by James B. Hartman

Continuing Education Division, University of Manitoba

|

The story of the establishment of churches in Winnipeg can be traced back to the early days of the nineteenth century. The Scots philanthropist and Hudson’s Bay Company shareholder Thomas Douglas, Fifth Earl of Selkirk, planned to open the newly ceded Hudson’s Bay Company territory to displaced tenant farmers from Scotland and Ireland who had been driven from their homes by their sheep-raising landlords. The first contingent of settlers came to a partially burnt-over promontory within a wide bend of the Red River named “Point Douglas” on 27 October 1812; almost two years later, in June 1814, the arrival of the Kildonan Scots marked the true launching of the Red River Settlement.

This article will provide a brief account of the establishment of the major churches in Winnipeg from the dates of their founding through the early decades of the twentieth century, and sometimes later where appropriate. The criteria for their inclusion are that they developed into fairly large buildings and congregations that exercised significant influence on the religious and social affairs of their immediate communities or the city at large. The roughly chronological treatment includes the relevant historical background, information about church founders, descriptions of the construction and architectural features of church buildings, congregational activities, and related unique anecdotal information, along with notes on organs installed in the churches. On account of its geographical proximity, the City of St. Boniface is considered part of the district of Winnipeg for the purposes of this study.

The issue of churches and religious leaders was a matter of concern for the Selkirk settlers for they regarded this lack as a mark of an uncivilized society. For this reason, the colony’s first governor, Miles Macdonell, negotiated with the Roman Catholic Bishop Joseph-Octave Plessis in Montreal to send a missionary to minister to the needs of the settlement’s Irish and Scottish Catholics and other “free Canadians” at Red River. Fathers Joseph Norbert Provencher and Severe Dumoulin, along with the seminarian Guillaume Edge, arrived at Red River in mid-July 1818. Part of their task was to reinforce the authority of the Catholic Church among its local members, to convert the Métis (French-speaking descendants of the voyageurs and aboriginal women), and to establish “a regular mode of life,” specifically tenant farming. The three priests immediately constructed a small building that served as a residence and chapel on the east bank of the Red River near the present site of St. Boniface Cathedral. However, this log structure, the first church building in Manitoba, was later damaged in the disastrous flood of May 1826.

This chapel was succeeded in 1819 by a church (designated a cathedral in 1822) to which Lord Selkirk donated a bell. A series of cathedrals followed: the second, a stone cathedral was commenced in 1833 but not completed until 1837 due to lack of funds; it was destroyed by fire on 14 December 1860. This was the church whose prominent twin towers are celebrated in John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem, The Red River Voyageur:

The bells of the Roman mission,

That call from their turrets twain

To the boatman on the river,

To the hunter on the plain!

The third cathedral, commissioned by Bishop Alexandre Tache in 1862, was demolished in 1909; the fourth, the largest of all, built between 1906 and 1908, was destroyed by fire on 22 July 1968. Construction of the fifth cathedral, a low building of contemporary design placed within the remaining walls of the fourth St. Boniface Cathedral, was commenced on 30 June 1971; it was dedicated on 17 July 1972.

The first reed organ (melodeon) in Manitoba was built by a military medical officer for the second cathedral; it was destroyed in the 1868 fire. The first pipe organ in Manitoba was installed in the third cathedral in June 1875. Louis Mitchell, the builder, accompanied the instrument overland from his Montreal factory through the United States and down the Red River by steamboat. The organ–probably a 12-rank instrument—was the gift of a group of friends of Bishop Alexandre Tache in recognition of the thirtieth anniversary of his departure from Quebec for the mission at Red River, and of the twenty-fifth anniversary of his appointment as archbishop of the diocese. The organ was the focus of attention at its inauguration during a “Grand Concert” on St. Jean Baptist Day on 24 June 1875. Subsequent organs included a two-manual instrument by Casavant Freres, St. Hyacinthe, Quebec, purchased from the First Lutheran Church, Winnipeg, in 1921, and a large three-manual, 47-stop instrument, also by Casavant, in 1955, which was destroyed in the 1968 fire.

The “turrets twain” of St. Boniface Cathedral, 1858.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

St. John’s Cathedral stands upon historic ground, the site where Lord Selkirk first met his settlers in midsummer 1817. Through the combined efforts of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Church Missionary Society of England, the first Anglican minister, Rev. John West, formerly of a parish in Dorsetshire, England, arrived at Red River on 14 October 1820. He was the first Protestant clergyman in Rupert’s Land. His intention was to put up a “substantial building” that would serve as a schoolroom, dormitory, and church; a simple wooden structure was put up in 1822. This log building barely survived the great flood of 1826.

When John West returned to England in 1823, his successor, Rev. David Jones, a young Welshman, assumed West’s duties. He laid out the foundation for a new “Upper Church,” a stone structure that was officially opened on 26 November 1833. The Red River Academy, a boarding school for the children of the officers of the Hudson’s Bay Company and for the training of native missionaries, was also established. The church was consecrated as the first cathedral in Rupert’s Land in 1853.

Although other clerics—William Cockran, John Macallum—served briefly in the community, the Right Reverend David Anderson, appointed the first bishop of Rupert’s Land in 1849, was a major force in the parish of St. John’s, including promoting the construction of a new church. Nine years after the great flood of 1852 had damaged buildings on the site, the existing church building was torn down in 1861, and the cornerstone for the second cathedral was laid in June 1862. Stone from the 1833 structure was used in the new building. Bishop Anderson left Red River in May 1864, after he had ordained twenty candidates for Holy Orders, including four Cree Indians and four half-breed youths.

The building of a new cathedral was the dream of Anderson’s successor, Archbishop Robert Machray, and a plan was put forward in 1911 by Archbishop Samuel Matheson for a building that would be completed in time to mark the centenary celebration of Rev. West’s arrival at St. John’s. After some delays, the demolition of the second cathedral began in March 1926, and the cornerstone for a new church was laid on 6 June. Much of the stone from the old cathedral, including materials from the 1833 building, were used. Two of the stonemasons, by now in their eighties, had also worked on the 1862 building. Nearly 200 people attended the first service in the cathedral on the Sunday morning of 5 December 1926.

The present building incorporates elements of medieval English design, with a Norman tower and barrel-vaulted ceiling, and Gothic arched doors and windows. The cathedral contains many mementos and memorial tablets relating to the history of the Anglican Church at Red River. In addition to the large Great West Window of stained glass that commemorates earlier church leaders, other windows depict various historical and ecclesiastical events.

The cathedral cemetery, which contains the burial places of Selkirk settlers as early as 1812 (the oldest marked grave is 1817), is a history of Winnipeg in stone.

It can be assumed that music in the 1862 cathedral was provided by reed organs until an organ committee was appointed in 1900. A two-manual, 14-stop Compensating Pipe Organ (hybrid reeds/pipes) replaced a smaller model in 1902. This was succeeded by a two-manual, 19-stop Casavant instrument in 1927, revised to three manuals, 39 stops, through the 1950s until 1980; this instrument serves the church’s musical needs today.

