by George F. Reynolds

Winnipeg, Manitoba

MHS Transactions, Series 3, Number 26, 1969-1970 season

|

When the paddle-wheeler Anson Northup slowly wound her way down the Red River to Fort Garry in the early summer of 1859, she had on board a young man who was destined to play a most significant role in the development of the future city of Winnipeg. The passenger’s name was Henry McKenney. Three years later he built the first store at what came to be known as ‘the corner of Portage and Main.’

Henry McKenney was born at Amherstburg, Upper Canada, circa 1826, the second son of Henry McKenney (the elder) and his wife, the former Elizabeth Reily, who had arrived in Amherstburg in 1823 from Ireland, with her widowed father, John, and her three sisters. Young Henry McKenney married Lucy Stockwell in 1845. Their children, born at or near Amherstburg between the years 1847 and 1851, were in order of birth, Lucy, John and George. There may also have been a son older than Lucy and there is believed to have been another daughter, younger than Lucy. [1] Accompanying McKenney on the maiden voyage of the Anson Northup were his wife, their son John [2] and possibly one or more of their other children.

Henry and his older brother Augustus operated a frontier trading store during the 1850s in Minnesota Territory which until 1857 extended as far west as the Missouri River. Where the McKenneys had their post is not definitely known but there is some evidence that it may have been on the line-of-route between St. Paul and Pembina, possibly on the upper reaches of the Red River.

After safely landing his family at Red River Settlement in June 1859, Henry McKenney wasted little time in getting down to business. He acquired a large wooden building from the pioneer trader Andrew McDermot and converted it into a hotel in order to accommodate the influx of visitors and commercial men who were expected in the Settlement following the commencement of direct steamboat service. This stopping place, which he named “The Royal Hotel,” was the first hotel in Manitoba to open its doors.

McKenney’s hotel was built (like many of McDermot’s other buildings) [3] on high ground, well above the spring flood plain, some 500 feet back from the Red River. The actual site of “The Royal” was probably between McDermot and Bannatyne Avenues with the weight of evidence favoring a location near Bannatyne.

While McKenney ran a cozy and home-like inn, he did not provide hack service for his guests, an early traveller having recorded that he had to hire an ox-cart to take his moveables from the dock to the hotel.

Although Henry (or Harry), as he was frequently called in the Settlement, did not obtain a liquor license until 1861, his hotel soon became a popular rendezvous. In addition to the hotel business, he opened a general store on the premises and started trading in pemmican and fur. That his establishment rapidly became well-known is indicated in rather a curious way by an advertisement in the pioneer newspaper, the Nor'Wester, 28 January 1860 in which A. G. B. Bannatyne advised prospective customers that his store (which had been in business for some eight years) was located “near the Royal Hotel” (which had only been open a few months).

In the early part of March 1860, a large group of Bois Brules held a meeting in the Royal Hotel to protest against discrimination and the lack of certainty respecting their land tenure. The Nor'Wester has been blamed for stirring up the mixed-blood descendants of the aborigines by the printing of inflammatory letters and editorials.

On 15 March 1860, Henry McKenney appears for the first time before the General Quarterly Court of Assiniboia [4] to sue Clinton Geddings and George Moar for recovery of a debt. McKenney might well be classed as a compulsive litigant. During the succeeding nine years he was before the Quarterly Court as plaintiff or defendant in no less than thirty actions and there is no record of how many times he patronized the lower courts. In the absence of “professional” lawyers at Red River, it was customary for those appearing in court either to act on their own behalf or have a friend do so. McKenney relished the role of backwoods legal expert. If he wasn’t pleading one of his own cases, he was quite willing to step forward and act as advocate for anyone requesting his services.

Sometime during the winter of 1859-1860, McKenney invited a young relative of his to spend the following summer in the Settlement. Thus, when the Anson Northup pulled up to the dock at Fort Garry on 1 June 1860, one of her 25 passengers was a tall, handsome youth who is said to have had “the obvious characteristics of Viking ancestry.”

He was Henry McKenney’s half-brother, John Christian Schultz. Before the decade was over he was to become one of the most controversial figures in Manitoba history and in the process the bitter enemy of Henry McKenney. The relationship between McKenney and Schultz came about in this fashion. Henry McKenney’s widowed mother, Mrs. Elizabeth McKenney, married William Ludwig Schultz, a native of Bergen, Norway, whose father had been knighted for service in the Royal Danish navy during Napoleonic times. On 1 January 1840, a son (their only child) was born to the Schultzs at Amherstburg and christened John Christian.

According to family records [5] their marriage was not a happy one; the pair separated, and the mother, fearing the father might seek custody of the child, sent young John Christian to live with her sister May. Her husband, Captain Hackett, was keeper of the lighthouse on Bois Blanc Island, opposite Amherstburg, a few miles downstream from Detroit. The island proved a safe haven and when the father left the district “John Christian again went to live with his mother and the McKenney boys but spent much of his time at Mrs. Andrew Kemp’s (his Aunt Anne), with the Kemp children who were nearer his own age. His mother died while he was still quite a young man. He was ambitious and early learned to shift for himself but undoubtedly Henry McKenney helped him a lot.” This statement by one of the immediate family is interesting in view of what took place between the two men in later life.

One of the strangest ramifications of the McKenney-Schultz story is that following the death of his wife, William Schultz returned to Amherstburg and eventually married Mrs. Mathilda McKenney, the widow of Augustus McKenney, the eldest son of his late wife by her first marriage. [6]

When John Christian was eight years old, the Kemps moved to Kingston, Upper Canada. Ten years later he followed them and enrolled in what was then known as the University of Queen’s College, to study medicine. He remained at Queen’s for two full sessions (1858-59 and 1859-60), [7] boarding with his Aunt Anne during that period.

The Queen’s University calendar for 1858-1859 listed these prerequisites for entry into medicine: “Students, previously to their attending the Professors of Medicine, shall have attended the Latin, Greek, Mathematics and Philosophy classes of this, or in some other University, or shall possess such an amount of knowledge of these branches of study as shall enable them, upon examination, to rank with those students who have attended these classes.”

How Schultz fulfilled these pre-med requirements remains a mystery. It has been claimed that Schultz was a student at Oberlin College prior to entering Queen’s but Oberlin has no record of his enrolment at that institution. [8]

Schultz, a vigorous outdoors-type, was immensely attracted to the life in Red River Settlement and spent all the time McKenney could spare him exploring the country on horseback.

On 22 July 1860, a large cart train, supervised by Henry McKenney, left the Settlement and headed for St. Paul, Minnesota. McKenney’s wife and young protege remained behind to run the hotel and store. Under normal conditions a round trip by Red River cart between Fort Garry and St. Paul took about three months. Before McKenney had returned, Schultz left for the east, travelling via the Crow Wing Trail. His departure date was 18 October 1860, and it took him 15 days to cover the 300 odd miles to Crow Wing village, reaching St. Paul early in November. His time of arrival in Upper Canada would therefore be about the middle of November.

While Schultz was heading back to medical school, McKenney was on his way home to Red River with the cart train, arriving in the Settlement near the end of October. He was accompanied on the return journey by another well-known Red River merchant, W. G. Fonseca.

When the Anson Northup reached Fort Garry on 2 November 1860, to complete the last voyage of the season, she had on board several cases of goods consigned to ‘McKenney and Company.’ The Company was a partnership between McKenney as senior and Schultz as junior member. When and where the partnership was agreed upon is not known; possibly before McKenney left the Settlement in July; possibly they met and reached a final understanding somewhere on the trail between Crow Wing and Fort Garry. In any event, the original financial stake of the impecunious medical student in the enterprise must have been small indeed.

A long editorial in the 29 October 1860, Nor'Wester may have had considerable influence on the futue commercial career of Henry McKenney. The writer called for the establishment of a sawmill on Lake Winnipeg to use the tremendous supplies of timber available there for the benefit of the Settlement. At that time buildings at Red River were usually framed from hewn logs. Such lumber as was obtainable was either imported from Minnesota at high cost or was sawn locally by the laborious and back-breaking methods of pit-sawing with very limited quantities of finished lumber being planed by hand.

During the winter of 1860-1861 McKenney made his first trip into the North country, trading in fur and quite likely keeping his eyes open for good stands of timber for his future lumbering operations.

