|

|

|

Part 1: Who Are the Dakota? What is their history in Canada? How did the relationship between them and Canada evolve? 1. Dakota Origins 2. The British Connection 3. The Arrowsmith Map 4. The Dakota Claim 5. Border People 6. The Minnesota Uprising 7. The “Sioux Wars.” 1. Dakota Origins The Turtle

Mountain area is the oldest human habitation in what is now

Manitoba. Here, courtesy of Canupawapka (Pipestone) elder Frank Brown,

is the Dakota creation myth. Myths, like the more familiar Greek and

Norse tales, are allegories -- pre-history masked in the form of a

story, often a fantastic one.

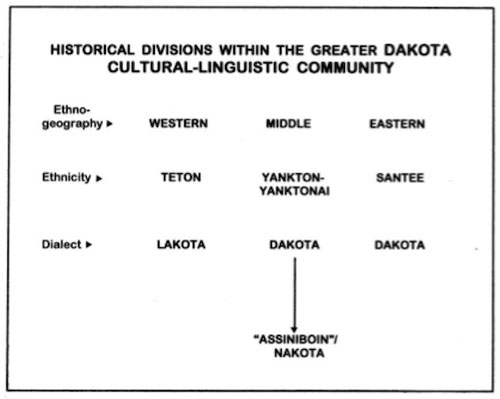

"I'll go back to the beginning of time, before the Ice Age. The Creator gave us a choice, whether we wanted to remain in spirit form in the earth. Or do we want to be human beings. Some of us agreed to become human beings. The others remained in the earth... You don't see them.... "When we agreed to be human, God gave us a territory and a language and with the territory and the language, he gave us an animal, to provide us with food, with clothing, with tools and even a home. That home we see today is the teepee. "When God said, "Your territory is where the buffalo roams," that's the natural law." Historian, David Reed Miller suggests, “The ancestral Dakota were associated with mid-western Woodland archaeological complexes concentrated at the Mississippi River headwaters in the parkland transitions zones between forest and prairie. Linguistically part of the Siouan language family, dialects emerged to distinguish the Dakota proper (Mdewakanton, Wahpeton, Sisseton, and Wapakute) and middle division (Yanktonai and Yankton) from the western division Lakota (Teton).  The Dakota

expanded onto the eastern prairies in the mid-17th century

after access to French trade goods, including firearms increased their

population. In the early 18th century, Ojibwa-Dakota conflict over

hunting territories and access to traders in the Mississippi watershed,

prompted the Lakotas to move west onto the prairies. As horses came

through the trade networks, Lakotas expanded in number and expanded

into neighbouring regions that comprised the border regions and

territories of their enemies: Lake of the Woods and Rainy Lake, Turtle

Mountains/Pembina Hills, as well as the Souris and Missouri-Yellowstone

Rivers regions.

The Dakota became allies of the British and were increasingly bound to them by treaties and trade alliances, involving fighting as British allies in the War of 1812. The arrival of the Americans to the upper Mississippi in1805, caused the Dakota much concern. While the French had been acculturated as kinsmen, when the Americans arrived, they did not grasp the importance of reciprocity for the Dakota. The American appetite for land and resources was never satiated. By the 1850s the Dakota were left with reservations upon which they were allowed to reside only at the discretion of the President of the United States. This dependency left them vulnerable and periodically destitute. The events of the early 1800’s set the stage for the conflicts with settlers and the US Army that dominated the second half of that century. There are

people in Dakota Communities that have Medals from the War of

1812-14, passed down from their great-grandfathers and beyond.

