by Shannon Bower

Winnipeg

Number 42, Autumn / Winter 2001-2002

|

“I hope that after my death my spirit will bring practical results.”

Louis Riel’s words as inscribed on the walls surrounding Marcien Lemay’s and Etienne Gaboury’s monument

Canada has been haunted by Riel’s spirit for over 130 years. Various historians have sought to illuminate the reasons why this particular spectre appears so frequently in the ideas of Canadians. In “The Myth of Louis Riel,” historian Douglas Owram documents a convergence of opinions regarding Riel, arguing that contemporary English-Canadian historians now portray him with the heroic terms that have always been employed by French, Métis, and Aboriginal commentators. [1] Donald Swainson has examined how many popular writers and cultural producers have ensured that Riel’s spirit not be allowed any repose, but be put quite deliberately to work: “by the mid-twentieth century ... Riel had become the ultimate Canadian example of the usable in history: he could be looked at in a seemingly infinite number of ways.” [2] In G. F. G. Stanley’s more flowery terms, “pour chaque Canadien, le véritable visage de Riel est celui dans lequel it se reconnaît....” [3] Importantly, it is not always a spectral countenance that contemporary observers are considering. The issue of recognition gains significance in light of the controversy surrounding the two statues of Louis Riel that have stood on the Manitoba Legislative Building grounds. Whether hovering as historical phantasm or incarnated as stone statue, the Riel that people recognize is linked less to his actual historical role than to the needs and desires of the various groups and individuals who seek to animate their struggles through the transcendent spirit of Louis Riel.

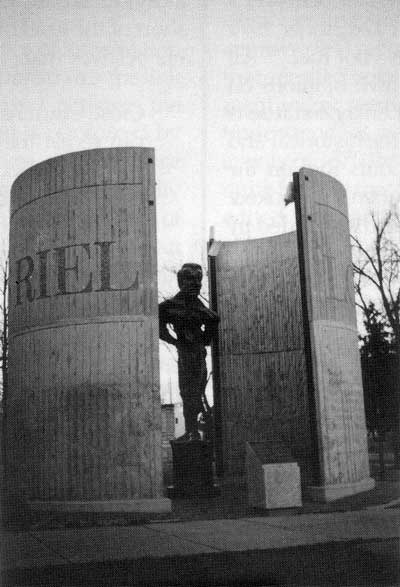

The idea of erecting a statue of Louis Riel on the Manitoba Legislative Building grounds seems to have emerged in conjunction with preparations for the celebration of Manitoba’s centenary in 1970. Following a public competition, the proposal submitted by Marcien Lemay and Etienne Gaboury was selected. Their monument consisted of an outer shell emblazoned with Riel’s name and several quotations from his writings, and a symbolic rendering of Riel in statue form between the walls. Through the juxtaposition of the politician and the man, this monument sought to capture the relentless tensions of Riel’s life. Unveiled on 31 December 1971, it garnered a mixed reception from Métis and non-Métis people alike.

The controversial statue of Riel by Marcien Lemay and Etienne Gaboury unveiled in December of 1971.

Originally located at the Manitoba Legislature, the statue was moved to the College Universitaire de St. Boniface in 1995.

Source: Robert Coutts

Over subsequent years, the statue proved a source of controversy. In the late 1980s, a proposed redevelopment of the rear grounds of the Manitoba Legislative Building led to a renewed dialogue regarding the statue between the provincial government and the Manitoba Métis Federation. What became a debate over the removal of Lemay’s and Gaboury’s work appeared resolved when Lemay agreed to the removal on the condition that he be commissioned to sculpt the replacement work. Between 14 and 27 July 1994, a group of individuals led by former MLA Jean Allard camped at Lemay’s statue to prevent its removal. Early in the morning of 27 July, the protesters were convinced to leave quietly, and the statue was removed. Nearly a year and a half later, on 30 November 1995, Lemay’s statue was rededicated on the grounds of College Universitaire de St. Boniface. Yet Lemay’s second rendering would never stand on the legislative grounds. Amid much controversy, Miguel Joyal, a Winnipeg artist, was commissioned to create the new statue. Joyal’s less volatile rendering was unveiled on 12 May 1996.

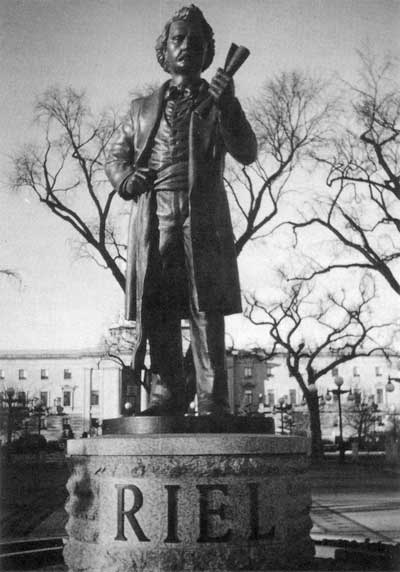

Statue of Louis Riel at the Manitoba Legislature. Created by Winnipeg artist Miguel Joyal,

the statue was unveiled in May of 1996.