For more than a generation there was no Presbyterian minister at Red River although the residents had petitioned the Hudson’s Bay Company to provide one. Nevertheless, the arrival in 1819 of the Anglican minister Rev. John West accommodated the spiritual needs of a large number of Scottish Presbyterians who reluctantly attended his services. Eventually the Presbyterian Church of Canada selected a missionary for the Red River colony, Rev. John Black. Black had just been ordained at Knox Church in Toronto on 31 July 1851, the day before he began the long and arduous journey by stagecoach and birchbark canoe to the distant Red River Settlement. He reached Kildonan on 19 September 1851 and held his first service about a week later in the partially completed building that his people had put up; about 300 original settlers and their descendants attended. Their only disappointment was that Black, a Lowlander, did not speak their beloved Gaelic, a difficulty that was soon overcome.

In the winter of 1851-2 the congregation began the construction of a more substantial building, modelled after the Kildonan Church in the town of Helmsdale in Sutherlandshire, Scotland, from which many of the settlers had come. The workers hauled limestone across the prairie from Stony Mountain 23 kilometres distant, and they used trees felled by hand at St. Peters to the north of the parish and from the present Bird’s Hill area. A major setback was the Red River flood in the spring of 1852 that washed away much of the essential materials and damaged many homes. Many people sought refuge in the Stony Mountain area where the minister held services.

The settlers resumed work on the church building for which the cornerstone was laid on 11 August 1852. The stonework was directed by Duncan McRae, the Hudson’s Bay Company mason who was also responsible for other architectural landmarks in the area, such as St. Andrew’s Church and sections of the walls at lower Fort Garry.

The church opened on 5 January 1854; it had a seating capacity of 510 and cost 0,500. Writing to a friend, Black proudly reported: “The walls stand firm and plumb, no leaning, no cracks, and we all begin to be proud of our Kirk as a substantial, commodious church, and withal, especially within, a handsome edifice.” The church, along with the adjacent manse and schoolhouse, was the centre of the religious, social, arid educational life of the community—education, in particular, was considered to be an essential counterpart to religion. The first Manitoba College building was erected on the site in 1872, after classes had been held in the pioneers’ home for several years.

Consistent with Presbyterian tradition, the interior of the church was simple and without display, and the placement of the pews focussed on the central pulpit; several pews were reserved for leading members of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the governor, and other prominent people. Two Carron iron stoves, imported from Scotland, provided heating. Among later alterations were four stained glass windows deeply set into the stone walls, and three exquisitely crafted chancel chairs, fine examples of High Victorian ecclesiastical furniture.

Music in church was not readily accepted by the Presbyterians, for in that denomination throughout the country neither organs nor hymns were allowed; the only singing was metrical psalms, sometimes supported by a bass viol or flute. This situation continued until 1872, when the General Assembly decided to permit the use of organs, formerly described as “carnal instruments.” In a debate on the question at Kildonan, an older gentleman announced that if an organ were put in the church, he would bring around Old Bob, his horse, and take the “kist o’ whustles” out of the house of the Lord and dump it by the roadside. When a reed organ eventually was installed, another disapproving member transferred to nearby St. Andrew’s mission church, unaware that a small melodeon was used in services there, too. But soon after his daughter was appointed to play the instrument in Kildonan Church he returned there. This repentant parishioner was John “Scotchman” Sutherland, later an elected member of the first Legislative Assembly of Manitoba.

The weathered tombstones in the cemetery, which include many of the original Selkirk settlers, stand as mute testimony to a significant aspect of the area’s vigorous early history.

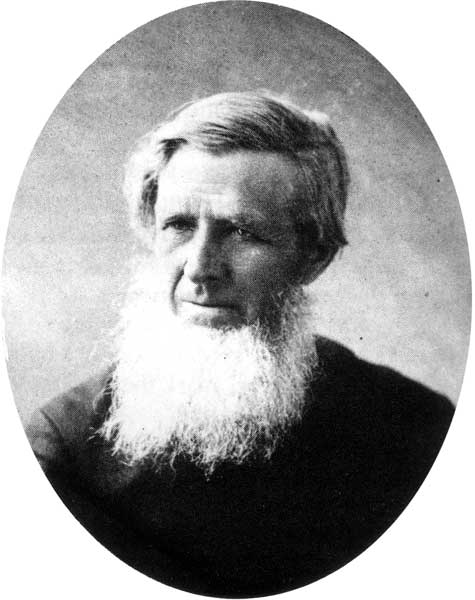

Rev. John Black, circa 1880. Black, who arrived in Red River in 1851, was the first pastor of Kildonan Presbyterian Church.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

The western development of the Red River Settlement along the Assiniboine River took place gradually in the 1830s and 1840s with the arrival of military pensioners, retired Hudson’s Bay Company personnel, and farmers from other established parishes. By 1850 the occupation of river lots along the north bank of the river stretched for several miles from upper Fort Garry, well out of reach of its religious centres. Accordingly, Bishop David Anderson of the newly created Diocese of Rupert’s Land decided to organize a church and school in the district under the auspices of the Church of England. In October 1850 he appointed Rev. W. H. Taylor to undertake this task. In 1851 a site was selected on high ground at the location of an old Indian burial ground that was believed never to have been covered by water in times of flood. Ironically, however, although the flood of 1852 that carried away the first timbers of the church interrupted construction, the rectory that had already been built served as a place of refuge for many residents living nearby.

After the floodwaters had subsided, the required oak timbers were floated down the river from Baie St. Paul, hewn by hand, and fitted into place by the men of the parish. The church was completed following the cornerstone ceremony on 8 June 1853 and was consecrated on 29 May 1855. The total cost of the building in material and labour was £323.15s.1d. In a report to the Society for the Propagation of the Christian Gospel, Rev. Taylor described the architectural features of his new church in some detail, stating, “The whole will, it is hoped, have a decent and becoming effect. It is quite a new thing in this country. … We make no pretence to ecclesiastical correctness—and no doubt have and shall fail on many points—but we have done our best in this case.” The church, designed in the spirit of the Gothic Revival, had a tower on the west end, but it was removed in 1871 because the foundations could not support its weight. It was believed that the old church tower was used as a lookout in the Riel Rebellion in 1869. This precious landmark is the oldest standing wooden church in Manitoba and one of the oldest ecclesiastical structures in Winnipeg.

Methodism was introduced to western Canada with the arrival on 4 July 1868 of Rev. Dr. George Young in Winnipeg where he planned to found a mission. In his book, Manitoba Memories (1897), he recalled the state of the city on that day: “What a mass of soft, black, slippery and sticky Red River mud was everywhere spread out before us! Streets with neither sidewalks nor crossings, with now and again a good sized pit of mire for the traveller to avoid or flounder through as best he could: a few small stores with poor goods and high prices ... neither church nor school in sight or prospect; population about one hundred—such was Winnipeg on July 4th, 1868.”

Despite many difficulties Dr. Young was optimistic about the ultimate outcome of his task, and for a few months he held services in a small building on the corner of Notre Dame and Victoria Streets, and also in a log building to the northwest of old Fort Garry.

The predecessor of Grace Church was Wesley Hall, a building at the corner of Main Street and Portage Avenue that Dr. Young occupied on 13 December 1868; upstairs rooms were used as a parsonage, and the lower space was used as a church and Sunday School room. Early in 1869 the Hudson’s Bay Company presented the congregation with an acre of land at the southeast corner of Water and Main Streets, where construction was commenced on the second Wesley Hall, which was opened on 17 August 1869.

