|

|

|

Part 2: The Dakota Experience in Manitoba

|

1. Pre-Contact

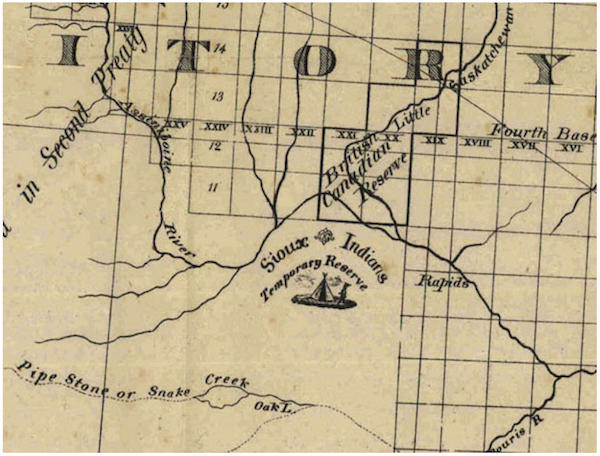

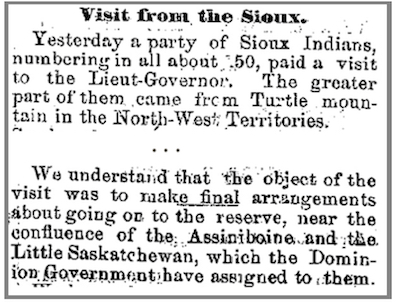

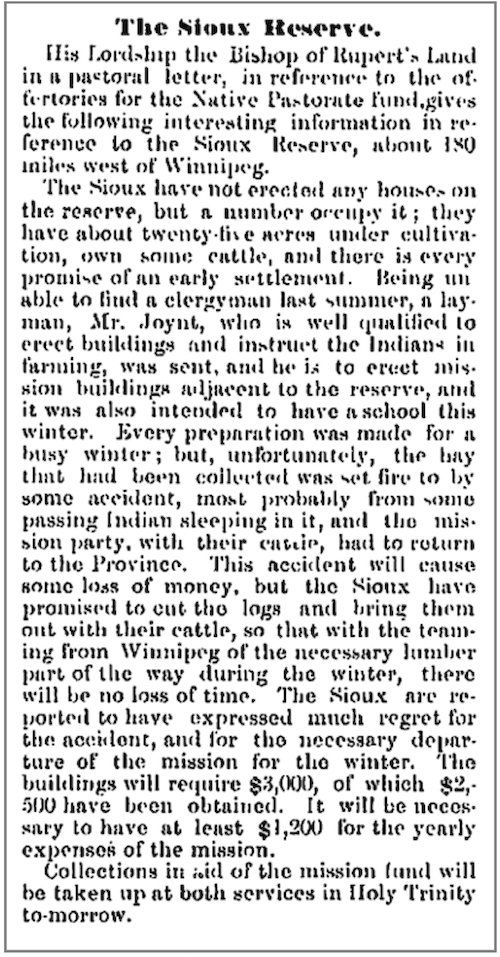

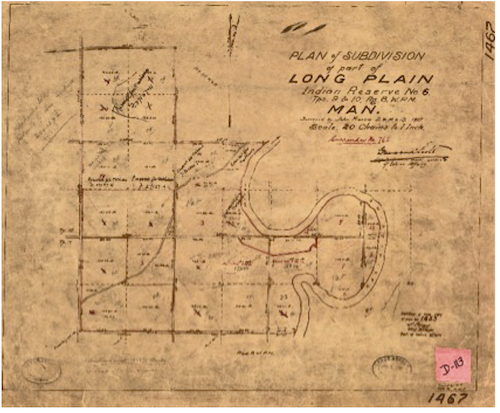

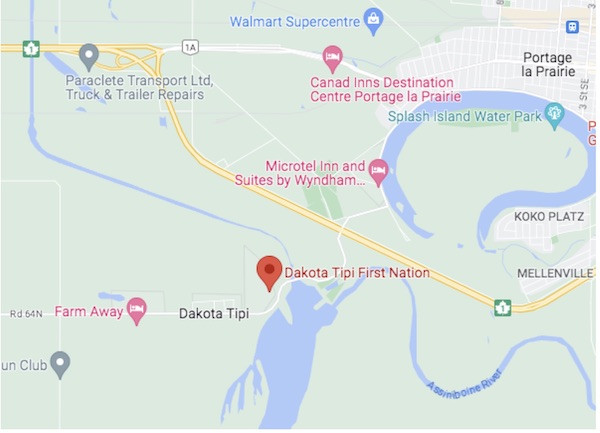

2. Dakota Reservations 3. Dakota-Settler Relations 4. Reserve Farmers 5. The Flee Island Dakota Community Author James Daschuk describes how killing the bison herds led to the devastation of the Indigenous population. Yet, Daschuk wrote, the Dakota Sioux survived the systematic destruction of the bison herd better than other nations. The reason: they were farmers.  Woman working the earth with a scapula hoe. Source: Gilbert Wilson, 1987 (1917). The work of Dr. Mary Malainey, a professor in the Department of Anthropology at Brandon University, has shown us that the history of farming in southwest corner of Manitoba, dates back to the late 1400s. At Gainsborough Creek, her team discovered remains of a tool-making workshop and residential debris — evidence, along with the bison bone hoes, that Indigenous peoples had lived and farmed the area centuries before European contact. Archaeologists don’t yet know who these 1400s farmers were, but we are starting to recognize the extensive knowledge that pre-contact people, including the Dakota, had about horticulture. We also know how the extensive trading relationships in central North America facilitated the sharing of not only the products of farming - but the practices. Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden, written in 1917 by anthropologist Gilbert L. Wilson, recounts the crop production practices of Hidatsa woman Maxidiwiac, also known as Buffalo Bird Woman. She farmed at Like-A-Fishhook village on the Missouri River in North Dakota, 200 kilometres south of the Gainsborough Creek site. Maxidiwiac knew every detail about crop production, harvest and storage. She even knew about pollen drift and selective breeding. Maxidiwiac was not just a farmer, she was an expert farmer. “Corn planted in hills too close together would have small ears and fewer of them,” she told Wilson. Farmers plant corn in wide rows to this day. She also filled the space between corn plants with beans that fix their own nitrogen — an essential nutrient for plant growth — from the air, and with squash that provided ground cover to limit weed growth. Weeds use up moisture and nutrients from the soil, reducing crop yield. Sarah Carter, in her book Lost Harvests, writes about the useful knowledge that First Nations people had: “Their highly specialized empirical knowledge of nature approached a science. They were aware of the vegetation in their environment, and they knew when and how to harvest it. They were much better informed on rainfall and frost patterns, on the availability of water, and on soil varieties than settlers from the East and overseas who were to follow.” That knowledge is displayed today in the work of Dakota Elder Eugene Ross, (profiled elsewhere in this project.). When visited by Agriculture Journalist, Jay Whetter, he demonstrated some of that knowledge. On a short walk from his home he dug up a few tiny plants nestled in the grass. The 15-centimetre plants have thin stems, white flowers and jelly-bean-sized bulbs. “Wild onion,” he said. Ross knows the plants of the Prairies. He knows the history. He recounts that grandmothers, the “keepers of the lodge,” spent all summer and fall gathering food in preparation for winter. “They had their own system that never failed them,” he said. He is now the lodge keeper. Sources: The true history of farming on the Prairies https://thenarwhal.ca/indigenous-prairies-farming-history/ Jay Whetter There are nine Dakota bands in Canada today—four in Saskatchewan and five in Manitoba. Five Dakota reserves were created in Manitoba nations without treaties being involved. Having had the territory supposedly cleared of Indigenous title through the numbered treaties, Canada did not think it necessary to negotiate a new treaty with the Siouan peoples it considered immigrants. But the federal government did think confining them to reserves was the best way to “manage” them.  