The Story Told by Maps

Maps are the best way we have to visually grasp the physical reality of

settlement patterns for a time when photographic record is sparse to

non-existent. Other records will give us statistics, names and numbers;

but it is through maps that we get the big picture.

This section documents the available maps and traces the evolution of

the communities in the Wawanesa area.

View the Complete Map

Archive....

The

Settlement Era

If, in 1858, one were to follow the course Souris Rivers upstream from

its mouth near Wawanesa, one would encounter no farms, no roads, no

villages, and few, if any, humans. In fact, in 1858 an expedition led

by Henry Youle Hind did just that. Explorers in those days were

especially interested in rivers and would follow them anywhere.

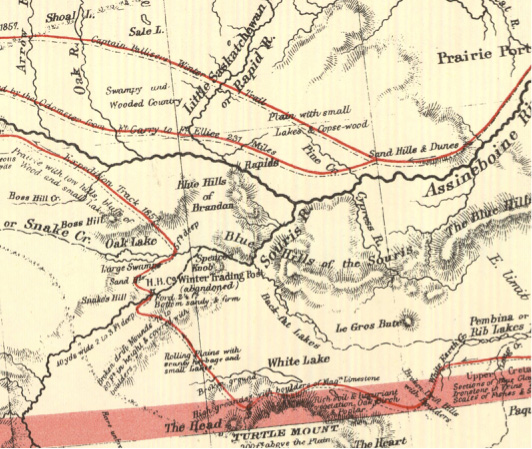

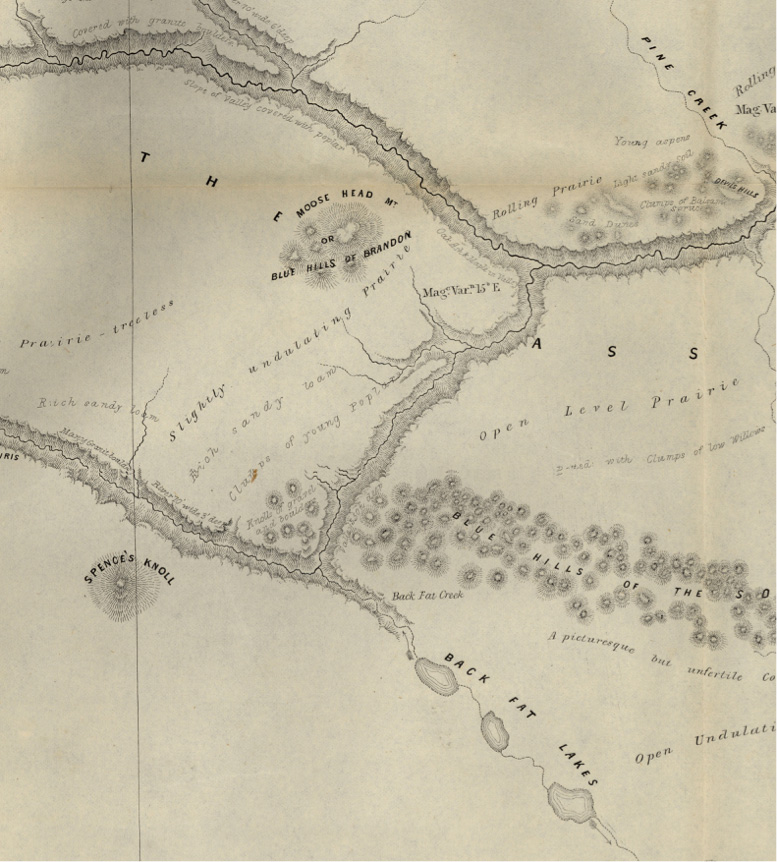

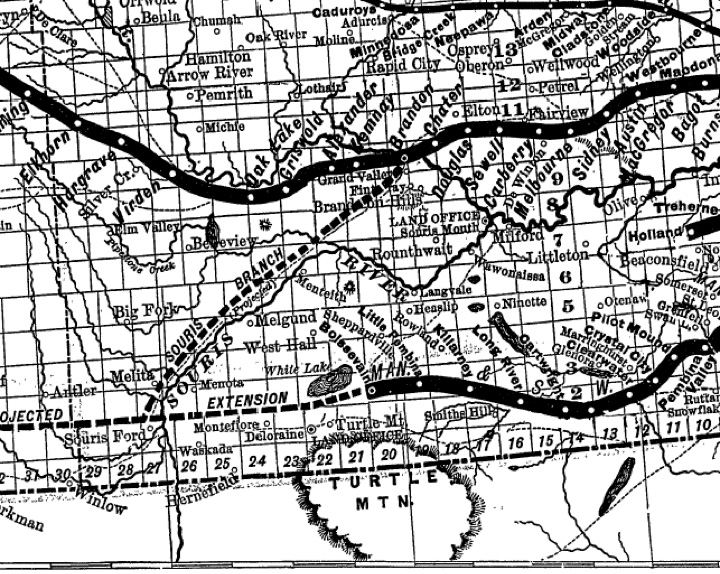

Map 1. Hind 1858

His map shows landmarks we still recognize today, notably, the “Blue

Hills of Brandon” and the “Blue Hills of The Souris”. It would be a

lonely walk. You might pass a small band of Assiniboine on the lookout

for the rapidly disappearing buffalo or other game. You might meet a

traveler, straying from the established trail, also on the hunt.

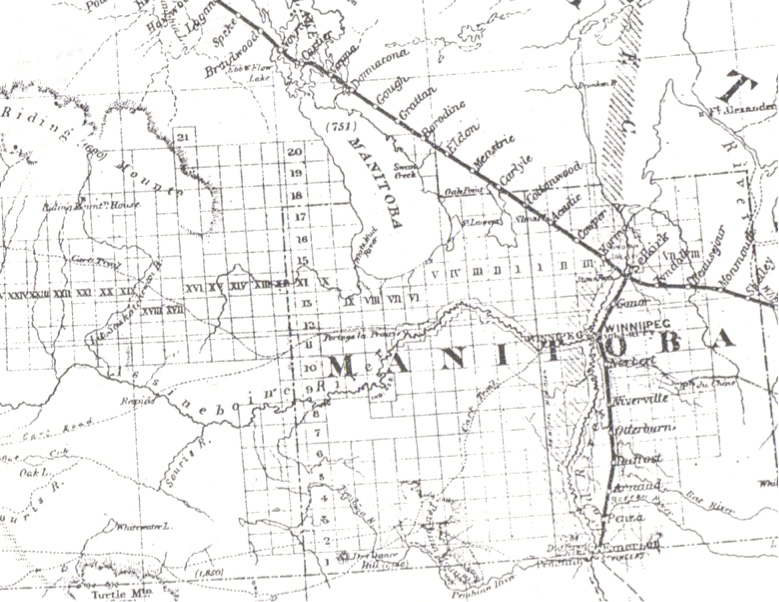

Map 2. Dawson 1859

Dawson’s map from 1859 contains a bit more detail concerning the

landforms. Compare to a modern map and note some of the waterways have

had name changes.

Jump ahead over a decade and look at this map prepared by a Mr. Laurie

in 1870.

Map 3. Laurie, 1870

Not much had changed. It looks like he basically copied Mr. Hind’s work

– secure in the knowledge that nothing had changed. Not only were there

no settlements, but settlements weren’t even anticipated in the near

