|

|

|

|

Part 3: The

Transition Period

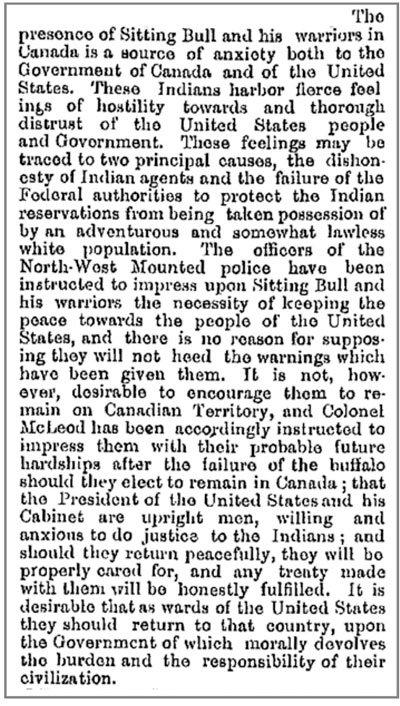

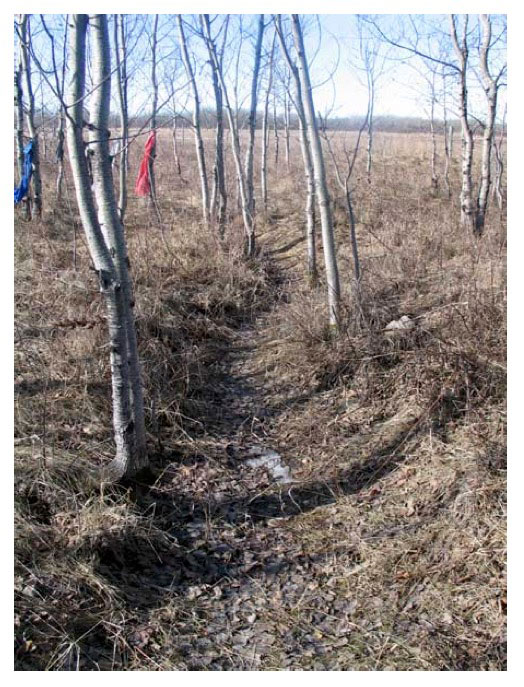

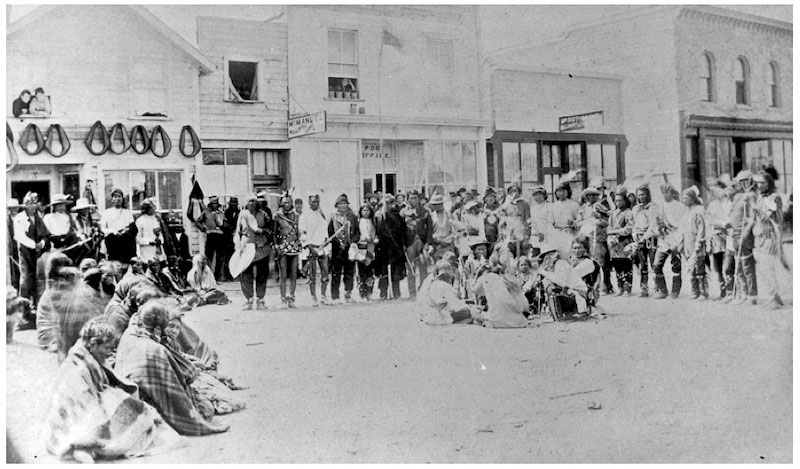

1.The Refugee Debate 2. The Dakota Fortified Camps of the Portage Plain 3. The Dakota - Nakota Wars 4. George Custer and the 7th Cavalry 5. Indians At The Fair 6.The Transition to Reserve Life Canada, in 2023, is facing a refugee problem. A lot of people fleeing unhealthy and dangerous conditions in their home country want to come here. We are trying to understand and sympathize, but were not sure how to control the situation. The following excerpt from a newspaper report from 1878 brings out some points about that refugee problem. The report begins by an attempt to understand the position that the Dakota found themselves. It is partially correct, but seems to omit the important fact that the US Army did much more than fail to protect the Dakota from “dishonest” Indian Agents and “somewhat lawless” settlers. The policy and the actions played righ into those hands. So what starts out as sympathy quickly turns into caution. Then it turns towards the absurd. To say that the government of the US was “anxious to do justice”, was a bit of a stretch. It ends with the same old mantra about the “responsibility of their civilization.” The same devotion to this “responsibility” led us in Canada, to the Indian Act and Residential Schools. What it means, that although we followed different paths, the US and Canada shared similar colonial / Euro-centrist outlook.  Manitoba Free Press - March 6, 1878 Excerpts from a document prepared by Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Citizenship Near the marsh that borders the southern edge of Lake Manitoba, north of High Bluff and Poplar Point, are three circular features known as the Flee Island, St. Ambroise, and St. Marks entrenchments. The eastern Dakota (Sioux) of Minnesota traditionally built ćunkaśke (pronounced “choonkashkay”)—wooden palisades, piles of stones and earthen entrenchments—around their camps and villages for protection against the elements, wild animals, and potential enemies. One group was even referred to as the Cunkasketonwan: Nation of the Forts. These entrenchments are the remains of fortified campsites, usually consisted of pits and trenches surrounded by earth embankments, which were placed around campsites for defensive purposes. The entrenchments of the Portage Plain are comparatively recent examples of a tradition dating back at least 1000 years in North America, and found over a vast portion of the continent. Between 700 AD and the arrival of Europeans, huge areas of the Ohio, Illinois and Mississippi river drainages were occupied by people who based their livelihood on the raising of domesticated plants. They practised a religion that drew much of its inspiration from Mexico and Central America. These people lived in villages and towns dominated by flat-topped pyramids that were surrounded by entrenchments and fortifications. Archaeologists call this “Mississippian” because many sites occur along that river’s banks. Farther to the west, along the Missouri River, evidence has been found of a contemporary culture which appears to have been significantly influenced by the Mississippian. Referred to as “Plains Village” by archaeologists, these people are also horticulturalists who supplanted their diet with wild plant food and the proceeds of seasonal bison hunts. They surrounded their villages with trenches and stockades. The practice of fortifying villages was very much alive throughout the upper Midwest at the time of European contact. It is believed that most of the Mississippian peoples and Plains Villagers were Siouan-speakers. Defensive fortifications vary considerably in terms of their size and complexity. The Flee Island trench is nearly circular with a diameter of about 37 metres. The circumference is interrupted by several unexcavated gaps. In 1972, the depth of the trench varied from 0.3 to 1 metre, and there was a semi-continuous bank of earth around the outside. Inside the enclosure were a number of deeper pits located close to the trench. The remnants of one such ćunkaśke, known as the Flee Island Entrenchment, are located in the area near a marker at this site.  