followed by Nellie McClung, pleading for the right of women to vote, in order to safeguard the home and to protect the workers’ interests as wage-owners.

Appearing indefatigably at rallies for other pro-suffrage candidates, the suffragists were sure that they had dealt the entrenched Roblin Tories their death blow, but although Dixon won, the Liberals lost once again.

Across the fertile farmlands west of Winnipeg, in a scattering of small towns, the homesteaders of the area maintained a vigorous community life. Government-funded adult education programs brought farm people together, the men to study such topics as crop management and marketing, the women to learn the latest techniques of sanitation, child care, nursing, and food preservation. Rural life demanded a degree of cooperation among neighbours; the Grain Growers’ Association made an early appearance, and with the encouragement of the men, the women’s auxiliary developed a lively identity of its own. Politics held as much fascination for rural people as for city dwellers, and current issues such as temperance and woman suffrage were hotly debated.

Gertrude Richardson, circa 1912

Source: Barbara Roberts

In 1911, at the age of thirty-six, Gertrude Matilda Twilley came with her mother from Leicester, England, to her brother Fred’s homestead in the Roaring River district of Manitoba, south of the town of Swan River. She had participated in the suffrage movement in Leicester, and contributed to the local socialist weekly, the Midland Free Press. A devout Christian, she believed intensely that the only true Christianity was an active compassion for all suffering human beings, and a commitment to the cause of social and economic justice. Justice also called for the enfranchisement of women, so that in a world torn apart by male greed and violence the moral sensitivity that was particularly feminine might come to prevail. “I am only a woman,” she wrote; “no power is given to me to make just or more beneficent laws”; but she considered it her duty to comfort and help sustain all those struggling for spiritual regeneration and moral right.

Gertrude flourished in her new life, enjoying the proficiency she acquired in the domestic skills of Canadian farm women, and being accepted and esteemed in the intellectual and social life of the area. The editor of the Swan River Star, Andrew Weir, admired her writing, and began to publish her verses and articles. The Grain Growers had adopted a pro-suffrage resolution in 1911, and at a meeting in March of 1912 the Roaring River Suffrage Association was established, including as members both men and women, and with Gertrude Twilley as president and her sister Fannie Livesey as secretary. The Roaring River suffragists proudly claimed their association as the first in the province; they did not know of the earlier Icelandic groups or, some four hundred kilometres away in Winnipeg, of the coming together that same month of the Political Equality League.

Having married a prosperous local farmer, the new Mrs. Robert Richardson enthusiastically lent a hand in the Missionary Society, and later became its president. She helped found a Home Economics Society, where the women of the area both exchanged recipes and were instructed in business matters, so that they might better understand and influence their husbands’ dealings; and the National Council of Women of Canada invited her to become a contributor to their publication, Women’s Century. Richardson’s central interest was the Suffrage Association, working closely with the Grain Growers, who met periodically in the schoolhouse for a business social, with refreshments provided by the ladies.

One such evening offered an enlightening lecture on Direct Legislation, the philosophy of Winnipeg’s Mr. Fred Dixon, with an interlude of organ music and a monologue by Mr. Fred Twilley. With instinctive shrewdness, perhaps, the women cossetted their men, providing lavish refreshments, turning the occasion into a gracious social event. “It is impossible to get along without the Women’s Suffragette [sic] Association,” one very pleased gentleman glowed; “they acted the perfect lady, bestowing every kindness and attention on the men, and seeing that nothing was left undone that should be done.” Charmed, he called on men to “get down to business and demand the vote for women.”

Woman suffrage did not by any means have the unanimous support of all the men in the district; Gertrude Richardson was caught up in an anguished controversy on the subject in the columns of the Swan River Star. There were also rumblings of opposition when Lillian Thomas came from Winnipeg’s Political Equality League that fall to speak in Swan River and Minitonas, but Thomas aroused the indignation of her listeners by another tale of the injustice in the existing dower laws: abandoned with their infant child by her wastrel husband, one valiant woman managed single-handedly to raise her son to fine, successful manhood, only to watch him die and have the legacy he had bequeathed to her snatched away, with perfect legality, by the absentee father. An elaborately elegant tea honoured Mrs. Thomas, the Star reported, and she stayed at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Richardson.