Chanupa Wakpa Dakota Nation In 1872 the Dakota along the Souris River moved to a proposed reservation just south and west of Grande Clairiere. This temporary 36 square mile reserve was only in use for a short time until a permanent reserve was set up. In 1877 the Santee Sioux, in the Turtles, request a reserve from the Manitoba Lieutenant-Governor. This was granted them on their promise not to aid the American Sioux, who were still at war with the American authorities, and in 1878 they received a reserve north of Pipestone near Oak Lake. Today this is called the Canupawakpa Dakota Nation In 1908 the Reserve included Waphetons, Santee, a few Hunkpapas and some descendents of Chief Inkpaduta (Santess outlawed before 1862 by the main Santee Nation). The first reserve was one square mile in size and was situated on the southwest side of Oak Lake. The Dakota people involved were dissatisfied and suggested a new location. The Chief at this time was He-Ohde. An agreement to re-locate was reached in 1877 and the reserve was relocated to its present site. Sioux Valley Dakota Nation Wipazoka Wakpa SVDN, formerly called the Oak River Reserve, is located in the Assiniboine River valley, south of Griswold, in Southwestern Manitoba. The Reserve was created in 1876. Sioux Valley Dakota Nation is the largest Dakota Nation in Canada with a membership of approximately 2500. Mah’ plya hdes’ ka  Originally a fairly large surveyed area was planned, before the actual reserve was located.  Manitoba Free Press, Jan. 20, 1874  Manitoba Free Press Jan. 20, 1877 On July 1, 2014, SVDN achieved the status of self-government with recognized jurisdiction by both Canada and Manitoba in over 50 areas, creating a true Nation-to-Nation and Government-to-Government relationship between SVDN, Canada, and Manitoba. The self-government negotiation process took over 20 years to achieve. SVDN continues to lead and progress by becoming the only self-governing Dakota Nation in Canada recognized by both the Federal and Provincial governments, and the only self-governing First Nation in the Prairie Provinces. Birdtail Sioux Dakhóta Oyáte (Dakota Nation) (Chankaga Otina) Birdtail Sioux Dakota Nation is lcated approximately 50 km north of Virden, Manitoba and has a population of about 500 people on approximately 7,128 acres (28.85 km2) of land.  Manitoba Free Press - Sept. 6, 1879 From a dispatch cited as: Little Saskatchewan Wanderer. Long Plain (Mah’ plya hdes’ ka) A signatory to Treaty 1, 1871 (Adhesion Treaty of June 20, 1876) Long Plain First Nation is an Ojibway and Dakota community in the central plains region of Manitoba. The Long Plain population is over 4,500 and is comprised of 3 reserves of which 2 are urban. The urban reserves are situated along the city limits of Portage la Prairie and in the City of Winnipeg.  Dakota Tipi In 1972, the Sioux Village Settlement near Portage la Prairie divided the two, therefore creating two First Nations presently known as Dakota Tipi First Nation (IR No #56) and Dakota Plains First Nation which borders the Long Plain First Nation reserve. The Dakota Tipi First Nation was granted reserve status in 1972, and was located on approximately 25 acres. Over the years, the First Nation has increased its land base by a further 346.8 acres, for a total of 371.8 acres.  