future. It is true that the Federal government under John A. MacDonald

were determined to colonize the west, having just acquired a huge

portion of it from the Hudson Bay Company, and to that end were

planning a trans-continental railway that would link eastern Canada

with British Columbia. Convention wisdom said they were nuts. Today we

say they were visionaries.

All bets were that the railway, if it ever got off of the ground, would

follow the northern route leaving the southern plains as they were.

The choice of this route was based on exhaustive research by two

extensive exploratory expeditions. John Palliser, an Irish gentleman

adventurer, who had already traveled widely in the American West, was

selected by the Royal Geographical Society and the Imperial Government

to explore the area between Lakes Superior and the Rockies and report

on everything from plant species to possible travel routes. After a

two-year field trip he concluded that the only good land in the area

lay in a belt along the North Saskatchewan. In fact the vast area

comprising the southern third of Saskatchewan and Alberta, now called

Palliser’s Triangle, was deemed thoroughly unsuited to agriculture.

Another expedition, sponsored by Canada and lead By Henry Youle Hind, a

geology professor from Toronto, came to similar conclusions. There was,

apparently, no real future for the southern prairies. Normally,

railways are built where the customers are. In this case the railways

came before the customers, so it was a case of deciding where the

customers would end up.

Map 5. Fleming Survey 1877

A more detailed look at the northern route – Fleming 1877. They had

even gone so far as naming the stops.

By the late 1870’s opinions had begun to change and a more southerly

route was being considered for at least the Manitoba portion of the

line.