The increase in local population and the expansion of the church’s work soon dictated the need for a more commodious building. Although plans for its erection were delayed by a grasshopper plague and by the first Riel Rebellion, the structure—by now known as Grace Church—opened for worship on 17 September 1871. In the following years the congregation relocated first to an old skating rink, then to spacious rooms over a new block of stores that became the third Wesley Hall. They remained there until a new American-style brick building with Victorian architectural features was erected at the corner of Ellice and Notre Dame Avenues; the church’s first leader, Dr. George Young, dedicated it on 30 September 1883. Although Grace Church was regarded as the mother church of Methodism in western Canada, the wealthy congregation of the downtown church drifted away into the new city suburbs over the years, and the church building was demolished in 1955 to make way for a parking lot.

A reed organ was acquired in 1873, and the church’s plan to have a large pipe organ was fulfilled when a three-manual, 34-stop instrument was installed by R. S. Williams & Son, Toronto, in December 1894. The new organ attracted considerable attention in the press and was the subject of several advance notices, which included the claim that its innovative mechanism would not be affected by climatic changes.

The missionary spirit of this pioneer church led to the expansion of Methodism throughout the district; many other Winnipeg Methodist churches owed their beginnings, either directly or indirectly, to Grace. Perhaps because of its activism and acceptance of diverse opinions, Methodism attracted a number of prominent social reformers, businessmen, newspaper writers, and politicians as supporters. The Methodists also erected the Wesleyan Educational Institute near the parsonage of Grace Church in 1873; in 1877 they established Wesley College, now the University of Winnipeg.

Grace Methodist Church, circa 1872. The church opened in September of 1871.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

On 8 April 1867 some of the residents of the small hamlet at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers met in the Court House to organize a parish, and a building committee was appointed. At first, religious services were held in the Court House, just outside the enclosure of Fort Garry, and afterwards in the upper level of Red River Hall near the corner of what are now Portage Avenue and Main Streets. The large numbers of people that crowded into this fragile structure required the use of wooden poles as temporary supports for the floor to prevent the assembled congregation from falling into the store below. The small congregation commenced work on building their own church at the corner of Avenue and Garry Street on land donated by the Hudson’s Bay Company. However, the enterprise was thwarted by a violent windstorm that destroyed the incomplete structure and killed a workman who was sleeping there overnight. Starting over, the congregation successfully completed a simple and unpretentious wooden structure that was opened for public worship in two services on 4 November 1868. The first vestry of the church that was constituted five days later included the rector, The Venerable Archdeacon John McLean, and other prominent members of the community.

By 1870 the church was already too small for the expanding congregation, so steps were taken to enlarge the building to accommodate 350 persons; this was accomplished by Christmas Day of that year. A later cleric, Rev. Canon Grisdale of St. John’s College, promoted a new church with a capacity for 450 worshippers; it was opened on 11 November 1875, when Rev. O. Fortin was inducted by the archbishop of Rupert’s Land, but only the chancel and transept were completed at that time.

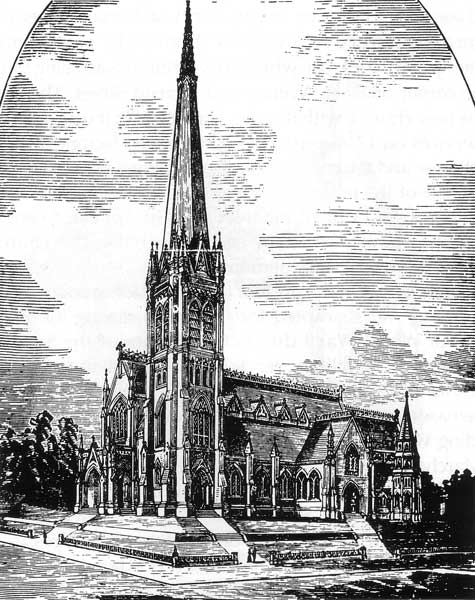

The population of the community increased so rapidly in the following years to the extent that even the addition of the nave was insufficient to handle the influx of people. Accordingly, in 1879 lots for the erection of a new building were purchased at the corner of Donald and Graham Streets, and construction plans were approved. The new church was formally opened on 4 August 1884 in the presence of a large gathering that included the archbishop of Rupert’s Land and other local and visiting ecclesiastical dignitaries. The building is a landmark in the history of Winnipeg’s architecture, characteristically Gothic in style, with its wide nave, unobstructed by piers, and spanned by an elaborate hammer-beam roof.

Holy Trinity, like some other Anglican parishes, undertook local missionary work in its early years: St. Matthew’s Mission and St. Barnabas Mission, both in 1896, and St. Luke’s in 1897; eventually these formed their own independent parishes.

The church had several pipe organs over the years. The first was a two-manual, 24-stop instrument built by S. R. Warren & Son, Toronto, in 1878; it was enlarged to three manuals, 39 stops, when the church moved to a new location in 1884, and additions followed in 1892. In 1912 the Canadian Pipe Organ Company, St. Hyacinthe, Quebec, installed a four-manual, 50-stop instrument that was described at the time as “the finest organ in the Canadian West.” It was enlarged, with additions to 53 stops, by Casavant in 1950.

Holy Trinity Anglican Church, circa 1884. Located at the corner of Donald Street and Graham Avenue,

Holy Trinity is now a national historic site.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Churches - Holy Trinity (3) 20 (N5063).

It will be recalled that Rev. John Black, who had served as minister at Kildonan Presbyterian Church in 1851, had been ordained at Knox Church, Toronto, shortly before he arrived at the Red River Settlement, a fact that was both coincidental and prophetic. In 1862 William Ross, a brother of Mrs. Black and the first Postmaster at Winnipeg, was interested in opening a Presbyterian service at Fort Garry. Therefore, in 1868 a site was secured at the corner of Fort Street and Portage Avenue. As construction proceeded, Black appealed to friends in the east, and a gift of $400 was sent by Knox Church, Toronto. Appropriately, the new congregation adopted the name “Knox” for their new church. Although construction was interrupted by the troubled times of the Riel Rebellion, a small wooden structure was erected in 1870 after order had been restored.

The congregation soon outgrew the capacity of the original building, so the structure was moved to the rear of the lot, and a new imposing building, capable of seating 800 people, was erected in 1879 at a cost of $26,000.

Then, in Winnipeg’s boom year of 1881 some lots were purchased on Hargrave Street, north of Portage Avenue, where a large structure, known as “Knox Hall,” was erected as a temporary measure while a new church was being built at the corner of Ellice Avenue and Donald Street. The cost of this new church, with the site, was $60,000; it was opened for services on 17 August 1884. Unforeseen factors such as street noise and the encroachment of business eventually led to the sale of the property. A new site was secured in 1913 at the corner of Edmonton Street and Qu’Appelle Avenue, opposite Central Park, at a cost of $80,000. The church building eventually was demolished.

Construction of the present church building was started in 1914 but was disrupted for two years during the early period of World War I due to the absence of the Scottish stonemasons on military service with Canadian or British forces, as well as the lack of financing. With the return of the stonemasons and refinancing by the Board of Managers, the building was completed in time for the opening service on 25 March 1917. The building is a magnificent example of Gothic Revivalist design. Using steel-frame construction, the massive stone walls, with their large decorated Gothic windows, avoid the necessity of cumbersome buttresses.

