|

|

|

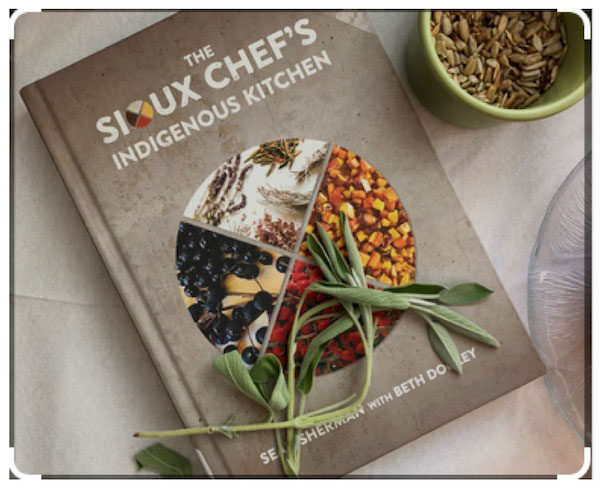

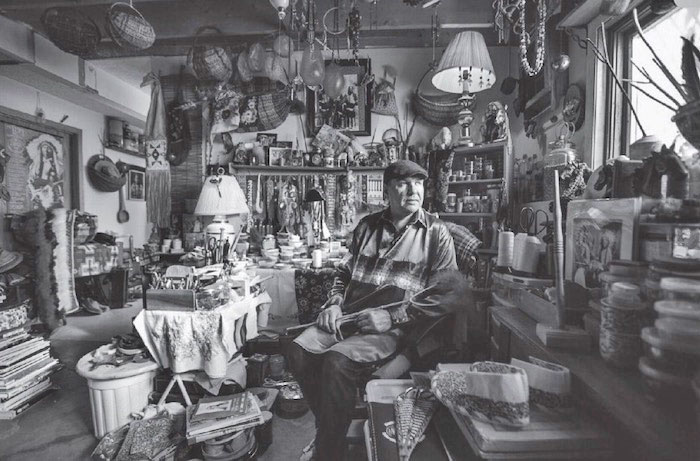

Part 7: Moving Forward 1.The Sioux Chef (Dakota Cuisine in Minneapolis) 2. Seeds of Knowledge (Eugene Ross & Foraging) 3. Self Government The winner of the 2018 James Beard Award for Best American Cookbook, went, for the first time, to a cookbook that was, finally, truly America.  The cookbook was also named one of the best cookbooks of the year by NPR, The Village Voice, Smithsonian Magazine, UPROXX, New York Magazine, San Francisco Chronicle, Mpls/St. Paul Magazine and others. Sean began hosting pop-up dinners around his adopted hometown of Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 2012, using foraged ingredients like sunflowers, milkweed and sage. After finessing his craft – and writing a successful cookbook – he finally decided to up the ante, opening Owamni, a modern Indigenous restaurant. Sean Sherman, grew up on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota and his restaurant is an extension of his philosophy of decolonizing cuisine, which involves learning how to cook the food of his Lakota ancestors. Recipes reflect his heritage as well as the natural history of our continent. His main culinary focus has been on the revitalization and awareness of indigenous foods systems in a modern culinary context. Sean has studied on his own extensively to determine the foundations of these food systems which include the knowledge of Native American farming techniques, wild food usage and harvesting, land stewardship, salt and sugar making, hunting and fishing, food preservation, Native American migrational histories, elemental cooking techniques, and Native culture and history in general to gain a full understanding of bringing back a sense of Native American cuisine to today’s world. Not you average Cookbook, or your average Restaurant. His establishment, which opened in July 2021 and won the James Beard award for best new restaurant the following year, is a rich education and delectable introduction to modern indigenous cuisine of the Dakota and Minnesota territories, His a vision and approach to food that travels well beyond those borders. It decolonizes cuisine. The 80-seat establishment, , offers anew version of fine dining.constitutes upscale fare. One won’t find ribeye steaks or deconstructed crème brûlées and other staples of “Americam Cuisine.” That has been replaced with selections such as wild game tartare topped with duck egg aioli and pickled carrots, maple baked beans and chewy wild rice dotted with foraged currants and rosehip. The food served at Owamni – the traditional Indigenous name for the site where the restaurant is located – is made without flour, dairy, cane sugar, pork or any other ingredients that were introduced to the North American continent after Europeans showed up in the 16th century. It has been an unqualified success, and is part of an important trend. According to the US Census Bureau, there were an estimated 24,433 Native American- and Alaska Native-owned businesses in 2018. The Sioux Chef team works to make indigenous foods more accessible to as many communities as possible. To open opportunities for more people to learn about Native cuisine and develop food enterprises in their tribal communities, we founded the nonprofit North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems (NATIFS) and are working to launch the first Indigenous Food Lab restaurant and training center in Minneapolis. Sources The Sioux Chef’s Owamni restaurant wows critics – The Guardian - Isabel Stone Sean Sherman, founding chef and co-owner of Owamni restaurant. Photograph: Nate Ryan/The Guardian  Eugene Ross harvests sage at Sioux Valley Dakota Nation. His grandmothers would spend summer and fall gathering food in preparation for winter. MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Eugene Ross is an elder at Wipazoka Wakpa Oyate, literally “Saskatoon river people,” the Dakota name for Sioux Valley Dakota Nation. The lower level of his home is filled with wicker basket of roots, stacks and layers of Dakota artifacts: framed photographs, clothing and beadwork. It’s a veritable Museum. A particular focus of Eugenes’s is food. The food that Dakota people have been gathering from the land for centuries. Not just the nature of the sustenance but, where to find it, and the knowledge of each items special properties. Seneca root he decribes as “Our Tylenol back in the day,” His extensive collection includes, wild turnips, peppermint, sage, sweetgrass, dried wild plums, rat root, elk medicine flower, wild onion and numerous examples of starches and fruit, vitamins and antioxidants, all from the grasslands. Many of us who, like myself grew up on a farm. Have walked by these plants without knowing what they were. After half an hour in the basement, Ross puts on a straw hat encircled with a wide band of maple leaves and leads me outside. He grabs a gardening fork, takes 10 steps and stops. He sticks his fork in the ground and digs up a few tiny plants nestled in the grass. The 15-centimetre plants have thin stems, white flowers and jelly-bean-sized bulbs. I don’t know the plant. “Wild onion,” Ross says. I give it a sniff. It smells like … onion. I had bought pipe tobacco from a store in Brandon, and though I didn’t tell Ross I had it, he must have noticed the pouch poking out of my shirt pocket. “You can put some tobacco here,” he tells me, pointing to the hole left after removing the onion. I take a pinch and sprinkle it on the ground. I’m not sure I’m doing it right, but Ross doesn’t correct me. It