The decision, or more significantly, its approval by the government,

may also have rested on a few other foundations. Politically it was

advisable to located closer to the American border to preempt possible

competition from an American line and to keep a firm grip on the

territory at a time when many prominent Americans viewed the annexation

of the west by the US as not only desirable, but inevitable. On a more

practical note we were probably seeing the beginnings of the C.P.R’s

policy of avoiding high prices and land speculation by bypassing

expected routes and established communities. They truly were doing the

unexpected in this case. Additionally the southern route was shorter

and would be (they thought!) less expensive to build. Some have

speculated Mr. Hill saw the possibility of some arrangement whereby his

other venture the Great Northern in the U.S. would benefit from some

arrangements with the C.P.R.

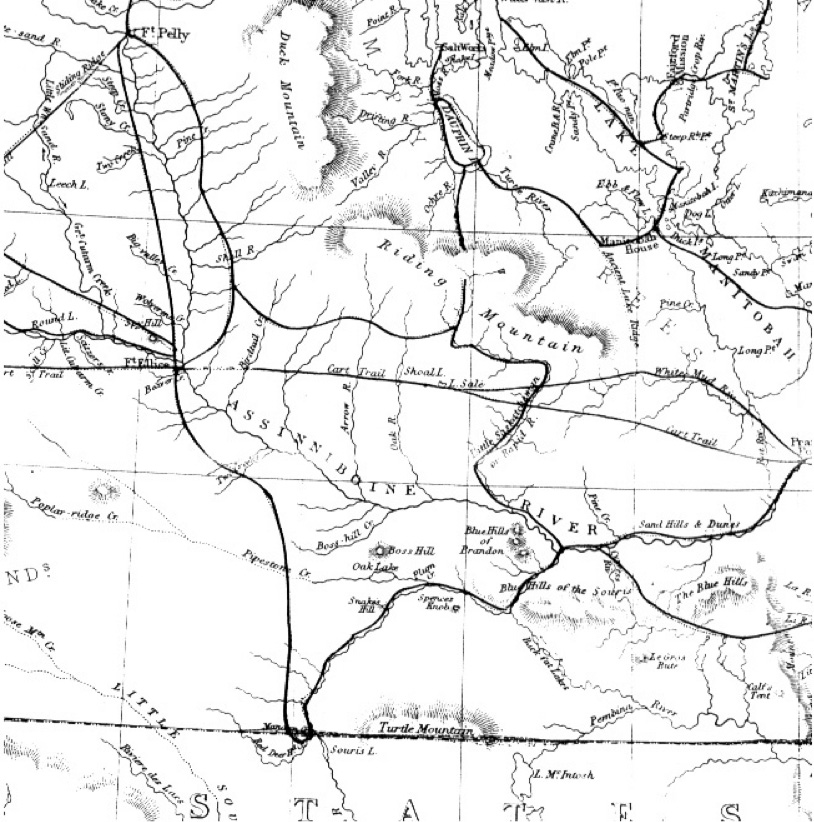

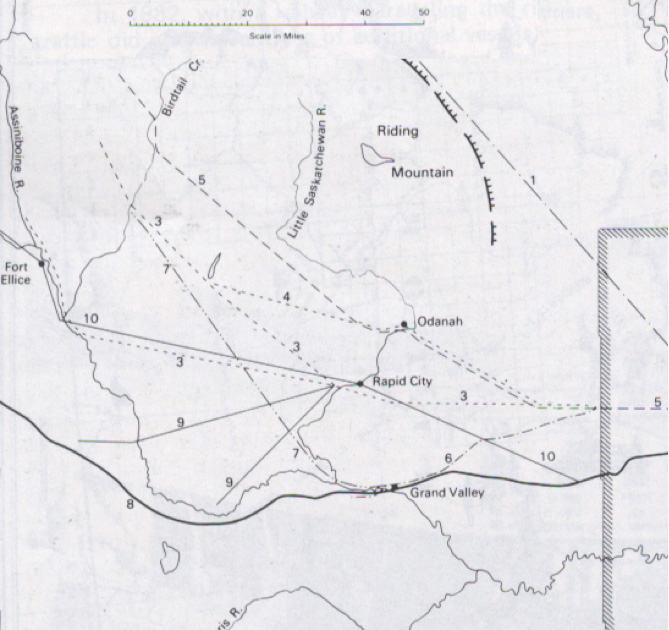

Map 6. Proposed Railway Lines in Western Manitoba

So things had changed, and by 1880 a rush of settlement was

anticipated. A transcontinental railway was becoming more than just

rumours and a pipe dream, and numerous proposals had surfaced for rail

connections lines throughout Manitoba. Note that none of these

proposals seemed to consider the possibility of even branch lines into

the Manitoba southwest.

