| Index |

|

5. Real Towns Have Mills

The

period from 1881 and 1882, known as the “Manitoba Boom”, saw

intense speculation in land sale – especially in town lots. Everyone

knew that the population of rural western Manitoba was going to

explode. Towns would be built, businesses established, and money would

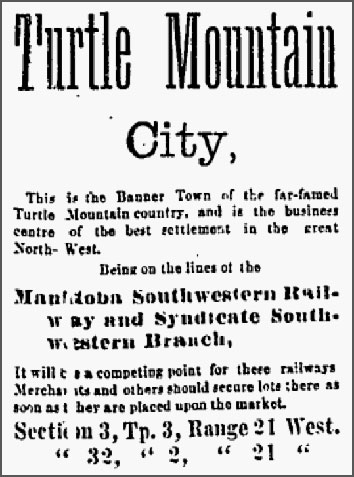

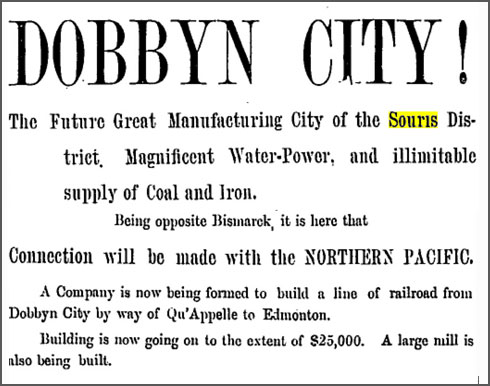

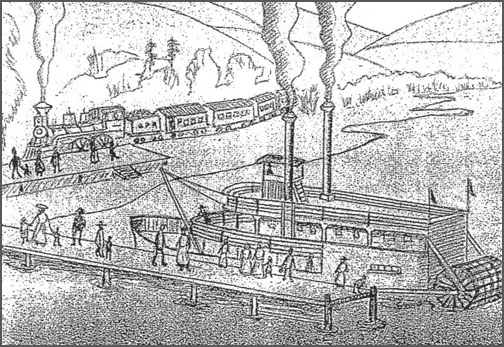

be made.The problem was that nobody was sure where all these new towns would be located. It all depended on where the railway lines would run, and where the railway company would decide to put a station. Although some railway surveys had been undertaken and some lines had been planned, no one knew where the stations would be. So some enterprising landowners decided that a piece of land they owned might just be a good spot for a town Speculating in town lots was a bit like participating in a gold rush. You stake a claim and hope it pays. The difference was that in the case of the gold rush, there was at least a tiny chance that there would be actual gold. In the case of town lots it should have been apparent to a discerning investor that the railway decided where towns would be and they generally avoided places where land prices were inflated. And even after a survey, the railway routinely changed its mind as to the exact location of a line, sometimes at the last minute. So where thousands would willingly rush off in search of gold based on rumours and wild tales, town lots had to be aggressively marketed. Exaggerations and outright lies were the tools of that trade. To sell the lots the promoter had to assure prospective buyers that the rail line was a sure thing. An ad for Turtle Mountain City, just a bit to the northwest of Wakopa, made that claim of not one, but two railways. And although it was on the general path of the actual Manitoba Southwestern Railway, when that railway did arrive, it missed Turtle Mountain City by a few miles.  Winnipeg Times, Dec. 20, 1881  Winnipeg Times, March 9, 1882 Dobbyn City, near where Melita is today, promised to be an even bigger deal. Railways would connect it to the whole continent! Beyond that, aside from making a claim about the supply of coal and iron, it promised water power and, like most speculative cities it promised a “large mill”. But the best “Boom Town”, story, without doubt, goes to Moberly, literally, located on a swamp, on the southwestern tip of Whitewater Lake, and promoted far and wide via newspaper ads and pamphlets, as a sort of seaside resort town with a town square, a steamboat landing and scenic hills in the distance.  It is hard to recognize Whitewater Lake from this perspective. The claims were beyond

extravagant. Indeed the whole episode was so

well-known and so outrageous, that the word Moberly became a sort of

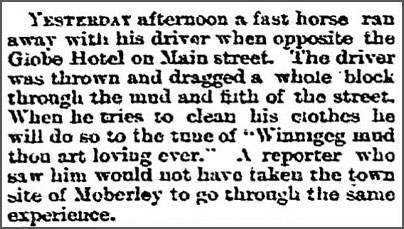

catch word for the boom town experience. The following newspaper story

is one of several that allude to Moberly in this way.

Winnipeg Daily Sun, April 5, 1882 Despite the rather obvious fraud (Mr. B.B. Johnson of Emerson, one of the promoters, was the only instance I have discovered of someone actually being charged and convicted of fraud is such a matter), even newspaper reporters accepted some of the wild claims and in general, were caught up in the whole thing. The claims made in the following story could easily have been set to rest by checking with any local resident.  Winnipeg Daily Sun, Dec 23, 1881 There never was a building of any sort at Moberly, and the “nearest Mill” was indeed much closer than Clearwater. The mill at Wakopa in fact, had been up and running for some time. Wakopa was a real town, rather than a paper town. And the fact that it had a mill is quite important. The primary purpose of pioneer agricultural settlements, like those around Turtle Mountain, was to grow grain. The problem was that getting a crop to market was a long haul. Having a gristmill nearby, where one could at least exchange wheat for flour was a crucial advantage in making a homestead sustainable until a railway would arrive. A sawmill was also an early priority as there was no convenient way to import lumber. The development of the grain business began in Wakopa long before the railway was built through Boissevain and Killarney. In 1878 Matthew Harrison built saw and flour mills in the new village. The rumbling mill was powered by a water wheel on the banks of Long River. George Bennett, who freighted from Emerson to Wakopa with a team of oxen, Buck and Bright, a fast team of oxen. He brought the first gristmill stones to Wakopa imported from France. These stones are very heavy and are in various places. One is in the Cairn at Wakopa and one is in the museum in Boissevain. This historic industry was the first in Turtle Mountain municipality. A water wheel also powered the whining blades of the family sawmill. To accommodate the settlers who brought their wheat from afar by oxen to be ground into flour, the family built a boarding house and large livery barn. In 1881 Bill Harrison joined his brother, and in 1882 another brother George came west and joined the company. These businesses, along with B.B. Lariviere’s Store and Stopping Place established Wakopa as an important place. People came to Wakopa, bringing grain to be ground into flour, or buying lumber at the sawmill. Meals were served at the Harrison home, at La Riviere’s, and at Mrs. J. Melville’s boarding house.  Winnipeg Daily Sun, April 28, 1884 The coming of the railway to Killarney doomed this busy centre. The brothers disassembled their mill and built Killarney's first grain elevator. Later they built a gristmill at Holmfield that would serve the area for many decades. On the second floor of that historic building one can still see the rough cut 2 by 6’s that were sawn at the old Wakopa for the Harrison’s next enterprise. And a visitor to the Turtle Mountain Flywheel Clun Museum in Killarney can see the machinery from the original Wakopa gristmill on display. |