In the provincial election of 1914, the Roaring River suffragists worked energetically to elect the party’s local candidate, William Sims, although Richardson herself had some reservations about identifying the cause with a political party. Premier Rodmond Roblin took a hand in the local campaign, holding a rally in Swan River to attack the Liberal position; Richardson was not impressed. Nellie McClung came to town, to stay with the Richardsons and to address an afternoon meeting for woman and a packed evening assembly of both men and women, with Mrs. Richardson proudly seated on the platform, wearing her gold-and-blue suffrage emblem. The Tories were returned to office, however, and the battle continued.

The Roaring River Suffrage Association voted in 1915 to reconstitute itself a branch of the Political Equality League, and Richardson helped organize additional sections in Oakhurst and Kenville and other towns in the Swan River valley. Invited to attend the February 1915 convention of the Political Equality League in Winnipeg, she joined a deputation once again confronting Premier Roblin; and at the business session the following day, she was elected first vice-president of the provincial division, in charge of organizing Equality groups across the province. Fired to new heights of ardour, she expressed her determination in a letter to the Midland Free Press:

We women are going to have our hands on the lever, that war and social evils may be crushed out of our world-life. And only bad men are afraid of it, only indolent, careless, selfish women are against it ... We have suffered and wept too long. The time has come for us to take the place we should never have vacated, the place given to us by God.

In 1915, the Roblin Tories were finally defeated by a scandal over the construction of the new Legislative Building, and the Liberals under T. C. Norris swept the polls. The Political Equality League had once again supported the victorious Fred Dixon, and on election night in August 1915, Nellie McClung stood beside him and three Liberal cabinet-designates on the balcony of the Free Press building, acknowledging the cheers of a jubilant crowd. With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, and the enlistment of men in the armed forces, women had entered the work-force in unprecedented numbers, and their role in the country’s economy could no longer be ignored. The Liberals had promised to introduce the long-sought suffrage legislation, and the battle seemed to have been won at last.

Norris was not quite ready to proceed. He would place the suffrage measure on the legislative agenda, he said, if the women could provide more evidence that Manitoba’s female population really wanted to vote. The suffragists swung into action once more. Petition forms were prepared and dispatched in the city and all over the province, as far north as Norway House, and women canvassed for signatures at church meetings and family gatherings and fall fairs; in Swan River, Gertrude Richardson and her mother collected signatures at the annual Grain Growers’ picnic. In December, a delegation of sixty men and women, headed by Lillian Thomas, presented the new premier with one petition containing 39,584 signatures, and a second one with 4,250 names, this one amassed single-handed by ninety-four-year-old Mrs. Amelia Burritt, of Sturgeon Creek, Manitoba. There seemed to be no turning back now.

A suffrage bill was made ready to present to the Legislature. Lillian Thomas picks up the story, in a letter to an inquiring scholar, years later:

A member ... who was in sympathy and who had worked with us told me he had seen the bill and it was giving us the right to vote but not to sit in [the legislature] ... I was naturally furious ... [and] I went down and asked to see the bill. The Attorney-General let me see it, with the understanding that I must not tell anyone ...

The newswoman’s contacts had paid off, but what was she to do now, having given her word?

I went home and telephoned every member of the League, and without telling them why, asked them to telephone their member and ask him if we were going to get the right to sit in the legislature. Oh boy! Telephones rang all over the city—not a member could get anything done.

Francis Beynon was in Brandon that day, attending a convention of the Grain Growers’ Association, and when she heard the news from her sister, she promptly raised the issue at the meeting. George Chipman threatened that rural support would be withdrawn from the Liberals unless women were granted full rights; and under pressure, Norris capitulated. “It was a long time before the premier would speak to me again,” said Thomas afterward, still pleased to have beaten the politician at his own game.

On 28 January 1916, Manitoba became the first province in Canada to extend the franchise to women, with the right to be elected to a seat in the provincial house. Members of the Political Equality League attended the third and final reading of the Suffrage Bill on that memorable day, and the League executive was granted a signal honour, never before accorded to any group in the history of the legislature. Seated on the floor of the Legislature during the regular session, The Voice reported, were Dr. Mary Crawford, president; Mrs. A. V. Thomas, Miss Francis Beynon, Mrs. F. J. Dixon, Mrs. A. W. Puttee, Mrs. William Ireland, Mrs. Luther Holling, and Mrs. James Munroe. Nellie McClung, equally deserving of the recognition, had by this time moved with her family to Alberta, and celebrated the victory from afar.