Source: Robert Coutts

Due to the extensive media coverage accorded these events, it is deceptively simple to sketch their parameters with relative ease and accuracy. Yet between the lines of my brief summary lies a story that is not so easily perceived or expressed—the story of a community divided around the question of how Louis Riel should be remembered. Over nearly thirty years, diverse groups and individuals have been involved in various ways in the ongoing debate. Numbered among the groups have always been the Métis. Though Riel has proved, in Swainson’s terms, useable by all Canadians, it is ultimately only the Métis who are fundamentally entwined with Riel. Frances Kaye, in her article comparing the statue controversy in Manitoba to a similar series of events in Saskatchewan, asserts that Riel is “the inescapable national image of the Metis”. [4] This sentiment is echoed by Catherine L. Mattes in her examination of images of Riel. [5] While the existence of an incontrovertible link between Riel and the Métis is argued vehemently by Kaye and Mattes, it is acknowledged tacitly by Winnipeg’s daily newspapers. From 1968 to 1996, reporters for The Winnipeg Free Press and The Winnipeg Sun were always eager to secure comment from a Métis person concerning the latest statue controversy. Also, individuals tended to add credence to their opinions, in cases of both requested comment and volunteered opinion, through assertions of their Métis status. Métis identity provides some people with a perceptual position of singular significance from which to evaluate representations of Riel. Though he may be used by many, Riel is intimately and irrevocably connected with some. Any statue of Louis Riel must be understood as a representation of the Métis people.

As I examine a series of events that took place in Winnipeg during a 30-year period, I am preoccupied with the Métis who have lived and now live in this area. Associated in the broadest sense with an identity shared in common among individuals of mixed European and Aboriginal descent, the Métis community has been characterized by levels of geographic and intellectual unity that have varied both in response to internal pressures and, particularly, external conditions during 200 years of habitation in the prairie west. Jennifer Brown argues that a biological definition of Melds identity is insufficient, and asserts that Métis “refers to a distinctive sociocultural heritage, a means of ethnic self-identification, and sometimes a political and legal category, more or less narrowly defined.” [6]

In Winnipeg between 1969 and 1996, it was another definition of Métis that prevailed in many quarters. As my paper will demonstrate, the ways many people perceived the Métis community were situated within the parameters of colonial thought. Ann Stoler has argued that the metis of southeast Asia, as people “whose cultural sensibilities, physical being, and political sentiment called into question the distinctions of difference which maintained the neat boundaries of colonial rule,” represent a dangerous source of subversion to nineteenth-century colonial rule. [7] Despite temporal and geographic differences, the Métis of late twentieth-century Canada embodied a similar challenge insofar as they refused to remain confined to the conceptual and geographic spaces accorded to them by colonialism. Within the context of the statue controversy, the words and actions of individuals serve not only to reveal their attitude toward Riel and the Métis, but also to reflect their position within the entrenched social order.

Both statues attempted commemoration, and this shared purpose was of significance in the controversy. John Bodnar, in Remaking America, asserts that:

Because numerous interests clash in commemorative events, they are inevitably multivocal. They contain powerful symbolic expressions—metaphors, signs, and rituals—that give meaning to competing interpretations of past and present reality. [8]

Ambiguity is therefore inherent in any public presentation. However, that the two Riel statues received such different receptions suggests that not all examples of commemoration are equally ambiguous. It is the nature of any symbol to suggest a range of interpretive pathways and to render others less attractive. Miguel Joyal’s statue suggests relatively few interpretive options; it is a statement as much as a symbol. Marcien Lemay’s figure is much more ambiguous. Ambiguity is certainly not an inherently negative quality. However, given the enduring social context of colonialism, any symbol that did not overtly oppose colonialism was suspected of collusion. In short, I contend in this paper that given the persistence of an interpretation of the Métis along colonial lines and the particular natures of the individual statues, the Métis leaders’ preference for Miguel Joyal’s rendering of Riel is both understandable and appropriate.