Throughout the years the women of Knox have given continuing support to the work of the church. As early as 1873 a small group was organized to assist the general work of the congregation; by 1876 they were first known as “The Charitable Aid Society,” replaced by the “Ladies Aid” and “A Women’s Missionary Society.” In 1884 they sent clothing and food to Indian reserves and to white settlers who had suffered severe losses in prairie fires. Much later, in 1961, the “Women’s Missionary Society” formed circles to encourage friendship and to distribute responsibility for social welfare and community activities.

Knox Church has had several pipe organs throughout its history. The first, by an unknown maker, was brought from the United States in 1882. The third church acquired a two-manual Warren instrument around 1885. A three-manual, 32-stop Casavant instrument was acquired in 1906 and moved to the present church in 1917; a new console and additions in 1949 increased its size to 34 stops.

On 6 April 1876 the Most Reverend Alexandre Tache, archbishop of St. Boniface, promulgated the establishment of St. Mary’s Parish, and Rev. Father Baudin became its first parish priest. Four years later, on 15 August 1880, Archbishop Tache blessed the cornerstone of the permanent St. Mary’s Church, the first edifice for Catholic worship in Winnipeg. The church was dedicated on 4 September 1881 although it was not fully completed for several years. The spiritual life of the parish thrived under a succession of priests until the church was consecrated on 25 September 1887 by the Most Reverend Edouard Charles Fabre, archbishop of Montreal, assisted by three bishops who came from other parts of Canada. Three thousand citizens of all creeds assembled either in or around the church for this significant event.

By 1895 the church was too small to accommodate its growing congregation so it was enlarged and beautified under the direction of Rev. Father Didace E. Guillet, who had come to St. Mary’s after a distinguished career on the staff of the University of Ottawa. A new presbytery, which became the residence of the archbishop and parochial clergy, was built at the same time.

In the early 1900s the rapid growth of Winnipeg and the expansion of business in the vicinity of the church raised the question of moving the church to a better location, preferably in a residential district within the parish boundaries. Although the property was acquired and a loan secured, these plans were abandoned during the war years following 1914 and were never renewed. Nevertheless, in December 1915 it was announced from Rome that an archiepiscopal See was to be created in Winnipeg, with jurisdiction subject to the Holy See. The first archbishop was the Right Reverend Monsignor Sinnott, who for many years had been the secretary of the Apostolic Delegation at Ottawa; he arrived in Winnipeg on 23 December 1916. In his inaugural address on 8 December 1918 he announced that he had selected St. Mary’s from all the Catholic churches in Winnipeg to be a cathedral church. The cathedral was completely renovated in the early 1950s, including the installation of stained glass windows and new pews.

St. Mary’s had two pipe organs. The first, a two-manual, 18-stop instrument, made by Louis Mitchell of Montreal, was installed in 1883. The inaugural concert on 20 April 1883, involving the church choir and several soloists, was unusual in one respect: Samuel Mitchell of Montreal, the father and associate of Louis Mitchell, who had also installed the first organ in St. Boniface Cathedral in 1875, was the featured recitalist. Casavant Freres installed the second organ, a two-manual, 18-stop instrument, in 1918; it was later renovated and enlarged to 16 stops in 1957.

The Congregational Church, which derived from the seventeenth-century English Puritan tradition, entered the missionary field in western Canada much later than the other denominations. First Congregational Church was organized in August 1879 upon the arrival of Rev. William Ewing, who remained for only two years. For a time, meetings were held in the home of a parishioner, then at other various locations around the city, including some churches.

Early in 1882—Winnipeg’s most famous boom of 1880-1883 was at its peak—property was acquired from the Hudson’s Bay Company and plans were developed for a church building on Hargrave Street at Qu’Appelle Avenue. The church was completed in 1882 and dedicated on 8 December 1882. The presiding minister, Rev. J. B. Silcox, became a popular orator who was involved in various public campaigns for social improvement. (A later minister was Rev. Stanley Knowles, another social activist, who became Member of Parliament for Winnipeg North Centre.) The church was renamed Central Congregational Church in 1887. It ranked in size, membership, and importance with the major churches of other denominations, and they were all near neighbours.

On account of the large size of its auditorium, the church was frequently used for a variety of public events, including performances by visiting noted musicians and speeches by prominent figures such as a British feminist, a Russian grand duke, and an American political orator. A local mayoralty contest was held there, too.

The church building presented a conventional ecclesiastical appearance with a body pierced by long Gothic windows and a gable roof dotted by triangular clerestory dormers. Although the building was enlarged in 1905 to accommodate the growing congregation and its multiple uses, by the 1920s the structure’s large creaking gallery became unstable, so a decision was made to demolish the unsafe building, which was done in 1936.

Central Congregational Church had only one pipe organ in its brief history: a two-manual Warren instrument installed around 1883.

In 1883 the site that was selected for All Saints’ Church on the north side of Broadway Avenue was still prairie land, for there were only a few scattered buildings in the vicinity. The intention was establish a church that would place more emphasis on the musical and ritualistic aspects of worship than was customary in Anglican churches in Winnipeg at the time. One of the most active proponents in bringing this idea to fruition was C. J. Brydges, the Land Commissioner of the Hudson’s Bay Company and Honourary Treasurer of the Synod of Rupert’s Land. Construction of a church building began immediately following the election of churchwardens and vestrymen in August 1883. The frame building had ecclesiastical proportions in the English Gothic style and was capable of seating 450 people.

The first service was held in the new building on 15 February 1884, when the sermon was delivered by the Most Reverend Dr. Robert Machray, subsequently archbishop of Rupert’s Land and primate of All Canada. An anonymous letter to a Winnipeg newspaper complained:

Ch. Of All Sts. has just been formally opened by the Bishop of Rupert’s Land. 2 things in connection with the church and its opening are public property, and neither is creditable to those concerned. ... [One] matter is the illegal, immoral lottery which the church is sanctioning for the benefit of the organ fund. A bed quilt or something of the sort is to be gambled for, the proceeds of the swindle to go to the church. All Saints is improperly named, it should be called All Sinners. To expect true Christianity in a fashionable church seems as absurd as to expect to find decency in a monkey house. (Winnipeg Siftings, 23 February 1884.)

In the early days the church became known as the “Garrison Chapel” since soldiers of the Royal Canadian Dragoons (later Lord Strathcona’s Horse), stationed in their nearby barracks, invariably attended the morning services.

The growth of the congregation, as well as the increase and spread of the city’s population generally, required the construction of a large addition (sometimes facetiously referred to as “the summer kitchen”) in 1912, but the prospects of a wholly new church had to be delayed until after World War I. But even by 1914 the church, which thirty years before had been relatively isolated on the prairie, came to be known as a “downtown church.”

While the war was going on, the question of a memorial to those members of the congregation who had lost their lives in the conflict was resolved through a gift of the Women’s Guild for the purchase of a new pipe organ. A large three-manual, 37-stop instrument by Casavant Freres was installed and dedicated on 6 September 1917, replacing a two-manual, 16-stop Warren instrument that had served the congregation since 1891.

