|

|

|

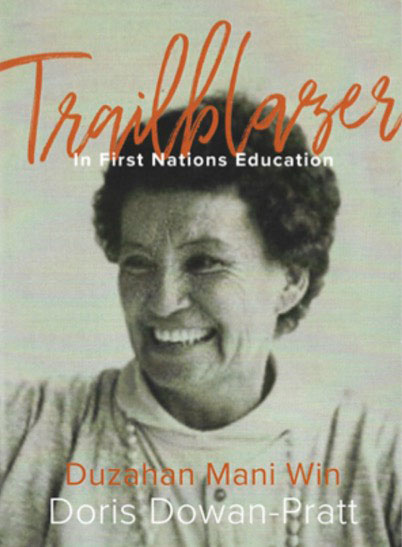

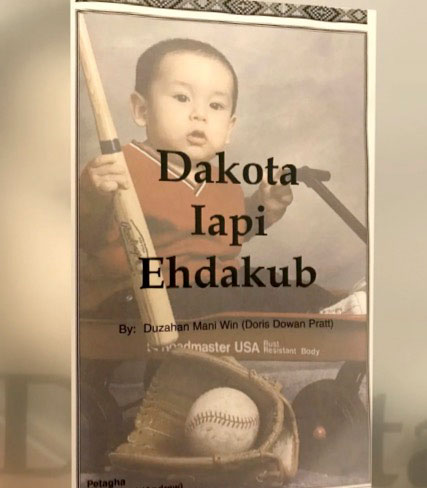

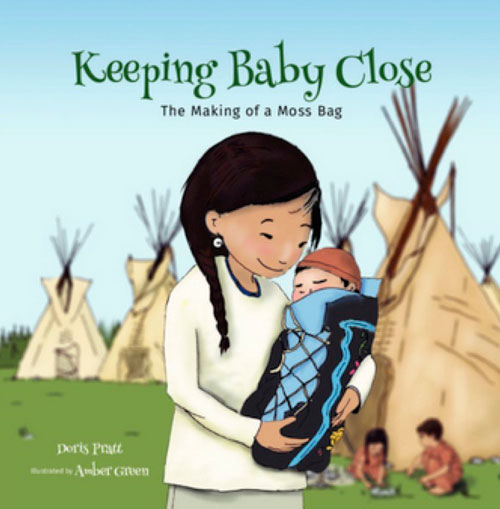

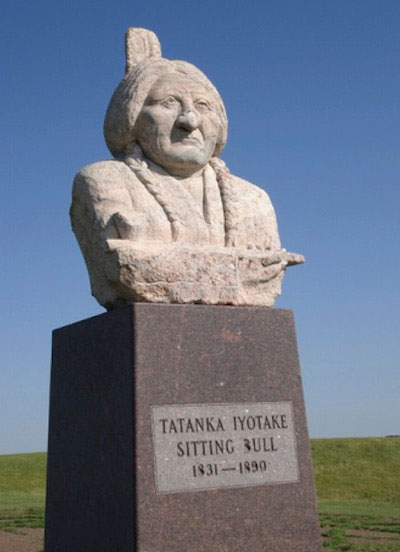

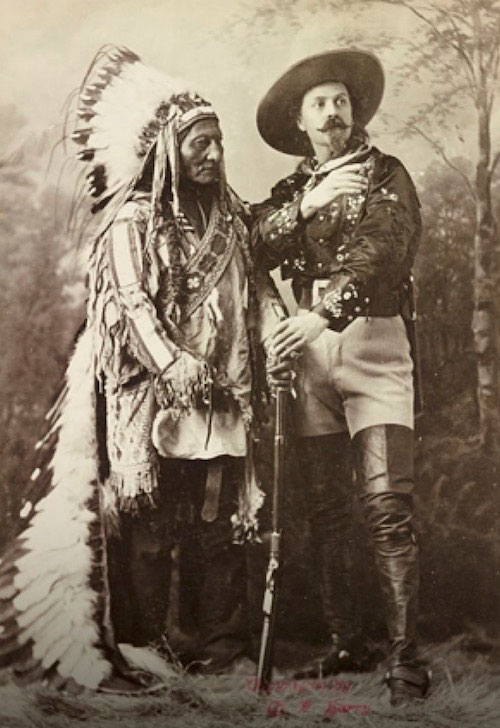

Part 6: Notable People Doris Pratt was born February 10, 1936 in what was then known as the Oak River Indian Reserve now known as the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation or as known by the Dakota people “Wipazoka Wakpa”, where she resided and continues to work in the education field as the Elder advisor for the Sioux Valley Schools until her passing in 2001.  Elder Pratt’s grandfather, One-Face (Ite Wanzida), was known as one of the first Dakota men who returned with his family, along with other families, to the North Country. Her parents were Bessie and Demas Dowan, whom she proudly acknowledges provided the spiritualty, language and cultural foundation that have been the guiding principles in all that she has achieved in her lifetime. Doris was is the youngest of nine children; at the age of 6 years she attended Anglican Day School on the Oak River Reserve. The following year they were moved to the Residential School in Elkhorn Manitoba, she remained there until being moved to Portage la Prairie Indian Residential School. Although her mother truly believed that Doris should receive a formal education, at the age of 16 her mother refused to send her back to Residential School. Elder Pratt returned to live in her community, where as she stated, she “received the best kind of education.” She was taught to work hard by making a living and surviving off the land, helping her father with chores, trapping, and working in the agricultural fields that surrounded their community. She was a horse-woman, known for her excellent riding skills. Elder Pratt treasures these memories, she believes the teachings she received from her parents, extended family and community molded her to becoming the strong Dakota woman she is. In the early 1970’s, through the encouragement of the Kindergarten teacher at the Sioux Valley School, she applied to the Indian Metis Project and Careers Teacher Education (IMPACTE) Program at Brandon University. She acknowledges the many people, such as the Kindergarten Teacher, who believed in her, providing encouragement, inspiration and support to achieve great things in her lifetime. She practices this same model and has encouraged many young First Nation people to pursue their dreams, many who have become Teachers like her. She coordinated the BUNTEP Program in Winnipeg and started the same Program in her own community in the early 2000’s. Her post-secondary education includes a Bachelor of Teaching Degree, Bachelor of Education (5-year) and Masters of Education Degree all from Brandon University. Doris also spent five summers at the American Language Institute Development Program at the University of Arizona and achieved an Education, Culture & Language Specialist Degree in December 2004. She considered her formal education challenging, and promotes the philosophy that First Nations people can achieve their goals through hard work, and that education is the key for success and the advancement of First Nations. Pratt devoted nearly 50 years to preserving the Dakota language and dialects specific to Manitoba and Canada. Doris told CNC News in 2018 that her work to preserve the language formally started in 1972. She said she felt she needed to do something to preserve the language, which was her first language, after becoming frustrated with a lack of resources. "I felt nothing was done for Dakota language that I knew of in Canada," Pratt said Informally, however, her work to save the language became while she was attending residential school in Elkhorn, Man., when she said she would have to translate English instructions into Dakota for students who couldn't speak English. She would continue her work in university, while attaining a teaching degree and a master's in education. She was the recipient of a lifetime achievement award from YWCA Brandon for her work. Pratt also studied at the University of Arizona, home to the American Indian Language Development Institute. "I loved it," she said of her time