by Harry Baker Brehaut, P. Eng.

MHS Transactions, Series 3, Number 28, 1971-72 season

|

The earliest form of transportation in the West, aside from the Indian travois was by water which was followed by a vehicle for travel by land. In fact the first entry into the territory now known as Manitoba was made by sea, by way of Hudson Bay in 1612, by Admiral Sir Thomas Button, [1] a Welshman, who named Port Nelson and spent the winter of 1612-13 there.

In succeeding years with the gradual exploration of the territory it was found that it contained a wealth of fur-bearing animals, whose fur was in great demand in European countries. This led to the development of the fur trade enterprise in the vast western territory. Toward the end of the seventeenth century and during the eighteenth century, there was great expansion in the trade. [2]

The eastern traders, later organized as the North West Company, from the area of the St. Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers pushed westward along the Great Lakes to Grand Portage on Lake Superior and westward across the prairies. The Hudson’s Bay Company was formed in 1670 with the charter granted by Charles II to “The Governors and Company of Adventurers Trading into Hudson’s Bay." York boats struggled up the Hayes River from York Factory at Port Nelson, to Norway House at the northern end of Lake Winnipeg.

From Norway House boats skirted the north shore of Lake Winnipeg to Grand Rapids, which provided access to the great Saskatchewan River system and its tributaries west to the Rocky Mountains. Boats plied southward along the eastern shore of Lake Winnipeg to the territory of the Red River and its principal tributary the Assiniboine, at which confluence Fort Garry was established.

From Fort Churchill, at the estuary of the Churchill River, [3] efforts were made to establish a route up the Churchill but they proved impracticable. Later however a route was followed from Cumberland Lake north to the Churchill River and thence west across the La Loche-Methye Portage, which provided access to the fur wealth of the great Athabasca and Northern Districts. Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca was nearly 1500 miles from York Factory and about 3000 miles from Lachine. Eventually the trade penetrated to the Pacific Coast down the Columbia River and ships sailed around Cape Horn to Fort Astoria at the estuary of the Columbia.

To the south communication was secured from Fort Garry up the Red River which connected with the Minnesota River whose confluence with the Mississippi River at Fort Snelling, gave entrance to the great Mississippi River system and its outlet on the Gulf of Mexico. Overland contact was made southward with the head-waters of the extensive Missouri River system. The fur trade was thus established across the continent of North America with outlets on the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and tidewater on the Hudson Bay and the Gulf of Mexico.

The great area named Rupert’s Land by Charles II, after his cousin Prince Rupert, included nearly all of what is now Canada and also reached into present day United States territory.

As the trade penetrated inland in the west, the need for a vehicle of land transportation became imperative and a cart came into being which was peculiarly suited to the needs of the fur trade, the terrain and the environment. Such a cart made its appearance in 1801 at Pembina Post of the North West Company, which was the forerunner of the famous Red River Cart.

The development of the cart is described in the account which follows and the accompanying complementary map [4] shows the principal trails it made across the prairies. The cart trails are designated by numerals and the main water routes by letters of the alphabet.

Alexander Henry, the Younger, located Pembina Post at the confluence of the Pembina and Red Rivers. He was a North West Company trader from Montreal who came west on the Lake Superior route.

On 19 July 1800 Henry left Grand Portage on Lake Superior for the Red River. He travelled by “canot du nord" along the fur trader route’ up the Pigeon River to Bas de la Riviere on Lake Winnipeg. Particulars of this route are given on sheet 5 in the section, ‘Grand Portage-Bas de la Riviere Route’.

From Bas de la Riviere (Fort Alexander) he crossed over the shallow strait between Elk Island and Victoria Beach and continued along the south shore of Lake Winnipeg to the mouth of the Red River. He proceeded up the Red, until on August 18th he reached the ‘Forks’ (Fort Garry) of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers.

At the ‘Forks’ he divided his party and sent half of it up the Assiniboine and took the remainder up the Red. Henry experienced difficulty with some of his men, who did not wish to go too far south because of fear of the Sioux Indians. He managed however to reach Park River where it joins the Red, about 35 miles south of the present town of Pembina on September 8. Here he built a temporary post.

In May, 1801, he started to build a permanent post at the confluence of the Pembina and Red Rivers, which he completed in October of the same year. This was the Pembina Post where the first cart was made and the accompanying map shows its location.

This is about 65 miles south of Winnipeg and at that time was in the old realm of Rupert’s Land, granted to the Hudson’s Bay Company by Charles II. Later when the International Boundary between Canada and the United States, was established at the 49° parallel, it became United States territory.

In the unrecorded history of our primitive ancestors a new device was found in the wheel. No one knows who discovered it and authoritative sources estimate it was about five thousand years ago. The Indians had the travois, but did not have the wheel. Since there would have been no trail without the cart and no cart without the wheel, reference to the wheel is relevant as it not only made possible the development of our civilization but also the opening up of our western plains.

We may speculate how the wheel came about. Possibly one day aeons of years ago, a tree trunk denuded of branches rolled down a hillside. An imaginative prehistoric man watching it realized that a short length of tree trunk could be made to roll by hand wherever required. Later perhaps this round slice of tree trunk with a short stick driven through a hole in its center, which we would call an axle, could be used as a crude sort of foot wheel. In time it is conceivable two round slices of tree trunk would be joined together by a short pole and there would be born the cart, the vehicle of land transportation.

The two wheeled cart was used in Europe, Asia and Africa millenia ago and it was indispensable in the opening up of our vast Canadian prairies. Its advent into the Red River Valley relatively near the junction of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers made it peculiarly a vehicle adapted to this area and it has become a symbol of the pioneer era of Manitoba. Water transportation by canoe or boat served the purpose as long as activities were relatively close to river or lake, but as man pushed farther and farther inland, this mode of transport became greatly limited, and in many situations difficult enough, to make land transportation preferable. Other factors militating against water transportation were: the conveyance of the spoils of the buffalo hunts, the great increase in the fur trade and the establishment of inland trading posts. Man’s back, the pack horse or the Indian travois could no longer cope with these conditions and during the nineteenth century it appears the cart became one of the chief means of land transportation on the prairies, until superseded by the steamboat and the railroad.

The pioneers of Manitoba were either too busy or it did not occur to them to leave an adequate record of the early development of the cart. Consequently what little information is available must be gleaned from later scattered references, in which the cart is mentioned incidentally and not as a prime consideration. It was left for a busy fur trader, Alexander Henry, the Younger, who kept a daily journal, to record the first and only information as far as is known about the cart. He relates the making and putting the cart into service at Pembina Post.

In the fall of 1801 the first cart [6] appeared with solid wheels “sawed off from the ends of logs whose diameter was three feet." These would be similar to the prototype heretofore mentioned. In the fall of 1802 “a new sort of cart was made having four perpendicular spokes without the least bending outward." In the spring of 1803 a further improved cart was put into use, “having a real pair of wheels on the plan of those in Canada." These were probably ‘dished’ wheels but Henry does not mention it. This was the beginning of the cart later to be called the Red River Cart.

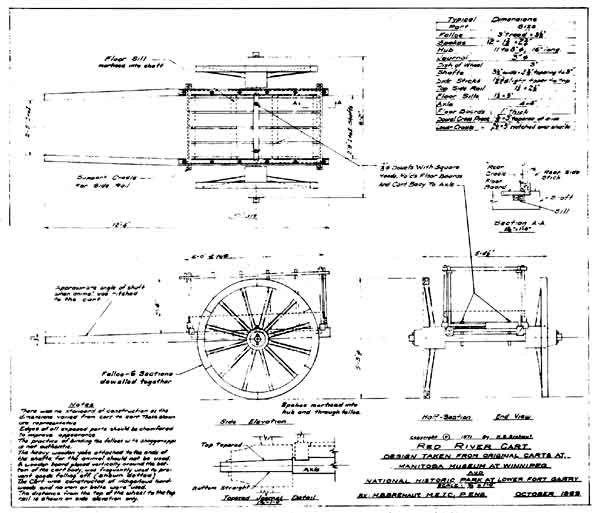

There was a general type of cart but no standard of construction. Measurements taken from existing old carts vary as to dimensions and sizes of parts. The wheel diameters were not the same. The number of spokes varied. The shafts were either straight and converging, or bent to bring them closer together at the animal’s collar. A stick or a cradle was used to support the ends of the side rails. A board was usually placed vertically on the floor along the side sticks and across the ends to prevent anything slipping off, but in hauling packs of ninety pounds called ‘pieces’, they were probably large enough for the side sticks to hold them in the cart.

