by Gordon Goldsborough, Russ Gourluck, Randy Rostecki, Rob McInnes and Giles Bugailiskis

by Gordon Goldsborough, Russ Gourluck, Randy Rostecki, Rob McInnes and Giles Bugailiskis

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Link to:

Photos

Postcards in the early part of the twentieth century were frequently used as a convenient vehicle to carry greetings and brief messages to friends and family living in other parts of Canada or in other countries. As an alternative to telephone and telegraph, postcards were a relatively inexpensive way of communicating when the speed of transmission was not an issue. As an alternative to mailing letters, sending postcards permitted messages of only a few words – an advantage when the sender had little to say or was writing primarily out of a sense of obligation. The pictures, rather than the handwritten messages, were often the real highlights of postcards, especially before inexpensive cameras and film processing became common. They were intended to enlighten the recipients and perhaps to arouse some feelings of envy for the vacation travellers or proud residents who sent the cards. To achieve these results, postcards utilized images that showed off a community’s most attractive and photogenic features. One noteworthy aspect of this effort is that very few postcards views of Winnipeg show snow, an artful denial of the realities of several months of each year.

To see more Edwardian postcards of Winnipeg, and corresponding photographs at the same locations today, see the article “Greetings from Winnipeg: Views of a Changing City” in Manitoba History volume 55, June 2007. Preparation of this feature, and its corresponding print article, was made possible by a grant from The Winnipeg Foundation. |

Postcards were used in Canada as early as 1871, but people were permitted to write only the recipient’s address on them and nothing else. Finally, in 1903, the post office authorized “divided back” private postcards, where one half of the card provided space for the address, with space for a written message on the other half. The reverse side usually featured a photograph which, before true color photography, were often painted with colors resembling those of the original. Many companies got into the business, and the “golden age” of the postcard was at hand. In the years leading up to World War I, thousands of different postcards were created and millions were sent. Their broad subject appeal, their novelty in an otherwise black-and-white world of images, and their personal connection with the sender were all factors promoting their retention, long after the message they conveyed became irrelevant. Numerous postcards from early 20th century Winnipeg exist in collections around the world, providing useful – and in many cases, unique – views of the growing city.

It is understandable that these postcards presented views of the city’s heart, mostly focusing on buildings on major downtown thoroughfares. Until at least the 1950s, Winnipeg’s downtown was the community’s hub of commerce and entertainment. Two landmark department stores, Eaton’s and Hudson’s Bay, proudly stood a few blocks apart on Portage Avenue and were beacons that drew countless thousands of residents and visitors downtown every day. Hundreds of other shops along and near Portage provided even more shopping opportunities that couldn’t be found anywhere else in the city. The famed intersection of Portage and Main, with its nearby Bankers’ Row, Great-West Life, and the Winnipeg Grain Exchange, symbolized the early wealth and commercial prosperity of Winnipeg. Dining at Child’s, Moore’s, the Chocolate Shop, and dozens of other restaurants, or nights out at palatial movie houses like the Capitol, the Metropolitan, and the Odeon, ensured that Winnipeg’s downtown was a busy and exciting destination even when the retail stores were closed.

Implicit in these photos is the outward movement of Winnipeg’s population, especially during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Until then, most Winnipeggers lived, worked, and shopped in or near the core area of the city. There are few vintage postcards of the “suburbs” (as areas like East, North, and West Kildonan, Fort Garry, and St. James came to be called) not just because they would have offered relatively uninteresting views of streets and houses, but also because many of those areas were essentially rural at the time these postcards were produced. Some of the less desirable changes in Winnipeg’s downtown (exemplified by gone-and-not-replaced buildings) are the result of the movement of the city’s life blood away from its centre.

People do appear at a distance in some postcards, but their presence is clearly incidental and offers limited opportunity to study interesting features like clothing styles. Methods of transportation are also of secondary importance, but examination of the postcards and the current photos suggests several developments. The presence of cyclists (and even bicycle parking areas) are reminders that bicycles were a popular means of transportation in the early 1900s – and a technological step forward from the still-prevalent horse and buggy. Streetcars were a common sight on major Winnipeg streets until their elimination in 1955, evidence that most Winnipeggers relied on public transit (including trolley and diesel buses) until at least the midpoint of the century. The relative absence of buses in the current photos illustrates that the family car has replaced public transit as the primary mode of transportation (and reduced both the need and the desire to travel downtown).