Flee Island Entrenchments (April 2010) Source: Gordon Goldsborough - Historic Sites of Manitoba Designated a provincial historic site in 1954, a commemorative monument was erected here in 1991 by the Manitoba Heritage Council. Site Coordinates (lat/long): N50.10549, W98.15575 The St. Ambroise entrenchment is 108 metres in diameter. It is a continuous trench, unlike the one at Flee island, but has similar interior pits and an earthen embankment around its outer edge. There are two pits outside the - their actual functions might have been as been wells or observation posts. The St. Marks Entrenchment is different. It is approximately 100 metres north to south and 90 metres east to west. At irregular intervals along the trench are found circular stone features, some of which have deep pits behind them. These circular heaps of stones were originally piled atop one another to form a barricade in front of the trench and pits. Local residents have referred to them as “ramparts.” Ten such ramparts were distinguished easily in recent years, although more of them may have existed originally. Defensive trenches and fortifications were part of Dakota culture for some time. Explorers and traders often mention them. Some were well-planned preparations, other might be hastily built in response to and emergency. The Reverend Mr. Samuel Pond and his brother Gideon were the first missionaries to reside permanently with the Dakota. Samuel Pond discussed the Dakota customs and traditions in a paper entitled “The Dakota or Sioux as They Were in 1834.” In this work, Pond describes the practice of entrenching as he had observed it: When a war party unexpectedly found itself in the presence of a strong force of the enemy and an attack was apprehended, entrenchments were made by digging pits in the ground, the earth being loosened up with knives and thrown out with the hands. They did not dig a long trench, but separate holes, each one selecting the place that best suited him. If they had time to finish their pits they dug them three or four feet deep, and if they found easy digging they did not require very much time and it was marvelous to see how rapidly they would throw out the earth. The inhabitants of villages prepared in a similar way for defense against an apprehended attack from a war party, although when women and children were to be protected, the pits were made large enough to accommodate families, the non-combatants sitting securely in the bottom of the trenches while the bullets whistled over their heads. I once passed a large camp of Indians in the evening and saw them dwelling quietly in their tents, but on visiting them again the next morning I found them all hidden in the ground. They had been alarmed in the night, and before daylight they were where hostile bullets could not reach them. It is obvious, in light of the recent descriptions of them and from the very brief historical account of their construction, that the Flee Island, St. Ambroise, and St. Marks entrenchments were built under circumstances similar to those described by Zebulon Pike and Samuel Pond. The Origins of Flee Island Early one morning during the first week of May 1864, a Dakota fishing camp on Lake Maniotba camp was attacked by Chippewa bounty hunters believed to have come from Red Lake, Minnesota. The Red River Settlement’s newspaper, The Nor’-Wester, reported this raid and noted that the Dakota were “busily engaged in fortifying their present encampment” by “digging rude earthworks and rifle pits.” Tradition locates the first attack on or near Bluebill Bay, 25 km north of High Bluff. This district of the province and the subsequent fortified or entrenched camp built by the Dakota are called “Flee Island” in reference to the Chippewa raid and to the necessity of the Dakota