|

|

|

Part 5. Education & Schools 1. Residential

Schools

2. Keeping the Language Alive 3. Hartland Goodtrack - Dakota Speaker 4. Names 1. Residential Schools  Before the Residential

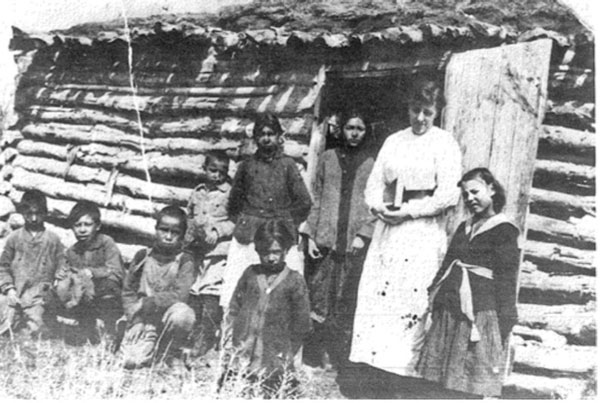

Schools were established there were some Day

Schools on Reserves. This one at Sioux Valley, was established in the

1880’s.

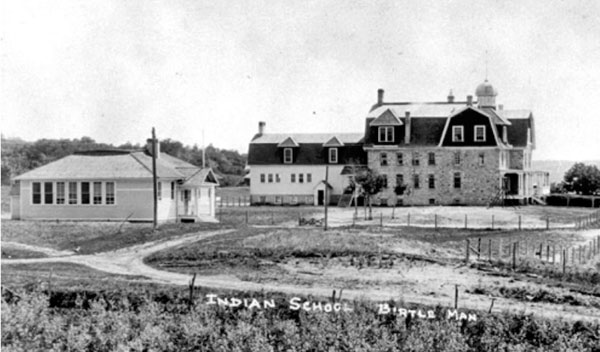

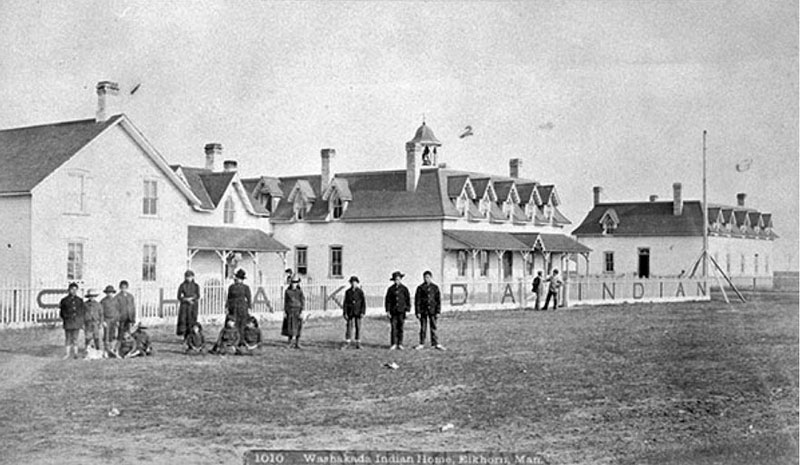

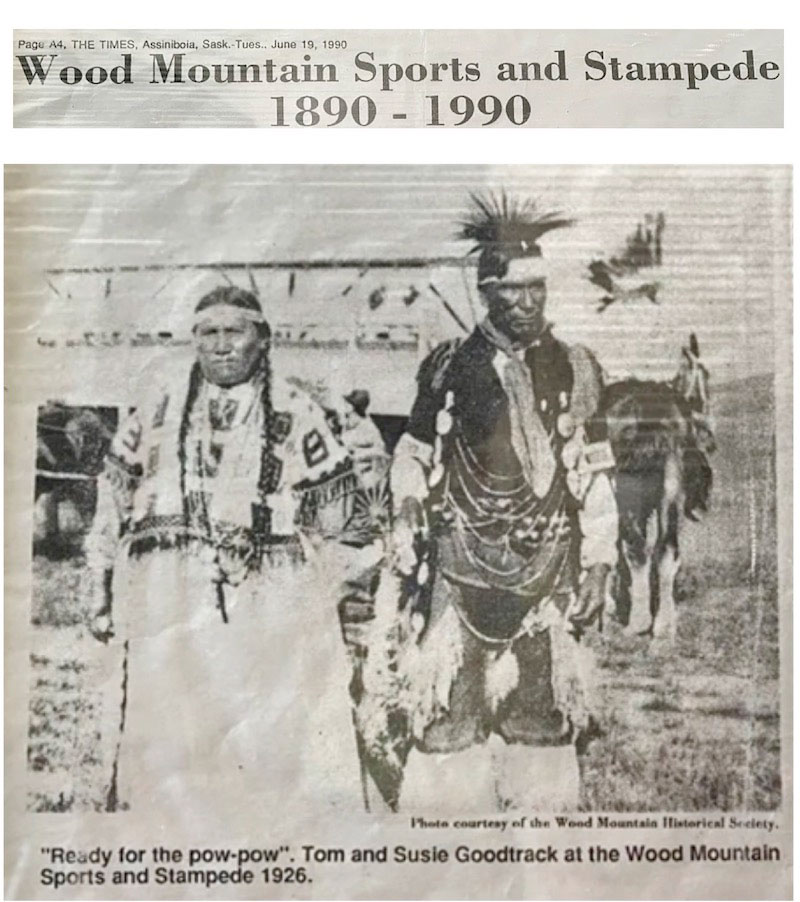

The original intent, to provided basic literacy, soon evolved into a far reaching effort to eradicate Native Culture, and the Residential Schools were established to fulfill that purpose. Children from Dakota Reserves in Manitoba were sent to schools established in Brandon, Birtle, Elkhorn and Portage. A language barrier, inappropriate curricula, inadequate school supplies, and poorly trained teachers all put the residential school children at a disadvantage. The half-day system that saw most of the children spend time working was counter productive and discriminatory to say the least. That and a poor diet, probably created an inattentiveness that also reduced their ability to learn. Unhappy, lonely children, with no family to support them, were unlikely to be in a mindset to learn, even if the knowledge was being presented by highly skilled teachers, which was rarely the case. The effect of residential schooling on young Native children is best summed up by Cree leader and residential school graduate, John Tootoosis: “When an Indian comes out of one of these places it is like being put between two walls in a room and left hanging in the middle. On one side are all the things he learned from his peo- ple and their way of life and their way of life was being wiped out, and on the other are the whiteman’s ways which he could never fully understand since he never had the right amount of education and could not be part of it. There he is hanging in the middle of the two cultures and he is not a white man and he is not an Indian.” Brandon  The Brandon Indian Residential School operated north of Brandon, from May 1895 to June 1972. The abandoned building remained here until August 2000 when it was demolished. There is also a graveyard on site, and another to the south, where some students who died while in residence were buried and more burials have been discovered . Recently, efforts by Sioux Valley citizens are underway to commemorate the sites. Frankin Brown shared this memory… I attended a residential school in Brandon. At the time, I didn’t think it was horrible. My cousin has 2 sets of twins. Because of the marital problems they were having, the children were apprehended for 6 months and then returned home. When they were apprehended, my dream about one of the older ones captured me. I thought about it and it took me back to the residential school where I went through the same things that she was talking about – lonesome for her parents and family. She is still traumatized today, home-wise, every aspect of her life is traumatized by that experience. She was 6 years old, when I was there I was 7. I was this size when I went to residential school and I went through these things, like a strap this long and this wide. Birtle A facility at Birtle known as the “Stone School” was built in 1882, as a school for the children of Birtle, For a short time it was used as building as a boarding school for children from surrounding reserves.   