The controversy surrounding Marcien Lemay’s statue has been seen by some observers within the context of public art in Winnipeg. As Danielle Rice has observed, “public art ... has traditionally provided a forum for the airing of conflicting opinions about the nature and role of art.” [9] Some Manitobans objected to Lemay’s statue as they did not find it aesthetically appealing. For instance, Premier Schreyer’s office files contain a concise note dated 31 December 1971 asserting that the new “statue looks terrible. Poor Riel.” [10] All individuals are certainly entitled to their own opinions on matters of artistic taste. However, when Lemay’s statue is dismissed because of aesthetic objections, the historical and cultural significance of a monument to Louis Riel on the Manitoba Legislative Building grounds is often overlooked.

The historical significance is just as often disregarded by experienced artists or critics as by people who make no claim to expertise. Sculptor John Nugent has asserted that “the people in Western Canada are sculpturally illiterate.” [11] Bill Lobchuck, a local artist speaking on behalf of an organization known as the Art Collectors Club, echoed this sentiment some six years later: “For a city [Winnipeg] that is so culturally astute, its [sic] pretty awful and pretty ignorant as far as public art goes.” [12] Frequently, statements of this type are made as the removal of Lemay’s statue is being compared with controversies that have surrounded other works of public art in Winnipeg such as Justice and No 1 Northern. [13] In their tendency to interpret the controversy surrounding Lemay’s statue as simply another example of the general public’s artistic ignorance, these critics are effacing the singular significance of a statue of Louis Riel on the Manitoba Legislative Building grounds.

One of my primary objections to Frances Kaye’s article on the statue controversies in Manitoba and Saskatchewan is that her work is too firmly embedded in the language of artistic interpretation. Much of her article provides a useful historical survey that situates the statues within various symbolic systems. However, I am troubled by a few of Kaye’s phrases that could be interpreted as affirming the colonial assumption that Metis individuals are incapable of aesthetic judgements as sophisticated as those made by individuals educated in the European tradition. She falls just short of the level of analysis desired by Casey Nelson Blake. He believes that

Close examination of controversies over public art can recast the discussion about art and power by revealing the profound cultural fissures with respect to appropriate public activity and authority that lie at the heart of the most seemingly arbitrary assertions of artistic taste. [14]

Ultimately, I disagree with what seems to be Kaye’s fundamental premise: that these statues should be primarily understood as works of art. I believe that the controversy surrounding the Riel statues must be understood not in an artistic context, with rather with reference to the social and historical contexts that framed the events in question.

Grave of Louis Riel at the Cathedrale de St. Boniface.

Source: Robert Coutts

The nature of the social context for Metis people provided by late 1960s Winnipeg is preserved in documents concerning the preparation of an educational booklet designed for release shortly after the unveiling of Lemay’s statue. In a letter to the Honourable Peter Burtniak, Minister of Tourism, Recreation and Cultural Affairs, from Mary Elizabeth Bayer, Director of Cultural Development, dated 6 April 1971, Bayer stated that

The Manitoba Centennial Corporation “earmarked” funds to permit the publication of a pamphlet which would provide historical information about the founding of Manitoba in 1870, and the place of Louis Riel in the early history of that time. This pamphlet will be distributed to school children throughout the province, and will be made available to future visitors to the Legislative Building area. [15]

Bayer’s reference to the pamphlet as a source of information for visitors to the Legislative Building demonstrates the link that existed in the minds of the developers between the pamphlet and Lemay’s work—a link that is reinforced by the emblazoning of the pamphlet’s cover with a large illustration of the statue. The pamphlet’s text was originally written by Dr. Lionel Dorge, then of the University of Manitoba. The editing process to which this text was subject provides evidence that even as Riel was being memorialized, he was still being tagged with negative associations and conceptualized through colonial imagery.

Dorge recorded in writing his reaction to the changes recommended by the anonymous editor who reviewed his text. One of the most revealing disagreements centred on how Riel’s escape to the United States on the approach of Wolseley’s troops should be described. Dorge’s version, to which the pamphlet ultimately remained faithful, stated that “Riel and three of his supporters slipped away through the river gate of Fort Garry and sought refuge in the United States.” The editor recommended changing the passage to read “Riel and his associates slipped quietly through the back gate of Fort Garry and fled to a hideout in the United States.” Such a fundamental alteration in tone and implication garnered a heated response from Dorge:

“back gate” this of course is pejorative. It also shows ignorance of the inestimable importance of water transportation in Red River history. The “back” or south gate of the Fort was on the River. It was here that stood the flagstaff where Wolseley would fly the old Jack. Furthermore the “front” or stone or north gate was a much later feature of the Fort. It was added in the 1850s and gave access to the governor’s residence built at the same time when an extension to the Fort was considered necessary. It would seem that it was Wolseley who entered through the back gate ...