to flee for their lives. Following the initial attack, the Dakota, who were carrying all their possessions with them in wagons, probably formed a defensive camp wherein the wagons were placed in a circle above trenches that had been previously excavated. Behind them were dug pits in which the women and children could conceal themselves for protection, according to the descriptions of Pike and Pond. It is most likely that the Flee Island cunkaske relates to the first attack by the Red Lake Chippewa. Seven years later, in 1871, when R.W. Hermon conducted the first legal survey of the Portage la Prairie region, a large wooded area comprising the west half of Section 35, Township 13, Range 6 West was noted as “Flea Island.” This location is 1 mile west and 3 miles north of the Flee Island Entrenchment, midway between it and Bluebill Bay. For more Infprmation: BADERTSCHER, P. 1984-85 Lake Manitoba Sioux Entrenchments: Inscription, Brochure and Report. Manuscript on file, Historic Resources Branch. Winnipeg. GARRIOCH, Rev. A.C. 1923 First Furrows: A History of the Early Settlement of the Red River Country, Including That of Portage la Prairie. Stovel Company, Limited. Winnipeg. GETTY, I.A.L. and D.B. SMITH 1978 One Century Later: Western Canadian Reserve Indians Since Treaty 7. University of British Columbia Press. Vancouver. GOLDBERG, H. 1972 The Lake Manitoba Sioux Indian Entrenchments. Manuscript on file, Historic Resources Branch. Winnipeg. HARGRAVE, J.J. 1871 Red River. John Lovell. Montreal. HILL, R.B. 1890 Manitoba: History of Its Early Settlement, Development and Resources. William Briggs. Toronto. NOR’WESTER 1858-1869 Microfilm Legislative Library. Winnipeg. PIKE, Z. 1872 Pike’s Explorations in Minnesota, 1805-1806. Minnesota Historical Society Collections 1, pp. 318-416. POND, S. The Dakotas or Sioux in Minnesota as They were in 1834. Minnesota Historical Society Collections 12, pp. 319-501. WILLEY, G.R. 1966 An Introduction to American Archaeology, Volume I: North and Middle America. Prentice-Hall, Inc. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. The 1830’s was a period of intense warfare for the Dakota and Nakota and much of the conflict centered around Roche Percee, Sask. At the heart of this war was a conflict over some strange rock formations found along the Souris and one of its tributaries called Short Creek. This portion of the Souris River was considered a holy area by both Nations. The valley features mushroom shaped pillars (called Hoodoos). One of the pillars is perforated by a large hole and so the name “Roche Percee”. The Indians in the past believed the place sacred and when passing the hoodoos rubbed vermillion on them or put gifts of beads, tobacco, etc. in the caves in the area.  Until a few years ago the Dakota considered its remains sacred. One of the rock remnants in this old ruin is believe to have an astronomical significance. On the rocks carvings (petroglyps) of men, deer, fish, turtles and rough sculptures of tents and stars appear to have been done by the Dakota, at least L. A. Prudhomme believes they are indicative of Siouan style. Some of the carvings are of horses so we know that at least some of this work was done by Plains Indians who only acquired horses in the 1700’s. The contest between Dakota and Nakota for mastery of these strange canyons has never been fully settled. Legend has the Nakota stoppinging at Roche Percee every Spring and Fall to pay homage and Chief Ochankugahe, but in 1738 La Verendrye called it a Dakota Shrine and Roche Percee residents today refer to it as a former Dakota Shrine. A Northwest Mounted Police report in the previous century is alleged to refer to Dakota Shrines in the area In the early part of the twentieth century the Dakota came back to Roche Percee to hold dances at their shrine. This shrine on the side of the valley was destroyed when coal mining operations came too close to the edge and the shrine was buried by tons of earth. In 1830 a large band of Nakotas marched west to attack the Dakota