Early in 1925 the question of a new church building was renewed by a decision of the City of Winnipeg to extend Osborne Street through the church property, necessitating the removal of the entire church building. A new site located just west of the existing church was purchased and excavation began in June 1926. The cornerstone of the new church was laid on 25 September 1926 by the Right Reverend A. F. Winnington-Ingram, Lord Bishop of London, assisted by the Most Reverend S. P. Matheson, archbishop of Rupert’s Land. Besides the current rector and two immediate past rectors, twenty-two archbishops and bishops of the Church in Canada and many visiting clergy from other dioceses were present on that occasion. The dedication of the church on 23 December 1926 was so well attended that many were unable to gain admission.

The Casavant organ from the old church was reinstalled in the new building, and it served the musical needs of the congregation until it was enlarged and rebuilt in time to be dedicated in March 1959 in connection with the seventy-fifth anniversary of the parish.

All Saints Anglican Church, 1886. This original wood frame church on Broadway was replaced by the present stone building in 1926.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

In 1887 the inhabitants of the small settlement of Fort Rouge felt the need for a church of their own, for the nearest Presbyterian church was Knox, a long walk before the days of streetcars or automobiles. Chief Justice Taylor, a prominent elder of Knox, was the leader of a group of residents of his neighbourhood along the south bank of the Assiniboine River who proceeded to fulfill this dream. A lot was chosen at the corner of River Avenue and Royal (now Pulford) Street, and a small frame church seating about 150 people was built at a cost of $2,062.71; it was heated by stoves and lighted by coal oil lamps. The new building was soon free of debt, and it was dedicated on 8 August 1887. The first minister was Dr. Andrew Baird, a staff member of Manitoba College, who agreed to serve the church in addition to his regular college duties. The board of management, which included Chief Justice Taylor, chose the name “Augustine.” Members of the Taylor family served Augustine in many ways: Chief Justice Taylor was clerk, treasurer, and usher; his wife led the choir and ladies’ groups; his two sons built fires and tended the lamps; and his two daughters swept and dusted.

The congregation had grown sufficiently by 1891 for the church to engage a full-time minister: Rev R. G. McBeth served from 1891 to 1900. During his time new wings were added to the church and various improvements were made. Dr. Gilbert B. Wilson, a familiar figure in the area who gained support for various church affairs, succeeded him. The progress achieved under his devoted service dictated plans for a new church, so it was decided to move the existing church to the rear and to build on the same site. Lady McMillan, wife of the lieutenant governor, laid the cornerstone in June 1903, and the new church was dedicated on 16 October 1904. The commanding tower and 53-metre spire of the Gothic structure, with its textured limestone facing, dominated the district. The cost of the building was $55,000. In 1909 the old church was replaced by the Guild Hall at a cost of $30,000; it was used as a Sunday School, with an enrolment of over 500.

Throughout the ensuing years the people of Augustine were active in church-related affairs at home and abroad. Missionary activities in the city included establishing a mission church in the Riverview area of Winnipeg and assisting a similar project in the Norwood area. In the early 1900s church members, both men and women, went to India, the Philippines, Korea, and China. By 1908 the total donations to home and overseas mission amounted to over $20,000. In all areas of activity Augustine was a very busy place in the 1930s and later. During the flood of 1950 the church was the relief centre for the area.

Music in the church was a strong activity in all periods. A three-manual, 28-stop organ built by D. W. Kam, Woodstock, Ontario, was installed in 1905 at a cost of $4,000, and it has remained relatively unaltered although it has been refitted and renovated several times in its long history. The prominent American organist Clarence Eddy, who had opened more organs than any organist of his day and performed at many world fairs, played two recitals for the opening of the Augustine organ in February 1905. The Canadian organist Lynwood Farnam, who became a legend in his own time, performed on the Augustine organ several times between 1905 and 1909. Other noted organists have given recitals on this instrument over the years.

Fort Rouge Methodist Church, the earliest founding church of Crescent Fort Rouge United Church, began as a mission congregation of Grace Methodist Church in 1883. Early services were held in temporary locations such as Pembina Public School (later renamed Gladstone School) and a small frame structure on the corner of Spadina (now Stradbrook) Avenue and Joseph (now Scott) Street. When the new minister Rev. Enos Langford was appointed he worked quickly to have a building erected that would serve the needs of the expanding congregation. The new church, located at the corner of Scott and Maria Streets (later Spadina, still later Stradbrook), was dedicated on 21 August 1887 in morning and evening services conducted by several clerics from Manitoba and one from Toronto. A short while later a small frame parsonage was built on the eastern portion of the church property. Several years later it was replaced by a more substantial brick residence.

During the ministry of Rev. J. H. Morgan (1903-1907) the size of the congregation increased to such an extent that a larger and more permanent building was needed. Because of. the number of students enrolled, it was decided to complete the Sunday School portion first. The Official Board purchased vacant property at the corner of Nassau Street and Wardlaw Avenue, and architectural plans were prepared; the new section was opened on 27 May 1906 with appropriate exercises. The cost of constructing and finishing the building amounted to $24,000 on land valued at $15,000.

In the early spring of 1910 ground was broken for the church auditorium portion, and the cornerstone was laid on 4 June 1910 by Rev. J. W. Sparling, principal of Wesley College, and Mrs. Manlius Bull, one of the charter members of the church. Following the completion of construction on 1 April 1911, the opening program of the new church began the next day. It included a series of special events spanning a three-week period: a public lecture on Ireland (admission 25 cents) by a visiting cleric from Toronto, a congregational supper, a choir concert, addresses by several local clerics, a prayer meeting, and a young people’s entertainment and social. The dedicatory service took place on 16 April 1911 with special services each evening during the week.

Following the design of the Sunday School building, the architectural style of the church is Romanesque Revival, incorporating rounded arches into the straight edges of bright red brick walls, trimmed with Tyndall stone. Two towers flank the front of the building with its twin entrances. The auditorium has a groined ceiling supported from four columns on each side; there is a gallery around three sides. The total seating capacity is 1,059. The cost of the new building was $60,000.

The first pipe organ of the church was installed in the Sunday School building in 1906; it was a two-manual, 17-stop Casavant instrument, later removed. A larger three-manual, 33-stop Casavant organ was installed in the main church building in 1911.

The introduction of Methodism in western Canada and the activities of Rev. George Young, following his arrival in Winnipeg in 1868, have been chronicled in connection with the establishment of Grace Methodist Church, earlier in this article. It was obvious to many people at Grace that there was a need for a Sunday School in the west end of the city, so a committee of prominent men from Grace purchased four lots at the corner of Broadway Avenue and Furby Street and let a contract for a building. A small frame structure seating 200 was dedicated on 30 October 1891; Sunday School started about a week later. The first regular service in the new Young Memorial Methodist Church was held on 17 January 1892, conducted by Rev. Andrew Stewart of Wesley College, attended by 40 people.