there. "It was hot as blazes, but I didn't care." Pratt wrote her first dictionary on the Dakota language in Canada in 1982 and wrote several more books and glossaries over the years. She was also an elder advisor for the school in Sioux Valley, which is located about 40 kilometres west of Brandon, Man. he also spent years translating documents, such as census forms and documents from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, from English into Dakota for the federal government. However, one of her dreams was to see an institute like the American Indian Language Development Institute created in Canada to preserve Indigenous languages from across the country in one place. "That's somebody else's bag of tricks now," Pratt said during the November interview. While she said at the time her work was largely done, she boasted about still getting calls daily from people needing help translating words into Dakota from English. She said while residential schools may have suppressed traditional languages, and in some cases driven them to extinction, there is time to save those that are still being spoken, and hoped people in her community stepped up after she died to keep them alive. Puppet gives Manitoba First Nation kids a hand at learning Dakota language. "There's nothing stopping you from taking it back," Pratt said. "Learn the language. It empowers people when they have their own. "Your language, take it back." She said while residential schools may have suppressed traditional languages, and in some cases driven them to extinction, there is time to save those that are still being spoken, and hoped people in her community stepped up after she died to keep them alive. Puppet gives Manitoba First Nation kids a hand at learning Dakota language "There's nothing stopping you from taking it back," Pratt said. "Learn the language. It empowers people when they have their own. "Your language, take it back." Elder Pratt has been involved with AMC since its inception – • she participated at the Manitoba First Nation Education Directors Meetings; • then at the FAI Council of Elders Table; and • since 2006, at the AMC and TRCM Council of Elders Elder Pratt has received several awards recognizing her achievements including: • Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Medal – Knowledge Keepers • Ka Ni Kanichihk – Keeping the Fires Burning – Grandmothers Award • Aboriginal Circle of Educators – Trailblazers Award • Manitoba First Nations Education Centre – Dakota Language Recognition • Women of Distinction Award – Lifetime Achievement • Nominated for Aboriginal Achievement award in Education Elder Pratt has dedicated her life to education and more importantly to ensuring the Dakota language was preserved and promoted in the Dakota communities she worked in as a teacher, principal, director of education, and as a professor at the university level. The Writings of Doris Pratt Elder Pratt was the author of several books, including: The Dakota Oyate (March 2016) Echoes of Our Dakota Ancestors "Echoes of Our Dakota Ancestors includes chapters based on the months of the year, with each section featuring stories, poems, and other resources in the Dakota Language. Doris Pratt, a long time Dakota language teacher and material developer shares this illustrated Dakota collection to help students learn and practice the language."--   Keeping Baby Close: Making of a Moss Bag The moss bags of the Plains Indians kept babies safe, content, and part of daily life. This two-part book first explores the features and purpose of moss bags, along with softly coloured illustrations. The second part includes step-by-step directions for making a moss bag, accompanied by explanatory photos. Discover more about moss bags, the ingenious creation of early mothers and grandmothers living close to Mother Earth. At the time of her passing she was nominated for the Lieutenant Governor’s Award for Historic Preservation and Promotion. Sitting Eagle was the Grandson of H'damani, the Chief who had led the small band of Dakota Santee into the Turtle Mountain region in 1862. He remained on IR#60 after the government bought out the rest of his band and re-settled them at the Oak Lake Reserve. He