Manitoba Pageant, Winter 1968, Volume 13, Number 2

|

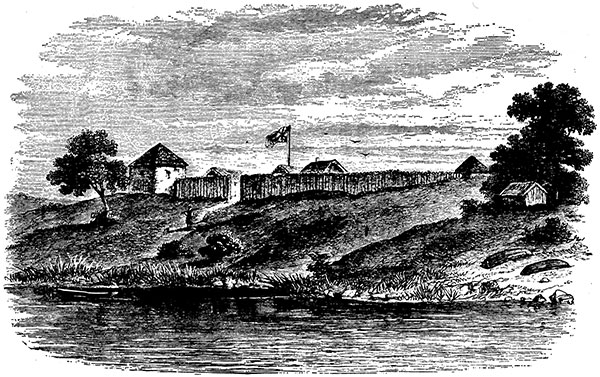

Fort Douglas (1817) from the pencil sketch by Lord Selkirk.

Source: Lord Selkirk’s Colonists, The Romantic Settlement of the Pioneers of Manitoba by George Bryce, 1910, London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co., p. 112.

The second party to arrive at The Forks (1812), while not a large one, was the first party of real settlers and had a few women and children in it. They left Stornaway on 24 June 1812, had a good crossing, and arrived at York Factory on 28 August. After a week at the Bay they left in eleven boats and three canoes, reaching The Forks on 27 October, a little over six weeks after the working party.

In the meantime the Governor had been busy preparing for the settlers, and by the time they arrived he realized that with the shortage of supplies at The Forks it would be impossible for so many to winter there. Pembina would be the best place for a winter encampment. This place had been for many years the winter headquarters of the buffalo hunters, the buffalo coming from the western plains every fall to winter on the high lands of the coteau.

The fur trade companies each had a fort of sorts at the junction of the Red and Pembina Rivers, the Hudson’s Bay on the east bank of the Red River, the Northwesters on the north bank of the Pembina. Soon after the arrival of the settlers at The Forks they left for Pembina and while there the young men went out on the buffalo hunts, the old men and the women and children remaining in Fort Daer, which had been built for them. Early in the spring, as soon as the river was clear of ice, they returned to the settlement, anxious to get their homes built, crops and gardens planted.

The third party (1813-14) was mostly from Sutherlandshire. Conditions had become very bad in that part of Scotland during the past few years, one single sheep farm having displaced one hundred tenant farmers. The Countess of Sutherland had forcibly cleared her land, burning homes, killing or running off the cattle when tenants did not move out fast enough to suit her. In desperation the tenantry had been forced into the small coastal villages, and hearing of their plight Lord Selkirk determined to help as many as possible emigrate to Red River.

The third party of settlers (1813) were aboard the Prince of Wales; the HBC men were aboard the Eddystone. The above sketch (after Peter Rindisbacher) shows these two vessels abreast Captain Parry’s squadron in Hudson Bay, 15 July 1821.

Over seven hundred applications were received but by the time all arrangements were completed it was found that only one hundred could be taken, this was mainly on account of shortage of ships, the Northwesters having leased all available ships in the southern ports in order to block Lord Selkirk’s plans. Those chosen gathered at Stromness, settlers from the Parish of Kildonan and Helmsdale, a few from the Islands, Company men from the Orkneys and Ireland, and after a number of last minute delays set sail on 27 June, the settlers in the Prince of Wales, the Company men in the Eddystone, both ships under convoy of the Sloop-of-War Brazen.

It was a difficult trip from the start, the captain was arrogant, the officers most inefficient, the ship was under-manned and very badly crowded, they ran into bad weather and added to all this ship’s fever broke out on board the Prince of Wales, said to be the first time on board a Company ship. The surgeon, LaSerre, a Guernsey man, and a great favorite with the settlers, was one of the first to succumb, leaving the settlers without trained medical aid. Many stories have been told of the stout hearted folk who turned in and nursed the settlers, not only on board but afterwards at Churchill, where it was weeks before all were clear of the fever, several dying after arrival there.

On arrival at Churchill the ship’s captain insisted on landing the settlers although their transportation was to York Factory, where accommodation and supplies awaited them. It has never been clearly explained why Captain Turner did this. Whether it was panic on his part or just pure cussedness is still a mystery, but landed they were with only a part of their luggage. After this the captain immediately set sail only to run on a sand bar a few miles from port. The ship was refloated and Governor Auld, who had arrived from York, tried to get him to take the settlers there, but he delayed so long at Churchill that it was too late in the season to go to York Factory, so off he sailed for England.