The 1 June 1861, Nor'Wester noted that “Mr.” Schultz had lately arrived from Canada. (He must have made the journey from Georgetown on horseback as the first boat of the season did not reach Fort Garry until 11 June.) Two issues later, on 15 June, the following announcement appeared:

“Dr. Schultz - Physician and Surgeon

Residence - Royal Hotel - Upper Fort Garry.”

In recent years a cloud of suspicion has fallen over the medical qualifications of Schultz as questions began to be asked as to when and where he had obtained his degree. Schultz, for reasons unknown, had not returned to his studies at Queen’s University the previous fall but had enrolled instead at the Toronto School of Medicine which had been affiliated with Victoria College at Cobourg singe 1854.

He apparently completed the academic year 1860-1861 at the Toronto School of Medicine but according to the University of Toronto (which assumed custody of the records of Victoria College when that College affiliated to the University in 1892), Schultz did not receive an M.D. degree from the Toronto School of Medicine (Victoria College). [9] In any event, by the end of the 1860-1861 session he could have completed no more than three years of the prescribed four year course in Medicine.

There appears to have been an aura of incertitude surrounding Schultz’s doctorship even during his early days at Red River. Hargraves [10] made the rather enigmatic assertion that Schultz “was understood in the Settlement to have obtained his degree from a Canadian Medical School.”

The fact remains that regardless of where, when and if Schultz was granted a diploma from a recognized school of medicine, he did practise as physician and surgeon for a large and presumably satisfied clientele during the next several years.

On 5 June 1861, the Governor and Council of Assiniboia [11] granted a liquor license to McKenney and the Royal Hotel thus became the first “licensed premise” in Manitoba.

At a meeting of the Council of Assiniboia held on 8 June 1861, Governor Mactavish presiding, steps were taken to fill some of the numerous vacancies created by the sudden death of Doctor John Bunn.

In addition to being a Councillor, he had been Chairman of the Board of Works, Magistrate, Sheriff, Governor of the Gaol and Coroner. There were two applicants for the shrievalty, James Ross and Henry McKenney. By a 10 to 1 vote of the Council, James Ross (who served as Postmaster and was also Editor and part-owner of the Nor'Wester) was named Sheriff and Governor of the Gaol at the salary of £30 Sterling per annum. At the same Council sitting, McKenney was appointed a Petty Magistrate (or Justice of the Peace) of the Middle District Court at a salary of £5 Sterling per annum. The Middle District of Assiniboia extended from Sturgeon Creek on the Assiniboine of Middlechurch (St. Pauls) on the Red River.

Appointment to the magistracy was considered a status symbol in the community; legal training was not a prerequisite. In fact, some Justices of the Peace were quite illiterate.

Any pleasure that McKenney might have felt over his election to the Bench was soon dispelled by an editorial in the 15 June 1861, issue of the Nor'Wester. Ross came out with a blast at McKenney’s assignment: “A magistrate is an officer of the peace, and the intimate connection between McKenney’s calling [purveyor of liquor] and breaches of the peace, is too manifest to require elucidation, and too obvious for the people to regard the appointment as a proper one. There are many who object on the ground that he is a stranger. This is a consideration, certainly, but in our view not quite so important as the former.”

There is an undertone of resentment here, the Red River Establishment criticizing an upstart Upper Canadian for trying to take an active part in the affairs of the Settlement. This was not the last time McKenney was to receive rough treatment at the hands of the Press.

One of the schemes entered into by McKenney and Company that summer was an excursion into the Saskatchewan River country to trade with the Indians. Later, McKenney took a trip to Canada; the Nor' Wester reported that he had returned on the Pioneer (the rebuilt Anson Northup) on 15 September.

On the day he arrived back at Red River, McKenney was involved in an incident concerning a mixed-blood by the name of Hupe. An editorial in the Nor'Wester headed “A magistrate trying to nullify a decision of the Court,” alleged that McKenney had evicted Constable McDougall from his store, using threats and strong language when McDougall tried to arrest Hupe on the premises. Hupe had been convicted on a debt charge and, having failed to pay up as directed by the Court, a warrant had been issued for his apprehension.

In the same article Ross castigated McKenney sharply for being absent from the Settlement for 8 or 9 months at a time. Whether or not he was resentful of the criticism, McKenney resigned as Petty Magistrate at the next (November) sitting of the Council of Assiniboia.

During the winter of 1861-1862 McKenney was again away from Red River on a fur-trading venture in the Lake Winnipeg and Saskatchewan River districts.

By the spring of 1862, the business of McKenney and Company had prospered to such an extent that McKenney decided to get out of the hotel trade and to build a larger general store at a new location. His choice of a site was to have a profound effect on the development of the future city of Winnipeg.

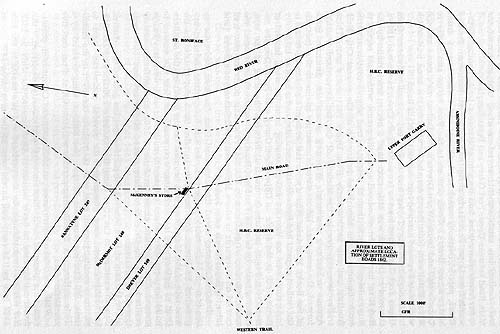

In order to understand why McKenney selected the location he did, some knowledge of the river lots and of the roads and trails in Red River Settlement is necessary.

All that section of central Winnipeg situated between Market Avenue (and its projection westward) on the north, and Notre Dame Avenue (and its extension, Pioneer Avenue, formerly called Notre Dame Avenue East) on the south, was originally divided into three river lots. The most southerly of these was listed as Lot 249 in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Land Register ‘B.’ [12] The next going north was number 248; this lot was 12 chains 80 links (844.8 feet) wide and belonged to Andrew McDermot. Finally, number 247, first owned by James Sinclair, but later transferred to A. G. B. Bannatyne, was a narrow lot only 5 chains 93 links (391.4 feet) wide.” These three lots stretched back westwards from the Red River for nearly two miles to the vicinity of Arlington Street and according to Land Register ‘B’ had parallel sides bearing N 65 W. In actual practice there was some variation in the azimuth of the side lines as laid out on the ground. South of Lot 249 were lots 1210 and 1211, collectively called the ‘Hudson’s Bay Company Reserve’ with a total area of about 465 acres. This large plot of land was used as a campground by Indians and tripmen from the woods and plains.

Bannatyne’s Lot 247 and McDermot’s Lot 248 were held in fee simple, either by purchase or grant from the Honourable Company. Lot 249, registered in the name of William S. Drever, was not owned outright by him. As recorded in Land Register ‘B,’ he was allowed to occupy it “during the pleasure of the HBC but if taken from him the value of the improvements thereon to be paid by the HBC and six months notice to be given before removal.” There is an important titular distinction here which was to influence future events.

Drever was one of the petty free traders who were formerly in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company and who, on termination of their contract, had settled at Red River. Drever’s Lot 249 was only 3 chains (198 feet) wide and had, in fact, been sliced off the northern boundary of the HBC reserve. The southern boundary of Lot 249 coincides with the north side of Notre Dame Avenue and had a true bearing of N 63 deg. 37 min. W. All avenues in the central core of Winnipeg north of Notre Dame Avenue were in later years laid out parallel to this original lot boundary. The northern boundary of Lot 249 (which is the southern boundary of McDermot’s Lot 248) runs along the south side of Portage Avenue East (originally called Thistle Street) and cuts through the northwest corner of Portage and Main.

The Council of Assiniboia at their meeting of 25 June 1841, had decreed that “effective August 8, 1841, the Main Highway shall be widened to two chains (132 feet) at public expense, the bush to be cut down and either fence if necessary moved back.” Compensation for any enclosed ground expropriated was promised by the Board of Works, “according to the evidence of disinterested neighbors.” By 1862 the route of the Main Road running northwards from Upper Fort Garry through the Kildonans and on down the river to Lower Fort Garry was fairly well established by communal usage although even the first part thereof, between the present Federal Building and the City Hall, was not actually surveyed and graded until 1871. Prior to 1862 there were no business establishments anywhere along that stretch of the Main Road between Upper Fort Garry and Point Douglas.