lived by trapping and selling handicrafts and by all accounts was well respected in that region. While many accounts from the Melita / Sourisford area see him as a Pipestone Chief, those from the Deloraine area emphasize his roots on Turtle Mountain. Gordon Elliott, who knew him well, and in fact taught him to read using an old “Sweat Pea” Reader, recalled that he was with the Pipestone Band. The Sitting Eagle spent considerable time in the Sourisford area where he also maintained a small lean-to dwelling. He was a regular visitor, a familiar and welcome figure to many farm families in the region. His story begins in the 1890’s when the government set out to close IR#60 in the Turtle Mountains. He and his Grandfather H'damani were among the few who declined a $200 government pay-off to relocate to a reserve near Pipestone. By 1909, only H’damani, his grandson Chaske (later known as Sitting Eagle) and a few others remained. Many residents of the Deloraine and Melita areas recall his habit of dropping in at mealtimes, sharing stories, making the children bows and arrows. He would exchange meat and fish for whatever the homemaker had on hand, and accept a spot in the hay- loft for the night. He could be spotted at the train station shipping furs. He attended fairs and celebrations, in full traditional attire, and sold his hand- crafted baskets and other items. At some point he did relocate to the Canupawakpa reserve, but during the final decades of his life he seems to have mainly lived in a small log cabin on IR#60 trapping, hunting and travelling the area. Joseph Sandy, a grandson of Sitting Eagle’s brother, remembers him journeying from Canupawakpa to Turtle Mountain. Sitting Eagle died alone in his log shack in April of 1944 and is buried in an unmarked grave in the Deloraine Cemetery. Remembering Sitting Eagle Perhaps the way to get the most accurate portrayal of Sitting Eagle is through the memories recorded in a series of interviews and writings involving some of the many people who knew him. Although their memories provide some conflicting information, a picture of the man does emerge. Lois Teetaert, reminiscences from 1930-40’s “In fact he used to come over to our place, oh for about May-June on and stay there overnight, but he’d never stay in the house. He’d sleep in the loft where the hay was. I remember him when we used to come to Deloraine Fair. He used to help park cars sometimes. “He’d always pat you on the shoulder or something like that. No, I was never scared of him.” Hattie VanMackelberg “One night he brought me a chicken and asked me if I would cook it for him. “He said the Indians believed that for every new baby that’s born, that is the spirit of a person who has died. The spirit comes back in the form of a new baby.”  Sitting Eagle in Melita ca. 1935 He surprised some by spoking of world affairs, mentioning the treaty signed to end WW1, and his fascination with the League of Nations. He was a totally unexpected person. Adapted from a story written for Vantage Points 4 and from a Radio Broadcast by David Neufeld.  (1920-2005) Eva McKay a Traditional Elder, Sweat-Lodge holder and Healer from Sioux Valley Dakota Nation spent her life serving her people and her community. Born in 1920, Eva grew up two miles south of Portage la Prairie. In 1934 she moved to Sioux Valley First Nation. There, she was the first woman elected to the Band Council, where she served four terms. Among her life’s accomplishments is the establishment of the Brandon Friendship Centre in 1964 and the Manitoba Indian Women’s Association in 1969. She, among others, brought education under local control with the completion of the Tatiyopa Maze School at Sioux Valley in 1979. She served on the National Parole Board in 1996, and was actively involved with the Canadian Panel on Violence Against Women. Eva McKay was a cultural worker for 10 years with the Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council. Also active with the Dakota Ojibway Child and Family Services agency, she served as a foster parent for teenagers for many years—this alongside raising 12 children of her own. A respected elder, Eva was on the Self-Government Advisory Committee for Sioux