This was the beginning of the winter (1813-14) spent at Churchill of which much has been told and written. A camp was established fifteen miles up the river at a fresh water creek and here at Colony Creek, as they named it, the settlers, many still weak from fever, built log houses and prepared as best they could for the coming winter. While landing, a large boatload of baggage was lost when the boat was swamped, leaving the settlers short of clothing and other supplies including much needed drugs.

After a cold, dreary winter on short rations and in cramped quarters, twenty-one men and twenty women, with guides and hunters, left Colony Creek for York Factory. They travelled in single file on snowshoes, drew their supplies on rough sleds, camped at nightfall, moved on at daybreak, a gunshot rousing them at 3:00 a.m. to have breakfast and hit the trail. Halfway down the line of march was the piper and other stalwarts bringing up the rear gathered in the stragglers and helped the weary to keep up.

In the same order as they left Colony Creek, we are told, they arrived at York Factory, having met with no serious mishap enroute. Archibald McDonald, who was in charge of the party, when reporting to Lord Selkirk tells of the progress made by the young women on snowshoes: “I must do them justice in the great reformation they made in science before they came to their journey’s end.” After a few days spent at York Factory in resting and preparing for their inland trip they left on 23 May and arrived at The Forks on 21 June, extremely good time for the trip. The balance of the party reached The Forks in August.

Red River, 1817 - In this vicinity Lord Selkirk called his settlers together, and here he set aside land for church and school.

Source: A Journal of the Reverend John West, 1827

The present St. John’s Cathedral and churchyard. The above photo from the Thomas Burns collection was taken in 1914.

This fall (1814) it was decided that the settlers would remain at The Forks, and it was during the winter that the North West Company at Fort Gibraltar went all out to be friendly and by this false friendship persuaded many of the settlers to desert and break their contracts with Lord Selkirk. By spring it was apparent to the Governor that nothing short of the total destruction of the settlement would satisfy the Norwesters.

There were rumors of them bringing in Indians to attack the settlement (there are letters on file to prove this) and the enmity between Miles Macdonell and Duncan Cameron had reached fever pitch. Finally an agreement was reached whereby Cameron agreed that if Miles Macdonell would surrender to him and go to Montreal as his prisoner the Norwesters would leave the settlers and the settlement unharmed. After some consideration, feeling that it was the only solution in the circumstances, Miles Macdonell surrendered and was taken to Montreal with the spring brigade.

On arrival he was released on bail and never brought to trial. However, when the North West brigade was ready to leave the settlement with the Governor and one hundred and forty deserting settlers, a party of Norwesters under the command of Alexander “Yellowhead” McDonnel, accompanied by Cuthbert Grant, attacked the settlement. Homes were burned, crops trampled, and the few remaining loyal settlers, thirteen families of about sixty persons, were allowed to gather together a few belongings and set out for Jack River, there to await the arrival of the next party from Scotland.

This party (1815), the largest to date, was, under the command of Robert Semple who held for the time the dual appointment as Governor of Assiniboia for the Hudson’s Bay Company and Governor of the Settlement for Lord Selkirk. This party sailed on 17 June, made a good trip to York Factory, arriving there on 18 August and at The Forks on 3 November.

Lord Selkirk had come to Montreal in 1815 with the hope of coming to terms with the North West Company and to arrange for a military force of some kind for the settlement. He also planned to visit Red River. In the meantime, Colin Robertson, who had been acting as Lord Selkirk’s agent, spent some time in Montreal gathering news from the settlement as well as information from the North West Company’s headquarters. He left Montreal with the Athabaska brigade, the first Hudson’s Bay brigade to go west by the North West Company’s southern route.

On his arrival at Lake Winnipeg, Robertson learned from friendly Indians that the settlement had been destroyed and that the majority of the settlers had deserted to the Norwesters and had gone to Canada with them. The few remaining settlers were at jack River. Leaving the brigade Robertson went north to Jack River, gathered up the settlers and brought them back to The Forks where they harvested the crops and rebuilt a few houses before Semple’s party arrived.

When Colin Robertson and the settlers arrived back at The Forks they found that “Young John Macleod,” the Company man in charge when the Northwesters attacked, together with three companions, had managed to hold out in the blacksmith shop with the aid of a small cannon and shot made of cut chain. After several days and several attempts to rush the blacksmith shop, the Northwesters left. Then John Macleod and his friends, with the help of some freemen, salvaged what crops they could. Later they cut timber for new buildings, rebuilt the Governor’s House and several other buildings in a new location to the south side of the point. They called it Fort Douglas instead of Colony Fort as it was before.