For many years there had been in existence a trail running northwards from Upper Fort Garry along the high ground back from the Red River, past McDermot’s numerous buildings and thence over a crude bridge across Brown’s Creek and on to the Ross house and finally to Logan’s mill and house. When Drever’s and Bannatyne’s stores and the Royal Hotel were built they were also serviced by the same trail which was located several hundred feet east of the Main Road. [14]

Although surveyor Taylor had staked out a road allowance from Upper Fort Garry to at least as far as Sturgeon Creek in the mid-1830s, the road to the west was little more than a beaten track made by the Red River carts which wandered across the prairie with scant regard to survey lines. In the Settlement proper, a trail angled southwestwards from the kink in the Main Road just south of the present City Hall. Another trail ran northwesterly from Upper Fort Garry gate. These trails came together in the vicinity of Carlton Street and Portage Avenue in today’s downtown Winnipeg. From the juncture there formed, the cart road led westwards over the plains to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. The wye in the western trail can be found in the earliest maps of Red River Settlement dating as far back as 1818.

As time went on, the cart drivers coming from the west, instead of turning off on the trails to Upper Fort Garry and Point Douglas respectively, began to make a new trail between the arms of the wye, running easterly to cross the Main Road near where it intersected the south boundary of McDermot’s Lot 248. From this point the new trail carried on eastwards to where McDermot’s and Bannatyne’s stores (and later the Royal Hotel) were located.

Henry McKenney noted that this road from the west ran close by the edge of McDermot’s property so he and his partner, Schultz, approached McDermot and made him an offer for a plot of land on the west side of the Main Road and bounded on the south by the southern limit of McDermot’s lot. McKenney’s purpose was clear. He wanted to build his new store where the north-south and east-west travelways crossed. The deal was closed on 2 June 1862, and although nobody realized it at the time, the future corner of Portage and Main was thereby determined.

For the sum of £110 Sterling the partners got the ground they desired plus an easement to the river along the southern boundary of Lot 248. In addition, they were guaranteed for several years the right to purchase another piece of land with the right to occupy it in the meantime. £60 Sterling was paid in cash; the balance being covered by a ‘Note of Hand’ for £50 Sterling payable with interest at 6 per cent five years after date.

While the deed of conveyance put McKenney and Company in possession of a piece of land “therein very particularily described,” this document appears to have vanished. According to the 9 July 1862 Nor'Wester, the lot bought by the partners was two chains to the side (132 feet by 132 feet) but an old map of the area circa 1875 shows the McKenney lot as being diamond shaped with the east (Main Street) side being 3 chains, the south side also 3 chains, the west side (parallel to Main Street) 2 chains and the north side 2 chains with the west and north sides forming a right-angle.

If the appearance of the surrounding terrain is considered, it must be concluded that McKenney was very far-sighted indeed. The site was low and swampy, covered with scrub oak and poplar, and except for the fact that it was at the juncture of the western trail and the main north-south road, had little to recommend it. In the eyes of the old settlers, the worst feature was the distance from the Red River. “Nobody in their right mind,” they said, would even think of building over one-quarter of a mile from the river, at that time the only source of water.

McKenney commenced construction of his new store about a month after the land deal was completed. Architecturally, the building which stood where the CN Telecommunications offices are located at the corner of Portage and Main, was a ghastly example of Red River Primitive. Hargrave’s [15] description cannot be bettered:

“The house was a long two storey building, 80 feet long by 24 feet wide by 22 feet high, the ground flat of which was lighted by two large windows which, with the door, occupied one end, while the sides were windowed only in the top story which was used as a dwelling house. The proportions of the building, with its steep roof and side windows aloft, rendered it singularily like Noah’s Ark without the boat which usually accompanies the perfect toy. That it [the boat] would be absolutely necessary to complete the resemblance in spring was the firm idea of almost the whole population, who said that Mr. McKenney’s cellar would be filled with water and himself drowned out of his own house. The spring, nevertheless, passed and the structure escaped all damage from water amounting to anything more serious than inconvenience.”

“The house was erected in a perfectly isolated spot, and the hurricanes which sometimes blow across the plains, it was then imagined, would beat against the broad sides of the slightly-built edifice with such force as would reduce it to its native timbers. But although the house had sometimes to be supported by huge beams propped in considerable numbers from the outside, and was believed by its inmates to be by no means a safe abode on a stormy night, the winds proved as powerless to overwhelm, as the waters to sap, the experimental venture.”

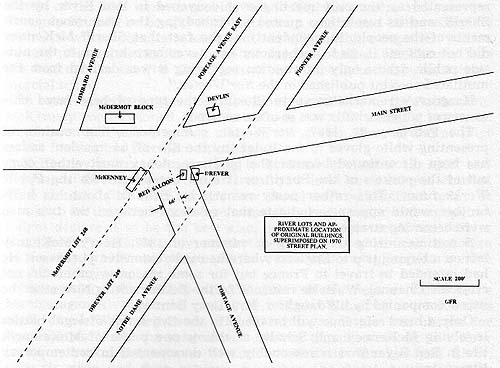

McKenney’s store was not built perpendicular to Main Street, as we know it today; the sides of his building were parallel to the old river lot boundaries. Its orientation can best be visualized by imagining an oblong box facing anglewise onto Main Street with its long sides parallel to the sidewalls of the CN Telecommunications and Childs Buildings. Judging by early photos and maps of the corner, McKenney’s store was apparently set ahead several feet from the Main Street property line. The peculiar configuration of the present day buildings at the corner of Portage and Main stems from the odd angle at which the original lots boundaries cut across the Main Road. McKenney started the trend by laying out his store the way he did and the reason why he turned the structure so that it faced southeasterly was that he wanted to have a good view of Fort Garry from his front windows.

McKenney and Company moved into their new quarters in the early part of November 1862, having disposed of their interest in the Royal Hotel to ‘Dutch George’ Emmerling, a German-American immigrant who had come to the Settlement some two years previously as an itinerant pedlar.

The prosperity that attended the new store caused some of the Red River Establishment to have second thoughts about the feasibility of its location. One result was a spectacular rise in the price of land near McKenney. The going price which had been 7 shillings and sixpence ($1.87 per acre) jumped to £25 Sterling per square chain ($1,250 per acre).

Drever now claimed that he had fully intended to build a new place on the Main Road long before McKenney but had delayed solely due to his inability to procure the necessary construction material. In the spring of 1863, Drever finally commenced erection of his store on the site of the Canadian Pacific Building. It was a substantial structure 50 feet long by 30 feet wide with walls 22 feet high, constructed with solid oak uprights 8 inches square filled with sawn lumber 4 inches thick. Unlike McKenney, Drever built his store facing squarely onto the Main Road.

The neighbors soon fell to quarrelling; Drever protested, according to Hargrave, [16] “that the store of McKenney and Company had been built so very close to his boundary on their side that the eavesdroppings of their Noah’s Ark-shaped store fell upon his land and would damage any house he might build close to the edge of his property, besides seriously interfering with his window lights.” On the other hand, McKenney contended that Drever’s building “cut off the view of Fort Garry which Mr. McKenney had formerly enjoyed from his front windows.”

All this sounds like picayune bickering, which it was, but the root cause of disagreement between McKenney and Drever went much deeper. Drever claimed that the west or Assiniboine trail, as it had come to be called, was located south of his store. In fact, the trail which was unsurveyed did run south of Drever when the spring thaw made the ground between Drever and McKenney a quagmire. On the other hand, when the land was dry or in winter, the trail went between the two properties.

On 9 April 1863, John Fraser was appointed Road Superintendent for the Middle District of Assiniboia. One of his first official acts was to call on surveyor Goulet to lay out a legal right-of-way for a road to the west. Nearly thirty years had gone by since Taylor had marked out the first western trail and the time had come to survey a new road in comformity with changed settlement and traffic patterns.

If the permanent location of the road lay south of Drever’s store then obviously he would have the preferred site. However, Goulet commenced his survey by setting a picket alongside McKenney’s store near an old fence that marked the southern limit of McDermot’s Lot 248. He then measured southerly for two chains (132 feet) at which point he placed a second picket and at the one chain mark drove a stake to denote the centre line of the new roadway. The road allowance was not tied in to previous surveys; it is doubtful if any of the old survey monuments, except the stone pillars at Fort Garry, were still in existence.