The rapid period of growth of Young Church rendered the original building too small, so an additional wing was added in the summer of 1892. At the same time, the church received its first regular minister, Rev. J. H. Riddell, who retained his position as assistant minister at Grace Methodist Church until 1894. Further expansion of the church building took place in 1902 and 1904 to accommodate the larger congregation. Additional lots were purchased adjacent to the existing site, and plans were drawn up for a magnificent new building. The cornerstone for the new Young Church was laid in the summer of 1906. The first portion facing Broadway Avenue was built in 1907, containing the sanctuary, Sunday School rooms, offices, and clubrooms. The first service in the new structure was held on 21 Apri11907, when the new two-manual, 16-stop Casavant pipe organ was heard for the first time. In 1910 construction was begun on the east wing facing Furby Street. The formal dedication service for Young Church in its final form was on 19 March 1911.

The centralized plan of the church was based on Roman temple layouts, a style that was common in Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian churches throughout North America between 1840 and 1900. Under the soaring groin vault the pews of the auditorium formed a semicircle around the pulpit. The church was destroyed by fire on 27 December 1987; it was later replaced by a building of contemporary architectural design that incorporated the tower of the former building. The transformation was completed with the first service on 24 October 1993.

The present organ is a two-manual, 29-stop instrument by Orgues Letourneau, St. Hyacinthe, Quebec, installed in the same year.

With dropping membership and the evolving nature of the neighbourhood, the function of the church changed in recent years. The new designation, Crossways In Common, includes Young United Church, Hope Mennonite Church, West Broadway Community Ministry, and several social outreach agencies.

Interior of Young Methodist Church, no date. Built in 1911, the church was destroyed in a spectacular fire in December 1987.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

On the Sunday afternoon of 29 October 1887 Mrs. George Murray noticed some children playing in the open field behind Furby Street, called them into her home, and told them some religious stories. Her “Sunday School” continued for two years, when her band of forty children was taken over temporarily by Knox Church. The group migrated to several other locations in the area as it grew in strength. The West End Mission, as it was now called, occupied a building known as the Children’s Home on Portage Avenue from 1890 to 1892 until a site for a church building was selected at the corner of Portage Avenue and Spence Street. A small wooden structure, seating about 250, was erected at a cost of $1,700, and public services began on 16 October 1892. A year later the Mission was formed into a congregation with thirty-three members on the roll. The church building was enlarged in 1894 and again in 1895 to accommodate the needs of the vigorous young congregation. Rev. Charles W. Gordon took charge of the Mission on 5 August 1894, after a year’s study in Edinburgh, although he was not formally inducted until 24 May 1897. Under the inspired leadership of Rev. Dr. J. M. King, Principal of Manitoba College, the whole congregation was organized into a Mission Association. Its activities included a Women’s Foreign Missionary Society, a Boy’s Brigade, and a Sunday School. The full-fledged congregation, now numbering 157 members, adopted “St. Stephen’s” as its name.

In 1902 it was decided to proceed with the erection of a permanent Church Home, and a cornerstone for the new building was laid on 3 September 1902 by Mrs. Murray and Mrs. Gordon. The new stone church, costing over $50,000, was dedicated on 21 June 1903.

Church activities in the early 1900s increased to include the support of a foreign missionary in India, organization of the Women’s Home Missionary Society, expansion of the Sunday School, and establishment of two missions: one on Home Street and another on Clifton Street, both of which eventually became self-supporting and developed into independent churches (the latter as Chalmers Church). These early years witnessed a new and important aspect of church work, the St. Stephen’s Brotherhood, which served as a model for other congregations in the city as the Presbyterian Brotherhood of Winnipeg, and also for the General Assembly of the Canadian Church. Work among the young expanded to the extent that a large Church House was constructed on Young Street that became an active centre for religious, social, and athletic activity; in 1912 the Sunday School section alone had a membership of 836.

During the years of World War I the women of the congregation sent weekly boxes of clothing and supplies to their servicemen overseas, in addition to providing entertainment for soldiers in Winnipeg. About 400 men of the congregation served in all branches of the armed services and some of them achieved high military ranks. One of these was the minister, Rev. Dr. Charles W. Gordon, who acted as Chaplain to the 43rd Battalion Cameron Highlanders starting in May 1915; he served with them in many major battles in France. Early in 1917 the Canadian government recalled him for a special assignment of a public relations nature in the United States and Great Britain; he returned to his congregation at St. Stephen’s in the fall of 1919.

Rev. Gordon was perhaps best known under his alias, Ralph Connor, the prolific and best-selling Canadian author of the early twentieth century whose works won him fame and a wide audience. His novels combined adventure with religious messages and wholesome sentiment; they included Black Rock (1898), Sky Pilot (1899), The Man from Glengarry (1901), The Prospector (1904), and many others.

St. Stephen’s had two pipe organs. The first, by an unknown Toronto maker, was acquired from the Winnipeg College of Music in 1903; the second was a three-manual, 26-stop Casavant instrument installed in 1906 and enlarged to 32 stops in 1911.

Following the amalgamation of St. Stephen’s with Broadway United Church in 1927, the church building was purchased in the following year by Elim Chapel, which had begun as the Ellice Avenue Mission, a project of Westminster Presbyterian Church in 1910.

St. Matthew’s originated as a mission church of Holy Trinity Church in 1896 when meetings were held in a family home, conducted by students from St. John’s College. A year later a small wooden church was erected at the corner of Sherbrook Street and Ellice Avenue; it was opened in May 1897 by Archbishop Machray. An early leader was R. B. McElerhan, an accountant who served the mission on a voluntary basis until 1900 when he enrolled at the University of Toronto and Wycliffe College to study for the ministry. When the mission became independent of Holy Trinity, Rev. H. St. George Buttrum became the minister of the church. Six years later Rev. McElerhan, now a fully qualified minister, returned to be the rector of St. Matthew’s. Under his leadership the church experienced vigorous spiritual development that emphasized work among young people, and the Sunday School became the life of the parish. Missionary work was expanded to include contacts in India and China.

In 1908 the existing church was demolished to make way for a larger red brick building, officially opened on 10 January 1909. However, attendance at church and Sunday School increased to such an extent that the advisability of erecting a new church was discussed at an annual meeting of the vestry in 1912. On 7 May 1913 the cornerstone of the new St. Matthew’s was laid on its present site at the corner of what are now Maryland Street and St. Matthew’s Avenue. Rev. Dr. W. H. Griffith Thomas of Wycliffe College, Toronto, conducted the opening service on 9 November.

Rev. McElerhan received much recognition for his work: honourary Canon in 1917, Archdeacon of Winnipeg in 1920, honourary Doctor of Divinity degree from St. John’s College in 1920, and the same degree from Wycliffe College in 1927. In 1930 he resigned to become Principal of Wycliffe College. Before leaving St. Matthew’s, Archdeacon McElerhan instituted a fund for a memorial organ in memory of the men of the congregation who had lost their lives in World War I, and he returned from Toronto for its service of dedication on 26 October 1930.

In 1944 the church building was razed by fire, but within three years it had been rebuilt to much the same plan. The new building was dedicated in 1947 and finally consecrated in 1953. The large-scale building, designed to accommodate a congregation of more than 1,500 people, is noted both for the quality of its ornament and its spectacular vault that dates from renovations carried out following the fire.

The first organ in St. Matthew’s was acquired in 1910 but nothing is known concerning its maker or size. The memorial organ of 1930, a three-manual, 40-stop instrument built by Casavant, was destroyed in the 1944 fire; its replacement with the same specifications was installed by Casavant in 1948.