The fur trade companies each had a fort of sorts at the junction of the Red and Pembina rivers, the Hudson’s Bay on the east bank of the Red, the Northwesters on the north bank of the Pembina. The above sketch (after Peter Rindisbacher - 1822) shows the Nor’Westers’ Pembina Post (r) and Fort Daer (l) where the second party of settlers stayed during the winter of 1812-13.

Shortly after the arrival of Semple’s party the settlers once more set out for Pembina. A few of the younger men remained behind to cut timber for buildings and to prepare the land for seeding in the spring. In June 1816 the settlers were back at The Forks. New houses appeared along the river lots, but there was an air of uneasiness as more and more rumors of Indian raids persisted.

From the coming of the first settlers Chief Peguis had been a true friend. He taught them the ways of the country, hunting, trapping, fishing, and even brought in meat, fish, and wild fruits when rations were short. He steadfastly refused to have anything to do with the Norwesters and their plans for destroying the settlement. The settlers felt that things might have been much worse after Seven Oaks if Peguis and his men had not come up from their camp to stand by in case they were needed.

In the late afternoon of 19 June Cuthbert Grant’s party was sighted from the tower at Fort Douglas. They were approaching from the south-west at an angle that would bring them into the settlement some distance below Fort Douglas, Governor Semple therefore sent word for all the settlers to come into the fort. Then he gathered together a number of Company men and a few settlers and marched out along the Settlement Road parallel to the route taken by Grant. About half a mile from the fort, seeing the number of men Grant had, Semple sent back to the fort for reinforcements and for the one and only cannon. Their other cannon had been taken over to Fort Gibraltar by the deserting settlers in the previous year.

On sighting Semple’s party Grant split his men into two detachments. One rode towards the river ahead of Semple’s men, the other coming in behind cut off Semple’s party from any help from the fort. The usual story at this point is that Boucher, a Frenchman, rode towards Semple, waving his gun and shouting as he came abreast of him. Semple grabbed the gun and pulled Boucher part way out of his saddle. In the scuffle the gun went off, its discharge being greeted by a fusillade from Grant’s men. By this time Semple’s men, surrounded and cut off from the fort, were being slowly forced towards the river.

It was soon over. Semple’s men had only one round of ammunition each. Governor Semple was wounded in the initial skirmish and later was killed by a renegade Indian, the only Indian in Grant’s party, although all his men were dressed and painted to appear like Indians. Grant lost only one man; Semple lost twenty men. Their horribly mutilated bodies remained on the open plain until the next day when Peguis and several of the settlers went to Grant and demanded that they be allowed to remove the bodies for proper burial.

Grant made camp at Frog Plain, where Kildonan Presbyterian Church now stands. Then he sent word to Alexander McDonald, who Governor Semple had left in charge of Fort Douglas, that he would take over the fort that evening and if one shot was fired it would be a signal to his men to destroy every man, woman and child. Alexander McDonald at first refused but realizing later that they were at Grant’s mercy he sent word that the fort would be surrendered. Grant took an inventory of everything in the fort and gave McDonald a receipt which he signed as a clerk of the North West Company. A couple of days later the settlers were allowed to gather together their personal belongings, (any that had been left), and start once more for Jack River. Many left the settlement with the idea of returning to Scotland.

Norway House, 1925

Source: Hudson’s Bay Company Archives

After the Battle of Seven Oaks the survivors were allowed to gather together their personal belongings and to start for Jack River (now Gunisao-variant of Cree “kinuseo” - jackfish or pike). 1. Oxford House, 1801 - “Embarked two canoes with six men and a good assortment of trading goods to go Jack Lake and erect a house ...” (Journal of William Sinclair, HBC). 2. Jack River, 10 July 1816 - “Got to the North Wagen’s Place in the morning.” (Journal of Alexander McDonald). 3. Shortly after the above entry, Jack River Post (where Norwegians were building a ‘wagen’ road to York) was moved to Norway Point, later to Playgreen Lake, being known at both places as Norway House.

We know from North West records that Cuthbert Grant received his orders direct from the headquarters at Fort William to gather together as many of his followers as possible from around Qu’Appelle and to attack the settlement and destroy it. A party of Northwesters were to meet Grant at the settlement to take charge, but as Grant arrived on the 19th and the party of officers on the 22nd one may draw their own conclusions as to the validity of the original arrangements for the rendezvous.

As the settlers were northbound they were met by this North West party. Their baggage was searched for letters and records. John Bourke, who was wounded at Seven Oaks, and John Pritchard were taken prisoners. Then the settlers were allowed to proceed.