Valley. For 30 years she was a member of the Advisory Elders Panel at the Brandon University. Eva McKay died in 2005. Eva McKay was one of the co-founders of the Brandon Friendship Centre, established in 1964. She also helped establish the Manitoba Indian Women's Association in 1969. The efforts of Eva and her colleagues for local control of education in Sioux Valley resulted in the 1979 completion of the Tatiyopa Maze School. Eva was very active locally and in 1973 she organized a women's group called Ladies Owoju Club. Their objective was to have an Elders complex built. The Dakota Lodge was completed in 1983. She was a foster parent for teenagers for many years. The YMCA of Brandon presented Eva with the Woman of Distinction Award in 1988. She also received the Canada 125th Commemorative Award for public service in 1993. Eva served on the National Parole Board in 1996. She was actively involved with the Canadian Panel on Violence Against Women. She is on the Self-Government Advisory Committee for Sioux Valley. Eva has been a member of the Advisory Elders Panel at Brandon University for over 30 years. Eva was an elder adviser at the beginning of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry process of 1991.  This Monument to Sitting Bull placed on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation near Mobridge, South Dakota, in 1953 is a tribute to a complicated and accomplished Dakota leader, with a strong connection to Canada and links to Dakota people in Manitoba. The sculpture by Korczak Ziolkowski was created in 1953, long after the events for which we remember him. Sitting Bull was born in 1831 near Grand River, Dakota Territory in what is today South Dakota. He was the son of Returns-Again, a renowned Sioux warrior who named his son “Jumping Badger” at birth. The young boy killed his first buffalo at age 10 and by 14, joined his father and uncle on a raid of a Crow camp. After the raid, his father renamed him Tatanka Yotanka, or Sitting Bull, for his bravery. Sitting Bull soon joined the Strong Heart warrior society and the Silent Eaters, a group that ensured the welfare of the tribe. He led the expansion of Sioux hunting grounds into westward territories previously inhabited by the Assiniboine, Crow and Shoshone, among others. Sitting Bull first battled the U.S. Army in June of 1863, when they came after the Santee Sioux (not the Dakota) in retaliation for the Minnesota Uprising, He faced the U.S. military again at the Battle of Killdeer Mountain on July 28, 1864, when U.S. forces under General Alfred Sully surrounded an Indian trading village, eventually forcing the Sioux to retreat. Around 1869, he was made supreme leader of the autonomous bands of Lakota Sioux—the first person to ever hold such a title. In 1874, gold was discovered in the Black Hills, a place sacred to the Sioux and within the boundaries of the Great Sioux Reservation. The U.S. government reneged on a treaty, moved the reservation to a spot 240 miles distant, and insisted that those who dared resist move to the redrawn reservation lines by January 31, 1876 or be considered an enemy of the United States. Sitting Bull was expected to move everyone in his village an impossible 240 miles in the bitter cold. Defiant, Sitting Bull refused to back down. He mustered a force that included the Arapaho, Cheyenne and Sioux and faced off against General George Crook on June 17, 1876, winning victory in the Battle of the Rosebud. From there, his forces moved to the valley of the Little Bighorn River. But that victory was short-lived and facing a choice between inevitable extermination, and being allocated a Reserve by a Government they had to reason to trust, Sitting Bull and many of his followers opted to take refuge in Canada. The move to Canada, coming as it did alongside the dramatic destruction of the bison herds, caused controversy and hardship. Perhaps inevitably the people opted to return and take their chances on a US Reseve.  Sitting Bull, famously toured the World with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show before returning to his Pine Ridge Reservation where before long he again became involved in controversy, He had been making some trouble, related to his association with the Ghost Dance Movement which authorities found threatening, and the army finally decided to place him under arrest.  