The next problem confronting the two men was the selection of the direction in which the new road was to run. The azimuth chosen is not definitely known but it would appear from a study of old maps that a compass bearing of approximately S 58 W was taken. This was reasonably close to the track of the old cart trail and became the location line of the embryo Portage Avenue as far west as today’s Spence Street.

The choice of a 132 foot right-of-way for the principal thoroughfares in the Settlement was not dictated by visions of eight-lane traffic arteries but was based on the mode of travel of the Red River carts. The carts tended to move in a rough echelon pattern which took up a lot of road. There were several reasons for this; a long single file of carts would have been vulnerable to ambush; by travelling in a random fashion they avoided following in the muddy ruts of the carts ahead and, finally, the Bois Brules were a gregarious lot who liked to migrate in closely-knit clusters.

While the surveying was in progress, Drever became anxious about the status of his lot and in particular what would happen to the building he was erecting. Fraser warned him to desist in his construction as his store would encroach on the new road and he would have to remove it. Since Drever’s lot was only 198 feet wide and its boundary lines bore about N 65 W, this meant that a 132 foot wide roadway running S 58 W and commencing at the Main Road would cut across the lot at such an angle that Drever’s building space on his Main Road frontage was severely restricted.

Drever refused to stop building and he was summoned to appear before Judge Black at the August assizes of the General Quarterly Court. The charge read: “The Public Interest vs. William Drever - an action brought against Drever for obstructing the public road by erecting certain of his buildings thereon.”

The complainant was Road Superintendent Fraser and as usual both parties to the suit conducted their own case. As might be expected, the evidence was conflicting. Drever’s witnesses maintained that the road should properly lie south of Drever while Fraser’s were equally positive that the correct place for the road was between McKenney and Drever, where Goulet had located it. J. H. McTavish, Chief Accountant of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Garry, deponed that Drever only held his land in leasehold. In spite of this testimony, Drever persisted in the fiction that he owned Lot 249 outright, that the land between McKenney and himself was his private park. He said that he wished to put this question to the Judge: “Can the public take possession of a man’s property any time they choose? I always understood that if my field was in use for less than 20 years I could reclaim it.”

After Judge Black and Drever had discussed this point at length, the Judge said: “It is somewhat irregular for you to put and for me to answer these questions ... but the proceedings will doubtless not be found fault with, since the object is to elicit information on an important point.”

Fraser and Drever then addressed the jury and Judge Black instructed them on certain factors regarding land tenure, the right of the public to the use of unsurveyed roads and trails, and advised them that the alleged encroachment had not been specifically defined. The jury retired and after being out for several hours found in favor of Drever but said that other evidence which they believed might be available might have reversed their decision.

Fraser asked for a new trial, claiming he could bring forward witnesses to testify that his surveyed road had been in use for 30 years. The Judge told him he must apply in writing for a new trial and said the case had some of the character of a criminal case and new trials were rarely granted in criminal cases.

Although Drever had won the first battle of the corner of Portage and Main, McKenney, as will be seen later, was to win the war.

The two continued to snarl menacingly at each other. According to Hargrave, [17] Drever complained that his neighbors “desired his destruction and had banded themselves to crush him,” while McKenney asserted that his business opponent was trying to “choke him off” and injure his site.

The disputants threatened court action, one against the other, and the 11 November 1863 Nor'Wester commented that: “The General Court of Assiniboia is to sit tomorrow week, Thursday, the 19th instant. The only case of interest, as far as we know, is that of McKenney and Drever about the house affair of which our readers have heard no doubt all they care to hear.”

This trial never came off, instead the Governor and Council of Assiniboia took a hand in the matter. Quoting the minutes of the Council for 19 December 1863; “Governor Dallas called the attention of the Council to the necessity that had arisen for getting the main public roads of the Settlement marked out in such a manner as to prevent disputes and litigation regarding the correct lines of these thoroughfares, and after some discussion the Council unanimously appointed a committee to mark out the roads under Dr. Cowan, Convener.”

At the meeting of 19 May 1864, “Dr. Cowan as Convener of the Road Committee, read their report to the Council; and it being afterwards intimated that one of the parties chiefly affected by the report (Drever and McKenney), if not both, had some additional evidence of an important nature which they wished to lay before the committee; the Council then referred the whole matter to the committee for further consideration and report.” At the meeting of 15 July 1864, “Dr. Cowan presented and read the report of the proceedings of the Road Committee. Unanimously adopted.”

Finally, at the meeting of 3 November 1864, the Governor and Council took the necessary steps to place these recommendations on a binding basis: “Whereas it is necessary for the due protection of the public as well as private interest, that the precise meaning and effect of the resolution of Council, of the 15th of July last, adopting the report of the Road Committee then submitted, should be duly declared, the Council in conformity with the recommendations of the committee unanimously resolved and enacted:

(1st) - That the line of the road to the Assiniboine Settlement [the present Portage Avenue] passing between Messrs. Drever’s and McKenney’s buildings and crossing Mr. Drever’s lot, remain as at the date of the report, and

(2nd) - that this road, while crossing Mr. Drever’s lot be one chain (66 feet) in breadth marked out so as to run clear of all buildings at the date of this report, and

(3rd) - That the main line of the road to the Assiniboine River at Fort Garry [the present Main Street], be marked out so as to run clear of all buildings at the date of this report, and

(4th) - That the public shall have the right to a two chain (132 foot) road crossing Mr. Drever’s lot leading to the Assiniboine Settlements [the present Portage Avenue], this width to be recovered by the public whenever the buildings encroaching thereon at the date of the report are required to be removed or at a specified period.”

Clause 3 of the above resolution indicated that the survey of a legal right-of-way for the Main Road was long overdue because buildings were springing up at random along the highway.

For the purpose of implementing Clause 4, the Council on the same day unanimously declared and enacted: “That eighteen years from the date of this Council [3 November 1882] shall be the period at which the permission for keeping up the encroaching buildings referred to shall cease, unless further extended by competent authority, and that, on the expiration of that period the public shall be entitled to a full two chain (132 foot) road crossing Mr. Drever’s lot leading to the Assiniboine Settlements [the present Portage Avenue] and that every obstruction thereon shall be removed as contrary to law.”

One would think that this would be the last chapter in the story of the corner of Portage and Main but such was not to be the case.

When the province of Manitoba was formed in 1870, a title in fee simple was granted to the legal occupiers of land who held their property in leasehold from the Honourable Company. This ruling applied to Drever’s Lot 249. Douglas [18] made some pungent observations on the situation which arose: “From the viewpoint of the layman the intent of these enactments by the Council seem perfectly clear. The owner of the land would be permitted to carry on but the highway was public property and in due time would be utilized as such ... nevertheless, in 1883, ten years after the City was incorporated, there still stood at the [southwest] corner of Portage and Main some dilapidated buildings encroaching right into the middle of the intersection. This encroachment measured 66 feet on Main Street frontage and had a depth of 279 feet along Portage Avenue. The bottlement created a traffic problem.”

Even as early as 11 September 1875, the Manitoba Free Press had commented: “A two chain road is a good thing, and the people who insist upon the Portage Road being where it is and being two chains wide are right and too much fuss cannot be made over it. But why not make just a little fuss about the same road being blocked up with wagons and things at the east end where it is only one chain wide.”

The final solution was that H. S. Donaldson, the registered owner of the land in 1883, made a deal with the Mayor and Council to transfer the property in question to the city for the sum of $35,000, the buildings to be removed within two months. Thus Portage Avenue at long last became 132 feet wide throughout its entire length.

Between the years 1863 and 1869, there was considerable building activity on the Main Road across from McKenney, Drever and Emmerling.

Begg’s “Rough outline of the Town of Winnipeg,” [19] dated 4 December 1869, shows Brian Devlin’s restaurant located on the southeast corner of the Portage and Main intersection (site of the Bank of Montreal).

The property on the northeast corner between the avenues now known as Portage East and Lombard (site of the Richardson Building) was largely taken up by a long two-story building constructed in 1866 (?) by Andrew McDermot and called the McDermot Block. The lower floor was divided into four equal sized stores and was generally referred to as McDermot’s Row. The upper floor, known as Red River Hall, had an outside entrance on the south end and was used as an assembly hall by churches, theatrical societies and other groups. In July 1868, a section at the south end of the top story was partitioned off for use as a printing office by the Nor'Wester.