In 1894, a dedicated Indian Residential School was built at this site. A new brick building was constructed nearby between 1930 and 1931. Operated originally by the Presbyterian Church in Canada, responsibility for the facility transferred to the Canadian government in March 1969. It closed in 1972. Portage  The Portage la Prairie Indian Residential School, which operated from 1916 to 1975, is now used as a resource centre for the Long Plain First Nation. A golden eagle monument on the grounds is dedicated to First Nations people who were forced to attend residential schools. The building became a nationally designated historic site in September 2020. Oswald McKay shared this memory: remembers it this way…. My mother was in Portage residence school when she was turning six, or six already, until the age of 16, even though her parents and grandparents were at the village there, two miles to the west. I went to a funeral in Dakota Tipi, it was a traditional man that passed away- a traditional funeral. What he said at that time really hit me. He said. “imagine a community with no children.” That’s what these communities went through. Imagine the towns of Napinka, Melita, imagine that today with no children. So that not only changes the children, it changes the adults. Again when you don’t live through something, you don’t think of things Elkhorn  The Washakada Indian Residential School, in Elkhorn opened on 10 June 1888. It burned to the ground in the late 1890s and was replaced by a large, brick building in 1897, which remained open until February 1918. It was reopened in June 1923 and operated until permanent closure on 30 June 1949. In the recently published book, “Trailblazer in First Nations” Doris Pratt, (profiled elsewhere,) offers some insightful observations about here time at the school in Elkhorn.  Crosses were raised on the nearby cemetery by former staff and students during a reunion held in July 1990. A conversation with Oswald McKay on the challenges regarding the preservation of the Dakota Language. Is the Dakota language being taught in Reserve Schools? The teachers that have gone on to get their teachers degree to teach the curriculum, they are mostly without a language background. The ones who have the language are 50 and over, who don’t have a teaching degree, so the administrators or whoever pushes the curriculum say that the people who teach the Dakota language must be certified teachers and where do you find one who is fluent. These are some of the roadblocks. It’s difficult. You have to be committed to teaching the language and do whatever you have to do to ensure that the teaching is there, the physical environment of teaching in the classroom, you have to pay the teacher. It takes political efforts have to be there, sometimes our councils, they put that on the back burner you know, because of other political matters. I know there are elders in the community who would go to the school and offer their knowledge. But you know it’s not enough. What we need is whole language immersion. We had our own classroom as a family, and it was working, but once the kids get big then they went to regular school. So we tried just to see if it would work and it did. We ran the school for 3-4 years, but the kids got older. The way it’s happening right now, the young people in the younger grades the kids will go to school. They learn 1,2,3 colours, place names. That’s all they learn. When they get back to their homes after school is out, their parents don’t know that, those words so it’s not reinforced at home. So the child knows some