|

|

|

Part 4: The Turtle Mountain Reserve

In

1862, Chief H'damani led his Dakota-Santee band into Manitoba,

fleeing from conflict with the U.S. Army to the south. H’damani claimed

to have bought the land referred to as “Turtle Mountain” from the

Ojibway. He sent a request to the lieutenant governor of Manitoba for

his claim to be officially recognized.

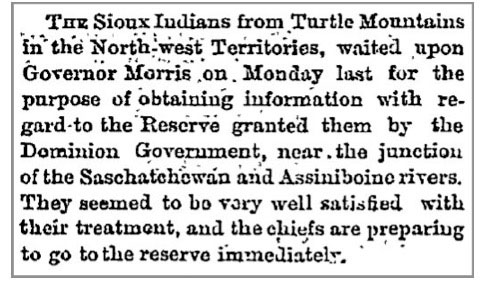

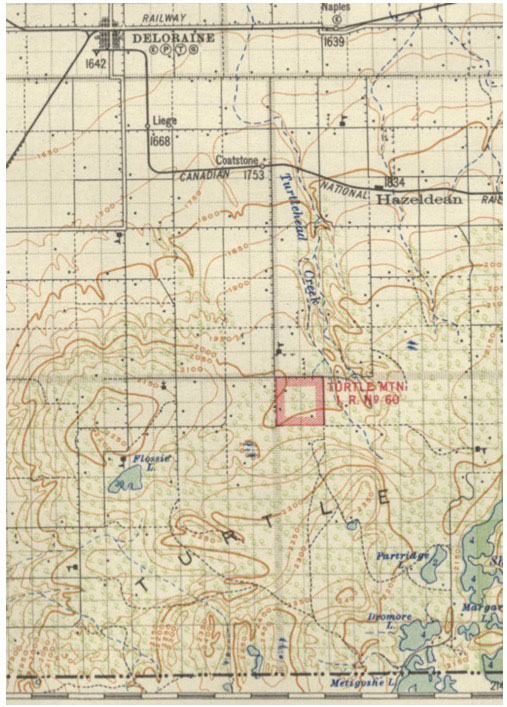

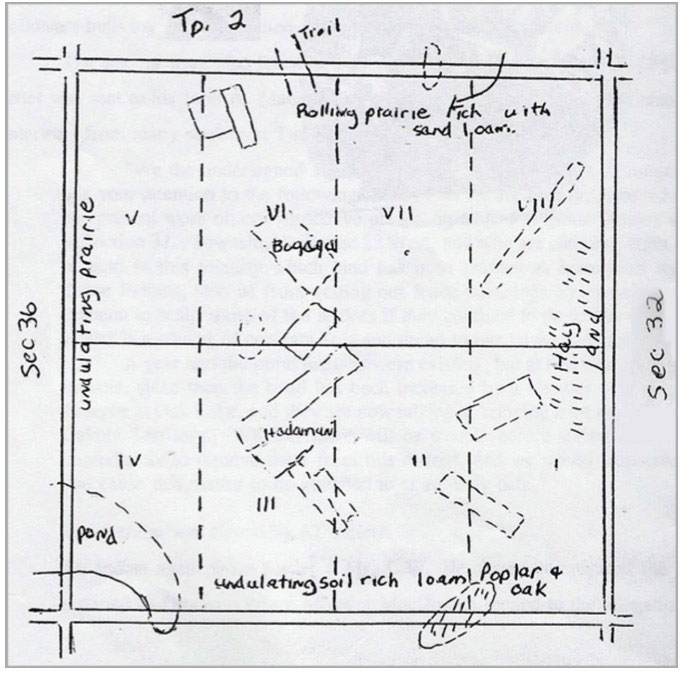

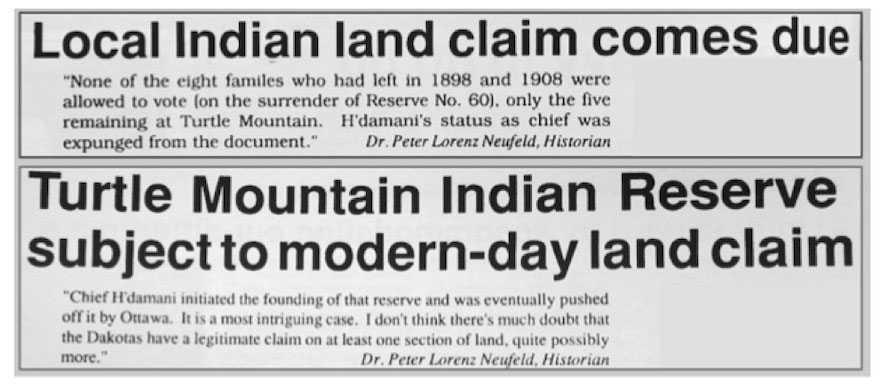

Lieutenant Governor Morris was not thrilled about giving land to H’damani’s group so near to the restless American border. Although the Dakota considered themselves to be residents and protectors of the entire North American Great Plains, the British did not recognize them as such or include them in any treaty with the Queen. But H’damani was determined to provide for his people. There were of course arguments against it. The policy had been to not establish a Dakota reserve so close to the U.S. border due to security concerns, but it was well known that H'damani was not involved in the battle at Little Big Horn. He and his people had arrived 14 years earlier - and posed no threat to American citizens. Further, to that the Dakota have been unwavering allies of Britain – during the American war of Independence, then through the 1812 troubles and to the present. It turned out that not all the Turtle Mtn. Dakota wanted to leave the area.  July 13, 1874 - The Nor'Wester In personal meetings with Morris, he explained that his people were struggling for survival as the buffalo herds dwindled. In addition to a piece of land, he asked for seed to plant, implements to help work the land, and some cattle. H'damani refused to move to the Oak Lake Reserve when it opened in 1877, so the government finally gave in and a single section (1 square mile) was designated as the Turtle Mountain Reserve . It became the smallest reserve in Canada. ‘Turtle Mountain Reserve’, was adapted from a story in Vantage Points 1.  The site of IR#60  The Reserve still appeared on maps from the 1920’s. The land’s proximity to Turtle Mountain offered H’damani’s band prime hunting and fishing opportunities. By 1884, they had succeeded in breaking 35 acres of land for farming using only one yoke of oxen. In that year the only outside assistance they received was a little seed and three bags of flour from the Canadian government.  A detailed Reserve Plan There are mixed accounts of how European settlers moving into the area regarded H'damani and his band. Local histories include comments such as: “The chief was a wise and good man, highly respected by all who knew him”. Other settlers were apparently unhappy. A group got together and wrote their grievances in a petition, complaining that the Dakota were hindering their access to timber, and in some cases threatening the settlers if they continued to go into the woods. When L.W. Herchmer, former Divisional Indian Agent was sent to investigate the concerns he reported that they were unfounded. It turned out that it was the settlers who were illegally taking wood. Herchmer’s investigation found the Turtle Mountain reserve was doing very well under the leadership of H'damani – having broken 35 acres with one yoke of oxen. They were building excellent houses and were keen to get along with their settler-neighbours. He emphasized in his report that many settlers do get on well with the Dakota. He also claimed that the Dakota were generally very well disposed towards the settlers, and wherever trouble has arisen it had, on all occasions, been directly attributable to the settlers. He did acknowledge that settlers in general had been spooked by events across the border and that some disliked seeing Indians in possession of desirable locations. Certainly not everyone opposed the presence of the reserve and many settlers got along quite well with their Dakota neighbours. Sources: Caldwell, Bob. Local History Curriculum. Chapter Three: The Sioux. Kroeker, Ben. Drawing the Line. Deloraine: DTS Publishing, 1993. Illustration: “2000-45-8.” Turtle Mountain Sioux Cemetery Records Fonds, Series III MG15 / D12. Boissevain Community Archives. Photo: Provincial Archives of Manitoba. Boundary Commissioner Photographs, 1872-74. An excerpt from a radio broadcast “The Turtle Mountain Reserve” by David Neufeld…. L.W.Herchmer here, former Divisional Indian Agent. I'm 73 now – remembering some interesting times - as Canada took over the west. In 1882, for example, I was asked by Sir John A himself to investigate a complaint around the Turtle Mountain Indian Reserve - IR60. I was stationed in Birtle, supervising Indian Agents on 13 reserves. What's an Indian Agent? He's a federal government appointed boss – for a reserve – always a non-indigenous man who controls most everything on the reserve. They hand out Treaty tokens - and - importantly, make sure reserve residents show their pass when leaving and returning - so as to know at all times how they interact with new settlers. My investigation found the Turtle Mountain reserve was doing very well under the leadership of H'damani – having broken 35 acres with one yoke of oxen. They were building excellent houses and were keen to get along with their settler-neighbours. The mountain offered them excellent hunting and fishing, so, other than a little seed and some flour, they received no government assistance. I emphasized in my report that many settlers do get on well with the Dakota. In my report, I made it clear that the Sioux are generally very well disposed towards the settlers, and wherever trouble has arisen it has, on all occasions, been directly attributable to the settlers. Settlers in general have been spooked by events across the border and, to be honest, dislike to see Indians in possession of desirable locations. The Prime Minister replied saying the Turtle Mountain Dakota should not be disturbed. But, even so, the reserve only lasted 30 years before it was “surrendered”. The reserve was too small (one square mile with 13 families) to warrant their own Indian Agent. And so government bureaucrats couldn't control the assimilation process of H'damani's people. Eventually the government paid IR60 residents $200 each to leave. Some went to Pipestone and some to Oak Lake. By 1909 only H'damani and his grandson remained. The government tried to auction the land, but no bids were offered. After a few years – with the tacit understanding that H'damani and his grandson could come and go as they pleased - it was finally sold. But not forgotten. While the Turtle Mountain – Souris Plains region has never been home to a residential school, the general mission of the residential schools program was somewhat evident in a short-lived effort to provide “education” for the small group of Dakota that lived on IR60* south of Deloraine in the 1890’s. The International Society of Christian Endeavor was an interdenominational organization for Protestant youth in Canada, Mexico, and the United States. In 1892 the Deloraine Branch published a short publication promoting the concept of a reserve school and soliciting funds. It begins with the reminder that although we have many church-run schools across the land, “it is a sad fact that we still have in Canada about 55,000 pagan Indians” and that we “as a Christian people” have an obligation to look after “the temporal and spiritual inter- ests of the Indians. First because we have taken their country.” The recognition that we have “taken” the livelihood of the people who rightfully owned the land is admirable, as the underlying as- sumption that European society and its traditions were in every way superior was an all-too- prevalent product of its time. The pamphlet goes on to re- mind us that the natives are living in poverty (of body and soul) while the Euro-settlers are swimming in wealth. Unfortunately their bias shows in their description of that poverty: “many of them are perish- ing in darkness and sin.” As we Canadians are begin- ning to acknowledge, some of the same assumptions were at the root of the residential schools disaster. It all started with some good, but often misguided, intentions. But even without abusive teachers, inadequate funds and chronic mis- management, the flawed concept was bound to fail. In 1892 the local Endeavor So-ciety obtained some funds and set up a school in a donated cabin on the reserve. Soon, with Rev. A.F. McKenzie and his wife in charge, classes were being held and a garden was being tended by children. They were learning hymns. A night school for young adults was in operation. Neighbouring communities were taking note.  