But the primary focus of all of these images, old and new, is buildings, and seeing the same scenes from the same points of view with a century between them reveals an interesting mix of difference and sameness.

The most dramatic kind of difference is the elimination of a number of landmark structures and the failure to erect anything in their place. Nostalgia for buildings like the Royal Alexandra Hotel, the Empire Hotel, and the McIntyre Block can only be accentuated by the vacant lots that remain. Other buildings, like the quirky “gingerbread” city hall and the once-phenomenally-popular Eaton’s department store, have at least been replaced by the current city hall and the MTS Centre.

Other photos can remind Winnipeggers of landmarks that still stand (and are now protected by law) but have an uncertain future (including Upper Fort Garry Gate, the Union Bank Tower, and the Metropolitan Theatre).

Perhaps the most encouraging photos are historical buildings that not only are intact, but have exciting new leases on life. Wesley Hall is the heart of the University of Winnipeg. The Millennium Centre, the Birks Building, and the Walker Theatre exemplify how the heritage of buildings can be preserved and respected at the same time as changes enable them to thrive in the 21st century. Elim Chapel suffered a disastrous fire yet emerged strong and vibrant. The transformation of the Canadian Pacific Railway Station into the Aboriginal Centre of Winnipeg demonstrates not just the passing of railway passenger travel but the increasing pride and influence of First Nations people.

As much as some of these old-and-new pairings demonstrate visible differences in downtown Winnipeg, others provide an almost-eerie impression of sameness. Some views of sections of Main Street and the Exchange District are almost identical, despite the passage of over a hundred years. Although observers who equate progress with an ongoing cycle of demolition and construction will see these views as evidence of stagnation, heritage advocates will take justifiable pride in seeing the extent to which Winnipeg’s built history has been preserved.

Click each postcard to see, in a separate window, a modern view at the same place.

|

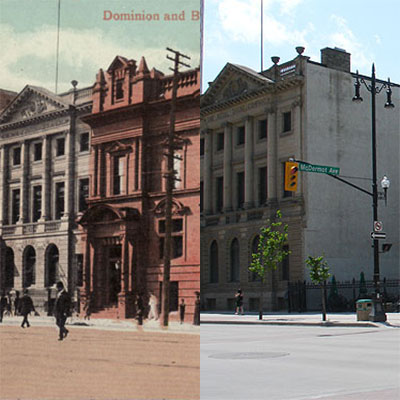

Dominion Bank, at the southwest corner of Main Street and McDermot Avenue (circa 1912) |

|

Union Bank Tower (left) next to the Leland Hotel and the “gingerbread” City Hall (circa 1912) |

|

Main Street |

|

Main Street north of City Hall, near present location of the Manitoba Museum. The McLaren Hotel stands at right. |

|

Wesley College, now the University of Winnipeg |

|

Osborne Village, looking south, at River Avenue |

|

Main Street underpass at Canadian Pacific Railway crossing, near the site of the Royal Alexandra Hotel at left (now demolished) |

|

Main Street south of Portage Avenue at York Avenue, near Empire Hotel (now demolished) |

|

Portage Avenue |

|

Birks Building on Portage Avenue |

|

Garry Street |

|

Broadway, seen from the Union Station on Main Street |

|

Hargrave Street at Qu’Appelle Avenue |

Winnipeg: Then and Now

© 2007-2010 Gordon Goldsborough, Russ Gourluck, Randy Rostecki, Rob McInnes, Giles Bugailiski & Manitoba Historical Society.

All rights reserved.

See also:

Greetings from Winnipeg: Views of a Changing City by Gordon Goldsborough, Russ Gourluck, Rob McInnes, Giles Bugailiskis and Randy Rostecki

Manitoba History, Number 55, June 2007

Page revised: 10 April 2024