Brickyards

Some time ago, while visiting at

one of Hartney’s fine brick homes, I

was shown a portion of the wall that clearly displayed the paw print of

a cat. The owner explained that the bricks came from a small local

brickyard, and, yes, the owner’s cat must have roamed the facility

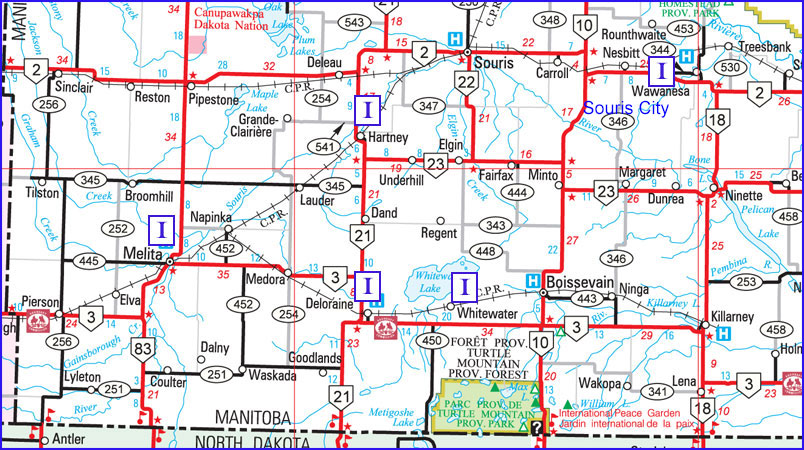

during the early stages of the brick-making process. Only in Hartney – cat’s paw bricks! Limited edition. Manitoba is geologically blessed with thousands of clay deposits, hundreds of which have been exploited over the past 150 years for brick manufacture. The “Golden Age” of this aspect of Manitoba’s building history was from 1880 to 1912. There were about 60 major clay sites and about 175 brick manufacturing plants that provided the billions of bricks that were required for Manitoba’s major building boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The details of industrial operations were not often covered in local newspapers and so it is only possible to provide a sense of typical operations. The work was hard and the days were long. The pay was modest, about $2 a day, but it was steady, at least for the duration of the season, usually from May (when the frost left) till August or September. Even small yards had up-to-date technologies such as steam-power. A typical operation featured the large covered drying sheds that new bricks were laid into. It was the final stage of the brick-making operation that usually distinguished a major from a minor yard: whether the brick was fired in a scove or beehive kiln. The scove kiln. Most likely used in most operations in the southwest corner, was a less sophisticated technology, but one that was still effective enough to produce good quality brick. Burnings lasted about seven to eight days, and when the outer shell of bricks on a scove kiln was removed, workers discarded the disfigured and discoloured bricks nearer the fire source. The first settlers often built a sod hut for those first few years. Logs were hard to find on the open prairie, but those living along the Souris River or in the vicinity of Turtle Mountain might start with a log house. If logs were available someone might set up a sawmill, but otherwise milled lumber was expensive and involved some difficult hauling. Settlers who arrived with a bit of cash in hand might opt to bring in building supplies, but many had to wait for that first frame dwelling. Brick was desirable as a building material, but was even more expensive to ship than milled lumber, so it was some time before brick buildings became popular. What helped that process along was the fact that some of those new settlers came with some experience making bricks, and they kept an eye out for deposits of clay that would serve that purpose. Locations  The first bricks made in the southwest corner were likely produced by at Souris City, the village that preceded Wawanesa. A brickyard was established there by Mssrs. Freek and Coupland. It produced a low quality type of brick used for the lining of wells. Whitewater / Deloraine Perhaps the earliest brickyard in the Turtle Mountain region was located a near Whitewater, on the N.W. quarter of. 17-3-21. In 1894 the factory was sold to W. R. David and the brick machine moved to Deloraine next to the Racetrack. Hartney The most extensive brick-making operations in the southwest corner were located in Hartney and involved three enterprises. The most important practitioner was William Kirkland. At the height of his ten years of brick-making, in 1913, he was firing bricks for the new Saskatchewan Legislative Building. Harry Payne and George Sackville each had moderately successful operations in the 1890’s The Melita Brick Co. In 1905 Mr. John Dobbyn (80 years of age) discovered a red brick clay just west of the river and south of today's #3 highway. He purchased the land (31-3-26) and ordered a modern brick making plant. The Melita Brick and Tile Co. was formed in April 1905. Conclusion Virtually all brickyards in southwestern Manitoba ceased operations before or during the First World War. In some cases brickyards functioned until the deposit of clay ran out, in other cases competition and declining demand were factors. By 1910 most productive land had been taken and the building boom was over. |