The Deloraine group seems to have taken a leadership position in promoting the idea of on-reserve day schools. A Central Committee was formed in Deloraine in 1894 to “extend the work,” with the goal of “reaching all the neglected bands in the Province...” The views expressed in the promotional pamphlet display both an understanding of the root of the plight of Indigenous Peoples and an all-too-familiar paternalism and European bias.  While we can take comfort in the fact that they recognized that “The Indians have the same capabilities, the same emotions and aspirations, sorrows and hopes as we have...” we now know that the prescription for “civilizing” them was neither appropriate nor workable. The good news is that Aboriginal cultures have survived, and in this case, some good may well have come out of the local effort. It seems the school was short lived and that the local Indian agent preferred not to support it. In fact he advocated for closing the re- serve and therefore was against any efforts to establish a viable community. He wanted students to attend the residential school in Regina. Without the support of Indian Affairs, the school faced bankruptcy and closed. Sources: Central Committee. “An Appeal to the Christian Endeavor Societies, Epworth leagues of Christian Endeavor, and the Christian peo- ple of Manitoba. In behalf of our Suffering Indians.” Boissevain Library & Archives Oral History Collection. Deloraine. 1894. The Deloraine branch of the Chris- tian Endeavor Society solicited funds for the Mission School on IR #60 In 1889 Indian Agent J.A. Markle, based in Birtle, raised the possibility of relocating H’damani’s band. He claimed that because the Turtle Mountain location was remote, it didn’t lend itself to “supervision.” The proximity to the US border was also considered to be a problem. The superintendent general agreed and noted that they should be moved to a location “where they would be looked after properly.” Slowly, families did decide to relocate, some encouraged by a $200 government pay-off. By 1909, only H’damani, his grandson Chaske (later known as Sitting Eagle) and a few others remained. The government then ignored H’damani’s authority and convinced the remaining families to sign a release for the reserve, and the land was eventually sold by public auction in 1911. The reserve officially ceased to exist. On November 21st, 1913, H’damani and his remaining family were paid a small token—nowhere near the amount that the land was worth—and instructed to remove themselves. H'damani's grandson, Sitting Eagle, lived out the last dozen years of his life in a small log cabin in the northwest corner of the former reserve. He died there alone in April of 1944 and is buried in an unmarked grave in the Deloraine Cemetery. For the next two decades Indian Affairs and their agents did everything in their power to close IR60 and H’Damani and his follow- ers resisted. In the end Indian Af- fairs prevailed and IR60 was closed in 1913. On May 11, 2000, the Canupawakpa Dakota First Nation requested that the Indian Claims Commission hold an inquiry into the Turtle Mountain IR60 surrender. The Canupawakpa Reserve is home to descendants of H’damani’s band, and they were supported in their claim by the Sioux Valley Dakota First Nation. In short, the Canupawakpa claim was that H’damani and his band were improperly forced out of their home and not fairly compensated.  