The cart body including shafts might be dowelled to the axle or in another design the cart body and shafts would be secured to the axle by two long trunnels, one on each side. The lower stick of the cradles at each end of the cart body was recessed to receive the ends of the floor boards, to prevent them moving lengthwise. On top of the floor boards a cross piece was placed directly over the axle and rested on the shafts. A long trunnel through this cross piece and the center of the floor board adjacent to the shaft, passed through the axle and thus secured the cart body and shafts to the undercarriage of the cart. This facilitated, not only renewal of broken floor boards but also the replacement of a broken axle, by permitting the removal of the cart body and shafts from the undercarriage and a new axle installed.

The journal of the axle and the hole in the hub were tapered toward the outside away from the cart body. There was however a difference in the manner of tapering them. [7] The hole in the hub was tapered concentrically from both ends. The journal was tapered on the top but was straight on the bottom, while on the sides the taper was equalized. This rather ingenuous design was used for several reasons. It equalized the stress on the dished wheel and together with the equalized taper on the sides of the axle, permitted the felloe to sit level on the ground and the wheel to travel in a straight line on the trail. It also increased the size of the axle at its weakest point where the change in cross-section is made from circular to rectangular.

The ‘dished’ wheel was an important development in the cart. The ‘dish’ was made by inclining the spokes outward from the cart body. The amount of the dish varied but was about 3 inches. It gave the cart better stability by preventing tipping on rough terrain and facilitated getting out when stuck in the mud. The dished wheel was also used as a raft when crossing rivers, by removing the wheels and lashing them together concave side upward. Then the cart body and cargo were placed upon them and ferried across the water.

Saplings bent in the form of a semi-circle and attached to the side railings of the cart, provided a frame to which a covering of hides or canvas was attached, as a shield from the sun or weather. The carts were not only used as a conveyance but also as a shelter, a defence in case of attack or a barrier for an encampment.

The drawing of the general arrangement of the cart, [8] shows the typical dimensions: the wheel 5'-3" diameter; cart body 3' by 5 or 6' long; height ground to floor about 3'; height floor to side rail about 2'-4"; length about 12'-4". After the original solid wheels, the number of spokes varied from four to sixteen. The old cart at Lower Fort Garry National Historic Park has eleven spokes. The old cart in the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature has twelve. Near Borden, Saskatchewan on Yellowhead Highway No. 5, a glasses in site panel has photographs of old carts having fourteen and sixteen spokes. Research has established that twelve spokes were the most prevalent. The weight of the cart was approximately 550 pounds and the load capacity in the neighbourhood of 500 pounds when drawn by a horse for faster travel.

The cart was made of indigenous hardwoods whenever available. The hubs were elm. Oak was used for the axle and shafts, spokes and felloes with ash for the side sticks. Other woods were no doubt used when these were not available. No metal of any kind was used in its construction. Only the simplest tools were used to build it—hand-axe, small saw, draw-knife and screw-auger. It is of interest that these tools and a chisel were found at Duck Lake, Saskatchewan in 1955. [9]

Repairs when required could readily be made on the trail where wood was available. When the dowel, connecting two sections of the felloe broke, two flat pieces of wood were cut to conform to the wheel curvature, and one piece was placed on each side of the felloe at the joint requiring repair and bound together with strips of animal hide, wound crosswise around the felloe, usually referred to as shagganappe, which had been soaked in water. When the strips dried they held the curved flat wooden boards firmly against the felloe and enabled the cart to travel to the nearest post where permanent repairs could be made.

It appears that the repair of a felloe section with strips of hide encouraged the idea, that the entire felloe was bound all the way around in this manner, and it is alleged that some Indians used this practice. Best informed opinion rejects this as being incorrect. There is however some evidence from early accounts, that a rawhide tire was used in some instances on the wheel of the cart. [10] It ran all the way around on the rim of felloe of the wheel on the tread and folded over on the sides, and tied with thongs between the spokes. It was put on ‘green’ or wet and when it dried shrank and held in place so tightly, that it never came off but lasted as long as the cart held together. There is an old Red River cart in the museum at North Battleford, Saskatchewan, equipped with these tires.

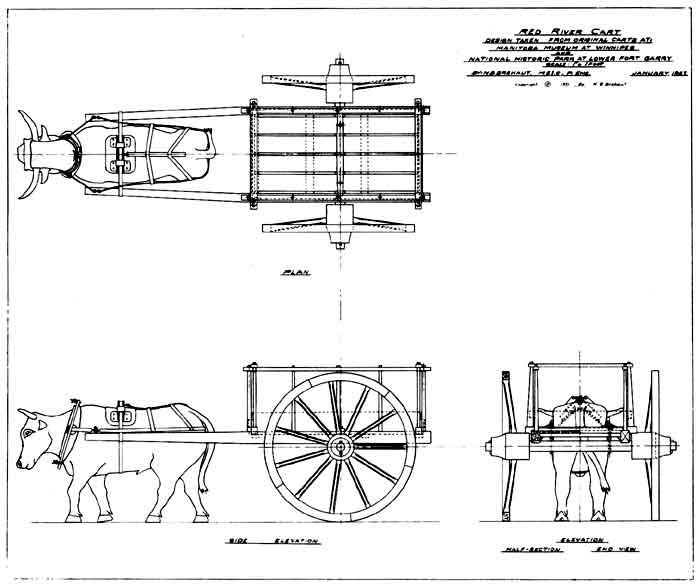

The harness for the animal pulling the cart was made from hides. The first carts were drawn by one horse. The hames and collar were used for both the horse and later on for the ox. The shafts were connected to the hames by a short trace called a ‘tug’. A rectangular hole was made in the hames to permit the tug when folded over to go through it, after which the loop in the tug was opened out and a wooden key was placed in it. Then the tug was pulled to bring the key firmly against the hames. The other end of the tug, was secured to a dowel, or later metal hook, near the end of the shaft. From this dowel a check-strap went around the animal’s rump, to a similar connection at the end of the other shaft. Straps over the animal’s back held this in place. Behind the animal’s shoulder the ‘clobber’ was located and was grooved to receive the belly-band and the strap which was attached to each shaft to support them. These are shown on the one twelfth size model of the cart, ox and harness.

Alexander Henry stated he had several carts drawn by two horses in 1803, [11] the same year in which he produced his improved cart with a real pair of wheels. It would be unrealistic to expect that simultaneously with building an improved one-horse cart, he made a cart for a team of horses. Two ponies were used in a Red River Cart on a trip by John Schultz in 1860. [12] In these instances it is possible that some sort of a tandem hitch for two horses to the cart was used, when a heavy load was to be hauled or speed was not essential. Such a tandem arrangement was used in 1868 by Walter Traill, [13] when he was stationed at Fort Ellice.

There is no picture of the two horse cart, but numerous photographs are on the record, of the cart with two shafts for one animal. We know the Red River Cart had two shafts, consequently we conclude it was pulled under normal conditions of trail transportation by one animal.

The heavy cumbersome yoke [14] which is popularly associated with the cart is a practice which should not be used. The fact is the heavy yoke was designed for a team of oxen and was rarely if ever used with a single ox. [15] Wooden collars are known to have been used for single animals. These were elliptical in shape and fitted around the neck of the animal like a hames and collar, but there was no resemblance to the heavy impracticable yoke. At all events it was part of the harness and not the cart.

The formation of the carts on the trail, aside from local freighting, was in ‘brigades’ or ‘trains’. A brigade consisted of ten carts, while a train was a procession of carts up to two miles or more in length. There were three drivers to every group of ten carts and an overseer, who attended to everything necessary to keep the outfit moving, including the supply of animals and the repair of the carts. In hostile country it was the practice for several carts to travel abreast, to prevent an attack being made on the rear. At the head of the procession the guide walked beside the leading ox and each ox was tied at its head to the rear of the cart in front. The rate of travel was about two miles per hour or approximately twenty to twenty-five miles in a day maximum. If faster travel was required horses were substituted for oxen and a large supply of these animals was maintained at the principal posts. They were also available to replace animals which had suffered injury or otherwise rendered incapable of travelling.