Other Reserves Saskatchewan, there are three Dakota reserves: the Wahpeton reserve near Prince Albert, the Whitecap reserve near Saskatoon, and the Standing Buffalo reserve near Fort Qu’Appelle. There is also one Lakota reserve in Saskatchewan located at Wood Mountain, which was established by followers of Lakota chief, Sitting Bull, who crossed the border in order to avoid American authorities who were seeking to punish them for their involvement in the Battle of Little Big Horn in Montana in 1876. Sitting Bull eventually returned to the United States in 1881; however many of his followers stayed behind at Wood Mountain and established the reserve community that still exists today. Standing Buffalo led his followers back into Montana Territory, where he was killed in battle on June 5, 1871. His son, taking his father’s name, led part of this group back into Canada, eventually settling on the Standing Buffalo reserve in 1878. White Cap had led followers into Manitoba and eventually into what became Saskatchewan, but when forced by the Métis to join in the fighting in 1885, White Cap’s group was punished; however, once rehabilitated they were given a reserve at Moose Woods. A group led by Hupa Yakta, previously affiliated with White Cap in 1890, asked for a reserve at Round Plain, which came to be called Wahpeton. Most of the followers of Sitting Bull went south and preceded his surrender to US authorities on July 19, 1881; however, a small group of Lakota remained and struggled for survival at the edges of Moose Jaw, and were finally granted a reserve at Wood Mountain in 1910. Some Thoughts on the Nature of Reserves In an Interview, Sioux Valley Elder Oswald McKay offered this interesting perspective. "My mother was in Portage Residential School when she was turning six, or six already, until the age of 16, even though her parents and grandparents were at the village there, two miles to the west. Just a couple of weeks ago, I went to a funeral in Dakota Tipi. It was a traditional man that passed away, a traditional funeral. What he said at that time really hit me. He said “imagine a community with no children.” That’s what these communities went through. Imagine the towns of Napinka, Melita, imagine that today with no children. So that not only changes the children, it changes the adults. That is.. again when you don’t live through something, you don’t think of things He went on…to describe what it felt like to live on a Reserve…. Can’t do that. Not permitted. You could have been sent to jail for that, punished for that. Just imagine that. Imagine the change in lifestyle Loss of freedom from buffalo hunting to being locked in the reserve. Got to have that ticket to move. Who are you doing it with, what’s the purpose of your travel. Just makes you think of a jail cell." That’s interesting because ,,, it was about power. It was important for the government for every kid not to go home. It was all about power; well-meaning people did things, but they didn’t see the big picture. There’s control for political reasons and there’s control for the sake of control. On Feb. 3, 1896 the Daily Free Press reported on a request to form a committee to review requests from settlers for the removal of Dakota people to their reserves. The allegations were somewhat unspecific, just that Dakota were “a nuisance to the settlers…” and that there was “plundering”. The debate brought out some interesting points. While Hon. Mr. McKay asserted that the provisions made for the Dakota were generous and fair, he also noted that: “It was said that these Sioux Indians had become a nuisance and were plundering; but the statement was, to say the least of it, doubtful. Red Indians had very often to bear the blame of outrages committed by white Indians.” Hon. Mr. Gunn pointed out that, “A great deal of the thieving ascribed to the Indians had, no doubt, been the work of white men.” In fact one Indian Agent commented in 1882 that any trouble that had arisen way caused by white settlers who did not like to see Indians in desirable locations. The discussion is interesting and important. Despite the fact most of the people responsible for Government policy and practice regarding “Indian Issues”, were committed to the policy of restricting Indian to reserves, and to various Euro-centric views in general, they also recognized and repeated the fact that settler complaints could be self serving. What a reading of