1. Original 1872 proposal for the main C.P.R. At that time the belief

was that the Saskatchewan River Valley was the best place for

settlement, and the line was to proceed northwest from the crossing at

Selkirk. The first surveyed proposal, not shown on this map, actually

went through the narrows of lake Manitoba instead of along the eastern

edge of Riding mountain. Both ended up near Swan River before heading

west.

Numbers 3 - 7 were routes examined between 1877 and 1880

Route number 7 is from an idea Sanford Fleming, the Dominion Surveyor

had while visiting what would become the Brandon area before he

actually fully planned this southern line, which in 1880 was expected

to be the final decision. The idea was to proceed eastward from

Winnipeg and to veer northwest from Portage, with Edmonton and the

Yellowhead Pass the ultimate pathway to the west coast. Had that

happened the whole course of settlement history would have been

drastically altered for the R.M. of Daly and the rest of Western

Manitoba.

But what did happened, was that, at the last minute, with the rails

being set down almost as far as Portage a decision was made to follow a

more southerly route. Route #8 is where the track went in 1881-82 and

the rest is history. That spurred the next big speculative frenzy –

predicting where branch lines would go.

Number 9 shows just one early example – the proposal for the Souris and

Rocky Mountain Railway planned in1880. Dozens of ideas would follow,

with only a handful ever coming into being.

By 1880 this largely unpopulated area was slowly developing the first

tentative forays into agriculture with the noticeable beginnings of

towns seen at Rapid City, Minnedosa (Tanner’s Crossing), Millford (near

the confluence of the Souris and Assiniboine Rivers), and Grand Valley

(a few kilometers east of Brandon). These locations are mentioned

in the George Wyatt’s 1881 “Guide for Settlers”, which includes a list

of post offices and charts with destinations for both steamboat and

stagecoaches, while the site that would later become Brandon was an

undeveloped homestead.

Map 7. Stage and Mail Routes

This map, showing stagecoach and mail service in the early 1880’s show

the links. The locations mark Post Offices, not necessarily towns.

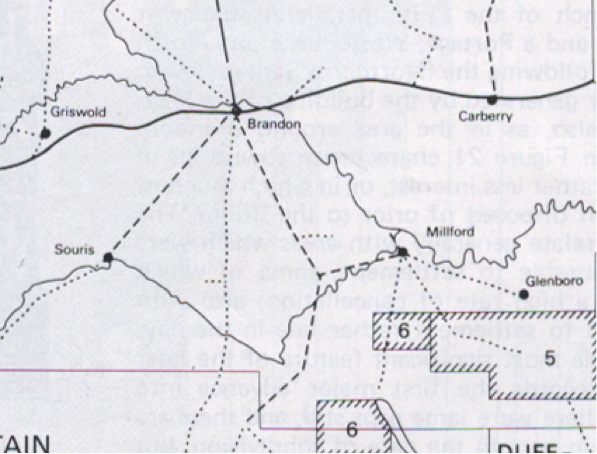

This 1886 map show the Wawanesa area still waiting (patiently) for a

rail link.

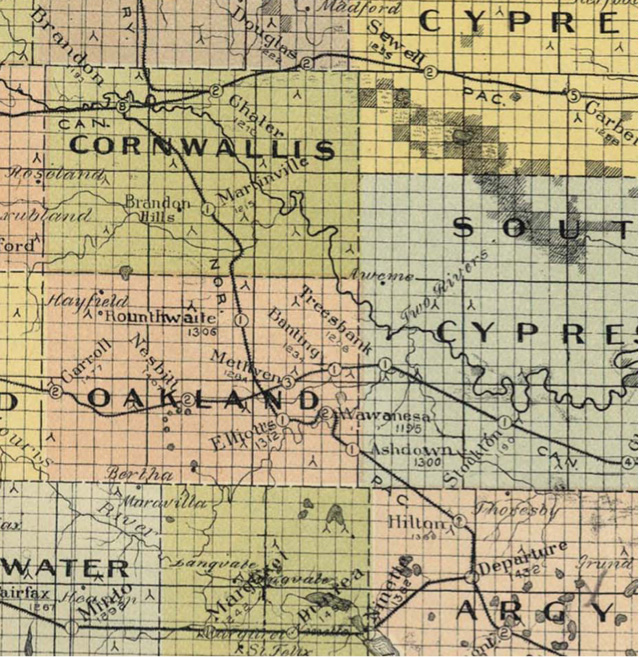

Map 9. Provincial Government Map, 1900

By 1900 two rail lines served the region and the pattern of stations

and villages was altered to fit those lines. Souris City and Millford

have disappeared. Wawanesa, Treesbank and Nesbitt have been created.