According to early accounts the cart was a most unimposing looking vehicle and wonder was often expressed, by those unfamiliar with it, that such a rickety looking contraption could stand up under the rigorous conditions encountered on the trail. When loaded it gave forth a blood-curdling squeal which could be heard for miles and which came to be associated with it. This squeal was caused by the friction of the dry wood of the hub of the wheel turning on the axle and could not be eliminated.

If grease was used the dust of the trail would mix with the grease and wear down the axle or congeal and prevent the wheel from turning. Notwithstanding the cart not only held together but performed a prodigious job of transport and in a unique way seemed peculiarly adapted for the terrain and conditions under which it was used. The crude cart with solid wheels had become the famous Red River Cart.

The two great rivals in the fur trade, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company, entered the western territory by two different routes. The Hudson’s Bay Company via Port Nelson (York Factory) on Hudson Bay, and the North West Company via Grand Portage on Lake Superior, the former on tide-water and the latter on the Great Lakes. Their penetration inland was determined by these points and their expansion was based on the main water transportation which followed as a result.

The Hudson’s Bay Company’s main arterial route ran from York Factory to Norway House and along Lake Winnipeg to the Red River. It skirted the eastern shore of the lake to the ‘Narrows’, where it crossed over to the western shore to the Red River. The other main route was from Norway House along the northern shore of Lake Winnipeg to Grand Rapids at the mouth of the Saskatchewan, west to Cumberland House, Carlton House and on to Edmonton, a distance of nearly 1500 miles.

The North West Company’s trunk route ran from Grand Portage to Bas de la Riviere and north along the eastern shore of Lake Winnipeg to the ‘Narrows’, where it crossed over to the western shore to Grand Rapids, and thence west to Cumberland Lake. Here it turned north to Frog Portage on the English-Churchill River, then west to lle-a-la-Crosse, across La Loche-Methye Portage to the Athabasca. Another trunk route was from Bas de la Riviere to Red River.

Furs and supplies were fed into the main routes and there were in some areas minor but important alternative routes.

It is of interest to note that in the far flung activities of these two rival companies their paths, as far as these main trunk routes were concerned, coincided only at two places. One of these was for a relatively short distance at the ‘Narrows’ on Lake Winnipeg and the other from Grand Rapids up the Saskatchewan to Cumberland Lake, a total distance of approximately 225 miles.

The York boat of the Hudson’s Bay Company manned by Orkneymen plied the Hayes and Lake Winnipeg. On these and all the larger prairie rivers, sail was spread whenever weather conditions permitted. It was about 40 to 45 feet long, with 9'-6" to 10'-6" beam, flat bottom and shallow draft of about 1'-6". It was heavily built with long, sloping stem and stem posts and lasted about 3 years. It had a crew of from 8-15 oarsmen, depending on the load capacity of from 3 to 4 tons. [16]

‘Canot de Maitre’, the large canoe was used by the North West Company on the ‘voyageur’ route across the Great Lakes to Grand Portage, its western terminus. It was about 36 feet long and manned by 8-10 voyageurs, and a cargo capacity of approximately 6000 pounds. From Grand Portage inland the ‘canot du nord’ was put into service. It had a length of 20-25 feet, five or six paddlers and about half the cargo capacity of the ‘canot du maitre’. Later the North West Company used sailing vessels on Lake Superior and steam boats operated for a limited period and under restricted conditions on the Red, Assiniboine and Saskatchewan River system.

In 1612 Thomas Button in the ‘Resolution’ sailed across the North Atlantic Ocean, through Hudson Strait into Hudson Bay. He skirted along the north and western shore of the bay, searching for a passage to the western sea and a route to the Orient. Instead he found the mouth of a river, which he named Nelson as a memoriam to his sailing master who died there. Over half a century elapsed before the Hudson’s Bay Company’s ship the ‘Nonsuch’ [17] sailed into the bay, not on a quest for a route to the western sea but rather to trade. This was the genesis of the fur trade on a commercial basis in the west.

The mouth of the Hayes River is separated from the estuary of the Nelson River by a peninsula on which York Factory was located. The Hayes River was the main artery of transport from York Factory to Norway House, at the north east end of Lake Winnipeg, a distance of about 350 miles. It was chosen rather than the Nelson because it was easier to navigate.

The route from Warren Landing on Lake Winnipeg led across Playgreen Lake to Norway House, on the eastern branch of the Nelson, along the Echimamish River at the height of land, then through Lakes Robinson, Logan, Windy and Oxford, at whose eastern end Oxford House was located. It continued across Knee and Swampy Lakes and down the river to York Factory. It was a torturous route with many portages along which the crews manned the heavy York boats. An attempt to avoid it by building a roadway never materialized.

From Norway House the boats skirted along the treacherous north shore of Lake Winnipeg to Grand Rapids at the mouth of the Saskatchewan River. Thence the route continued up the Saskatchewan to Cumberland House on Cumberland Lake, a distance of about 200 miles. From there it continued west to Carlton House and on to Edmonton (Upper Fort des Prairies) a total distance from Norway House of approximately 1000 miles. Cumberland House established in 1774, was the first inland post on the prairies of the Hudson’s Bay Company. It is the oldest settlement in Saskatchewan and was a cardinal point of water transportation and controlled not only the Saskatchewan territory but also the approach, via the Sturgeon-Weir River to the English-Churchill River and entrance into the Athabasca territory.

This was a main trunk route of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Leaving Norway House the boats kept close to the eastern shore of Lake Winnipeg because of navigational hazards on this lake. In the ‘Narrows’ they normally took the route between Hecla Island and the western shore, although the channel between Hecla and Black Islands, was no doubt used. It was in this area that the Hudson’s Bay and North West Companies’ routes crossed.

At the mouth of the Red River the route led up to its confluence with the Assiniboine at Fort Rouge and Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg), a distance of about 325 miles from Norway House. This provided access to the territory at the headwaters of the Assiniboine and Qu’Appelle Rivers.

The route from Lachine [18] was the main inland water transportation line to the west at Grand Portage, south west of the then community of Fort William, now the city of Thunder Bay, on the western shore of Lake Superior.

Leaving Lachine it led up the Ottawa River, past Calumet and Des Joachim’s portages, and thence along the Mattawa, Lake Nipissing and French River to Georgian Bay. It then proceeded through the north channel of Lake Huron to Sault Ste. Marie, about 750 miles distant from Lachine. From Sault Ste. Marie the course skirted, for safe navigation, the northern shore of Lake Superior to Grand Portage. The distance from Sault Ste. Marie to Thunder Bay is in the vicinity of 450 miles, thus making the route approximately 1200 miles long.

Victualing the voyageurs of the canots de maitre on this route was of paramount importance, as it had to be provided for and carried with them, during the long trip through primitive wilderness. The strenuous work of these courageous men from dawn to sunset required highly nutritious food, which could be carried in a minimum of space. This was found in what they called ‘hominy’ made of ground corn or rice, mixed with fat. This was supplemented with beans and pork.

Grand Portage was located approximately 38 miles southwest of Fort William and about 10 miles south of the mouth of the Pigeon River on Lake Superior. Because of ’falls’ Pigeon River was un-navigable for several miles up from its discharge into Lake Superior.

The old Indian trail, to avoid this un-navigable stretch, portaged across some 9 miles to the river where Fort Charlotte was located. The trail then followed Pigeon River up to Mountain Lake and then crossed to Arrow Lake, over what was a long and difficult portage and continued on to Rose Lake.

The fur traders eliminated this portage across to Arrow Lake by making a route of their own, one of the rare occasions they did so. They followed Mountain Lake, crossed Watap portage to Watap Lake, thence to Rove Lake and along the rough portage to Rose Lake.

From Rose Lake the course crossed the height of land between North and South Lakes and continued on across Basswood and Crooked Lakes to Lac la Croix. There were 29 portages totaling 15 miles from Grand Portage to Lac la Croix.

The drainage between the height of land and Arrow Lake is extremely complicated. South Lake does not flow directly into Pigeon River but into Arrow Lake and Arrow River, a tributary of the Pigeon, which it joins several miles above its mouth.

From Lac la Croix the route followed Namakan and Rainy Lakes to Lake of the Woods. Up to this point the course follows the International Boundary, except for a short distance at Grand Portage. After Lake of the Woods the route follows the Winnipeg River to Bas de la Riviere (Fort Alexander) on Lake Winnipeg. This was the fur traders’ route followed by Alexander Henry, the Younger, on his trip to Red River in 1800, and was in use until 1802. This route was about 500 miles in length.