Local Histories from across southern Manitoba tells us is that relation between settlers and local Aboriginal people (predominately Dakota) were amicable and mutually beneficial in the early days. One argument for allowing Dakota “refugees” from Minnesota to remain in Canada was that they were a helpful labour supply for farmers. There was often a mutually agreeable trade established, such as wild game in exchange for consumer goods. The accounts in Local Histories match those memories passed down by Dakota Elders and others coincide with the anecdotal reports passed down through generations. An Important Service Aside from providing casual labour, especially in harvest season, for a limited time there was another very valuable service supplied by Dakota people. Steamboats on the Assiniboine River provided a vital transportation service to newcomers in the period from 1878 to 1885. They required a ready supply of firewood to operate and the route was mainly through territory as yet sparsely populated. Several industrious Dakota men provided that service. Mr. McKay outlines one particular story… … he’d make some cash some money selling wood to the steamboat. Once the steamboat leaves, he’d run to the next stop. So what he’d do is, he cut wood to sell when a boat got to Sioux Valle. It would be going to Fort Ellice so he’s head there, cut more wood there. That’s maybe 70 miles across and he’ll run it, that’s a long ways and he’ll get there before the steamboat got there. (It is true that travel by foot was often faster. To see why, take a look a map of the twisting Assiniboine and consider how slow that journey could be, especially going upstream. Steamboats were never swift, but they carried a lot of freight.)  Free Press June 24, 1876. The report displayed above is typical of many such reports in the 1870’s - 1890’s. Another report tells us that,” Apart from the ill, the aged, and those just beginning to farm, the Oak River Dakota had received no assistance by 1882.They were reported to be well clothed and adequately housed, although an absence of suitable timber continued to be a problem. “The Dakota constructed a large round house on the reserve where they met for dances. The women of Oak River did bead work, knitted, tanned hides and manufactured rush mats and baskets. It was reported that the Dakota got along well with their white neighbours. They were invited to participate in local agricultural fairs where they paraded in traditional dress to the annoyance of Department officials. The Agent commented in 1882 that any trouble that had arisen way caused by white settlers who did not like to see Indians in desirable locations.” (Carter)  Manitoba Free Press - March 6, 1878 These reports, of course, reflected the hopes of both government officials and white settlers. They hoped that the “Indian Policy” would be successful, that there would be no trouble, that somehow the transition from being the real “settlers” of this land to being wards of the white state, would pass smoothly. It was, perhaps, wishful thinking tinged with more than a bit of guilt. Still, it seemed to be working, mainly because the Dakota, along with the other First Nations, recognized that they didn’t have much choice. But, time after time, the story changed. Experiments in reserve agriculture that had started out so promising, began to falter. The stories are well documented and once again they match the stories passed down through the generations. Rules, restrictions, the pass system and interference by the Indian Agents all played a part in derailing what started our so well. An Elder phrased it this way: “It’s total control of Indian life, you know. Total control. You’re under the watchful eye of the agent. “ At the root of it was the policy direction provided by Commissioner Hayter Reed. Instead of encouraging the progress in farming, the Dakota were discouraged. The policy of the Department was to encourage subsistence level farming among