“quietly” why quietly? There was no one in the fort and again the word is suggestive of a thief in the night. Riel and his men had the common sense to leave before they were shot at like rabbits. There is little need to suggest anything but this. [16]

This fascinating exchange is of two-fold significance. First, the changes suggested by the editor seem designed to lessen the impact of Riel as a hero and to link him linguistically to other, less positive images. The Riel the editor seems to recognize is distinct from the man revered by the Métis people. That such negative images persist even in a text intended as part of a celebratory publication demonstrates the possibility of at once honouring and demeaning Riel. Second, though the alterations suggested by the editor may well have garnered a certain indignation from any author, it seems likely that there were other factors spurring Dorge’s response. The sarcasm evident in phrases such as “By the way, do the experts who revised the text have shares in the Hudson’s Bay Company? Sometimes the no doubt unavoidable repetition of the name sounds like a commercial” seems to hint at a depth of resentment beyond that merited solely by the editorial changes. [17] Such resentment might seem more reasonable if the editor’s version is understood as representative of an interpretation of the events of 1870 that was still prevalent in 1971. Dorge stated quite frankly that he felt that the “winning team tone” of the edited text was prevalent throughout Canadian society. [18]

Indeed, the propensity for subtle deprecation of Riel extended further than the pamphlet’s editing process and endured well beyond the year 1971. The media coverage of the Riel statue controversy illustrates as much. Most frequently, the concerns of Métis leaders were treated irreverently, framed in language that trivialized the issues and demeaned the intelligence of individuals who cared about them. For instance, in The Winnipeg Free Press of 17 May 1993, in an editorial titled “Manitoba’s Revised Statues,” the author asserted that “today’s Métis leaders find Riel’s sculptured nakedness demeaning. Why can Riel not have trousers on, like the others?” [19] By likening the Métis leaders’ concerns to a jealously childish desire for others’ possessions, the author not only mocked their concerns, but also revealed an ignorance of the historical context wherein nakedness was particularly offensive under Aboriginal and Catholic traditions. [20]

The Winnipeg Sun proved no more determined to provide articles that explained fully and fairly the concerns of Métis leaders. In a particularly ignominious article published while Jean Allard was camped out at Lemay’s statue, The Winnipeg Sun wondered if Allard’s dedication to the monument was due to a distinct physical similarity between man and statue. [21] Neither of Winnipeg’s daily newspapers viewed the controversy as worthy of further investigation. Through manipulation of narrative tone and failure to provide sufficient information, the concerns of the Métis were dismissed as trivial. It is thereby apparent that The Winnipeg Free Press and The Winnipeg Sun sought to minimize the subversive potential of individuals and organizations who opposed whatever appeared to be the current officially-sanctioned position regarding the commemoration of Riel on the Manitoba Legislative Building grounds.

Donna Graves has penned an insightful article regarding the creation of a monument to Joe Louis in Detroit and the varied but overwhelmingly negative public reaction that it garnered. The controversy surrounding the large suspended fist intended to commemorate a hero born of a marginalized community parallels that surrounding Lemay’s statue. The similarity supports an understanding of these events that not only emphasizes the specific situation of the Métis people in Winnipeg or the African-American people in Detroit, but also encourages the integration of their experiences into a broader context wherein similar colonial forces operate along various ethnic lines. In the conclusion to her article, Graves states that those who commissioned, created, and placed the monument in question “could not control, and did not consider, the ways in which this particular image recalled for many viewers a set of cultural and visual stereotypes borne of denigrating racial ideologies.” [22] In Winnipeg as in Detroit, what may have been good will on behalf of most involved either politically or artistically in the creation and erection of the first Riel statue was invalidated through inattention to social context. An extended fist could indicate the animal nature of African-American men; a contorted body might represent the fundamental weakness—or worse—Métis people. [23] The Métis leaders’ objections to Lemay’s statue should be understood as a rational and justified wariness on their part, as a persistent, if not articulated, understanding that any memorial has the potential to denigrate even as it preserves.

Concern could only have been heightened by the fact that Lemay’s statue was sufficiently ambiguous to allow drastic misinterpretation. For instance, a caption in The Winnipeg Guide of 16 July 1975 lamented that “After all the controversy during the centennial year in honour of Louis Riel, now he is left to rot and fall to pieces. Don’t we have any pride and respect. Pity poor Louis.” [24] Marcien Lemay responded with a letter dated 23 July 1975:

These statements are false and are obviously made by a person who knows absolutely nothing about the construction of this sculpture. The statue is not falling apart. The surface has not worn through to the steel metal supports. The mesh wire which shows through in certain areas was intentional and forms part of the surface texture. [25]

Lemay’s response clarifies the difficulty inherent to the interpretation of his work: the audience is not provided with sufficient information to ensure interpretations that correspond to the artist’s intentions. Without knowledge regarding construction, it is possible to believe the statue is disintegrating; without knowledge regarding the artist’s convictions, it may be possible to derive interpretations that differ quite substantially from the themes that inspired the artist. Such ambiguity is not inherently a deficiency, but becomes problematic in light of the social context from which the statue cannot be divorced.