feels like I’ve climbed a step on the mountain, paying respect for what the land provides. I am learning. Ross knows the plants of the Prairies. He knows the history. He tells me his grandmothers, the “keepers of the lodge,” spent all summer and fall gathering food in preparation for winter. “They had their own system that never failed them,” he says. He is now the lodge keeper. The people living near him “don’t have any Indian things in their houses,” he says. When they want wild sage, they ask him to pick it instead of learning how to do it themselves. It’s been a challenge, he admits. Sarah Carter, in her book Lost Harvests, writes about the useful knowledge that First Nations people had: “Their highly specialized empirical knowledge of nature approached a science. They were aware of the vegetation in their environment, and they knew when and how to harvest it. They were much better informed on rainfall and frost patterns, on the availability of water, and on soil varieties than settlers from the East and overseas who were to follow.”  Eugene Ross’s basement is a trove of Dakota treasures and artifacts. MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS  Ross unties a willow basket full of braided wild turnips in his basement. MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS LEAH HENNEL / THE NARWHAL  Jay Whetter is a Canadian farm journalist with 25 years of experience. Jay grew up on a farm near Dand, Man., and lives in Kenora. Jay is on the board of Science Writers and Communicators of Canada and is a member of the Canadian Farm Writers Federation, which he says are rich and rewarding communities of communicators. There are many aspects to reconciliation. It begins with understanding and acknowledging history, understanding colonialism, and working together to overcome issues stemming from the past. On another level, reconciliation must involve changes in governance, responsibility for public policy, and movement on Land Claims. Historically, First Nations in Canada have been subject to the Indian Act and policies of the Department of Indian Affairs, which has led to detrimental impacts and interference with the progress of First Nation communities. Two Canadian Dakota Nations have made history recently. Sioux Valley Dakota Nation - Self Government The Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, as a result of the passage of Bill C-16, followed by passing a similar statute by the Province of Manitoba, became self-governing on July 1, 2014. This will provide Sioux Valley with the opportunity to remove itself from the constraints of the Indian Act by beginning to pass laws, and be a recognized government by Canada and Manitoba. By creating its own governance based on Dakota traditions, SVDN will be recognized through agreements negotiated with Canada and Manitoba as a government pursuant to the SVDN Constitution of the People. These agreements were negotiated over 21 years with the contributions of many Elders, members and leaders. The agreements were initialed by the negotiators on June 28, 2011 to end the negotiation process, and on October 4, 2012, a majority of eligible voters from SVDN voted in favor of accepting the SVDN Governance Agreements. This approval established SVDN as the only recognized First Nation government east of British Columbia and west of Quebec. Furthermore, SVDN is the only Dakota Nation Government, the only First Nation Government with a Tripartite Agreement with a province in Canada, and one of only three single First Nation governments with recognized law making jurisdiction. This will provide Sioux Valley with the opportunity to remove itself from the constraints of the Indian Act by beginning to pass laws, and be a recognized government by Canada and Manitoba. Adapted from the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation website: https://svdngovernance.com/governance/a-self-governing-dakota-nation/ Whitecap Dakota First Nation - Treaty People On May 3, 2023 CBC News reported that Whitecap Dakota First Nation signed an historic treaty with Canada. Dakota members were formally (and finally) recognized as Indigenous peoples in Canada. This comes after a decade of negotiations and centuries of being unrecognized as Indigenous people of this country. The First Nation in Saskatchewan says it's the first Dakota nation to sign a treaty in Canada. "It's just a step at a time, but this is a very positive day for our ancestors, our people and our future generations," said Whitecap Dakota Chief Darcy Bear in an interview, minutes after he signed the document in Ottawa. The agreement not only acknowledges and describes the First Nation's inherent right to self governance, but also formally recognizes the community as Indigenous people of Canada under the constitution. When treaties were signed in the 1800s in Saskatchewan, Whitecap's chief was there, but wasn't invited to sign. The First Nation has been unceded until Tuesday. "When you're not being recognized in a country you helped create … it was totally wrong. We should have never been denied that right," he said. "To us, it is reconciliation." The agreement makes Whitecap Dakota the first and only self-governing First Nation in Saskatchewan. The First Nation has been negotiating with Ottawa for self-governance since 2009. It already has autonomy in areas such as land management and membership, but this agreement now allows the community to move away from the Indian Act as much as it wants. Source: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/whitecap-dakota-first-nation-self-governing-saskatchewan-1.6829736 |