1814 Chief’s Medal Service as British allies in the War of 1812 remains an important part of the Dakota history. Though the ancient history attesting to the presence of Dakota in Canada forms the basis of the Dakota’s claim to more land, they also argue that the Canadian government has an obligation to them due to their military help during the War of 1812. Military alliances between the British and Dakota go back to the 1760s when Britain took over full occupation of Canada and the North-West Territories. At this time the Dakota established a friendly relationship with the British; one of peace, economy, trade, and military alliance. They pledged that they would have nothing to do with the Americans and would defend the English king in return for promises of everlasting obligation from the British Crown. This pledge was honoured in the following decades of unrest. Even when the Americans pushed the British out of what became the United States at the end of the American Revolution of 1776, the Dakota refused to shift their allegiance over to the Americans. Thus, in 1812 when the British engaged in another military struggle against the Americans the Dakota were still willing to fight for British interests.  Upholding this military alliance had a strong negative effect on the Dakota. Not only did they suffer loss of life in the 1812 conflict, they didn't have time so late in the season to stock up enough food to last them through the winter. As a result, many Dakota starved to death. Nevertheless, the Dakota stood ready to defend their lands and those of the British, as agreed. During the conflict there was nothing but praise from the British for their Dakota allies and reiterations that their interests would be staunchly safeguarded when the fighting subsided. The War of 1812 ended in 1814 when the Treaty of Ghent was signed by Britain and the United States. However, with its signing the Dakota were betrayed by the British who reneged on their promises and abandoned them to eke out what agreements they could with the American government. In 1818, under the Treaty of Ghent, the assurances they were given, that their land right would be respected were not respected, and the US was given Dakota land. Even so, the US Government also gave the usual assurances, and as they had done for two centuries, kept ignoring their own treaties. The Dakotas really believed in the Great White Mother as they called Queen Victoria. Years later their relatives would seek help from the British and show these medals to the Manitoba authorities. Years later when a group of Dakota brought a captured American cannon to Fort Garry. the British authorities at the fort named the cannon “Little Dakota” and promised to aid them whenever they were in trouble. 3. The Arrowsmith Map In 1880,

Peter Fidler, was sent to the confluence of the Red Deer and

South Saskatchewan Rivers, in the heart of Blackfoot territory, to open

Chesterfield House. There he met Blackfoot Chief Ackomokki, who had

approved of the opening of the trading post. Ackomokki was known to fur

traders as "Feathers" (or "Painted Feathers").

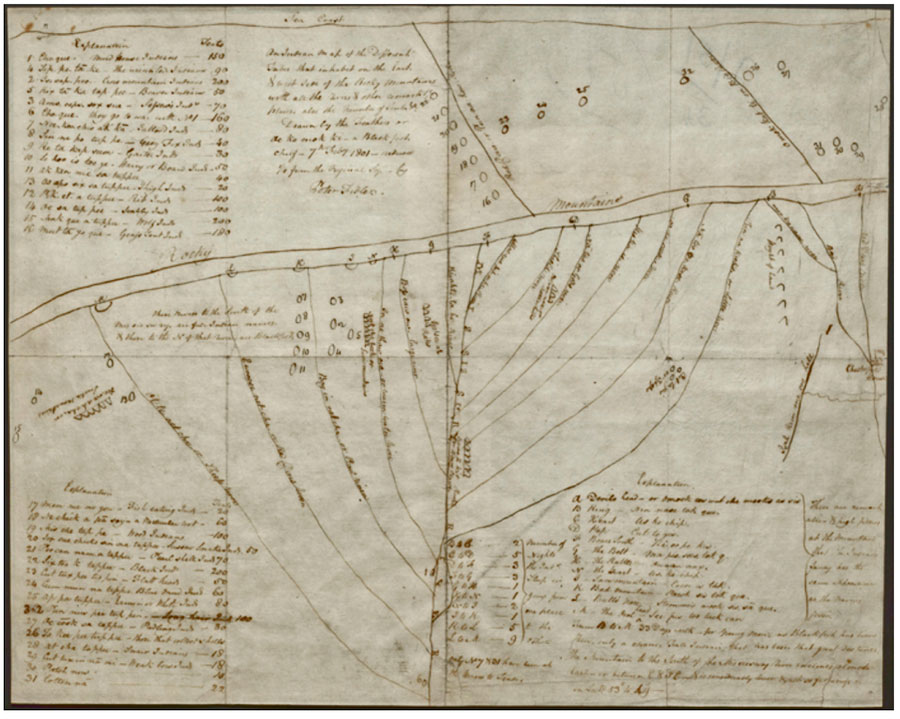

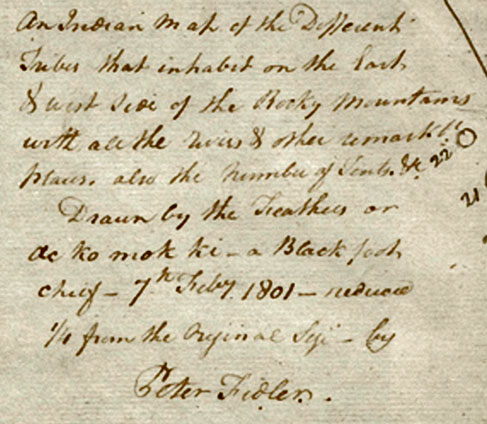

Some time in 1801, Ackomokki, met with Fidler and drew him a detailed map of the lands around the Upper Missouri, including names of rivers, mountains, and travel time between them, naming 32 Indigenous communities populating the region. Fidler, a renown map-makers, explorer, surveyor, and manager would have recognized the value of the information. He carefully copied that map and gathered what he could from the knowledge extensive knowledge the Chief was willing to share.  The writing

along the left side names the “Indian” settlements

identified by Ackomokki with the names used locally at that time. Names

such as: “The Mud House Indians”, “The Tattoed Indians”, “The

Grey Fox Indians”, and “Fish Eating Indians.” The number of tents

is included for each, a common way of estimating populations. The

writing top centre is Fidler’s explanation. (See details below).