Early in the morning of December 15, 1890, the Sioux police entered Sitting Bull’s log cabin and dragged the old chief from his bed. “Catch the Bear,” leader of Sitting Bull’s bodyguard reacted and before the dust had settled, Sittine Bull and twelve were dead and three were wounded. Sources: RCMP Quarterly Vol. 42, No. 3 Summer 1977 p. 41 - 45 When Sitting Bull Left Canada By Dr. George Shepherd OM: That’s the famous statement that Sitting Bull made, I think he made it before the battle. “Let us put our minds together and see what life we can make for our children.” From when he made that statement, seven generations later, a renewed way of thinking, a new way of life is supposed to happen from when he made that statement 7th generation see what happens from there. That’s what there going to use as a model. I think people are saying, how true it is I don’t know, but we are in the 7th generation. The 7th generation is coming up. What kind of life are we going to make for our children? So when he made that statement and all the things that happened in between that until today should give us a good idea of what we make for our children and peace isn’t one of them. There is no peace yet as long as the Indian is still on the reservation. There is no peace because that is a prisoner of war camp, LD: It’s a..? OM: Prisoner of war camp, that’s what it is, basically . It’s a pogrom what pogrom really means: they select a place where they want to put certain people and they are going to keep them there until they die. Franklin Brown was born in 1953 in Sioux Valley. It wasn’t called Sioux Valley then, it was Oak River Reserve. For the original people of America, the United States and Canada do not exist under the Creator’s instruction or creation. Our issue today is that the Buffalo Nation People, the Dakota, never surrendered their land over to anyone. There were negotiations or talks that were held with not just the Dakota but the Cree and Ojibwa. They did not understand what the Europeans were saying and that’s the problem today. They never had an understanding of what they were signing. The Dakota never surrendered their rights and title. Under their constitution, and by their natural law they could not sell or surrender their land because God had created it. The Cree and Ojibwa have a different territory. The language identifies the nation’s territory. How can you say your land is my land? We need to understand specifically where your territory lies and my territory lies. I know where my territory lies. But I’m not going to tell you to get off my land. You should know better than that. You should ask my permission, and I will give it to you. In times before the European, there were no boundary lines but we knew how far you can go. Language identifies the nation In 1998-99 I was the chief administrator for Canupawkpa. All the Manitoba chiefs went to meet the Minister of Indian Affairs, Robert Nault in Winnipeg Each chief had an opportunity to talk. When it was my turn to speak, I said that I didn’t want to talk about what everybody was talking about I said, “What I want is for you to compensate back what you took away from us. You guys give my people 2000 head of buffalo and 50 sections of land. We’ll go from there, sustain ourselves and look after ourselves. Minister Nault was shocked at how I introduced myself. “I’ll tell you what,” he said, “I’ll give you that IR60.” “No, I don’t want it,” I said. “You should go see that land. We can’t survive on it.” I turned down IR60 ”OK. Maybe we need to sit down and discuss this further. We’ll see what we can do.” We were both serious because something had to be done. But then, two months later, I lost my election. Even when I lost my election, the minister still agreed to see me again. He said, “You know I would like to work with you. You need to go back and claim that seat again and come back. We will work on something.” One of the more interesting aspects of the relationships between the first Eurosettlers, and the Dakota people who lived here, is the difference