In the late 1880s the nearest Anglican church attended by residents of the Fort Rouge district was Holy Trinity. While it was within easy walking distance for adults, it was too far for children to go to Sunday School. The curate of Holy Trinity therefore suggested to one of the lay readers of his church that a Sunday School be started in Fort Rouge, and a suitable meeting place was found in a vacant store on Maria (now Stradbrook) Avenue. As attendance grew, a parishioner offered her house, which soon was filled to overflowing. Funds were secured to erect a Sunday School building, which was formally opened in 1891 by Archbishop Machray, assisted by the bishop of Mackenzie River and the rector of Holy Trinity.

A mission for adults was established at the same time, and regular Sunday services commenced on 17 October 1893. For a while, J. A. Richardson, a theology student at St. John’s College, who later became the first rector of St. Luke’s, conducted services. With the growth in population, church-related activity expanded sufficiently in the next four years that Archbishop Machray established the new parish of St. Luke’s on 14 April 1897.

Within a few years the congregation decided on the ambitious project of erecting a stone church, so lots were purchased on Stradbrook Avenue, plans were drawn up, pledges and contributions were obtained, and a cornerstone was laid on 25 July 1904. The first service in the new building was conducted on 19 February 1905 by the Right Reverend Dr. S. P. Matheson, then administrator of the Diocese of Rupert’s Land. The church is relatively conservative in style, following medieval tradition. Its broad windows, horizontal emphasis, and Gothic elements reflect English vernacular influence. The oversize buttresses of the porch reflect the then current interest in the expressive use of materials.

The growth of the district of Fort Rouge south along Osborne Street indicated that a mission would be necessary to accommodate those living along the Red River, so the new mission church of St. Alban’s was opened on 8 September 1907 (it became a separate parish in 1912). About the same time, St. Luke’s raised enough funds to support its own missionary in Japan.

Great forward strides in church affairs were achieved during the long incumbency of Rev. Canon W. Bertal Heeney, the fourth rector of St. Luke’s, 1909-42. Within a month after his arrival he promoted plans for enlarging and beautifying the church that included extending the chancel, installing new pews, providing various interior furnishings and equipment, building basement classrooms, providing space for a new organ, and erecting a square tower at the east end. The first service in the completed church was conducted by Archbishop Matheson on 12 December 1910, when the organ was played for the first time.

The eight tower bells, cast by the historic firm of Mears and Stainbank of London, were placed in the tower in January 1911. The bells, along with the tower clock, were presented by Sir Augustus and Lady Nanton. The enlarged east window, with its representation of Da Vinci’s Last Supper, was installed early in April 1911, the gift of Sir Douglas and Lady Cameron. Later improvements included building a rectory and parish hall, completed in 1914.

The rector of St. Luke’s was the chaplain of the Winnipeg Grenadiers during World War I, and in 1923 an oak cross that had been set up on Vimy Ridge in memory of soldiers killed during the fighting was brought from France and handed over to the church for safekeeping. Two other war memorials include a brass honour roll, and a mural painted by Frank H. Johnston A.R.C.A. that commemorates those Winnipeg Grenadiers who served in the war. The last important addition to the church was the exquisite rood screen, erected at Easter time 1928 in memory of Sir Augustus Nanton by his widow and children. The church was consecrated on 20 April 1947 by the Most Reverend L. R. Sherman, archbishop of Rupert’s Land.

The 1910 organ mentioned above was a three-manual, 30-stop Casavant instrument, later enlarged to 36 stops. In 1953 it was reconstructed by the English builders, Hill, Norman & Beard, to four manuals, 61 stops, and later revised to 59 stops in 1979 by local organ technicians R. Buck & B. Mantle. Solid-state capture action was added in 2001. The instrument remains the largest pipe organ in Winnipeg.

It was in the fall of 1892 when eighteen members of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church discussed the possibility of forming a more centrally located congregation for the growing community. Permission was granted and the work of establishing a new church began: its first service was held on 1 January 1893 in Victoria Hall, later the Winnipeg Theatre, on Notre Dame Avenue, attended by more than 200 people. A few days later, the new congregation chose the name “Westminster” from a list that included St. Paul’s, Chalmers, Tabernacle, Central, and People’s Church. Construction of the permanent church at Notre Dame Avenue and Charlotte Street commenced, and first services were held in the new church on 31 December 1893. Formal dedication services followed on 5 and 12 August 1894. By this time a women’s foreign mission society was active, and a club for young men engaging in athletics and debates was formed several years later.

In response to rapid increases in the city’s population, in 1909 Westminster set up a Sunday School in the southwestern part of the city at 69 Furby Street, and it was decided to have a new church building in that general area. The site chosen was at Maryland and Buell (later Westminster Avenue) Streets, and the cornerstone was laid on 2 April 1911. On that occasion the governor general, the Right Honourable Earl Gray, commented, “the absence of sectarian prefix ‘Presbyterian’ perhaps justifies one in inferring that your church here teaches a greater importance of religious unity than sectarian difference.” The opening service of dedication took place on 16 June 1912. The final cost of the church was $200,000.

The building’s design in the Beaux-Arts/English Gothic Style is reminiscent of cathedrals of Europe. The walls and buttresses are of uneven, coursed, rough cut stone, while the staircases, coping, window accents, and buttress caps have a smooth finish. Pinnacled towers of unequal height flank the two central doors with their Tudor arches. The front facade displays an impressive rose window. There are five other stained glass windows in the church.

In the early years of World War I Westminster was active in several fields: three missionaries were posted in China and India, a club was formed for young women contemplating missionary work, and a social-recreational centre served more than 3,000 service people away from home in 1914 alone.

A significant event in Westminster’s second twenty-five years was the union of the Methodists, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists into the United Church of Canada on 10 June 1925; each congregation held its own vote. Of Westminster’s 1,133 members, 569 voted for, 129 against; of those opposed, 124 then left the church. In this period Westminster continued its work with missions at home and abroad, and the Ladies Society financed a hospital in Eriksdale, which opened in May 1926.

Of Westminster’s clerics, perhaps the most charismatic was Rev. Dr. J. S. Bonnell, under whose leadership (1929-1935) the church maintained its tradition of increasing membership and balanced budgets, even in hard and uncertain times. Dr. Bonnell often held services in a packed church and for an overflow audience in the Tivoli Theatre across the street; his messages were also broadcast on a local radio station.

During World War II Westminster was again active, setting up a War Service Unit to coordinate the war work of all church organizations, and establishing other social groups in support of the war effort. Westminster’s first theological candidate graduated from United College in 1939. The church was declared free of its mortgage debt at the Fiftieth Annual meeting on 19 January 1943. In May 1991 Westminster was designated as a Heritage building by the provincial government.

Westminster Church had a reed organ until 1894, when it acquired the discarded Warren pipe organ from Grace Church. Then, five years later, it acquired a two-manual, 24-stop Karn instrument. In 1912 the church installed a large four-manual, 49-stop Casavant organ in its new building at a cost of $10,500. This present organ, modified throughout its history to 54 stops, is the grandest organ in Winnipeg in the Romantic tonal tradition. For this reason it has served as the location for many concerts and recitals by local players and world-renowned organ virtuosos over the years. Since 1989 the church has sponsored the Westminster Concert Organ Series, in which guest organists from some of the most famous churches in the world have performed.