The double line running left to right depicts the Rocky Mountains and river in the region. Further information about landmarks, travel times are included in the bottom right corner. Fidler had extensive experience in the west and much knowledge gained by his respectful interactions with the Aboriginal population. (Fidlers wife and life-long partner was Mary (Methwewin) Mackagonne, a Cree woman, and together they had 14 children.) He would have been able to incorporate this information into his own map-making and record keeping.  “An Indian Map of the Different Tribes that inhabit on the south and west side of the Rocky Mountains with all the rivers & other remarkable places, also the Number of Tents Etc. Drawn by …. AcKoMokKi, a Blackfoot Chief 7th (July) 1801. ¼ from the original size by Peter Fidler” John

Arrowsmith a well-known British mapmaker is credited with many

important maps of North America (and elsewhere). He never came to North

America, so relied on previous maps, on information from the British

military and on the Hudson's Bay Co. and fur traders such as Filder. He

began publishing maps of of the northern plains in the early 1880, and

continued revision and updates until 1857.

Ackomokki’s drawings were later incorporated into the 1802 edition of Arrowsmith's map of the Interior Parts of North America.  An excerpt from Arrowsmith’s 1857 edition. Since the

mid 1800’s the Canadian government has insisted that Dakota

Nations have no claim to land in Canada, because they only arrived in

Canada after battles won and lost with the US cavalry in the 1860s and

70s. But the Arrowsmith Map clearly shows the Dakota as a primary

Indigenous Nation of the central Prairies in the early to mid 1800s.

Their territory reached from what you call Iowa in the south, to north

of today's Calgary.

To the three Dakota communities in Southwest Manitoba the map is another piece of evidence in their ongoing a quarrel with the government of Canada regarding their rights. One interesting thing about the map is how it corroborates the oral history that has been handed down by the Dakota themselves. Oswald McKay, an elder from Sioux Valley recalls that he like many other learned from his grandmother that this was Dakota Territory here. He suggests that the map shows there were likely more Dakotas north of the 49th parallel than there were on the southern side. “‘Tell me, good Weyuha, a legend of your father’s country,’ I said to him one evening, for I knew the country which is now known as North Dakota and Southern Manitoba was their ancient hunting ground.” Charles Eastman, Wahpeton (Santee) Dakota, 1902 While the

Governments of Canada, from the mid 1800’s up to the present,

have always insisted that the Dakota were “American”, there is ample

evidence of their presence in Canada over centuries.

Archaeological evidence, fur trade documents and diaries, as well as oral tradition all point to the continued and notable presence of Dakota people in Canada. Early Dakota left behind fragments of pottery in Canada, which date back 800 years. These fragments indicate part of the territory occupied by Dakota long before the contact era. Historical accounts support the conclusion that the Dakota once occupied land in Canada. The earliest European records that are available date back to the 1700s when fur traders came into contact with North America’s indigenous peoples for the first time. Hudson’s Bay Company records indicate that the Dakota were active in Canada as far north as Churchill River in northern Saskatchewan. A group of Cree living in this area called their village Kimosopuatinak, meaning “Home of the Ancient Dakota,” which confirms a strong Dakota presence here. From every decade between 1760 and 1860, at least one document (letters, sketches, etc.) or an eyewitness account was found to attest to a Dakota presence in Canada. Meetings between these recorders of history and the Dakota occurred sometimes 100 years before the Dominion Government acquired the territory that today makes up Canada. It is interesting to note that the Assiniboine (Nakota) who are accepted as “Canadian” have common roots with the Dakota. The Dakota split from the Nakota some centuries ago. The people we know as “Assiniboins” trace their origins back to the Central Siouans. From Central Siouan evolved Proto-Dakota and then Dakota, the immediate ancestor of the “Assiniboine”/Nakota”. The government officials who originated the argument that the Dakota are from “somewhere else” in fact may simply have been following the colonial practice of ignoring aboriginal history. Sources: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/dakota CANADIAN DAKOTAS Leo Pettipas Manitoba Archaeological Society 5. Border People Historian

David McGrady offers another look at the question, “Who are the Dakota?”