So that‘s the way things looked at the beginning of the 19th century as

the settlers who had taken the risks, made the journeys, worked to

establish farms, and established schools and churches; waited

(patiently) for long promised railway lines that would push both

economic and social development to the next level.

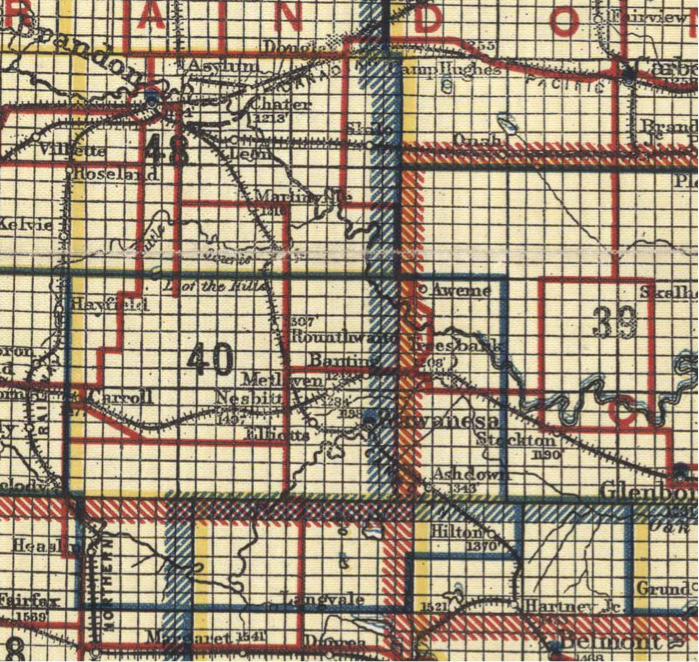

Map 10. Manitoba in 1915

By 1915 rail lines had been extended so that most farmers had less than

10km to haul grain to an elevator.

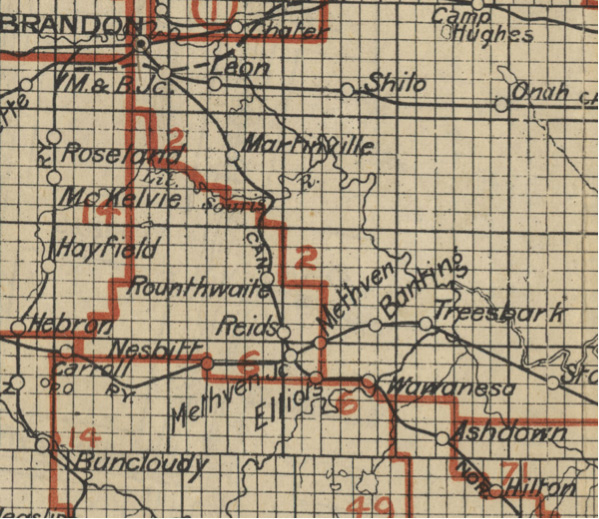

Map 11. Manitoba Highways 1924

This highway map from 1924 shows the network of roads being developed,

as the automobile became our first choice in transportation.

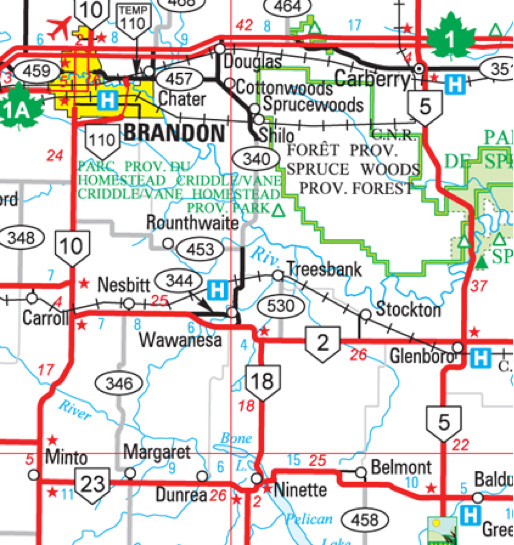

Map 12. Manitoba Road Map 2010

The 2010 Highways Map shows which villages and place names have

remained.

What the map doesn’t show is that other placed names, recalling sites

and building long gone, live on in the form of cairns (Chesley

Church), road signs (Gregory Mill Rd.), and of course in our

excellent local history: “Sipiweske”.

|