Indians, in which they produced for their own needs and not for the market. Commissioner Reed instructed Indian Agents in western Canada that the manner best calculated to render Indians self-supporting was to emulate “peasants” of other countries who kept their operations small and their implements rudimentary. In what was essentially a social engineering project, Reed thought that the Indian farmers would benefit from avoiding labour saving machinery and suggested that, “this is commonly accomplished by peasants of various countries with no better implements than the hoe, the rake, cradle, sickle and flail. The necessary use of these implements can never be acquired if Indians contemplate the performance of their work by labour-saving machinery. The Department’s goal was: “... to restrict the area cultivated by each Indian to within such limits as will enable him to carry on his operations by the application of his own personal labour and the employment of such simple implements as he would likely to be able to command if entirely thrown upon his own resources, rather than to encourage farming on a scale to necessitate the employment of expensive labour-saving machinery. “ While Reed actually may have believed some of this nonsense, it seems no coincidence that this approach prevented the Reserve farmers from competing with their white neighbours. What happened was, that farmers on the reserves couldn’t succeed under these conditions and many found it better to rent out the land to neighbouring settlers and work for them…to find other ways to survive, A Dakota Elder tells this story…. “After the incident in ‘62, of course some of them got instruction on how to farm. They were really successful. Then they put in all these quota systems, you can’t do this you can’t do that. One of the farmers in the Portage area, he goes to an Indian agent and he asks, “Can I sell some of my cattle or I want to sell some of my crops, because I want to go visit my son, he’s in Portage residential school. He was denied permission. So that farmer, he got so frustrated. No incentive. So he went home and he opened the gates and he shooed his cows out and said. “I’m going to sit back and be an Indian.” It must have been frustrating to be told that the European capitalist, private ownership view of the world was the goal, that their way of like was not only wrong, but almost immoral and primitive. To be told that if you’re going to deal with their society you’ve got to understand private ownership and overturn centuries of culture. Then when the sincere and successful efforts are made to conform to what they accepted as the new reality, to be shut out. The Dakota, and others, were criticized and blamed for not aspiring to that lifestyle, and then, when they tried to succeed in the white man’s world, they were denied a chance to compete. Sources: Sarah Carter Seeding Resiliency: Dakota Farming in Canada Written by Hañwakañ Blaikie Whitecloud. Not only are Dakota people not bound by Treaties, some successfully resisted being placed on reserves. Some of the Dakota who lived on the Portage Plain remained in this area after reserves were established, hunting, fishing, trapping and working as labourers for local farmers. In 1893 however, sponsored by local residents, 21 Dakota purchased River Lot 99 at the eastern end of the Portage la Prairie settlement. Several years later, Lot 14 was added to their holdings. However, encouraged by government officials, many families had moved to lands adjacent to the Ojibwa Long Plain Reserve (Long Plain Sioux Reserve) by the mid 1930s. Some Dakota remained on Lot 99 until the late 1950s, when new lands were acquired for them on River Lot 25. This new location became the Dakota Tipi Reserve. “Flee Island” locale was home to as many as twelve Dakota families as late as 1920. Some of their descendants still live in this part of the province today. https://www.usdakotawar.org/stories/communities/dakota-tipi-first-nation |