Search | Image Archive | Reference | Communities | POV | Lesson Plans | Credits

Even before the establishment of a Public Health Department in Winnipeg in 1900, it was known that infant mortality was abnormally high. When figures on the infant death rate were first reported by the City Health Department in 1908, they showed that one in seven (14.3%) infants died in their first year (excluding still births). This number rose steadily to a high of nearly one of five (19.9%) in 1912.

Even before the establishment of a Public Health Department in Winnipeg in 1900, it was known that infant mortality was abnormally high. When figures on the infant death rate were first reported by the City Health Department in 1908, they showed that one in seven (14.3%) infants died in their first year (excluding still births). This number rose steadily to a high of nearly one of five (19.9%) in 1912.

City government took its first steps to tackle the high infant mortality rate in 1910. Since most deaths were attributed to gastro-intestinal diseases, which were in turn attributed to contaminated milk, most efforts concentrated on educating mothers about the safe feeding of infants and providing a safe milk supply. That year, the city established the City Free Dispensary, which distributed "modified (pasteurized) milk" free of charge to those most at risk.

Despite these efforts, infant mortality continued to rise. The health department recognized that the problem was not negligence so much as poverty, and that "economic conditions are responsible for a large proportion of the infantile mortality." Notwithstanding, education continued to be the focus, and the city's medical officer explained in his Annual Report of 1911, "We feel that no matter how bad the economic conditions, a very large number of children's lives could be saved if mothers only knew proper infant care... It is along educational lines that the most important work in preventing infantile mortality is to be done."

In the second decade of the century, the Health Department became more aggressive in its educational campaigns. In 1910, it began publishing a monthly health bulletin, and it composed and distrib uted a series of pamphlets on hygiene and household management in several languages. It also engaged public health institutions, most notably the Margaret Scott Nursing Mission, to do home visitation and provide instructions on proper infant care. It also developed a series of illustrated lectures that were presented at the All Peoples' Mission in the North End.

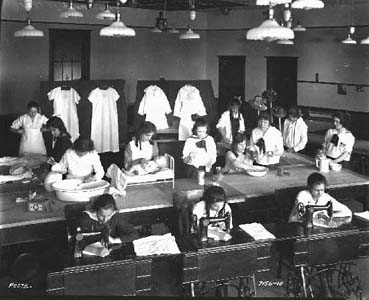

One of the programs that was developed in conjunction with the Winnipeg School Division was the Little Mother Movement. Under these auspices, trained nurses were sent into the schools to provide instruction on hygiene and child care to girls of school age. The Little Mother program offered several advantages over other methods of health education. Language and tradition were obstacles to the communication of ideas about preventive health care to many families. By targeting a campaign at young girls, it was intended that they take the information home to their mothers.

By choosing an essentially captive group of school children, the Health Department was able to reach a much larger audience than with its public lectures and brochures. Language and literacy beca,e less of a barrier. Children were more likely to be persuaded of the unsuitability of traditional infant-care practises, which were seen as causal factors in the high death rate among immigrant children. Furthermore, much of the message in the Little Mothers' classes had to do as much with socializing a younger generation to accept Anglo-Canadian ideas of the family as about public health.

Page revised: 29 August 2009