words, and maybe short sentences but the young parent doesn’t know. And neither do their parents. So it’s also third generation or 4th where the language was lost. So essentially, teachers, who have to be accredited often aren’t fluent in Dakota. We need to use the resources of the community - folks who are fluent, to work with the school. Then we have to find a way to reinforce the training when the child leaves the school? Someone needs to come up with a way to take the seniors, your generation that can speak the language working with the teacher who can learn from them. But then you’re already paying the teacher, and then you have to pay someone else and then you have seven other budget items to work with. Exactly, it’s political will and it seems that the politicians that run our reserve, they seem to be getting younger and younger. They don’t speak the language At that stage of their life, or in the life of the Dakota there may be this common thought that the language is not important. Well we live in a world where there are so many other pressures. Now most people say that. Now I’m really interested in what is being done elsewhere. Ok the whole part of North America from here right down to Montana, there are lots of Dakota people. Have places in the States, coming up with a interesting programs? Today, Hartland Goodtrack, a descendant of Lakota followers of Sitting Bull who came to Canada following the Battle of Little Bighorn, is worried about the future of the his language. He is one of the last fluent Lakota speakers in Canada. A CBC report outlines his life and his thoughts, presented here in excerpts from that report. Hartland Goodtrack grew up in Wood Mountain, the only Lakota community in the country. He and his wife live on Standing Buffalo Dakota Nation.  Harland Goodtrack - by Richard Agecoutay/CBC) He remembers his grandma telling him how they fled the U.S. to the Canadian border with other families after the Battle of the Little Big Horn, led by the great Lakota leader Sitting Bull. Although Sitting Bull and others returned to the United States in 1881, 37 families remained in Canada and founded Wood Mountain. Today it is the only Lakota community in the country. Goodtrack was born in 1938 at his grandparents' small home in the community. His Lakota name is Eya Ta-Gi-La, which means stingy in the Lakota language. Goodtrack's grandmother decided they were going to raise him to learn the Lakota ways. Lakota was his first language, and he didn't learn a word of English until he was six years old. After his grandmother passed away when he was five, he was raised solely by his grandfather, who took him along to meet farmers to sell fence pickets. Goodtrack said the RCMP wanted to send him to residential school, but his grandfather stood his ground and refused, so Goodtrack was able to retain his language, unlike others his age. Now he is one of its last remaining fluent speakers in Canada.  Hartland Goodtrack's grandparents Tom and Susie Goodtrack, who raised him, pictured in a newspaper spread. (Louise BigEagle/CBC) A Sioux Pow wow, was a feature at the Wood Mountain Sports and Stampede. It featured traditional drumming and dance. Men sany the old songs to the beat of drums. Sometimes individuals would step out to display a War Dance or a Chicken Dance. Hartland’s father, Tom was known for his performances. Events such as this helped keep Dakota culture alive. Goodtrack worked in grain elevators when he grew up. Along the way he met his wife Evelyn, a Dakota