Dr. Peter Lorenz Neufeld grew up in the Whitewater area. In 1992 The Deloraine Times & Star published a detailed report about the Turtle Mountain Reserve and the related land claims. The report is available at www.vantagepoints.ca The commission reviewed the history of the Dakota and examined the Canupawakpa contention that Indian Affairs had manipulated the process by which band members voted - they had selectively conferred eligibility on some and not on others, based on improper evidence of residency. They reviewed evidence of mismanagement and bad faith by Indian Affairs and its agents. In 2003 The Indian Claims Commission issued their report. They concluded that: “Turtle Mountain IR60 was validly surrendered in accordance with the pro- visions of the Indian Act and that Canada, as fiduciary in taking this surrender, conducted itself as a reasonable and prudent trustee.” In effect...they followed the rules that existed at the time. They don’t seem to have ad- dressed the real issue, that the rules themselves were the problem. The board did recommend that the “Government of Canada recognize the historical connection of the descendants of the Turtle Mountain Band to the lands once occupied by Turtle Mountain IR60 and, in particular, the lands taken up by the burial of their an- cestors.” They further recommended that the Government of Canada acquire an appropriate part of the lands once taken up as Turtle Mountain IR60, to be suitably designated and recognized for the important ancestral burial ground that it is. The Residents On March 8, 1898, Indian Agent Markle wrote to the Indian Commissioner that two families living on Turtle Mountain (likely Iyo-jan-jan and Widow Kasto) had agreed to move to the Oak Lake reserve if the Department of Indian Affairs would erect dwellings for them in their new location. Markle also mentioned that during the attempts to relocate the Band to Moose Mountain, a similar “inducement” was authorized by the department. On May 24, 1898, Markle reported that three families (Iyo-jan-jan, Widow Kasto, and Kibana Hota) had moved from Turtle Mountain to the Oak Lake reserve. He included an additional request from Kibana Hota for a sum of $40 to help in constructing his new home. Widow Kasto also requested the reservation of two small parcels of land at the Turtle Mountain IR 60 site for a burial plot. Hinhansunna, filled in an Application for admission into Oak Lake Band #59, so did George Nayioza, also Sam Eagle #10, likewise, John Matoita #12. The Applications were dated August 3rd 1908. A fifth male member, Mahtohkita, of Turtle Mountain petitioned on September 16, 1908, to become a member of Oak Lake. On March 11, 1909, he again visited the reserve and found that two members, Bogaga and Tetunkanopa, had “declared their desire to surrender the reserve lands; whilst the third, Hdamani #1, wishes to hear direct from you.” Three people (Bogaga, Tetunkanopa, and his son Charlie Tetunkanopa) voted in favour of the surrender of the Turtle Mountain reserve. Two people (H’damani and his grandson Chaske) voted against surrender. Why Turtle Mountain Was Important There were many reasons why H’damani resisted moving. To them the Turtle Mountain location offered security and continuity. The wooded hilly area had been a wintering place long before the Reserve was established. It was home. It offered wood for heat, water, medicines; everything was there for a good camp. How important was it that it was right beside their neighbours, because the boundary was pretty invisible yet, your relatives were just across the line, so to speak. Of course, the Government claimed that the nearness presented a security concern, despite the fact that there had never been a problem, It appears that the real issue for the Government and the Indian Agent was one of control and convenience for them. They saw the small reserve as inefficient. Another issue was that it was quite it far from the Indian agent. Sources: Budd, Brian. “Unist’ot’en and the limits of recon- ciliation in Canada.” The Conversation. 2019. http://theconversation.com/ unistoten-and-the-limits-of-reconciliation- in-canada-109704. Newspaper Clippings: Nor’wester. Winnipeg. Nov 21, 1864. The Deloraine Time and Star. Deloraine. Jan 22, 1992. Photo: Teyana Neufeld |