In December 1868, O‘Lone and Lennon opened the famous Red Saloon on the 66 feet of disputed ground alongside Drever’s store which had temporarily reverted to Drever following the 1864 decision of the Council of Assiniboia.

It is interesting to note that in the mid-1860s, some of the old-timers at Red River were promoting the name ‘McDermot Town’ for the young village coming into being clustered about the corner of Portage and Main. By 1869, when Begg made his sketch, there were some 50 stores, houses, churches, hotels, saloons and various other buildings within a quarter-mile of the corner and the nascent metropolis boasted a population of almost 200.

The controversy over the location of Portage Avenue-to-be was only one of the many events in the life of the Settlement in which Henry McKenney was involved during his early years at Red River.

On 4 June 1862, McKenney and Company petitioned the Council of Assiniboia that: “the manufacture of soap be protected and encouraged by a large import duty” so that they could establish a soap factory on a competitive basis with American imports. The Council “laid over” the request. The Nor'Wester for 9 July 1862 carried an article by Ross headed “A Soap Factory” in which he was very critical of monopolistic practices and denounced the desired tax on imported soap, as it would be a grievous burden on poor people and be a benefit to none but McKenney and Company.

In the 30 August 1862 Nor'Wester, Ross had an editorial on “Opposition to the HBC” in which he noted that McKenney would send another expedition to get furs this year. In the same vein, under dateline 11 September 1862, he commented that “McKenney and Company had two boats up the Saskatchewan last year and intend to do the same this year.”

James Ross, a brilliant but erratic native of Red River, plagued with a fondness for liquor, who had defeated McKenney in the contest for Sheriff the previous year, was heading for a dramatic clash with the Governor and Council of Assiniboia. As a direct consequence of this blowup, McKenney was to embark on a part-time career which would eventually bring about an irrevocable split between McKenney and his half-brother John Christian Schultz.

During the autumn of 1862 great concern had been expressed throughout the Settlement over the possibility of Indian attacks such as had ravaged Minnesota that summer. At a meeting of the Governor and Council held on 30 October 1862, it was decided that “the best and only effectual means of meeting that danger, would be the presence of a body of British troops in the Settlement ... and that Judge Black be requested to draw a petition on behalf of the settlers generally ... praying the Government to afford the Settlement and desired military protection.”

Black composed the petition, but when a copy was sent to Ross for publication in the Nor'Wester, Ross took it upon himself to print instead, in the issue of 17 November 1862, a counter-petition. While it also asked for troops, it was primarily a diatribe against certain local officials of the Hudson’s Bay Company because of recent changes that had been made in Company policy regarding the settlers. It also represented to the Home Government that there was no justice to be obtained between man and man in the Settlement.

Ross may have been influenced in his decision to print his own version of the petition by his annoyance at the Council for ignoring a long and querulous letter he had written the previous May complaining about certain unresolved problems regarding the Postmastership and requesting an increase in salary.

The reaction of Governor Dallas and his Council to Ross’s action was swift and sure. At a special meeting on Tuesday, 25 November 1862, James Ross was summarily dismissed from all his public offices. At the same time, Henry McKenney was appointed Sheriff and Governor of the Gaol on the express condition of his immediately resigning his liquor license.

Ross erupted like a volcano. In a lead editorial in the 29 November 1862, Nor'Wester, he savagely attacked the Governor and Council under the heading: “The Council of Assiniboia - Undue haste - Thirst for revenge.” But he saved most of his venom for McKenney (the self-same man he had been complimenting a few weeks previously for bucking the fur trading monopoly of the Hudson’s Bay Company). “However shameful this part of the proceeding was, the other is ten times worse, if report be correct in having Mr. Henry McKenney as Sheriff. Alas! Alas! have confidence who will, we have none - not one iota. And we think it is an insult to the Settlement to put a man like McKenney over such as James McKay, William Inkster, Adam McBeath, A. G. B. Bannatyne, John Bunn and the like - men of talent and sterling principle whose families have borne the heat and burden of the day in bringing the Settlement to what it is. However, go ahead, Messrs. Councillors ... some of you will yet pay the penalty for last Tuesday’s vote.”

Ross began organizing open meetings through the Settlement for the two-fold purpose of securing signatures to the Nor'Wester petition, which some were now claiming was written by his publishing partner Coldwell, and of getting financial support for a scheme to send Ross to London to present his ideas on the status of the Settlement to the Colonial Secretary, the Duke of Newcastle.

One of these meetings was held in St. James parish with some forty people in attendance. The speakers, pro and con, included Ross, Fonseca, W. H. McTavish, Bannatyne, Louis Riel the elder and McKenney. McKenney’s remarks were briefly reported in the Nor'Wester with the sarcastic comment by Ross that McKenney was an outsider rewarded by the shrievalty for his zeal in supporting the Hudson’s Bay Company.

A curious aspect of the Ross affair was that the action by the Company which most incensed Ross was the decision by Governor Dallas that settlers bringing their produce to the Company would henceforth be paid, not in HBC notes but by credit on their HBC store account. If rigidly enforced, it would dry up the available supply of negotiable currency in the Settlement and would spell disaster for free traders such as McKenney. In short, McKenney, whom Ross was now calling a company toady might well be driven into bankruptcy by the company policy to which Ross so strongly objected.

Ross failed to raise enough money to pay his fare to England. So his petition, like that of Governor Dallas, was mailed to the Colonial Office. “Where,” as Hargrave put it [20] “the prayer of both was disregarded and the Settlement was abandoned by official men to whatever fate might turn up for it in the Chapter of Accidents.”

Hargrave, [21] in speaking of Sheriff McKenney said: “his principal work consists, I believe, in the collection of debts after judgment has been pronounced in the Courts.” Nevertheless, there were occasions in which the Sheriff had to apply force to apprehend a suspect and if there had ever been an execution in Red River Settlement, and the Sheriff could not have found anyone to act as hangman, then that unpleasant task would have been his responsibility.

Five days before he was appointed Sheriff, McKenney appeared for the last time as a volunteer defence counsel in the case of “The Public Interest vs. Louis Pruden,” involving a breach of the liquor laws.

The February 1863 sitting of the General Quarterly Court marked McKenney’s assumption of duties as Sheriff. The infamous case of the Reverend Griffith Owen Corbett was on the docket; the charge: “feloniously attempting to procure the miscarriage of one Maria Thomas,” an Indian girl whom it was also alleged he had seduced. The trial dragged on for nine days with all the sordid evidence being reproduced verbatim in the Nor'Wester.

Corbett was found guilty and sentenced to six months in the Fort Garry jail whence he was taken by Sheriff McKenney. Corbett was very popular among the English-speaking settlers and those of English-Indian parentage to whose religious wants he had attended. During his 13 years residence in the Settlement he had maintained a position of outspoken and uncompromising hostility to the Hudson’s Bay Company. Many of his friends claimed that the charge against him was framed to discredit him and that even if he was guilty the sentence was too severe.

On Monday afternoon, 20 April 1863, a gang of lawless elements led by James Stewart, broke down the jailhouse door and liberated Corbett. The next day Governor Dallas called for the establishment of an armed vigilance committee of responsible citizens to vindicate the law. William Hallett, an English-Indian, who had been given the post of Warden of the Plains following the death of Cuthbert Grant, waited on the Governor and his principal assistant, W. H. McTavish, to urge them not to raise an armed force to apprehend Corbett’s liberators.

While Hallett was holding the conference with the authorities, Sheriff McKenney and Constable Clouston went off armed and brought Stewart to jail. In arresting Stewart, who was schoolmaster in St. James, McKenney clearly showed that he was determined to carry out his sworn duties as Sheriff at the risk of unpopularity with a fair number of the citizenry and the possible loss of business in trade.

Early Wednesday morning, 22 April 1863, an armed rabble appeared before Fort Garry gate and demanded of the Governor that

(1) Stewart be released forthwith.

(2) Those connected with Corbett’s release be not punished.

(3) Henry McKenney be removed from his office as Sheriff.

Dallas peremptorily refused all their demands whereupon the mob forcibly entered the jail, which stood outside the walls of Fort Garry, and took Stewart away.