When the United States levied duties at Grand Portage, the headquarters were changed to Fort William and the Kaministikwia-Dog Lake route was adopted. This was the revival of an old route.

It was travelled in 1688 by de Noyen and was the original route of the fur traders from Lake Superior. It was discontinued when La Verendrye found the old Indian Grand Portage route which was easier and shorter by some 80 miles. Just before the Americans imposed levies at Grand Portage, Roderic Mackenzie re-explored the Kaministikwia Route and after 1803 the canoes of the fur traders plied it until modern transportation displaced them.

Leaving Fort William, Kakabeka Falls was avoided by Mountain portage. Thence the route turns north along the Kaministikwia River through Dog Lake and along Dog River, to Lac des Mille Lacs, across Pickerel Lake and down Maligne River to Lac la Croix which was probably so named because of the crossing of the two routes. From Lac la Croix it followed the same route as the Grand Portage-Bas de la Riviere route to Lake Winnipeg. The distance from Fort William to Lac la Croix by this route was approximately 230 miles, as compared to about 150 miles from Grand Portage.

The Churchill River whose estuary was at Fort Churchill on Hudson Bay, was known as the English River in its upper reaches. It occupied a unique position because it provided the only serviceable commercial trunk route to Athabasca and the North West.

After the military struggles in the 18th century with the French had ended the English had gained control of the territory and great expansion took place in the fur trade. The Hudson’s Bay Company had built their posts on tidewater on Hudson Bay and their ‘modus operandi’ at least during this period, required the Indians to bring their furs to them. This was in contrast to the Montrealers, later organized as the North West Company, policy of establishing inland posts relatively close to the trapping areas.

The Athabasca region was the great prize of fur wealth. The North West Company had penetrated to the shores of Lake Athabasca, where they built Fort Chipewyan, their first post in 1788. The Hudson’s Bay Company did not establish Nottingham House, their first post there until 1802, which was superseded in 1815 by Fort Wedderham only a short distance from Fort Chipewyan the post of their rival.

Before their entry into Athabasca the Hudson’s Bay Company’s returns came largely from the Saskatchewan River territory and passed through Cumberland Lake to the Bay. After the opening up of the Athabasca area Fort Churchill became a focal point of trade rivalry. The trade came mainly by the English-Churchill River from Athabasca to Churchill and York Factory. The Hudson’s Bay Company had built a post at York Factory in 1682 and at Fort Churchill in 1688. When the latter was destroyed by fire it was rebuilt in 1717 chiefly to enable the Chipewyan Indians to bring their furs to Churchill unmolested. It was a long and arduous route dominated most of the way by the North West Company and the season of open water was considerably shorter than the southern route.

There were five principal routes or variations of them in this area used by the Indian ‘middle-men’ or ‘coureur de bois’ to bring their pelts to Churchill and York Factory: The Churchill River. The Grass River to Split Lake on the Nelson, which was also known as the ‘upper’ or ‘north’ track. The Minago River to Cross Lake on the Nelson and along Bigstone River to the Hayes River called the ‘middle’ track, which had a branch from Cross Lake to Oxford Lake on the Hayes. The Burntwood River to Split Lake on the Nelson, and the Hayes River from York Factory through Norway House and across the north end of Lake Winnipeg to Cumberland Lake.

The Hudson’s Bay Company was seriously harassed by their rival having the upper hand on the rivers flowing into the Hudson Bay which enabled the North West Company to relieve, by persuasion or force, the Indians and traders of their furs destined to their posts on tidewater. To cope with this the Company organized Inland Trading Expeditions and eventually built Inland Posts. This brought about direct confrontation and was something more serious than intercepting the shipments and resulted in an internecine struggle involving sabotage, plunder and violence, particularly on the English-Churchill and Sturgeon-Weir Rivers and the Saskatchewan River from Cumberland Lake to Grand Rapids.

The great swing southward from the English-Churchill along the Sturgeon-Weir to Cumberland Lake and thence northeast again to reach Churchill and York Factory impelled the Hudson’s Bay Company to search for a more direct and shorter route to these ports.

The Hudson’s Bay Company in the quest for a shorter route employed the foremost explorers and traders to investigate every possible alternative over a period of several decades. The Seal River was explored by Peter Fidler in 1793 from its mouth on Hudson Bay but shallow water would have necessitated the use of flat-bottomed boats with sloping stem and stern, which idea led to the development of the York Boat. The Churchill River was explored from its estuary but nothing developed from it. A seaborne expedition went north on Hudson Bay in the hope of finding a communication if possible in the vicinity of Chesterfield Inlet, between Fort Churchill and Lake Athabasca but nothing came of it. The Nelson River was used as an inland route up to Split Lake and Lake Winnipeg. However in windy weather it entailed a hazardous course in rounding Point au Marsh on the open sea, from York Factory to Port Nelson. Also the high volume of water on the Nelson was a deterrent. A route was tried up the Beaver River from Lac Ile a la Crosse across Lac la Biche to the Athabasca but nothing came of it. David Thompson explored the Reindeer River from its confluence with the English-Churchill to Reindeer Lake, across Wollaston Lake and along Fond du Lac River to the eastern shore of Lake Athabasca. He encountered great hardships and the route was considered too difficult and dangerous.

The Burntwood River route was very favorably considered by Governor George Simpson who with the approval of the Hudson’s Bay Company Committee [19] in London had it examined. The report was so satisfactory that Simpson ordered the returns from Athabasca to use it in 1822-1823, by way of Nelson River, Split Lake, Nelson Lake and the Burntwood Carrying Place to Frog Portage.

The Carrying Place [20] was a portage between the drainage of the Nelson and English-Churchill Rivers, from the north end of Burntwood Lake to the south end of present day Flatrock Lake. [21]

In 1824 Simpson tried the route but not having a guide who knew the way to Frog Portage he left the route and went over a difficult portage to Nelson House [22] on Nelson Lake, Churchill River, to find one. From there he proceeded to Frog Portage. His interest in the route cooled and he decided it was impracticable because of several factors which included the short season of open water and the remoteness of the pemmican supply. In 1828 when he started from York Factory for Peace River he took the Hayes River-Cumberland Lake route and shortly thereafter the Burntwood River route was abandoned. If it had been successful it would have saved an estimated 200 miles on the trip to Athabasca.

Finally, after about half a century on and off, of search, the Hudson’s Bay Company was unable to find an alternative satisfactory fur trade route. They were therefore obliged to use the existing route established by the Montrealers, north from Cumberland Lake to the English-Churchill River and up it west to Lake Athabasca.

In these attempts to find a shorter route to Athabasca, the Hudson’s Bay Company was continuously harassed by the depredations of its rival, while simultaneously experiencing a lack of cooperation between the posts of Fort Churchill and York Factory, as well as something less than unanimity with regard to the recommendations made as to which route provided the best hope of success.

In the wintertime horses could not be used in the northern district and toboggans were unsuitable. Communications were maintained between important posts on principal routes by using sleighs hauled by dogs.

Carlton House was the meeting place of the winter express of the northern and southern districts. The north express via Green Lake, Lac Ile-a-la Crosse to Athabasca region. The south via Cumberland House and Norway House to York Factory. In 1832 the southern express travelled via Fort Pelly and Norway House.

The winter lake route ran from Swan Lake across to Lake Winnipegosis, through the Narrows into Lake Manitoba and thence overland to Fort Garry.

The wheels of the Red River carts gradually marked the prairie terrain with well defined tracks, one for each wheel, which in time wore down to deep ruts and became known as trails. These trails became numerous due to the increase in traffic and also the ease with which a new route could be taken over the flat prairie. The latter was subject in most cases, only to the natural impediments of lake, river, slough, marsh or ‘bluff’—the name given to a clump of shrubs or trees characteristic of the prairie landscape.

In later years identification of these trails became difficult. Many were wholly or partially obliterated by time, climatic conditions or settlement of the country. In some instances a change in the site, or the abandonment of a post, or the location of a new one, would change the route of the trail. A trail might be referred to under two or more names or would refer to two routes between two posts but known by one name. Generally the main trails followed the shortest practicable distance, between trading posts or depots, which were strategically established comparatively close to water transportation.

On the accompanying map ‘Principal Trails of the Red River Carts’ no attempt has been made to show all of the trails but rather the principal ones, in the era when the cart was one of the chief vehicles of land transportation. However, several important trail trunk routes merit special mention. These are the Carlton, Red River and Pelly as well as some of the major inland links which stretched across the west.

