Search | Image Archive | Reference | Communities | POV | Lesson Plans | Credits

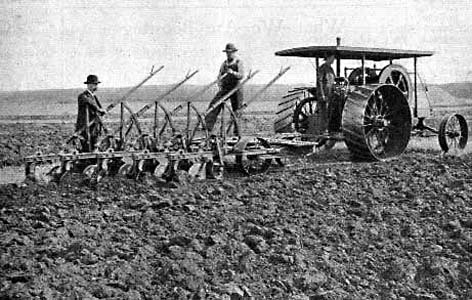

While the invention of the steam tractor revolutionised prairie agriculture, steam was not without its limitations. Steam engines were complicated and delicate machines which required a great deal of maintenance. The process of building-up steam and then letting it down again was time-consuming and limited the amount of time that could be spent in the field each day. It also consumed huge amounts of fuel. Steam operations were dependent on a steady supply of clean water, and often two or three teams of watermen were required to haul water over great distances. Finally the machines were very heavy, and when they were used for ploughing, they could become mired in soft soil.

While the invention of the steam tractor revolutionised prairie agriculture, steam was not without its limitations. Steam engines were complicated and delicate machines which required a great deal of maintenance. The process of building-up steam and then letting it down again was time-consuming and limited the amount of time that could be spent in the field each day. It also consumed huge amounts of fuel. Steam operations were dependent on a steady supply of clean water, and often two or three teams of watermen were required to haul water over great distances. Finally the machines were very heavy, and when they were used for ploughing, they could become mired in soft soil.

By the second decade of the century, farmers had a real alternative to steam. Internal combustion engines, powered by either kerosene or gasoline, appeared in about 1905. They delivered more horsepower for their weight and did not require the delicate and time-consuming process of building steam. Their greatest asset was in their fuel. Petrol and kerosene were less bulky to haul than coal, wood or straw, and with no boiler, there was no need to haul large volumes of water over large distances. Early gas engines were bulky, expensive and unreliable, but by 1912, more new machines used gas than steam. By the end of the First World War, gas had replaced steam in most mechanized operations. It should be noted, though, that this new technology was available only to relatively affluent farmers, and most relied on horses for many of their operations for another two decades. It was not until 1941 that more then half of all prairie farms possessed tractors.

The coming of the internal combustion engine meant only small changes on the threshing crew at first. The engine required only one operator, eliminating the need for firemen and tankmen, but the thresher remained the same, and a large crew was still required to haul bundles and feed the machine. Their greatest advantage was in hours worked. Without the lengthy firing cycles, the gas engines were able to operate from dawn to dusk with only brief interruptions for re-fuelling and maintenance.

By 1920, a real revolution was afoot. With these lighter and less expensive machines, farmers became increasingly self-sufficient in ploughing and harvesting. With a small tractor and a small portable threshing unit, a farmer could do most of the fieldwork and harvesting with only two or three hired hands. In this way, the farmer could avoid the expense of a custom thresher and a dozen or more employees. Furthermore, farmers could harvest when they saw fit, not when the operator was in the area, significantly reducing the risk of losing a crop to frost.

Page revised: 29 August 2009