According to the Nor'Wester, “The Council subsequently issued a notice deploring the mob violence but took no further action. Apparently Governor Dallas did not wish to stir up strife between the various factions in the Settlement [English and French speaking] which might result in one side or the other calling on the warlike Sioux for assistance. The previous summer had been the year of the Sioux massacres in Minnesota and many of them were encamped north of the International boundary.”

The Nor'Wester for 22 July 1863 carried this notice: “We are authorized to state that the flag at McKenney and Company will for the future fly only on the arrival of mail and on Sundays. Parties at a distance will thus have notice of the arrival of the mail.” Hargrave mentioned that McKenney was very proud of his flagstaff. He may have flown his own house flag as did the HBC.

In July of that year, McKenney got a neighbor on the north when Emmerling, having found the hotel business profitable, decided to join the migration to the corner of Portage and Main. After buying from McDermot a lot adjoining McKenney, he commenced erection of a new hostelry which he named after himself. The building was 32 feet long, 22 feet wide and two stories high. Built of solid oak logs, it stood for nearly thirty years before being torn down to make way for the predecessor of the McIntyre Block.

McKenney left the Settlement sometime in the fall of 1863 and did not return until the next May. During his absence Schultz acted as Sheriff.

On 3 March 1864, Schultz bought an interest in the Nor'Wester and began taking an active part in the editing and management of the paper. The 10 May issue reported that McKenney had arrived on the International on 1 May and that the Sheriff would resume his duties at home. This issue also carried the first advertisement by McKenney and Company. Customers were advised that the proprietors had just received “English and other goods,” which indicated that McKenney may have been on a buying trip to England.

The Quarterly Court sitting of August 1864 was a ‘maiden’ one, there being no cases on the docket, so McKenney decided to emulate time-honored British custom by presenting the Judge with a pair of white gloves.

The late summer of 1864 saw the dissolution of the partnership between McKenney and Schultz. What caused the break-up is not known but it was probably due to Schultz’s desire to go into business for himself. In any event, the ex-partners remained on amicable terms for some time to come.

Advertising by the firm of McKenney and Company in the Nor'Wester ceased by 18 August and Schultz announced the opening of a new store for “staple and fancy goods” on 15 October. The title to the lot at the corner of Portage and Main, formerly registered in the name of McKenney and Company in Land Register ‘B,’ was transferred to Henry McKenney on 29 October 1864. McKenney re-commenced advertising in the Nor'Wester on November 9 as the sole owner of the business.

On 26 October 1864, the McKenney’s eldest daughter, Lucy, then only 17, was married at her father’s residence to 30 year old Linus Romulus Bentley, a well-known St. Paul businessman. Schultz printed a touching farewell to his young niece when the Bentleys left on 6 November on a wedding excursion to St. Paul. One has to admire the courage of the teenage bride setting out on a honeymoon trip of several hundred miles across the open plains with, as Schultz said, “every probability of encountering storms which last for days together, and perhaps bitter cold weather.”

Bentley, in partnership with two other St. Paul men, Harris and Whiteford, had begun a flat-boating service between Georegtown, Minnesota, and the Red River Settlement in May 1862, and their boats had carried a good deal of freight for McKenney and Company.

The 16 November 1864 Nor'Wester reported: “From Augustus McKenney, who saw many of the dry meat hunters at White Horse Plains, we have learned that many of the Sioux have gone across the Missouri to winter.”

The Augustus McKenney referred to in the above Nor'Wester article was probably Henry’s older brother who may have come to Red River Settlement to attend the wedding of his niece, Lucy.

On 7 December 1869, an Augustus McKenney married Nancy Catherine Settee, the daughter of a native Indian catechist, the Reverend James Settee, at Scanterbury on the Brokenhead River. Certainly, by any available family records, the bridegroom could not have been Henry’s brother, Augustus. Nevertheless, for two unrelated Augustus McKenneys to enter the picture would be remarkably fortuitous. One cannot rule out the possibility that this second Augustus McKenney was the result of a liaison between Augustus McKenney and an Indian girl during the McKenney brothers trading days in Minnesota.

At the 12 January 1865 meeting of the Council of Assiniboia, McKenney asked for an increase in his stipend as Sheriff. On the recommendation of Acting Governor Black, who said: “The Sheriff has discharged the duties of his office in a very efficient manner,” McKenney’s salary as Sheriff and Governor of the Gaol was raised to £40 Sterling per annum.

McKenney left on a trip to Canada in the last week in June 1865, and on 5 July of that year, Schultz and Coldwell dissolved partnership in the Nor'Wester with Schultz becoming sole owner and editor.

From 22 September 1865 until 27 January 1866, the Nor'Wester carried a large display ad by a Henry McKenney Jr. soliciting business for a “New Photo Gallery” using a “very superior instrument.” There is no further mention of Henry McKenney Jr. in the annals of the Settlement and he remains a rather mysterious figure. Although the Nor'Wester referred to him on one occasion as the son of Sheriff McKenney, the Nor'Wester was not the most accurate of reportorial media and the suspicion persists that he may have been Henry William McKenney, the son of Augustus McKenney and the nephew of Henry. Henry William McKenney was born at Amherstburg in February 1848, and is known to have been in Red River Settlement in the mid-1860s, receiving part of his education there. He passed through Edmonton in 1875 on an expedition to Rocky Mountain Fort eventually settling at St. Albert near Edmonton.

The rudiments of political organization started to evolve in the Settlement when it became increasingly evident that the days of absolute rule by the old Hudson’s Bay Company were numbered. A citizens meeting, so remarkable in many ways that it could only have been held at Red River Settlement, took place on 8 December 1866. This particular gathering was the result of a campaign by Schultz and some of his colleagues, including Thomas Spence, a recent immigrant from Canada. Spence was one of the more unusual of the minor characters who played a part in the stirring events preceding the birth of Manitoba. A land surveyor by profession, he was an ardent supporter of federation with Canada, and claimed to be an intimate friend of Thomas D‘Arcy McGee and other Canadian politicians.

Possessed of considerable writing ability, Spence edited the New Nation newspaper following the dismissal of Robinson as editor by Louis Riel in March 1870. He later wrote pamphlets urging immigration to the new province. He helped found the short lived Republic of Manitoba at Portage la Prairie in 1867 and he managed to intrude himself into the well-known 1870 portrait of Louis Riel and his council.

The 1 December 1866 issue of Schultz’s Nor'Wester printed the following ‘Requisition,’ dated Red River Settlement, 23 November 1866:

“To Henry McKenney, Esq.

Sheriff of Assiniboia.Sir: Whereas we are now on the eve of a great political change in the affairs of this country, we, the undersigned, hereby request you call a public meeting of the people of this Settlement, to be held in the Court House on Saturday, the 8th of December next, for the purpose of memorializing the Imperial Government, praying to be received into and form part of the Grand Confederation of British North America, and further express our desire to act in unity and co-operation with our neighboring Colonies, Vancouver Island and British Columbia, to further British interests and confederation from the Atlantic to the Pacific.”

The flowery style of the ‘Requisition’ is typical of the literary efforts of Thomas Spence.

To the ‘Requisition’ as printed, were appended the names of some 50 residents with the notation “and numerous others.” The most significant feature of the ‘Requisition’ however, was not its wording but the fact that the signers were representative of every ethnic, religious and social group in the community. Strangely enough, considering the text of the ‘Requisition’ and the results of the subsequent meeting, Americans such as Emmerling and O‘Lone were among the sponsors.

The following reply to the ‘Requisition’ was printed in the same issue:

“Public Notice”

“In compliance with a numerously signed requestion [sic] I hereby request and call a Public Meeting to be held in the Court House here Saturday, December 8th, 1866, at 10.30 A.M. Signed: Henry McKenney,

Sheriff of the District of Assiniboia,

November 30th, 1866.”

Schultz had a lead editorial praising the calling of the public meeting and expounding his views on the future political structure of the Settlement. He was strongly opposed to the establishment of a Crown Colony which he claimed would result in “bungling, waste and over-government,” and he was particularly critical of a suggestion emanating from London that a cadre of 50 officials, appointed by the Colonial Secretary, be sent from England to administer the affairs of any Crown Colony which might be formed. In short, Schultz wanted full and equal membership in the Canadian confederation. The wily Schultz foresaw (correctly, as it turned out) great financial and political advantages for himself in such an arrangement.