woman from Standing Buffalo Dakota Nation. Yhey are now retired on Standing Buffalo Dakota Nation. Goodtrack was able to retain the Lakota language for all these years, even after living in the modernized world, but he wishes he would have passed it on to his children. "My biggest regret is I didn't teach my girls Lakota," said Goodtrack. The Lakota language is considered critically endangered in Canada, meaning it is at risk of falling out of use because it has few surviving speakers . Goodtrack was 17 when his grandfather died. After that there was only one person left he would talk to in Lakota, Jim Wounded Horse, but he died when Goodtrack was 28 years old. Goodtrack said he rarely spoke Lakota for some time after that. Now, he has been trying to speak it as much as he can. Luckily for Goodtrack, Lakota is mutually intelligible with the two dialects of the Dakota language and with Nakota, as all are languages of the Sioux family. So when he runs into a Dakota or Nakota speaker, they can understand each other. For instance, the word "friend" is "kola" in Lakota, "koda" in Dakota, and "kona" in Nakota. Also, each language differs slightly depending on whether a women or man is talking, but only a fluent speaker would know the difference. One thing Goodtrack and his family have done to help maintain the language is work with the File Hills Qu'Appelle Tribal Council on an app that teaches Lakota words and phrases. They helped with the basics of the language, like introductions, phrases, numbers and colours. Goodtrack said it was fun for them to hear themselves speak on the app.  One of his daughters, Roberta Soo-Oyewaste, is taking online Dakota classes with the University of Minnesota. She said she is proud to be learning a language and hopes to learn enough to chat with her father, even though it is slightly different from the Lakota he speaks. She said learning language gives her strength and takes her back three or four generations, to the Battle of Little Big Horn. Soo-Oyewaste wants her children to know the importance of her grandfather's history, and that they come from a warrior lineage. "You want to give them exposure and for him to share his knowledge about the language," said Soo-Oyewaste. "Every language has a spirit and that's the first thing we learn, right? It's the spirit of the language and the sacredness of the language, and we have to embrace that." https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/lakota-man-may-be-last-fluent-speaker-canada-1.6796711 Wawanesa, “no snow”; Napinka is “to run or move away with fright.” When Dakotas were in that area, something happened there that gave it that name. Minnedosa - “fast-footed water.” Miniota is “lots of water.” Hamiota – it was Ham-an-i-o-ta but people can’t pronounce the h, that’s why it’s called Hamiota. The name came after the tracks came through Hamani is a train. The train goes through there lots. Neepawa is living snow. Wash-ka-da, it’s is “good.” How did that name come about? the settlers must have been traveling, met some Indians there in that area of Waskada. They probably wanted to go further west. They wanted to know “where are we? “ Where is this? So the interpreter might have said something they wanted to see something good and they say “Washkada.” Kola is “friend” in Lakota. In Saskatchewan, there are a few Lakota names. Wapella means “barking dog,” As you go along further west there are some Lakota names, so that is a division of Dakota prior to confederation of Dakota and Lakota. |