With the advent of the cart a new era in land freighting began. There were no roads but the prairie was not trackless. The millions of buffaloes which roamed the vast inland spaces had made tracks, extraordinarily enough, on some of the easiest grades and may have played a part in locating the first trails. The Indian too had left his mark on trail blazing, followed by the packhorse and the ‘travois’. With the cart the great inland country became accessible and the two-wheel trails were started.

The carts were first used for bringing meat of the slain buffalo back to the posts and in hauling ‘pemmican’ to the various depots. It was a highly nutritious food made with ground buffalo meat mixed with fat, and could be stored in bags for months without spoiling. It kept the men of the prairie fur trade going, and in many instances the availability of a supply, was as important as the location of a trail or post. It was to the inland transportation the counterpart of ‘hominy’ to the voyageur route on Lake Superior. The marks of the wheels made countless trails all over the great plains now known as Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and southern adjacent territory.

This [23] was the longest of the trails and ran approximately 900 miles from Fort Garry (Winnipeg) to Upper Fort des Prairies (Edmonton). At different times it was known as the Carlton, Saskatchewan, The Company and Edmonton Trail.

It started at Fort Garry and followed what is now Portage Avenue, Winni peg close to the north bank of the Assiniboine River to Portage la Prairie.

There it branched into two alternative routes for about 90 miles. The Southern branch continued westward about 20 miles and then veered in a northwesterly direction and crossed the Minnedosa River about 4 miles west of the present town of Minnedosa. It rejoined the northern branch about 20 miles west and 5 miles north of Minnedosa.

The northern branch of the trail ran northwesterly from Portage la Prairie close to the present village of Westbourne, Woodside and Gladstone, to pass about three miles north of Neepawa. It crossed the Minnedosa River about 2 miles northeast of Minnedosa and proceeded westward to Fort Ellice at the confluence of the Assiniboine and Qu’Appelle Rivers. Near Fort Ellice a short branch led into the fort, a Hudson’s Bay Company post, but this reunited with the main trail about 4 miles west of the post. From Fort Ellice to Touchwood Hills post the route followed substantially the same location as that chosen in later years for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad, with the town of Melville, Saskatchewan, about 2½ miles to the north.

Proceeding in a northwesterly direction over the saline Quill Lakes plains it passed a few miles west of the present town of Humboldt. In later years it branched again between Humboldt and the town of Duck Lake, with the southern branch located near the town of Bruno and crossed the South Saskatchewan River at Gabriel’s Crossing. From there it led an easy stage to Fort Carlton, on the east or right bank of the North Saskatchewan River. For several decades Carlton House was one of the principal depots of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the first was built in 1810 and the last one destroyed by fire during the rebellion of 1885.

Between Fort Carlton and Edmonton, the trail continued westward, north of Redberry Lake and south of Jackfish Lake near Meota, to the North Saskatchewan River and followed its north or left bank to Fort Pitt, Fort Vermilion (Lower Fort des Prairies) and Fort Victoria until it reached Edmonton (Upper Fort des Prairies).

An understanding of the genesis of the Carlton Trail is greatly facilitated if it is considered in three sections: the eastern, central and western.

The eastern section comprises the trail from Fort Garry to Fort Pelly, generally along the left bank of the Assiniboine River. This was well established in 1824 and no doubt had evolved gradually, as a result of the activities of buffalo hunting and the fur trade. After Fort Pelly was established as headquarters of the Swan River district in 1824, it was an alternative route to Fort Garry, instead of the old winter route [24] of Swan River, Lake Winnipegosis, Lake Manitoba and thence southeast to the Red River.

The western section from Carlton House to Edmonton, proceeded for the most part along the left bank of the North Saskatchewan River and doubtless was laid down by the early fur traders. Thus the location of the eastern and western sections was for all practicable purposes, fixed by the two rivers whose courses they more or less followed.

The central section, from the Assiniboine River west to Fort Carlton, underwent three locations by the time the final route was adopted. This was the outcome of a number of factors among which were: the amalgamation of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company in 1821; the establishment of Fort Pelly as headquarters of the Swan River district in 1824; the increase in the fur trade and location of new posts; the severe competition of the ‘free traders’, the growing importance of Fort Garry as a distributing and administrative center and the intrepid action of a governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company in virtually blazing a trail, across practically unknown prairie, as well as the demand for a shorter route.

In 1795 fur traders operated from posts on the Upper Assiniboine River, [25] at least as far west as Touchwood Hills and Quill Lakes and possibly beyond them. Accordingly when the central section of the trail from Fort Pelly reached as far west as the north shores of Quill Lakes, it traversed country, which was not entirely unknown. Thus in 1824 the trail from Fort Garry was along the Assiniboine to Fort Pelly and thence west to the vicinity of Quill Lakes.

The country between Quill Lakes and Carlton House was virtually unknown to the white man and inhabited by the Crees and the Saulteaux and their hereditary enemies, the Blackfoot Indians, and through which there was no definite route nor water course for guidance. Notwithstanding, Governor Simpson of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1825, when returning from a trip west, from Carlton House to Fort Garry, made a cross-country trip through this territory, which determined the course of the trail for the next twenty-seven years.

Simpson travelled south cast from Carlton House, crossed the South Saskatchewan River, passed south of Birch Hills and north of present day Humboldt. After four days and a somewhat harrowing experience of having lost their bearings and were on the verge of turning back, his party reached the north shore of Quill Lakes, where the area was recognized. He continued eastward south of Fishing Lake and crossed the Whitesand River to reach the Upper Assiniboine River area, about 16 miles southwest of Fort Pelly. From there they travelled southward along the right bank of the Assiniboine River to the confluence of the Qu’Appelle River, and thence along the eastern section of the trail to Fort Garry. This established the route of the trail until about 1852.

In 1850 the Qu’Appelle Lakes Post was erected and in 1852 Touchwood Hills Post started operation. This changed the course of the trail from north of Quill Lakes, to south of Touchwood Hills, although the former was still used by virtue of being a shorter route. In 1856 the Company adopted the new trail but the alternative lakes route was still available. Now the trail from Fort Garry passed through Fort Ellice, Fort Pelly, thence southwesterly to Touchwood Hills Post, then northwesterly, west of Touchwood Hills, Quill Lakes and Humboldt to Carlton House.

After the establishment of Touchwood Hills Post the ‘free traders’ cut across from Fort Ellice to the post thereby shortening the route by about 60 miles. [26] With competition becoming keener the need for the shorter route was recognized and the Company adopted it about 1860. The trail from Fort Garry now led through Fort Ellice to Touchwood Hills Post and thence northwesterly to Carlton House.

There were thus three locations of the Carlton Trail in the central section between the Assiniboine River and Carlton House; one Fort Pelly to Carlton House north of Quill Lakes established about 1825, another Fort Pelly southwest to Touchwood Hills Post about 1852; and finally Fort Ellice to Touchwood Hills Post about 1860.

The northern route of the trail, between Fort Pelly and Carlton House, experienced a brief resurgence about 1874-77. This was occasioned by the projected location of the transcontinental railroad and the telegraph line [27] passing through Fort Livingstone situated on the Swan River about 10 miles north of Fort Pelly. The proposed railway route followed fairly closely the old trail north of Quill Lakes to Fort Carlton. In 1872 Fort Pelly was discontinued as headquarters for the Swan River district, and in 1874 Fort Livingstone became the headquarters of the North West Mounted Police and the site of the temporary government of the North West Territories in 1876. In 1874-75 the first royal mail from Fort Garry to Edmonton passed through Fort Livingstone. The projected route of the railway was changed to farther south and the government and police headquarters were moved to the new site at Battleford in 1877 and thus any hope of reviving the old trail was doomed.

The Red River trail south from Fort Garry followed the west bank of the Red River and passed through or close to the present day towns of Ste. Agathe, and Morris to Pembina. From Pembina south there were three routes known as the ‘plains’ trails and the ‘woods’ trail.

There were two plains trails, one on the west side of the Red River and the other on the east side; the former going to Fort Snelling, the latter to St. Cloud. The woods trail joined the east plains trail just south of Wild Rice River, and proceeded generally in a southeasterly direction, through St. Cloud to St. Paul.