Notre-Dame des Prairies, or Our Lady of the Prairies, is on the fringe of this study of churches on account of its geographical and social isolation from the affairs of Winnipeg. Nevertheless, it deserves a brief mention on account of its uniqueness in the area.

The Trappists, a branch of the Cistercian Order, was founded in 1098 by three reformist Benedictine monks who observed the rule of St. Benedict: charity, obedience, and humility. They derived their name from the village of La Trappe, Normandy, where a monastery was established when peace was restored after the French Revolution. When the Trappists first came to Canada they established a centre in Quebec in 1881 under the guidance of the Abbot of the Trappist Monastery of Bellefontaine, France. The initiative for the monastery in St. Norbert, a district south of Winnipeg, came from Archbishop Tache of St. Boniface and Father Richot, parish priest of St. Norbert, following a meeting with the Abbot of Bellefontaine. For many years Father Ritchot had hoped to see a group of Moines Blanc (White Monks) settle in his parish, and a quiet secluded piece of land along the LaSalle River had been secured for that purpose. The first site of the monastery buildings was a peninsula on the west bank of the river, not far from its junction with the Red River.

The first monastery building, a three-story wooden structure with a tiny bell tower, was constructed in the summer of 1892. The first group of four monks—two from France and two from Quebec—arrived on 9 September 1892. Faithful to their rule of poverty, the monks subsisted on what they raised from the land, so agriculture and animal husbandry (even though the monks were vegetarians) were of primary importance; they used only the most up-to-date equipment for their agricultural activities. Their self-sustaining community included a bakery, a shoemaker’s shop, a forge, and a sawmill. They constructed stables, granaries, equipment sheds, and chicken coops, using local materials. In 1906 they set up an apiary and began to sell their famous honey.

The Trappists of Our Lady of the Prairies lived a simple and strict communal life, away from the distractions of the secular world. The secluded grottos, thick stands of oak and willow, and expanse of rich farmland surrounding the monastery provided the ideal setting for meditation.

When the original quarters became too small, the monks began the construction of a new church in the summer of 1903, but it was not completed for several years. The large Romanesque Revival structure, 43 metres long and 18 metres wide, built of brick and Manitoba stone, was capped by a silver-domed bell tower. It had the round-headed windows and rounded cross-vaulted roof typical of the style. Inside, seven small chapels were used for private masses. Many of the religious ornaments and statues were gifts from France, but most of the interior furnishings were crafted by the monks themselves.

The construction of a three-storey monastic wing for living quarters was completed in 1905; it matched the church in colour, materials, and brick detailing. By 1912 there were forty-seven monks in residence. This building served as a guesthouse after the old wooden monastery was destroyed by fire. In 1955 the monastery was raised to the dignity of an independent Abbey.

By the 1960s the monks anticipated that increasing urbanization would intrude on their life of peaceful solitude, so they planned the transfer of their estate to another location. Between 1975 and 1978 the Trappists moved to a new monastery located between Holland and Bruxelles, Manitoba, 145 kilometres southwest of Winnipeg, where they continued their farming operations on a smaller scale. Fire gutted the original church and residential wing in 1983. The ruins of the old church still remain, a symbol of the first refuge of religious contemplation in western Canada.

The churches surveyed here exhibit a number of common features throughout their history. While many were deliberately established by the ecclesiastical authorities of particular denominations—Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist, and Congregational—others were the products of communal efforts on the part of people of particular denominational affiliations who came together to share their belief in the need for a centre of worship. A few originated as missions of established churches. Many early churches had humble beginnings in private homes, vacant stores, or rented property. Several congregations opened Sunday Schools before their main church buildings were established.

The dedicated and insightful leadership that emerged in such informal groups resulted in the erection of small wooden structures that soon had to be enlarged and expanded to accommodate the increasing population of Winnipeg in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The flourishing economy that accompanied this general growth stimulated the construction of the large and imposing buildings that still exist today as testimonials to the foresight, energy, and determination of their founding members.

Publications of the Historic Resources Branch: Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Tourism

Kildonan Presbyterian Church, 1981.

Our Lady of the Prairies, 1982.

The Red River Settlement, 1991.

St. Boniface, 1994.

St. James Church, 1985.

Background Report: St. John’s Cathedral Site in the Nineteenth Century. Prepared for Historic Resources Branch, by Kerry M. Abel, May 1985 (contains an extensive bibliography and numerous illustrations).

A Study of Anglican Church Buildings in Manitoba, by Kelly Crossman, 1989.

A Study of the Church Buildings in Manitoba of the Congregational, Methodist, Presbyterian and United Churches of Canada by Neil Bingham, Historic Resources Branch, Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Tourism, 1987, 289 pages.

Church publications (* in the Manitoba Legislative Library)

*All Saints’ Church, Winnipeg: One Hundred Years 1883-1983.

All Saints’ Church 60th Anniversary, 15 February 1884-15 February 1944.

*The Cathedral Story: A Brief History of St. John’s Cathedral, Winnipeg, in commemoration of its 50th Anniversary, 1926-1976, by Thomas F. Bredin. Winnipeg: Peguis Publishers, 1975.

Central United (Congregational) Church, by Murray Peterson. Seniors Today, 15 June 1996, p. 6.

*A Century of Caring 1883-1983, Crescent Fort Rouge United Church.

Elim Chapel Seventy-Fifth Anniversary 1910-1985.

History of St. Mary’s Parish, by F. W. Russell and Sisters of the Holy Names’ Centennial History, 1974.

In the Midst of the Years, History of St. Matthew’s Church, Winnipeg, 1934.

*One Hundred Years of Augustine 1887-1987, Centenary Anniversary, by Edith McCracken, 1987.

100 Years 1868-1968, Knox United Church, 1968.

*Our Church is Not a Building: An Oral History of Young United Church, by Tim Higgins, 1995.

Our First Half Century: The Story of St. Luke’s Winnipeg 1897-1947.

Silver Jubilee 1895-1920 of St. Stephen’s Winnipeg.

*Sixty Years and After: An Historical Sketch of Holy Trinity Parish, Winnipeg. Written for the most part by the late Venerable Archdeacon Fortin, O.J. Winnipeg: Dawson Richardson, 1928.

The Story of Kildonan Presbyterian Church 1851-1951. Second Printing (with addenda 1978).

“Three Score Years and Ten, Being the 70th Anniversary of the founding of Grace Church, Winnipeg, October 30th, 1938.

*Westminster Church 1892-1992.

Books

Hartman, James B., The Organ in Manitoba: A History of the Instruments, the Builders, and the Players. Winnipeg: The University of Manitoba Press, 1997.

Healy, W. J., Women of Red River. Winnipeg: Russell, Lang, 1923.

Hill, Robert B., Manitoba: History of Its Early Settlement, Development and Resources. Toronto: William Briggs, 1890.

Schofield, F. H., The Story of Manitoba, vol. 1. Winnipeg: S. J. Clarke, 1913.

Wells, Eric. Winnipeg, Where the New West Begins: An Illustrated History. Burlington, ON: Windsor Publications, 1982.

Page revised: 17 August 2020