in Souris Valley near Roche Percee. They sent warriors ahead to scout the area. As the scouts approached La Rivieres des Lacs they climbed a large hill and found a Dakota sentinel asleep whom they killed. The main Dakota Band soon found their murdered sentinel and withdrew to Roche Percee. The Nakotas moved up the Souris Valley to attack but the Dakota were victorious. The hill where the sentry was killed is still called “The Hill of the Murdered Scout” and readily seen from Highway 9. In 1831 the Dakota returned the Nakota attack moving east down the Souris River into Manitoba. They turned north where they met a Metis Buffalo Brigade returning from the Moose Mountains. The buffalo hunters, as usual, formed a circle with their cars and held off the attackers. This attack took place to the west of Oak Lake. In the same year, Dakota war parties forced the forts at the mouth of the Souris to close. Shortly after these battles, a recurrence of smallpox hit the Nakota very hard. That and a migration westward ended the conflicts. Suppressed by a lingering fear of military retaliation, a fragmentary version of the story has been kept alive by the descendants of a Dakota Indian who fought in the Battle of Little Bighorn. Sioux Valley Dakota elder, Moses McKay, knews a bit about that and in 1989 revealed another fragment of the story. Mr. McKay described how his grandfather advanced toward Custer with gun blazing. The lieutenant colonel retreated, his pistol empty. Then he fell backward into a gully. Nobody will ever know which bullet killed George Custer, but Mr. McKay believes it may have come from his grandfather’s gun. His daughter, Sheila Beardy had heard some of the Custer story from her grandmother but she always assumed that her great-grandfather was merely a witness to Custer’s death. Even in the family, some details of the story have been kept secret. The bloody death of Custer and the 7th Cavalry—the last great victory by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse and other nineteenth-century Indian warriors—became a legend in popular United States history, but the “Indian” version of the battle, however, was rarely told. Mr. McKay and his wife Eva, first heard the story from Mr. McKay’s mother, who heard it from her father, a quiet man known as Wakpa Iyewege (Crossing the River) who fled to Manitoba after the battle in Montana in 1876. The reality of the Custer battle and all battles was in no way like the Hollywood version of the such battles. battlle. Mr. McKay reminded us that, “You see them yelling on the TV, but nobody ever did that,” he says. “They stayed quiet.”  For many decades the conventional history of the Battle of Little Bighorn was shaped in a heroic mode in paintings, and by Hollywood. Custer’s troops, outnumbered by the Indians, were killed by arrows in the early stages of the battle. Then the Indians picked up the guns of the fallen soldiers and used them to finish off the soldiers. Mr. McKay’s grandfather, who was accompanied by a “blood brother”—a close friend who had persuaded him to join the battle—eventually found himself confronting Custer. Both fired their guns at Custer. As the officer fell dying, McKay’s grandfather grabbed the reins of Custer’s two horses. He knew that the top army leader usually owned the fastest horses. Those were the animals that helped him flee to Manitoba. But afraid that military investigators might recognize the horses, he traded them for two slower animals after he reached Manitoba. It is widely accepted now that participants in the Custer Battle were reluctant to tell their stories of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. There was the danger of repercussions. Moses McKay recalled : “My mother thought that they might pick us up and put us in jail,”. “The old people were scared of the white men for a long time after the battle.” It is impossible to verify the story of Custer and Moses McKay’s grandfather. Historians have never been certain of the identity of person or person who killed the