The west plains trail, which was located on the same side of the Red River as the trail between Pembina and Fort Garry, left Pembina in a southwesterly direction. It continued southward, west of the present cities of Grand Forks and Fargo and approached closely to the river in the vicinity of Fort Abercrombie approximately 35 miles south of Fargo. Proceeding along the Bois de Sioux River, which it crossed north of Lake Traverse, it continued south and about Big Stone Lake veered south east, not far from the north bank of the Minnesota River which it crossed at Traverse des Sioux, and followed the south bank into Fort Snelling.

The east Red River trail left Pembina for a short distance in an easterly direction then turned southerly and crossed the Red Lake and Wild Rice Rivers. South of the latter it veered southwesterly, crossed the Otter Tail River, passed Elbow Lake and curved in a southeasterly direction into St. Cloud. Major Stephen H. Long’s expedition of 1823 followed the trail from the Bois des Sioux River to Pembina.

Immediately north of Elbow Lake, on the east Red River trail, a relatively short trail branched off in a northwesterly direction, crossed the Otter Tail River and joined the west Red River trail just south of Fort Abercrombie.

The woods trail, through the forest area, in the south, was the most easterly of the three trails. It joined the ‘east’ Red River trail a short distance south of Wild Rice River and followed a southerly course past Detroit Lakes to Otter Tail Lake and Otter Tail River where it turned eastward to Crow Wing River after crossing which, it followed the north bank into Crow Wing, located at the confluence of the Crow Wing and Mississippi Rivers. From Crow Wing it continued along the east bank of the Mississippi through St. Cloud into St. Paul.

Fort Garry enjoyed a strategic position in the days of water transportation. It was accessible to tide water on Hudson Bay, as well as having access to the great Saskatchewan River system. In addition it was situated at the confluence of the Assiniboine and Red Rivers. which latter in its upper reaches was in relatively close proximity to the headwaters of the great Mississippi River. It was also geographically fortuitously located in respect to land transportation. As the latter superseded water transport and the Company adopted the land route from Fort Garry to St. Paul, in preference to boat travel to York Factory. Fort Garry became the focal distributing center, through which trade flowed to St. Paul and the eastern seaboard.

The origin of the Red River trails appear to be obscure. It is improbable there was much communication between the Red River Settlement and Minnesota River region prior to the establishment of Selkirk’s Colony at Fort Garry in 1812. After Fort Snelling was located in 1819 at the junction of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers, traffic became common, while by 1849 when Minnesota territory was organized, all trails were in more or less constant use and freighting with Red River carts became heavy between Fort Garry and St. Paul.

This trail between Fort Garry and St. Paul on the east side of the Red River, was referred to under two names. In the north it was called Crow Wing and in the south, The Old Red River Trail. [29] This along with independent records of the trails in the area, provide good evidence that the above names practically designated the old ‘East’ Red River trail and the ‘woods’ trail referred to in the preceding section (2) of the Red River Trails.

The trail named Crow Wing apparently followed generally the route of the ‘east’ Red River trail, east of the Red and south of Pembina as nearly as can be determined by the river crossings. Farther south, from where the ‘east’ and the ‘woods’ trails joined, just south of Wild Rice River, there is striking evidence, in addition to the principal points named, that it followed the route of the ‘woods’ trail, the most easterly of the Red River trails. The record gives the start of both trails in 1844, and the reason for building them was the same; to provide a route which would be safer than the west trail from attack by the warlike Sioux Indians. Also the descriptions given refer to both of them passing through heavy forest.

Now of the 49° parallel the Crow Wing trail on the east side of the Red River, passed about one mile east of Ridgeville, just north of the International Boundary in present day Manitoba, and continued through the towns of St. Pierre and St. Adolphe into Fort Garry. [30]

The trail was evidently named Crow Wing after the Crow Wing River along whose bank it ran, and the town of Crow Wing, at the confluence of the Mississippi, through which it passed.

Fort Pelly, built in 1824, was located at Indian Elbow, on the left bank of the Assiniboine River. All trails in this area leading into this post were generally referred to as Pelly trails, including the trail leading to Swan Lake, which however became known as the Swan Lake trail. At one time it was an important depot on the main trail of the Hudson’s Bay Company from Fort Garry to the Athabasca territory. [32]

Fort Pelly, situated on the Upper Assiniboine River, was in a strategic location and therefore a pivotal point, through which the trade passed to the embarkation point on Swan Lake for York Factory. In reverse manner the incoming freight followed the route for the distribution of goods to the various inland posts and depots. It was the headquarters of the Swan River district from 1824-72.

There were two trails between Fort Pelly and the junction of the Qu’Appelle River with the Assiniboine, later the site of Fort Ellice; one on each side of the Assiniboine River.

The Pelly trail on the right bank of the river was considered the main trail of the Hudson’s Bay Company, while Fort Pelly was the headquarters of the Swan River district until 1872. This followed generally the route taken by Simpson in 1825, as described herein under the Carlton Trail, except it was linked with Fort Pelly.

The Pelly trail on the left bank of the Assiniboine followed the river to the junction of the Qu’Appelle River. It began as an old trail of the fur traders and was used by the Hudson’s Bay Company for the greater part of the 19th century. It came into prominence after Fort Livingstone became the headquarters of the North West Mounted Police in 1874, and passed near the present towns of Russell and Binscarth to Fort Ellice, where it met the old stretch of the Carlton trail to Fort Garry. Later the southern section of the trail, east of the Assiniboine took a shorter route to join the Carlton Trail, which bypassed Fort Ellice. This branch left the trail about the present town of Cracknell in a southeasterly direction, passing to the east of Russell and west of Angusville to Shoal Lake. Shoal Lake was approximately 30 miles east of Fort Ellice and was an important post of the North West Mounted Police for several years. This trail carried heavy traffic during the period when Fort Livingstone was in operation.

Fort Livingstone was located, on the south side of Swan River, where a tributary Snake Creek joined it, about 10 miles north of Fort Pelly. It was also known as Swan River Barracks, and was on the old trail to Swan Lake. It came into temporary prominence between the years 1874-77, with the projected location of the transcontinental railroad; the telegraph line between Selkirk and Edmonton; the headquarters of the North West Mounted Police and the temporary seat of government of the North West Territories. Its close location to Fort Pelly, and being on the route to Swan Lake, gave it all the advantages enjoyed by Fort Pelly.

This trail is the oldest of the trails in the area. It was started after the establishment of Marlborough House at Indian Elbow on the Assiniboine River in 1793, by the fur trading companies. It was a chief factor in the location of Fort Pelly, because a good cart road existed between the Elbow and Swan Lake.

The Swan Lake trail [33] from Fort Pelly, followed the east bank of Snake Creek, through Fort Livingstone to the most westerly crossing place of Swan River, along whose north bank it ran to Swan Lake. From Swan Lake the old Swan River Brigade started the long journey down Shoal River, between Swan Lake and Dawson Bay on Lake Winnipegosis. It continued by either the eastern or western portage across Cedar Lake, then down the Saskatchewan to Grand Rapids on Lake Winnipeg. From there the route skirted the northern shore of the lake to Norway House and on to York Factory.

The trail on the south side of Swan River was used to a much lesser extent than the main one on the north side, in the days of the fur trade. It became well known however when the proposed transcontinental railway was surveyed from Selkirk across the Narrows of Lake Manitoba to Fort Livingstone.

This trail [34] is difficult to document in certain sections because identification of it appears to have been obliterated and since there were evidently two Yellow Quill trails branching off the Carlton trail. One was at Portage Ia Prairie and the other just east of the town of MacGregor.

The trail starting east of MacGregor is shown on a map in the “Historical Atlas of Manitoba 1970" reproduced from the manuscript map [35] in the Public Archives of Canada, and is marked the Yellow Quill Trail. It leaves the south branch of the Carlton trail about 3 miles east and one mile south of MacGregor and proceeded in a southwest direction to pass just east and south of the town of Pratt, about 12 miles southwest of MacGregor.

The trail starting at Main Street and Saskatchewan Avenue in Portage la Prairie ran southwest about 12 miles along the left bank of the Assiniboine, through the Long Plains Indian Reserve Number 6. South of this Reserve it turned west, passed about a half mile south of Lavenham, and on to about one mile south of Pratt, where it joined the branch from MacGregor.

A plan [36] number 395 dated 1886 shows the trail which started from Main Street and Saskatchewan Avenue, at Portage la Prairie. It is called an ‘Old Trail from Portage la Prairie along the Western Side of the Assiniboine River’. It shows the trail ran southwest about 12 miles from Portage la Prairie. The trail is not named Yellow Quill but just an old trail. Considerable research has been done on this trail which indicates it was the Yellow Quill.