His thesis, “Living With Strangers: The Nineteenth Century Sioux and the Canadian - American Borderlands”, considers Dakota History as the story of a borderlands people. Their situation along this political dividing line gave rise to both conflict and cooperation. At times they used this to their advantage. He looks at how that shaped who they are today. “When Sitting Bull and other Lakota leaders took their followers north to Canada following the Great Sioux War of 1876/77, their pathway was already in place and well travelled. Throughout the history of their interaction with incoming national powers, the Sioux used their position in the borderlands as a tool to improve their lives.” Earlier, the Dakotas from Minnesota used the boundary as a shield against the United States Army after the Dakota Conflict of 1862.” The border also provided complications. They had to deal with two different sets of government policies, two distinct groups of missionaries sent from different eastern cities, and two different experiences with European forms of law enforcement.  Manitoba

Free Press July 22, 1876

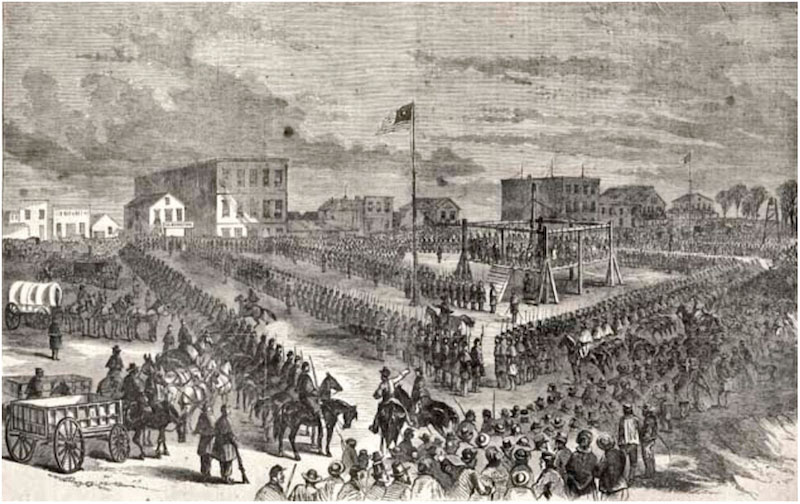

Manitobans watched events south of the border closely In the nineteenth century, Dakota often travelled from their villages on the Minnesota River to the Red River Settlement in Rupert's Land in efforts to preserve their trading relationship with the British. The basis was laid in these years for a their life in the Anglo-American borderlands from Minnesota onto the Plains. The Manitoba newspapers of the time documented influence of the border on the complex relationship between the Dakota and the settler population. 6. The Minnesota Uprising On December 26, 1862, the federal government hanged 38 members of the Dakota tribes in Minnesota. It was the largest mass execution in United States history. This event was noteworthy in several senses.  The execution at Mankato Copied from a sketch by W.H. Childs in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, January 24, 1863, page 285. Courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society The Dakota

were tried, not in a state or federal criminal court, but

before a military commission composed completely of Minnesota settlers.

They were convicted, not for the crime of murder, but for killings

committed in warfare. Many wars took place between Americans and

members of the Indian nations, but in no others did the United States

apply criminal sanctions to punish those defeated in war.