famed general and afterwards, several Indians claimed to have been responsible. Yet the story told by the McKays has the ring of truth to it. In several of its details, the story is supported by physical evidence. Custer was killed by two bullets and he died on the slope of a hill. He had two horses at the time of the battle and many of the Indians did flee to Canada afterwards. Checked with facts that are known the circumstances of the story related by the McKays are quite conceivable. Still, there is a widely-held belief that the Indians didn’t know who they were fighting until long afterward—although clearly some of them knew Custer because he had visited their camps, both a peacemaker and a warrior. And many Indians later claimed that they killed Longhair. All of this whiteman history matters not to Sheila Beardy. She has no doubts about her grandmother’s version. “My grandmother doesn’t lie.” Source: By Geoffrey York, The Globe and Mail, Tuesday, November 14, 1989 Sioux Valley, Man. Indians at the Fair  Aggressive efforts to deny, disparage and eradicate all expressions of Aboriginal culture as part of the process of assimilation were in direct conflict with both Aboriginal determination and white settler’s interest in displays of the culture. So while the Governments, as represented by Indian Affairs sought to outlaw all such displays and celebrations. Settler communities invited citizens from nearby reserves to fairs, parades and such celebrations. Sources The Imaginary Indian: The Image of the Indian in Canadian Culture Paperback– Jan 1 1992 by Daniel Francis (Author) Arsenal Pulp Press, Vancouver, BC 1885 was a busy year in the Souris Valley. Riel runners arrived along the Souris. They came from Batoche in Sask. and tried to persuade the Dkota in Oak Lake and the Turtles to support Riel in the coming Sask. Rebellion. Although the Dakota in the Turtles performed a few war dances and frightened the settlers in older Deloraine they remained out of the fray. The Northwest Mounted Police patrolled the Canadian-United States border into Manitoba. They were checking for any illegal influx of Dakota or American outlaws. They also checked established Dakota villages for signs of unrest or support for Riel. In 1888 the Dakota were still nomadic and many of them roamed from Devils Lake, North Dakota to the Turtle Mountains and still further north to Oak Lake. Father Gaire, the first priest at the Grande Clariere Parish, met and fed many of these people as they wandered about the country. The period between 1862 and 1888 had been a difficult one for the Dakota. In the United States they had been attacked repeatedly by the Army, usually for trying to protect their homeland, and sometimes when they were completely innocent of any wrongdoing. In Canada they were occasionally refused food by the Canadian Authorities or given very short rations. In addition the Canadian Indians attacked them on several occasions. But their belief in an unspoken alliance with British continued. In 1874, during the American Indian wars a traveler who left St. Paul for Fort Garry was warned by the Americans not to do so as the Dakota were on the warpath. But when the traveler met the Dakota he simply ran up the Union Jack and the Hudson Bay Flag and was allowed to continue his journey north. The hard times left the Dakota and others in a weak bargaining position, to say the least, when negotiations about Treaties and Reserves took place. Although there was a show of consultation, and small concession were made, They were often forced by circumstance to accept much less than they needed to prosper in the new reality. A word about diet. An early report focused on a troubling death rate on reserves. The Dakota were often ill and deaths were attributed to consumption and scrofula. The Agents believed the Dakota were weakened by the sudden reduction in the amount of meat in their diet. In 1885, eleven out of eighty-five heads of families at Oak River died, as did seventeen children under the age of three. |