a border could make. In pre- Euro-Settlement days, the border was theoretical at best, and ignored in practice. That worked for a long time, until the advent of European settlement and the conflict that was destined to ensue. South of the border that conflict escalated into warfare and Canada often became a haven for Dakota people fleeing from the U.S. Army. Somehow tribes and individuals, who south of the border had the reputation of being fierce warriors, were on this side of the border, peaceful citizens. If ever a native warrior came to our region with a bad reputation, though, that would be the Inkpaduta. He was a Chief of the Wahpekuta, a band of Santee Dakota.  To settlers south of our border he was notorious for being the leader of the bloody Spirit Lake Massacre in Iowa in 1857, and a participant in the Dakota War in Minnesota in 1862. He became known as the “scourge of the Plains.” For a time the popular press blamed him for every altercation involving the Dakota. Even some of his own people turned away from him for fear of European retributions on their villages when he was in the vicinity. His image as an elusive outlaw was bolstered by the fact he was never captured and never surrendered. Recently, however, historical reinterpretation places more emphasis on his uncompromising resistance to the European takeover of Indian lands. And more stress is placed on his long record of peaceful co-existence with settlers until provocations and hardships caused him to rebel.  An artist’s conception It is true that in 1857 he lead about a dozen or so warriors in attacks on settlers in the aforementioned Spirit Lake Massacre, actually a series of attacks, in which about 40 deaths were recorded and four women were taken hostage. It is likely also true that these raids were in retaliation for the murders of members of his family and the ongoing encroachment of settlers on Sioux hunting grounds. Inkpaduta was in Minnesota during the Dakota Uprising, and although he didn’t play a large role in that conflict, he was pursued aggressively by General Scully in the aftermath. After suffering two losses in battle he crossed into Canada where he spent time on Turtle Mountain before heading to the Montana Territory where he participated in the ongoing struggle between the Dakota and the U.S. Army. He is credited by some with being an ally of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, and with being part of the large coalition of forces that dealt General Custer a devastating defeat in 1876. These reports are likely exaggerated, as he was by that time an old man and quite blind. His sons and followers, however, did participate in that battle. Inkpaduta returned with some followers soon afterwards to the safety of the north side of Turtle Mountain. A newspaper report has him crossing into Canada with Sitting Bull. He and members of his family lived out the rest of their life in Canada. We may never be sure which way to see Inkpaduta, but we can be fairly certain that while in Canada, he lived a peaceful life. Both the Morton and Turtle Mountain local histories note his presence in the region. Other reports have him as part of a group of Wahpekuta Sioux who settled on the Canupawakpa Reserve near Pipestone. Most sources say he died in 1879 or 1881. U.S. sources cite, “the Brandon area” as his place of death. In 1934, two of his sons, Little Spirit (Wanagi Ciquana) and Charley Maku, and also a daughter, were living in the Pipestone region. All reports from the north side of the border agree that there was no trouble, from Inkpaduta or his followers. Sources Reflections - Turtle Mountain Municipality and Killarney, 1882- 1982. Inter-collegiate Press of Canada, 1982 Deloraine History Book Committee. Deloraine Scans a Century 1880 - 1980: Altona. Friesen Printers, 1980 Diedrich, Mark. Famous Chiefs of the Eastern Sioux. Coyote Books 1987 “Indian Battles in North Dakota.” 2015. <http:// indianbattles.weebly.com> Larson, Peggy Rodina. A New Look at the Elusive Inkpa- duata. Minnesota History Magazine, Spring 1982 Manitoba Free Press. The Sioux Indians. 21 July, 1877. pp6 Photos: Sacco, Cristiano. “Inkpaduta.” 2014. Farwest Italy. <http://www.farwest.it/?p=72 |