Unfortunately, not all the damage to Lemay’s statue was of the type invented by a reporter’s misinterpretation. The monument was subject to extensive physical abuse while it stood between the Manitoba Legislative Building and the Assiniboine River. The statue had its genitalia smashed on numerous occasions, litter was often strewn around its base, and a life preserver, presumably stolen from a nearby bridge, was once placed around the statue’s neck. Stephen Greenblatt, in Learning to Curse, asserts that he finds signs of vandalism and alteration to possess resonance, to provide an “intimation of a larger community of voices and skills, an imagined ethnographic thickness.” [26] While Greenblatt may find the idea of vandalism intriguing, the Métis held quite a different view of the specific abuses to which Lemay’s statue was subject. In an article in the “Le Metis” of February 1977, Michele Cormier wrote:

“Let’s clean up Louis Riel” should be ou[r] motto.

But then, since the name Riel has been surrounded by so much garbage from people who misunderstand what he and his life’s work stand for, that I wonder if this little bit of material trash really harms his (white) “public” image.

Who will come to his rescue this time?” [27]

Lemay’s statue was subjected to an inordinate amount of vandalism, a fact that various people have attributed to its singular physical appearance. [28] If Greenblatt’s assertion that vandalism becomes part of a memorial is tenable, the damaged statue may have become a monument to the colonial assumptions that girded Riel’s “(white) “public” image”.

In response to Cormier’s pointed question, Métis leaders came to believe that Lemay’s statue was beyond rescue. In the 1991 Winnipeg Free Press “New Statue May Replace Defaced Riel”, Métis leader Yvon Dumont said that the vandalism “is an insult, but the statue as a whole is also an insult.” [29] Notably, Even as Cormier seems to be calling for the statue’s rescue, she makes observations akin to Dumont’s. By noting that the trash surrounding the statue was perhaps not the most pressing issue, she insinuates that it is the colonial assumptions animating Riel’s “(white) ‘public’ image” that must be confronted. By this point, Métis leaders would like to remove Lemay’s statue along with the trash. The salience of Greenblatt’s observations is demonstrated as, for prominent individuals within the Métis community at least, the statue and the vandalism had become indistinguishable.

Bust of Louis Rid located on the grounds of the Musee de St. Boniface.

Source: Robert Coutts

While the statue and the vandalism had become indistinguishable for some, the distinction between Riel as historical figure and Riel as artistic rendering had become blurred for others. Historical interpretations tend to become entrenched, to seem more credible each time they are retold, simply by virtue of repetition. In similar fashion, Lemay’s statue became naturalized over the twenty-year period between its erection and the public debate regarding its removal. This is evident in the comments written by members of the public in the notebooks Jean Allard made available during his two-week protest at the statue. The comments demonstrate a tendency on the part of many visitors to equate the statue and the man. In a plea typical of many, one supporter wrote “Don’t remove this statue. It represents a history that cannot be undone or erased.” This comment embodied the foremost fear of the Métis: that Lemay’s statue would legitimize an interpretation of Louis Riel that they condemned. While a supporter of Allard felt that Lemay’s statue was “here for a reason not a cause”, the Métis must have felt that such comments were proof that the statue had achieved its colonial purpose, had legitimized a vision of Riel to which they were fundamentally opposed. [30]

It was not only the Métis who condemned Lemay’s statue. Primarily in the years immediately before and after the statue was erected, there was limited but spirited debate from individuals who opposed any commemoration of Louis Riel for ethnic, national, or linguistic reasons. The files of Premier Edward Schreyer contain letters from people wanting to express their outrage at the erection of a statue dedicated to the memory of a man they still considered a traitor. A few went so far as to suggest that a statue to Thomas Scott should instead be erected. [31] One of the most virulent letters of opposition was sent to the editor of The Winnipeg Tribune. Stating that it was “with anger, revulsion and sheer disbelief that I read in the newspaper that approval had been given for the erection of a statue of that madman Louis Riel on the grounds of the Legislative Building,” the author threatens that

If this atrocity should be perpetrated, I hope someone will have a good supply of red or green paint handy. Should they require help, this former Manitoban will be delighted to come home for the “paint-in” (preferably just before the opening). It will be my Centennial project. [32]

Such deliberate threats place the vandalism to which the statue was subject in a different light: it no longer seems possible to blame the singular nature of the monument for all such behaviour. On the copy of the letter that I extracted from the Executive Council files is a typed note that follows the main text of the letter. I find this additional passage highly significant in its insinuation of a hierarchy that the author of the letter wants desperately to protect:

Derek: Can’t you do anything to stop them now? We managed to ignore these people for 10 years but obviously the new government was willing to listen I am more than a little disturbed!