West of Pratt, where the two branches joined, the trail continued west as the Yellow Quill. It crossed from the left bank to the right bank of the Assiniboine at the first sites of the North West and Hudson’s Bay Companies’ posts about 3 miles north of the town of Treesbank, and a few miles west of the confluence of the Souris River with the Assiniboine. It then proceeded to about 2 miles north of Rounthwaite toward Hazelwold, at which point identification ceases. This is in a hilly sandy terrain and doubtless the trail has long since been obliterated. The trail passed about a half a mile north of Souris and it is reasonable to assume it followed a west and southerly course to that point.

From Souris it followed the left bank of the Souris River, past Hartney, through Melita and on to the confluence of the Souris with Gainsborough Creek. It follows the north bank of the Gainsborough and crosses it about 10 miles east of the Saskatchewan border, where it united with the Boundary Commission Trail and crossed the Saskatchewan border about 5 miles north of the United States boundary. It presumably continued west toward the headwaters of the Missouri River.

The Yellow Quill Trail was named after Chief Yellow Quill of the Long Plains Indian Reserve Number 6 and the Swan Lake Indian Reserve Number 7 of the Saulteaux Indians. Number 6 was located about 12 miles southwest of Portage la Prairie on the left bank of the Assiniboine. Number 7 Reserve was just north of Swan Lake, in the vicinity of the headwaters of the Pembina River, and a few miles cast of Mariapolis on highway 23.

Between the two reserves there was a place called Indian Ford, near the present town of Rathwell. Legend states the Saulteaux Indians went there to get eagle feathers for their tribal dress, because it was the only place in the area where the eagles nested.

This trail [37] was developed from an old Indian trail dating back to earliest times. It is one of the most legendary routes of all the trails which bound together the distant posts from the Red River to the Rockies.

The trail headed west from Fort Ellice, through present day Rocanville and passed just south of Broadview, through Wolseley, where it veered northwest and passed about one mile east of Indian Head into Fort Qu’Appelle. Fort Qu’Appelle was like the hub of a wheel with trails leading out in all directions like spokes. The trail from Fort Qu’Appelle to Touchwood Hills Post connected the Fort Qu’Appelle Post with the main Carlton trail. Palliser and Hind exploration expeditions travelled this trail in 1857 as well as the Earl of Southesk in 1859.

This trail [38] from Montana crossed the International Boundary south of the present town of Bracken, Saskatchewan. It led to just east of Swift Current and veered northeast to the Elbow on the South Saskatchewan River. It continued north as the Elbow-Fort a-la-Corne trail, east of Saskatoon and joined the south branch of the Carlton trail near St. Julian, where it crossed the South Saskatchewan River in the vicinity of Batoche and continued to Carlton House. From Carlton it was designated the Carlton Fort a-la-Come trail and passed through Prince Albert to Fort a-la-Come, (Fort des Prairies) about 13 miles downstream from the confluence of the north and south Saskatchewan Rivers.

The route of this trail [39] was north from Swift Current crossing the South Saskatchewan River at Saskatchewan Landing. It went through the present town of Fiske and continued north, about 10 miles west of Biggar into Battleford.

It was one of the main trails of the era and served as a route between the important centers north and south. In 1885 troops under the command of Colonel Otter, made a forced march along this trail about 225 miles in ten days. The deep ruts made by the Red River carts and other vehicles could still be seen in 1965, along many stretches of the trail.

Fort Macleod was situated on Old Man River about 90 miles south of the present city of Calgary, in southwestern Alberta. The trail [40] led eastward through Whoop-Up to Fort Walsh in the Cypress Hills, which was established in 1874 and became headquarters of the North West Mounted Police in 1878. The trail continued eastward to Fort Qu’Appelle, passing just east of Moose Jaw and north of Regina. It was a regular trade route and an overland thoroughfare connecting the outposts of the fur trade activities.

Wood Mountain was located southwest of Moose Jaw about 25 miles north of the 49° parallel of latitude. It was an important post from which a number of trails branched out, including one to Montana. As a North West Mounted Police post it gained prominence from 1876-81, when a handful of men of the famous force controlled the powerful Sioux Nation.

The route of the trail [41] led eastward through Weyburn and just north of the town of Carlyle and veered northeasterly into Fort Ellice. A trail from Wood Mountain westward to Fort Walsh established communications between those two posts.

This trail ran from Battleford on the North Saskatchewan River to the confluence of the Red Deer River [42] at the western border of the Province of Saskatchewan. The route followed a northeast direction from the forks of the rivers, passing west of the town of Kerrobert to Battleford. It would appear this route merged at Kerrobert with the Medicine Hat to Battleford trail.

It was part of an historic trail whose ruts deeply grooved the prairie sod, and there is a possibility these old marks had their origin in the great “Old North Trail" from the Blackfoot country to Mexico years ago. It was used by Indian foot-travellers centuries ago and continued into the time of the mounted tribes.

Traders from the vicinity of Battleford are said to be the first white men to use this trail, and were followed by others after the beginning of the 19th century, from the area near the forks of the Red Deer and South Saskatchewan. A trail ran from the forks to Swift Current to connect with ,he trunk route from Montana to Elbow and on to Fort a-la-Corne.

From Carlton House this trail [43] ran northwest to Green Lake, a distance of approximately 150 miles. It passed on the west side of Sandy Lake to a present town named Pascal, whence it turned west to Ranger and turned northeast of Chitek Lake to Green Lake. Following the western shore of the lake it ran to Green Lake Post. The trail was built in 1875. A small stream about 3 miles long connects the north end of the lake with the elbow of the Beaver River, where it turns and flows north to Lac Ile-a-la-Crosse.

The first post was built at Green Lake in 1782 by the Montrealers and the Hudson’s Bay Company built their first post, Essex House, in 1799 which later became known as Green Lake Post. It was the fastest overland route between the Saskatchewan and English-Churchill River drainage areas.

Goods and furs moved via this trail for Ile a-la-Crosse and up to La Loche (Methye) Portage and the Athabasca territory, and the winter express travelled it from Lake Athabasca to York Factory or to the Red River.

Near the present village of Nebo a branch from this trail ran east to Prince Albert, a distance of about 50 miles.

This short trail [44] ran from Prince Albert north to Montreal Lake, a distance of approximately 60 miles. It travelled along the eastern boundary of present Prince Albert National Park and its terminus was near the southeastern shore of Lake Waskesiu. From there a constructed road led to the post at the south end of Montreal Lake.

At Fort Macleod this trail [45] crossed Old Man River and ran west of north to Fort Calgary, a few miles south of the present city of Calgary. It crossed the Red Deer River south of today’s town of Red Deer, and continued to the crossing of Battle River, passed at or near the town of Leduc into Edmonton.

A trail ran west and north from Calgary and apparently joined the trail from Fort Macleod, at a place named the Lone Pine south of the Red Deer River. The Fort Macleod-Fort Calgary-Edmonton Trail connected North West Mounted Police posts in 1886.

From Edmonton this trail [46] led southeast across the Battle River to the Bulls Forehead at the forks of the Red Deer and Saskatchewan Rivers. It then continued south into Fort Walsh. This trail was also used between North West Mounted Police posts in 1886.

Starting from Fort Macleod this trail [47] ran in a northeasterly direction to cross the Bow River at Blackfoot Crossing in the Indian Reserve. It then veered north along the Red Deer River which it crossed and continued north, crossing the Battle River to reach Edmonton.

This location from a map of ‘Special Survey of Standard Meridians and Parallels’ for Dominion Lands during the year 1878, in relation to latitude and longitude. [48]

The Dawson Trail [49] was built to provide a road from Winnipeg east to the North West Angle Inlet of the Lake of the Woods, a distance of approximately 115 miles. The Dawson route from Winnipeg to Fort William, a distance of about 530 miles included both road and water routes.