Hargrave [22] recounted in great detail the bizarre events of 8 December; unfortunately, the issue of the Nor'Wester which reported the meeting is missing.

In brief, ‘Dutch George’ Emmerling, a loyal American subject, apparently had second thoughts about joining Canada. On the appointed day he gathered together a number of his fellow-countrymen with the intention of proceeding to the Court House and advocating a policy of annexation to the United States.

Precisely at 10:30 A.M. “according to Mr. Spence or at an hour considerably before it, according to his opponents,” Spence and four other gentlemen appeared at the Court House and were admitted by Sheriff McKenney who declined chairmanship of the meeting and returned to his store. Resolutions were quickly passed along the lines suggested in the “Requisition.” Three rousing cheers were given for ‘Our Most Gracious Sovereign Lady the Queen’ and the assemblage promptly adjourned, its mission accomplished.

In the interim, ‘Dutch George’ and his cohorts were fortifying themselves against the chill December air in the comfort of his saloon, secure in the belief that Red River meetings never did start on time. Finally, Emmerling gave the order to head for the Court House and the Yankees, attended by a large retinue of thirsty and curious citizens, set out afoot and in carrioles in one of which ‘Dutch George’ had secreted a goodly supply of spiritous liquor for “gratuitous distribution among the supporters of the policy it was his intention to advocate.”

Halfway to Fort Garry they met the five jubilant Canadians who were on their way to the Emmerling House to drink damnation to the American eagle. On being informed that the public meeting was over, “the indignation of ‘Mine Host’ and his friends was almost too great to admit of adequate utterance.” A message was sent post-haste to Sheriff McKenney requesting the use of the Court House to hold a second meeting. “His permission was the signal for a hurried onset of the public in a vast mass from the village to the Court House, which on their arrival crowded to the doors ... The first resolve put to the new assembly was to the effect that the previous meeting had been an informality and a nullity and that all its resolutions should be rescinded as if they had never been passed.”

This resolution was adopted to the loud huzzahs of certain of the assembled multitude but when attempts were made to frame new resolutions favoring annexation to the United States, pandemonium broke loose with wordy brawls and fist fights erupting throughout the auditorium. Finally, “After some time had elapsed, the entire crowd ... sought hasty and uproarious exit ... with the view of continuing hostilities on a more extended scale outside. If such were their intention, it was abandoned, under the influence of the December wind. The patriots directed their steps towards the village where an orgy was instituted which ended about midnight with the demolition of Mr. Emmerling’s bar and the general destruction of his bottles and earthen-ware.”

Quoting Hargrave, [23] “The first meeting ... has been used for party purposes in Canada, and even, I believe, in England, where it has been represented as ‘the only meeting ever convened in Red River by the Sheriff’ and its resolutions quoted as embodying the unanimous sentiments of the people. Independently of the fact that Sheriff McKenney did not convene it, its true character has never been known to the outside public, whose only information regarding it was derived from the mutilated account published in the Nor'Wester.”

Hargrave’s remarks serve to illustrate the type of bare-faced chicanery of which Schultz was so often accused.

The 21 February 1867 Nor'Wester, commented: “The custom of presenting white gloves to the Judge [by the Sheriff] at ‘maiden’ assizes has been discontinued because the purchase money must either come out of the pockets of the Sheriff or it must be stolen from the Public Works fund.” This rather nasty remark by Schultz about his half-brother would appear to indicate that relations between the two men were becoming strained.

Sometime during the spring or summer of 1867, Henry McKenney left on a buying trip to England where he made extensive purchases. He had intended to travel to France but for some reason or other did not cross the Channel. When he returned to the Settlement in November he was accompanied by his daughter, Mrs. Lucy Bentley.

Only a brief reference will be made to the two series of legal battles involving McKenney and Schultz as this is one phase of McKenney’s life in Red River that is reasonably well documented in contemporary literature.

The first round of lawsuits arose from a dispute between the two men over the final closure of the books of McKenney and Company. The second came about as the result of F. E. Kew, the McKenney Company’s commission agent in London, England, suing McKenney and Schultz “jointly and severally” for settlement of his account with the firm.

As far as the story of Henry McKenney is concerned, the crisis came on 17 January 1868, when armed with a court order McKenney went to Schultz’s store and attempted to reason with Schultz to liquidate his share of the Kew debt without further delay. Schultz belligerently refused payment and when McKenney commenced to seize his stock, in lieu of cash, Schultz violently resisted. After a terrific struggle he was bound hand and foot and thrown into jail. This was yet another example of McKenney’s inflexible determination to perform his sworn duty as Sheriff regardless of any personal feelings. Schultz was promptly released from custody by a strong-arm squad led by his redoubtable wife. As in the case of Stewart, no action was taken against the jail-breakers.

Schultz never forgave McKenney for locking him up. Some 30 years later, Schultz, in an address to members of the Manitoba Historical Society, reminisced about his early days at Red River. While he spoke with feeling of many of his old friends and business associates, he never mentioned a word about his half-brother and one-time partner, Henry McKenney.

The spring of 1868 saw McKenney making plans for his most ambitious project to date, a sawmill on Lake Winnipeg to utilize the great stands of spruce timber available on its islands and along its shores. The waters of the lake were to provide fish to feed his loggers and sawyers. To equip his mill he bought a 25 H.P. steam engine and boiler complete with a saw carriage, lath saws and shingle machine together with a variety of attachments for a complete lumber business. McKenney was the first man to tap the timber resources of the lake basin on a commercial scale.

In order to provide transportation from his millsite to the Settlement, McKenney commissioned E. R. Hutchinson to build a sailing schooner. Hutchinson had served as first mate on the Anson Northup and as pilot on the Pioneer and the International.

McKenney returned from a trip to St. Paul on 12 August 1868, and the 25 August Nor'Wester had an item in its local news column entitled “The Launch,” “Mr. McKenney’s new vessel will be launched today. It is said to be the largest schooner west of Lake Superior and competent judges declare it to be the best also, reflecting great credit on builder Hutchinson.” Unfortunately, no sketches, pictures or dimensional data on the ship, which was christened the Jessie McKenney, appear to have survived the years.

Immediately after fitting-out, the Jessie McKenney set sail for the Manigotagan River, on the east shore of Lake Winnipeg some 40 miles north of the Winnipeg River. The Manigotagan locale was chosen for two reasons: first, the magnificent growth of spruce along the river banks and secondly, because of the fact that the Manigotagan River, with its wide and deep estuary, furnishes the finest natural harbor on Lake Winnipeg, well adapted to berthing a large sailing schooner.

The spot selected by McKenney on which to erect his sawmill was on Lot 10 of the present Manigotagan settlement. Remains of the stone foundation for McKenney’s steam boiler can still be seen just inside the west fence of the Catholic cemetery on Lot 10.

Manigotagan, which celebrated its centenary in 1968, is thus two years older than the province of Manitoba and five years older than the city of Winnipeg. Before McKenney’s arrival, the Manigotagan area was primeval wilderness.

The stream now known as the Manigotagan, was called Mainwaring’s River by Peter Fidler when he made his 1811 map of Assiniboia. Fidler was at that time the official surveyor of the Hudson’s Bay Company and William Mainwaring was Governor of the Honourable Company. The name Mainwaring’s River never received widespread acceptance at the local level. By the 1870s, Manigotagan, the expression used by the Indians in referring to the river, came into general usage. Manigotagan is a classic example of the greater sense of imagery displayed by the Indian, compared to the white man, in his choice of place names.

Manigotagan is the phonetic Anglicization of the Ojibway (Saulteux) phrase Mannuh-gundahgan which means ‘bad throat.’ Why was the name ‘bad throat’ chosen and what is its significance? Native folklore gives various explanations, a favorite one being that it meant “the place where the waterfall makes a noise like a bad sound in the throat.” According to this story, the name is based on an Indian legend concerning the eerie sound of Wood Falls, some three miles from the mouth of the river, when heard at a distance under certain conditions of wind and weather. “Bad sound in the throat” is either the queer honking sound made by a goose that has been shot through the throat or to the equally queer coughing sound made by a bull moose that has been shot through the throat.