For a historian, this brief note represents an interpretive challenge: it is unofficial, undated and unsigned. Yet perhaps it is the note’s very nature that is most revealing. The writer is obviously seeking to exploit personal connections, to perform the sort of machinations possible only for those secure in their positions of social privilege. Taken together, the letter to the editor and the added note become a powerful illustration of the alternatives still available to a colonial elite seeking to maintain its position. On a single page, we see evidence of clandestine efforts to prevent erection of Lemay’s statue and we hear of plans—however rhetorical—for a public display of the loathing directed toward Riel. In such a climate, when people were still so fervently seeking to oppose Riel through methods including both criminality and cronyism, Métis leaders were simply unable to tolerate a statue that offered a broad range of interpretive possibility. They desired a monument to Riel in the form of a visual statement that would directly contradict many of the readings that could be applied to Lemay’s statue.

Yet in the early 1970s, Métis leaders felt unable to staunchly and unwaveringly elucidate their desire. Angus Spence, President of the Manitoba Metis Federation, argued in a Winnipeg Tribune article of 12 January 1972 that the statue does credit “neither to Louis Riel nor to the Métis people of Manitoba.” However, Spence reluctantly acknowledges that “the government has at last done something to honor Riel’s contribution to Manitoba.” [33] The conciliatory tendency exhibited by Spence in 1972 is simply absent from the rhetoric of Yvon Dumont in 1989. Spence had been willing to accept what he could get; Dumont was determined to get what he could accept. A letter sent to the Honourable Gerald Ducharme illustrates that Métis leaders were no longer willing to tolerate a statue that they felt could potentially demean even as it commemorated. Dumont asserted that “We would rather have no recognition than to have Louis Riel recognized by a 2.5 million dollar park surrounding that existing disrespectful and negative statue.” In the same letter, Dumont threatens that

...when the development begins, or when the announcement is made regarding the Park, if there is no announcement as to when that shameful statue will be replaced by one of a “statesman” recognizing Louis Riel for the positive contribution to the development of Western Canada, then the Metis people of Manitoba will remove the statue promptly. [34]

Dumont’s rhetoric leaves no room for moderation: the statue is not potentially disrespectful and negative, it is disrespectful and negative. As the ambiguity of Lemay’s statue has already been established, Dumont’s unwillingness to allow for the possibility that it could be interpreted in ways that would honour Riel’s memory is perhaps indicative of how the Métis leadership understood their own situation at this point. Métis leaders, aware of their tenuous social position, would no longer prevaricate and could not tolerate ambiguity. It may have seemed all too likely that allowing for multiple interpretations would inevitably turn up some that were derogatory to the Métis.

Miguel loyal, the artist responsible for the second Riel statue, claims that the Métis leadership indeed sought in the second statue a clear and unmistakable rendering of their vision of Riel. Joyal’s Riel measures 8.74 meters, towering over Queen Victoria at the front of the building and even surpassing the Golden Boy in height. The Golden Boy is a symbolic rendering of Manitoba’s spirit and vitality that stands on top of the Manitoba Legislative Building. According to Joyal, the Métis leadership made a conscious decision to make Riel taller, believing that the founder of Manitoba should stand tallest on the Legislative Grounds. [35] In her article, Frances Kaye emphasized that educational limitations may have prohibited many Métis individuals from understanding Lemay’s rendering in the context of art history. A more accurate and complete explanation should include the recognition that Métis leaders may well have had no use for this context. While the Métis may not have understood or cared about the artistic antecedents of sculpture, they most definitely understood ways in which power can be represented in the visual realm.

That Métis leaders were cognizant of artistic symbolism is demonstrated again in the debate regarding where Joyal’s statue should be situated. In a letter to Gary Filmon, then Premier of Manitoba, dated 26 April 1993, Ernie Blais, then President of the Manitoba Metis Federation, seeks to secure a prominent location for Joyal’s statue:

Mr. Premier, at the time of our discussion with the Honourable Gerry Ducharme, Riel was still a traitor in the eyes of Canadians. Little did we imagine that within months, he would be recognized as a Canadian hero and founder of the Province of Manitoba. In the light of this recognition, Federally and Provincially, the Manitoba Metis Federation finds it appropriate to indeed place a new statue in a more prominent location, such as the front of the legislature. [36]

Louis Riel gravestre with local St. Boniface personalities, circa 1912. The monument was erected in 1891.