The Provincial library file on this trail records it started at Point du Chene (Oak Point) which today is known as Ste. Anne, about 30 miles east of Winnipeg. Ste. Anne was on the Oak Point trail which ran south of the Seine River and west of Ste. Anne curved south before turning northwest into Winnipeg. There is however evidence to indicate the Dawson Trail, on the north side of the Seine from Winnipeg went through the towns of Prairie Grove and Lorette to Ste. Anne. [50]

From Ste. Anne it ran east through Richer, whose main street is on the route and proceeded across the Brokenhead River near its source, to the Whitemouth River. The bridge across the Whitemouth no longer exists, but the trail ran eastward to cross the Birch River north of Birch Lake. Thence it turned southeast to Harrison Creek, whose north bank it followed to the North West Angle Inlet on Lake of the Woods, in United States territory. The clearing made for the trail in the woods is still visible and it intersects the present provincial highway 308 about 5 miles or so south of East Braintree.

The trail was named after Simon James Dawson, a civil engineer who surveyed the route, and its purpose was to provide a connection, on the western end of the route, between Fort William and the prairies.

The construction of the trail provided a relief project for the Red River settlers whose crops were destroyed by grasshoppers in 1869. Men were brought in for the work, which aroused the ire of the Metis and was a contributory factor in the grievances leading to the rebellion of 1885. The first to travel the trail were the troops of Colonel Wolseley’s Red River Expeditionary Force. Stage coaches used it for carrying the Royal Mail. Ox carts made their squeaky way along it taking supplies to the construction gangs.

The Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada in 1940, unveiled a cairn to commemorate this road at Ste. Anne, whose inscription reads:

“This land and water route from Fort William to Red River was Canada’s attempt to provide an all Canadian highway linking the east with the prairies. Length 530 miles; surveyed 1858; begun in 1868; completed in 1871."

A brief description of the buffalo hunt is relevant here because of the great contribution the buffalo made in providing sustenance for the fur trade and the important part played by the Red River carts in the renowned hunts, which in their day attracted personages from far and wide.

The buffaloes were once the monarchs of the plains, which were their richest pasturing grounds. This animal was immensely strong and considering its great size had agility and speed. It furnished almost all the food for the entire fur trade in the west and its carcass supplied many of the necessities for survival in an inhospitable climate. In 1870 it was officially adopted as the animal emblem of Manitoba. Two massive bronze statues of buffalo adorn the entrance to the Grand Staircase, which leads to the Provincial Chamber in the Legislative Buildings in Winnipeg.

Buffalo hunting was the favorite sport of the Métis while at the same time providing food. With the coming of spring each year the hunters started preparing for the hunt. There were two semi-annual buffalo hunts; one in the fall and the more important one in the spring. In preparing for the hunt the plains mania took hold of the colony and everything was brought to a standstill, while an air of anticipated festivity prevailed. After the expedition started there was hardly anyone left in the Red River Settlement.

Pembina was the rendezvous point. In the spring hunt of 1850 the venerated Father Lacombe [51] was the chaplain. In the great spring hunt of 1840 the following detailed description has been passed on to us by Alexander Ross. [52]

On June 15, 1840, the carts emerged from all parts of the Settlement and after the hunters obtained their requirements on credit, the cavalcade left Fort Garry and after three days travel it reached Pembina where it camped for three days.

The camp was circular in form and occupied as much area as would a city of that time. The carts were placed in a circle, side by side, with trams outward. With the circle of carts, tents were placed in rows at one side, and animals on the other in front of the tents. This was the arrangement in hostile country but where there was no danger, the animals were kept on the outside. The circle of carts served the double purpose of, securing the people and animals within, as well as a place of shelter and defence against an attack from without.

After establishing camp and assembling, the roll was taken, the rules and regulations for the expedition were finally settled and the officials for the trip were chosen and installed in office. First a council for the nomination of officers was held which included: ten captains, each with ten soldiers under his command; ten guides and a chaplain.

There was a camp flag which regulated the making and breaking of camp, as well as the division of authority, when on the trail or in camp. It was placed in the possession of the guide for the day, who was the standard-bearer. The raising of the flag in the morning, was the signal for breaking camp, and when lowered in the evening, it was the sign for making camp. During the march the flag was flying and while it was up, the guide was the chief of the expedition and everyone was subject to his orders. When the flag was lowered for camping, the captains and soldiers’ duties commenced.

The senior captain, an experienced and responsible individual, was named head of the camp and on all public occasions occupied the place of authority. The captains were in command when in camp. The guide of the day was chosen in turn, from the ten guides nominated and he decided the route of travel. The captains directed the order of the camp and each cart as it arrived was assigned to its proper place. Everything was done with regularity.

When all was ready to leave Pembina, the captains and other chief men held council, and laid down the rules for the hunt. On this occasion they were

Early on June 21, 1840, they left Pembina after the priest had performed mass and the camp flag raised. The picturesque procession stretched some five or six miles, along the trail to the southwest. With a brief rest at noon, they travelled until five or six o’clock for night encampment. On this day they travelled twenty miles. After camping, a council meeting was held on the grass outside the circle of carts.

The next day the march was cancelled because some of the horses and oxen strayed away and had to be rounded up. On June 23rd the march resumed and they were now seeking the buffalo herds. After nine days out of Pembina, they reached the Chienne (Cheyenne) River, about one hundred and fifty miles from Pembina, and had not seen a herd of buffalo. On July 3, nineteen days out of, and more than two hundred and fifty miles from the Settlement, they came in sight of the hunting ground and the following day had the first buffalo ‘race’.

Four hundred mounted huntsmen awaited the signal from the senior captain and at eight o’clock in the morning moved toward the herd, which was about one and one-half miles away. The runners approached to within four or five hundred yards before the herd took flight, as the hunters moved in. Then shooting, yelling, noise, dust and general pandemonium broke loose and the earth trembled, as the thundering herd stampeded. In a short time the tumult died away in the distance, leaving the slain buffalo on the plain. A perilous but glorious adventure, yet sometimes fatal to both man and horse.

The carts then moved forward to garner the meat. The hunters skinned and cut up the carcasses. The women began work on the skins, as well as the meat in the preparation of pemmican. The meat had to be processed immediately to prevent spoiling. In this ‘race’, thirteen hundred and seventy-five buffalo were killed.

The expedition followed the buffalo herds west and reached the banks of the Missouri River on July 16. They spent a week there in forays after buffalo. On July 25, on their return trip home they were in the vicinity of the Chienne River. They passed through Pembina and on to the Settlement at Fort Garry, where they arrived on August 17, after a hunt lasting two months and two days.

There were sixteen hundred and thirty persons and twelve hundred and ten Red River carts in this expedition. It was estimated that a total of 1,089,000 pounds of meat were obtained on this hunt. During the spring or summer hunts, an expedition averaged about ten to twelve general races’, that is when all the hunters ‘run’ at once. On these hunts there was great wastage of the spoils and scarcely one-third of the buffalo slain were turned into account.

Before the white man came to the plains with fire-arms it was estimated there were between fifty and sixty million buffalo roaming the prairies. By 1870 only about four and one-half million remained. Man’s slaughter and natural catastrophe had taken a prodigious toll. Today they have disappeared, except a few confined to parks for display or to prevent their complete extinction.

By 1860 increasing traffic and changing routes were shifting the focal point of transportation to Fort Garry. The direct route of the Carlton trail had reduced the distance between Fort Carlton and Fort Garry by some 60 miles. The Hudson’s Bay Company was abandoning the difficult route down the Hayes to York Factory, in favor of shipping southward over the Red River trails to the Mississippi system. Fort Garry was attaining greater status as a distributing and administrative center.

Vehicles with the power of an animal were becoming inadequate for the volume of traffic and the increasing demands of the market for faster movement of merchandise, which was by steam motive power. Similar to the earlier day, when the pack-horse was superseded by the cart, in like manner the cart was to give way to the steamboat and the railroad.

In 1859 the sternwheel steamboat Anson Northup made the initial trip from Georgetown, near Moorhead, Minnesota, down the Red River to Winnipeg. [53] In 1867 the railroad reached St. Cloud, Minnesota, and was pushing northwest to St. Vincent at the border near Pembina. In 1881 the railroad had reached beyond Portage la Prairie and was heading westward.

These events signalled the beginning of the end of the Red River Cart, which had performed meritorious service, until it had practically disappeared from the trails by the end of the century. The early cart which later became known as the Red River Cart had become the historical symbol of the Province of Manitoba.

In 1971 little remains of the factors which made such a great contribution to the early development of the west. The old posts of the fur trade have disappeared. The cart trails have been obliterated. The buffalo hunt is but a memory. The Voyageurs and their canoes as well as the Orkneymen and their York boats, have vanished. The fur traders are silent. The Red River Carts are gone, except for a few dilapidated exhibits in museums.