Locally, the settlement was known simply as Bad Throat. In fact that was the name of the School District (now absorbed into the Frontier School District) although the Post Office has always been called Manigotagan.

During the autumn of 1868, the Jessie McKenney made two trips from Manigotagan with cargoes of lumber. Under “Local News” for 24 October, the Nor'Wester said: “Mr. McKenney’s vessel came in Friday the 16th and left on another trip on Tuesday last. McKenney’s sawmill on Lake Winnipeg promises to be a great success. He brought 55,000 feet of lumber with him.” Again, in the 7 November issue, “McKenney’s schooner returned from her second voyage on Saturday last. She brought 35,000 feet of lumber but only a few barrels of fish. As a general thing the whitefish catch on Lake Winnipeg has been almost a total failure this year.” The year 1868 was one of desperate food shortages at Red River Settlement; not only was the fish haul poor, the buffalo hunt was unproductive and the grain crop had been eaten by grasshoppers.

After her second trip the Jessie McKenney was frozen in for the winter near Lower Fort Garry.

Henry McKenney’s name keeps cropping up in curious ways in the Red River story. In the records of St. Paul’s parish church one finds that on 24 October 1868, the death took place of Henry McKenney Dahl, the infant son of Alexander Dahl. Dahl was a descendant of one of the Scandinavian woodsmen brought to Norway House in 1817 to clear the right-of-way for an ambitious road building project conceived by the Earl of Selkirk. Dahl had worked for some time as a clerk in McKenney’s store and he must have thought highly of his former employer to name a son after him.

On 29 January 1869, McKenney again submitted his resignation as Sheriff. According to the minutes of the Council meeting: “The Governor remarked that Mr. McKenney had always been very efficient and faithful in the discharge of his duties as Sheriff, and had, he believed, given general satisfaction; that considering his long experience in the office and the tact and ability he had employed in the discharge of his duties, he thought that they could hardly appoint a more competent person, but he had good reason to believe that the only condition on which he would resume office was a considerable increase in salary.

The Council unanimously concurred in the Governor’s opinion of Mr. McKenney’s efficiency as Sheriff. “Resolved by the Lord Bishop of St. Boniface and seconded by Dr. Bird: H. McKenney be re-appointed to the office of Sheriff and Governor of the Gaol at £100 Sterling per annum.”

The re-hiring of McKenney at double his former salary brought the predictable reaction from the Nor'Wester. Schultz had sold the paper to his crony, Walter R. Bown (a dentist at Red River) on 1 July 1868, and later Bown had hired Rollin P. Meade as editor. Under the heading “Waste of the People’s Money,” readers were told that while there was great distress and famine among the poor, the Council had seen fit to grant another £50 Sterling to, “that remarkably worthy official whose sole duty consists in being the right hand supporter of our no less worthy Judge during two or three days each quarter, and signing his name during the course of a year to a dozen or so legal documents.”

When the five-year note of hand for £50 Sterling, given by McKenney and Company to Andrew McDermot for the lot at the corner of Portage and Main on 2 June 1862, remained unpaid by 1869, McDermot took Schultz and McKenney to court at the February assizes. Schultz claimed he would be absent from the Settlement at the time of the trial and requested a postponement which the Judge refused. McDermot also sued for £15 Sterling ground rent but as this was not allowed for in the original agreement, judgment was in favor of the defendants.

In April 1869, James Stewart again came into conflict with the authorities and was fined for an offence against the liquor laws, although his fine was remitted under rather mysterious circumstances. A gang, allegedly made up of friends of his who were well-known town rowdies, unsuccessfully attempted to burn down the jail by throwing lighted faggots on the roof. As Governor of the Gaol, Henry McKenney, in the 1 May 1869, Nor'Wester, offered a reward of £50 Sterling for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the culprits but no one came forward to claim the informer’s prize and the incident was soon forgotten.

On 29 August 1869, fire totally destroyed a nearly completed house being erected by Andrew McDermot next to the Nor'Wester office. Fortunately the night was wet and windless otherwise a large part of the burgeoning village might have been wiped out. As a result of this fire a series of meetings was held by businessmen and other interested citizens which culminated on 11 September 1869, in the formation of the Winnipeg Fire Department, Henry McKenney being elected Fire Chief. The Hudson’s Bay Company donated their fire engine to the brigade; Andrew McDermot offered a lot on which to build a Fire Hall, and steps were taken to secure an adequate supply of buckets, hose and other fire-fighting equipment.

McKenney carried on his lumbering operations at Manigotagan the summer of 1869, although the actual production is not recorded, but with the coming of fall he decided to abandon the project. All his sawmill machinery was loaded onto the Jessie McKenney and brought to the Lower Fort where she was tied up to be frozen in for the winter. According to local tradition he sailed into Manigotagan harbor one evening, dismantled his mill and left hurriedly the next morning leaving behind only a large cast iron pot which he had used to render down sturgeon to make a crude lubricating oil for his machinery.

McKenney’s scheme to exploit the timber resources of Lake Winnipeg was an excellent one but there appears to have been one weak link in his plan of operations, namely the decision to use a sailing vessel to haul his sawn timber to market. The design characteristics of a sailing ship dictate a much deeper depth of keel than for a steamer of comparable bulk-carrying capacity. The shallowness of the Red, the silting-up of the mouths of the river at its delta and in particular, the rocky obstruction of St. Andrew’s Rapids, placed severe restrictions on the draft of a sailing schooner. The Captain of the Jessie McKenney was also faced with the difficult navigational problem of sailing his heavily laden ship upstream, on the narrow, winding Red, against winds which usually blew contrary.

Some ten years later, when the steam tug Lady Ellen went into service on the lake towing barge loads of lumber, the success of large scale lumbering was assured. Because he relied on sail rather than on steam to move his product, McKenney missed his chance to make a fortune.

A factor which may have influenced his decision to discontinue the Manigotagan sawmilling operation was that even at this early date he was toying with the idea of returning to the United States.

By the summer of 1869, Henry McKenney had spent ten years in Red River Settlement; he had become one of the leading businessmen in the community and, in addition, had filled for seven years an office of importance in the administration of justice. Consideration must now be given to the attitude he took towards the formation of the province of Manitoba.

McKenney had fulfilled his civil and judicial duties faithfully to the governing body at Red River but for reasons not wholly clear, when the critical time arrived, he favored annexation by the United States rather than union with Canada. He was the only native born Canadian among the more prominent Red River citizens who actively espoused annexation.

It would appear that McKenney’s posture began to harden as early as August 1869. In a letter from the Abbe Dugas to Bishop Tache [24] dated 28 August of that year, Dugas said, “People even go as far as to say that if he [Governor - Presumptive McDougall] presents himself as sent by the Canadian government to rule the country, he will be advised to take the road back to Toronto promptly. Mr. McKenney is, we are told, at the head of this move by the English.” Later in the same letter, “Messrs. McKenney and Bannatyne passed part of last night with the American consul; it is supposed that it was to discuss the state of the country.”

Following the seizure of Fort Garry on 2 November 1869, Louis Riel decided that he must take steps to broaden his power base and accordingly, on November 6, issued a call to the English-speaking inhabitants of Red River Settlement to nominate delegates to meet with the French speakers on 16 November, “to consider the political state of this country, and to adopt such measures as may be deemed best for the future welfare of the same.”

The representatives elected from the ‘Town of Winnipeg’ were Henry McKenney and Hugh O‘Lone (an American and proprietor of the Red Saloon; he was commonly known as ‘Bob’ O‘Lone). When the meeting was called to order, J. J. Hargrave gave McKenney a proclamation by Governor Mactavish to be read to the delegates. This was a type of quasi-civil function which McKenney, as Sheriff, was sometimes called upon to perform. The ‘English’ wanted the proclamation read at the beginning of the meeting but because of the vigorous protests of the ‘French,’ reading was delayed until the end.

McKenney’s career as Sheriff of Assiniboia came to a conclusion, for all practical purposes, on November 19, 1869, the last day of the last sitting of the old General Quarterly Court of Assiniboia. The final case is of more than passing interest: The Queen vs. Thomas Scott (executed on March 4, 1870) and three other men charged with aggravated assault on John Snow, their employer on the government road leading east from the Settlement.