Source: La Societe historique de Saint-Boniface

While architect Etienne Gaboury may have strongly preferred the “symbolic bond between the Legislative Building (the white man’s heritage) and the Assiniboine River (the native’s heritage)” created by situating the monument to the rear of the building, such questions of artistic symmetry were overshadowed for Blais and his associates by their fundamental desire to create a clear statement of Riel as a figure worthy of respect and admiration. [37]

Eventually the Métis did agree to the situation of Joyal’s statue between the Assiniboine River and the Manitoba Legislative Building. However, their rhetoric indicates no change in their determination to obtain the most prestigious location for the statue. Instead, it was their view of what constituted this location that had changed. In a The Winnipeg Sun article titled “Dignified Louis”, Billy Jo Delaronde asserted on behalf of the Manitoba Metis Federation that “we believe the front of the building is facing the Assiniboine River. This was the first travel way for the province.” [38] Even as Métis leaders may have disagreed on how to symbolize the significance of their community and its most renowned member, all agreed that only the most prestigious location on the Legislative Grounds was appropriate for a statue of Louis Riel.

The complaint lobbed most frequently at Joyal’s statue is that it does not express the unique culture of the Métis people: as Terence Moore wrote in The Winnipeg Free Press, “if the Métis were London bank clerks, what is there to celebrate?” [39] This seemingly innocuous query is informed by assumptions not entirely dissimilar from those that animated some of the most virulent attacks on the legitimacy of Riel as hero. Certainly, Moore’s musing is not equivalent to the virulent ranting of the former Manitoban who threatened to deface Lemay’s statue. Nevertheless, implicit in both is a reticence to acknowledge the ability (in Moore’s case) or right (in the former Manitoban’s case) of the Métis to manage cultural symbols of power. In 1993, it was implied that the Métis might be making inappropriate choices about how to celebrate their heritage; in 1971, it was asserted that, within the Canadian cultural context, it was impossible to conceive of an appropriate celebration of Métis culture. Things had changed over the course of 22 years, but certain patterns of prejudice remain discernable throughout.

It is one of the many ironies of this series of events that it was in response to Lemay’s monument that Métis leaders sought to publicly articulate their vision of their history and culture, though they now look to Joyal’s statue for a representation of it. As Helene Lemay asserted during my visit to the Lemay home, it was Marcien Lemay’s statue that kept Riel and the Métis in the news for over twenty-five years. And it is one of the tragedies of the whole affair that Marcien Lemay, who so honestly sought to honour Riel in his rendering, was blamed for a series of events for which he was not wholly responsible. Miguel loyal believes that it was destiny that his statue of Riel should stand on the Manitoba Legislative Building grounds; as Marcien Lemay gazes at his maquettes and pages through his records, no such benevolent force is detected. [40]

Among the quotations on the walls surrounding Lemay’s rendering of Riel is this most famous Métis’ assertion that “I hope after my death my spirit will bring practical results.” The identity of the Métis community is unquestionably linked to Riel’s memory in a particularly palpable manner: In the context of their experiences, it becomes apparent that the analysis of artistic representations of this type cannot be divorced from the study of either historical interpretation or contemporary conditions. As a fairly straightforward representation, Joyal’s rendering neither challenges nor extends the limited range of representational options that were acceptable to the Métis. It is the range of interpretive options offered by Lemay’s statue—an interpretation of Riel that is inherently ambiguous but not inherently colonial—that made the work too great of a risk for the Métis community. Given the social context of Winnipeg between 1969 and 1996, Métis leaders’ unwillingness to tolerate ambiguity seems only prudent.

Métis leaders chose to remember Riel in a manner appropriate to their needs. Despite the particular importance of his memory to the Métis, it is certainly not the desire to animate their struggles with Riel’s spirit that distinguishes Métis culture. As Douglas Owram, Donald Swainson, and G. F. G. Stanley have argued, diverse groups and individuals have been doing the same for over 115 years. Riel’s presence in the Canadian historical landscape has attracted as much attention as that of his statues on the grounds of the Manitoba Legislative Building. Though Joyal’s monument may portray both how the Métis recall Riel and how they feel he should be remembered by all Canadians, the apparent simplicity of interpreting the statue belies the complexity of remembering the man. Whether Lemay’s statue was an effective illustration of the relentless tensions of Riel’s life, it certainly does seem appropriate as a memorial to the tensions that have persisted since his death.

1. Douglas Owram, “The Myth of Louis Riel,” Canadian Historical Review 63/3 (1982): 315-336.

2. Donald Swainson, “Rieliana and the Structure of Canadian History,” Journal of Popular Culture 14 (Fall 1980): 286-297.