Other reforms followed in short order. A series of measures in 1917, 1918, and 1919 removed the electoral distinction between male and female property-holders in Manitoba, giving women equality with men in municipal and school board affairs. “It’s all over now, even the shouting,” exulted Lillian Beynon Thomas in her column; “the women of Manitoba are now citizens, persons, human beings, who have stepped politically out of the class of criminals, children, idiots and lunatics.”

The battle now shifted ground. Federal voters’ lists, by statute, were based on provincial entitlement, and the granting of the franchise to women in Manitoba, and in Alberta in March of 1916, seemed to indicate that at least in these provinces women would be able to vote in the Dominion election scheduled for 1917. Suffragists across Canada were outraged when the Borden government, bent on ensuring a pro-conscription vote, extended the ballot only to women with close relatives in the armed services, creating all manner of anomalies. It was not until 1920 that the distinction in the federal franchise between male and female citizens was finally removed. By 1925 women could vote provincially everywhere except Quebec, where fifteen more years would elapse before the right was granted to the female population.

Lillian Thomas had not been quite correct in rejoicing that women were now citizens and persons. Female citizens were now voters, but not officially “persons,” as a former Manitoba resident was to discover.

In Swan River, just before Gertrude Richardson arrived in the area, Emily Murphy had spent a busy four years, active in the WCTU and in building a hospital for the town, and had made a name for herself as the author of Janey Canuck Abroad and Janey Canuck in the West. Then, moving to Edmonton, she had involved herself at once in the suffrage movement, and in the fight to establish women’s dower rights.

Emily Murphy

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta

Rallying urban and rural women, taking her case to the newspapers, enlisting the help of any well-placed man who was willing to cooperate, Murphy finally succeeded in getting the Alberta legislature to act. In 1910, a bill improving women’s dower rights was put before the committee on legislation. Not satisfied with its provisions, Murphy demanded a hearing, and argued so effectively that a much stronger bill was sent to the provincial house, and passed. The Alberta Dower Act of 1911 provided that no man could dispose of property without his wife’s consent, and gave a wife title to one-third of her husband’s property during his lifetime and after his death. Slowly, as the twentieth century moved on, changes to property legislation in all the provinces would bring about more equitable provisions for women.

Continuing her writing career, Murphy was elected secretary in Canada of the Society of Women Journalists of England. She became a convenor of the National Committee of Peace and Arbitration in 1914, and during the war she was named a Lady of Grace of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem. Concerned with the treatment of women in the justice system, the Edmonton Council of Women, with Murphy an active member, had been lobbying the Alberta government to establish a women’s court, where women and children only would be tried, with women lawyers and volunteers available to guide the proceedings. The attorney-general agreed, and in 1916 he appointed Emily Murphy its first magistrate, and a second, Alice Jamieson, several months later.

Early in her career on the bench, having ruled against the case of one aspiring barrister, the new magistrate was startled to hear the young man angrily exclaim that her decision was of no value because she did not even have legal status as a “person.” She investigated and discovered he was right: under a British ruling of 1876, still valid in Canada, women were held to be “persons in matters of pain and penalties, but ... not persons in matters of rights and privileges.” Under a clause in the British North America Act, which entitled only “properly qualified persons” to be appointed to the Canadian senate, the archaic British legality effectively blocked women from the upper house. A long-drawn-out battle to clear out the impediment began. Nellie McClung, now living in Edmonton, had become fast friends with Emily Murphy, and the two joined forces in this new campaign to obliterate an inequitable law.

Over the signatures of Emily Murphy, Nellie McClung, Louis McKinney, Irene Parlby, and Henrietta Edwards—the “Famous Five,” as the newspapers dubbed them—a petition was sent to the Supreme Court of Canada requesting an interpretation of the crucial BNA clause. The decision was adverse: by Canadian law, women were not persons, not “properly qualified” for a wide range of the privileges of full citizenship. Undeterred, the five women referred their case to the Privy Council of Britain, and on 18 October 1928, they had their victory: banner headlines carried the Council’s solemn judgment: “Women Are Persons.” The exclusion of women from public office, the Council commented in its decision, was “a relic of days more barbarous than ours,” and the bar in Canadian law was declared null and void.

It had been a very long battle indeed.

See also:

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Famous Five Monument (Osborne Street, Winnipeg)

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Roaring River School No. 1215 (Municipality of Minitonas-Bowsman)

Page revised: 30 January 2022