The trials themselves were deficient in many ways, even by military standards; and were not conducted under military law. The trials commenced on 28 September 1862 and were completed on 3 November; some lasted less than 5 minutes. No one explained the proceedings to the defendants, nor were the Dakota represented by defense attorneys. Colonel Henry Sibley ordered the creation of a military commission to conduct the trials. One year later, the judge advocate general determined that Sibley did not have the authority to convene such trials due to his level of prejudice, and that his actions had violated Article 65 of the United States Articles of War. However, by then the executions had already occurred. The treatment of defeated Indian rebels against the United States stood in sharp contrast to his treatment of Confederate rebels. President Lincoln, ultimately responsible, never ordered the executions of any Confederate officials or generals after the Civil War. These unprecedented executions were in response to public pressure, not the needs of justice. Even the staging of the event as a public spectacle was a carefully orchestrated political act. They built a special scaffold to hang them all at once & made Dakota women, children & elders watch as the crowd cheered. Most historians now believe that many of those executed were innocent of the crimes of which they were accused. How did this come about? As happened with all the Aboriginal Nations, the Dakota were pushed ever westward as treaties we made and then broken. They participated in the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty that began a process of fixing the boundaries of tribal territorial domains, with pledges of annuities for cessation of intertribal warfare. Soon promises made were all but forgotten amidst the graft and corruption in the Indian service. The United States government and Dakota leaders negotiated the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux in 1851, and the Treaty of Mendota, also in 1851, by which the Dakota ceded large tracts of land in Minnesota Territory to the U.S. in exchange for promises of money and supplies. From that time on, the Dakota were to live on a 20-mile (32 km) wide centered on a 150 mile (240 km) stretch of the upper Minnesota River. However, the U.S. Senate removed Article 3 of each treaty, which set out reservations, during the ratification process. In addition, much of the promised compensation went to traders for debts allegedly incurred by the Dakota, at a time when unscrupulous traders made enormous profits on their trade. Supporters of the original bill said these debts had been exaggerated. The breaking point was reached between August and December of 1862, with the failure of the United States to deliver promised food and supplies. Young men refused to watch their families starve any longer. The Dakota, with Little Crow as a somewhat reluctant leader, responded in an uprising, killing 490 white settlers. The US responded with a comprehensive military effort, arresting as many Dakota as they could. Sources https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/execution-dakota/ The Minnesota Uprising - A Local Connection There is a direct connection between this uprising and the Dakota people in Manitoba. Oswald McKay, from Sioux Valley, who learned the tale from his Grandmother, tells it this way: “These young men, young warriors had been hunting and they were coming back. They were hungry already, starving. All the provisions were in the storehouse but they weren’t given out for whatever reason. They were waiting, waiting, waiting. By that time they were not to hunt out on the land. The settlers were moving in already. Anyways these guys they went to hunt and on the way back, they came upon these settlers. One warrior, he saw that they had some chickens, so they decided to go steal some eggs, but they were discovered while they were stealing eggs by the farmer’s wife. What happened was that, after they were discovered stealing eggs, the farmer’s wife went after the warrior. She might have scolded him or hit him with a broom or something, but they were laughing at this young warrior. They were kind of goading each other, until the young man said, “I’m going to go back.” They went back and they killed that family there. “What are we going to do now?” Because already they wanted to do something because they were starving. They had to do something. That was an opportunity for them to rise against the government. That’s what happened, so my great-great-grandfather living in the community north of there, when they were preparing themselves for the war, they came to the northern part of the area, to ask the warriors there to give them a hand.” Elder McKay makes this observation: “I’m interested in the egg incident. It seems that several incidents that happened and caused major battles were caused by insult, impertinence, the refusal of the white settlers here to take people seriously. Like the Frog Lake and the whole Metis thing and it could have been avoided. The Cree people in Saskatchewan were extremely patient and they knew the realities that they were faced with, this gigantic force from the east. They knew they were powerful. It’s like they goaded them unnecessarily, and some of the bloodshed could have been avoided if people had been just a touch more reasonable. Telling the Truth - A History Lesson In 2012, to mark the conflict's 150th anniversary, Mankato native and former MPR reporter John Biewen produced a documentary about it. Though he grew up in Mankato, he heard next to nothing about the U.S.-Dakota war during his childhood there. So he traveled around southern Minnesota to places where key events occurred, to explore what happened in all its complexity. Biewen also looked at the shifting ways Minnesotans have, or have not, told themselves the story of the Dakota war over the years. The documentary is called "Little War on the Prairie." https://www.mprnews.org/story/2017/06/07/little-war-on-the-prairie-documentary A thought about teaching history…. "We all learn how to teach what we're teaching ... We learn how to teach chemistry. We learn how to teach rocket science. We have to learn how to teach Minnesota Indian history," said Osseo Area school district secondary Indian education director Ramona Kitto Stately. Stately said her great, great grandmother was one of a group of mostly women and children force-marched to a prison camp at Fort Snelling following the end of the U.S.-Dakota War. "I have teachers who ask me, 'When is it appropriate to tell kids this story?'" she said. "My answer is always the same: 'When is it appropriate to lie to them?'" In the 1870’s Western Canadians were very connected to our neighbour to the south. Our “undefended” border was barely a border at all in that there were people coming and going all the time. In west-central US, the conflicts between settlers and First Nations, which by the 1870 had taken the form of full-scale war between the US Cavalry and the Dakota, were very close to home. The Manitoba Free Press reported regularly about the conflicts, and their stories were, of necessity based on US sources and reflected US optimism. These two excerpts from the Manitoba Free Press, May 31,1876 set the stage…  One is reminded that in the early years of the 21st Century the US was pretty sure that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan would be over quickly. Wars seldom go as planned. The conflict created a political and military dilemma for Canada, one that as acutely felt in Manitoba. On the one hand, news reporters seemed to realize that the US had brought some on this upon themselves, but on the other hand they also seemed to buy the US view that civilian casualties were always frames as atrocities or massacres, except when they did it. |