3. George F. G. Stanley, “Un dernier mot sur Louis Riel: L’homme a plusieurs visages,” Riel et les Metis Canadiens, papers presented at a conference held by La Societe Historique de Saint-Boniface, 15-16 November, 1985. 86.

4. Frances Kaye, “Any Important Form: Louis Riel in Sculpture,” Prairie Forum 22 1 (Spring 1997), 107.

5. Catherine L. Mattas, “Whose Hero? Images of Louis Riel in Contemporary Art and Metis Nationhood” (MA Thesis, Concordia University, 1998).

6. Marsh, James H. , ed. The Canadian Encyclopaedia (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1988) , s.v. “Metis,” by Jennifer S. H. Brown.

7. Ann Stoler, “Sexual Affronts and Racial Frontiers: European Identities and the Cultural Politics of Exclusion in Colonial Southeast Asia,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 34 3 (July 1992) : 521.

8. John Bodnar, Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century (Princeton University Press, 1992) : 16.

9. Danielle Rice, “The ‘Rocky’ Dilemma: Museums, Monuments, and Popular Culture in the Postmodern Era” in Critical Issues in Public Art: Context, Content, and Controversy, eds. Harriet F. Senie and Sally Webster (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1992) , 235.

10. Premier’s Office Files, EC 0016, Provincial Archives of Manitoba [PAM] Accession GR 1664, File 918 Part 1, Historic Sites and Monuments, 122/98.

11. Winnipeg Free Press, 4 August 1991.

12. Winnipeg Sun, 12 April 1997.

13. A further example of this is W. P. Thompson’s “Public Sculpture in Winnipeg: A Selective Tale of Outdoor Woe,” Border Crossings: A Quarterly Magazine of the Arts from Manitoba 5 2 (March 1986): 10-12.

14. Letter obtained from the Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage, and Citizenship, as a result of a request under The Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

15. Centre du Patrimoine, Fonds Dorge, Lionel, Box 2, File 44.

16. Centre du Patrimoine, Fonds Dorge, Lionel, Box 2, File 44.

17. Centre du Patrimoine, Fonds Dorge, Lionel, Box 2, File 44.

18. Centre du Patrimoine, Fonds Dorge, Lionel, Box 2, File 44.

19. The Winnipeg Free Press (Winnipeg) , 17 May 1993.

20. Issue of nudity in an Aboriginal context is addressed by Catherine L. Mattes, “Whose Hero? Images of Louis Riel in Contemporary Art and Metis Nationhood” (MA Thesis, Concordia University, 1998) , 82-83. Issue of nudity in a Catholic context is addressed by Frances Kaye, “Any Important Form: Louis Riel in Sculpture,” Prairie Forum 22 1 (Spring 1997) :108.

21. Winnipeg Sun, 15 July 1994.

24. “Pity Poor Louis” in The Winnipeg Guide 3 27 (Winnipeg), 16 July1975.

25. PAM, Louis Riel Monument, Government Services File GS 0123, GR 173, M-9-6-8.

26. Greenblatt, Stephen J. Learning to Curse: Essays in Early Modern Culture (New York: Routledge, 1990), 171-172.

27. Le Metis (Winnipeg), 2 February 1977.

28. PAM, Louis Riel Monument, Government Services file GS 0123, GR 173, M-9-6-8.

29. Winnipeg Free Press, 24 October 1991.

30. All the passages I have quoted come from the books kept by Jean Allard for public comment during his two-week protest at the Manitoba Legislative Building. I was very generously allowed to study the photocopies of these books that are the private property of Marcien and Helene Lemay.

31. Document obtained from Manitoba Executive Council, as a result of a request under The Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. PAM, Accession GR 1664, File 918 Part II Historic Sites and Monuments.

32. Document obtained from Manitoba Executive Council, as a result of a request under The Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. PAM, Accession GR 1664, File 918 Part II Historic Sites and Monuments.

33. Winnipeg Tribune, 12 January 1972.

34. Letter obtained from Manitoba Urban Affairs, as a result of a request under The Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

35. Interview with Miguel Joyal, conducted by the author at Joyal’s residence, 16 December 1998.

36. Letter obtained from Manitoba Executive Council (Premier’s Office Files), as a result of a request under The Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

37. Letter obtained from Manitoba Executive Council (Premier’s Office Files), as a result of a request under The Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

39. Winnipeg Free Press, 17 May 1993.

40. The personal observations contained in this paragraph stem from personal interviews conducted by the author with Marcien and Helene Lemay (conducted at their residence, 18 December 1998) and Miguel Joyal (conducted at his residence, 16 December 1998).

Page revised: 26 February 2022