The next spring when Lord Selkirk was at Fort William he found lists of the men who took part in the massacre at Seven Oaks as well as lists of the “presents” they received for their part in the attack. He also found thirty bales of HBC furs from the Qu’Appelle District.

It was during this time, while in Montreal, that Lord Selkirk arranged for four officers and one hundred and forty other ranks of the recently disbanded DuMeurons and de Wattville Regiments to go to Red River as settlers. They would receive land with the understanding that they would serve in a military capacity if their services were needed. This arrangement for “settler-soldiers” to go to the settlement thwarted the policy of the Canadian government which refused to permit a military force to be taken into what they still called “The Indian Country.”

With a small party in express canoes Miles Macdonell had started for Red River to tell the settlers that Lord Selkirk was on his way, bringing with him the Du Meurons, as they were called. When he reached the Lake of the Woods he was told of the destruction of the settlement and that the Northwesters were holding the fort. He immediately turned back and met Lord Selkirk and his party at the Soo. On hearing of Seven Oaks, Lord Selkirk threw caution and secrecy aside and set sail immediately for Fort William. On arrival there he seized the fort, arrested the North-wester officers, and released Lajimonier and Pritchard who had been taken prisoners while returning to Red River from Montreal.

As soon as overland travel was practicable Miles Macdonell, Captain D’Orsenne and twenty men, with two small cannon mounted on sleds, started for the settlement by way of Lac la Pluie (Rainy Lake) and Fort Daer (Pembina). They captured several North West forts enroute. Coming into the settlement from the south, they circled west on the Assiniboine, stopped long enough to cut trees for scaling ladders, and on 10 January, in bright moonlight, seized Fort Douglas without a shot being fired.

The Battle of Seven Oaks - a simulated portrayal by C. W. Jefferys

Source: Picture Gallery of Canadian History, Vol. II.

At once Miles Macdonell arranged for a party to go to Jack River to tell the settlers about the retaking of their fort and that Lord Selkirk was on his way to the settlement. A few of the settlers, returning with the Company men, came in over the frozen lake to The Forks in order to rebuilt the houses and plant crops before the spring break-up. The remaining settlers would return as soon as lake and river were clear of ice. All this happened between 10 January and break-up. We who know something of the tempestuous nature of Lake Winnipeg can imagine a little of what these trips were like.

Lord Selkirk reached The Forks in June and while there he called the settlers together. He granted land to twenty-four who had made improvements on their farms before Seven Oaks and who had lost so much in the conflict. Other settlers received land at five shillings per acre, payment to be made in produce to the Hudson’s Bay Company, as previously arranged. He also made plans for roads, bridges, mills, and an experimental farm, and set aside land for church and school, promising as well that a Gaelic speaking minister of the Presbyterian faith would be sent to them.

It was at this time that he asked Alexander McBeth, on whose land the meeting was held, to choose land farther down the river so that the land previously granted to him might be used for the church. There had already been a number of burials there, including several of the men killed at Seven Oaks. He also asked that the church be called Kildonan after the parish in Scotland from whence so many of the settlers had come. (This is the property where St. John’s Cathedral (Anglican) and St. John’s Park are located.)

Shortly after leaving the settlement in mid-September Lord Selkirk was served with a warrant to appear in Montreal to answer charges brought against him by the North West Company. From this time until his death he spent most of his huge fortune in a vain attempt to reach a settlement with the Northwesters. However, in the Canadian courts of that day he had little chance of winning a just verdict as they were entirely dominated by the North West Company and their powerful friends.

Lord Selkirk, now a very sick man, returned to Scotland late in 1819 and shortly thereafter went to the south of France in the hope of regaining his health. There he died in April 1820. In the same year it was ironical that the two great rival companies, under pressure from the British Government, were reluctantly forced to move toward a coalition. The union came to head on 21 March 1821; the license for the new monopoly being granted by parliament on 2 July 1821. Fifteen years after Lord Selkirk’s death his estate sold back to the Hudson’s Bay Company all that part of the original Selkirk Grant which had not been deeded to the settlers.

“To hand over to them the sovereignty, as it may be called, of an extensive country where we had the prospect of doing so much good, is a transaction to which I cannot easily reconcile myself, and I would reckon it immoral as well as a disgrace if it were done from any view of pecuniary advantage ... With respect to giving up the settlement or selling it to the North West Company, that is entirely out of the question ... I know of no consideration that would induce me to abandon it.

I ground this resolution, not only on the principle of supporting the settlers whom I have already sent to the place, but also because I consider my character at stake upon the success of the undertaking, and upon proving that it was neither a wild or visionary scheme nor a cloak to cover sordid plans of aggression, charges which would be left in too ambiguous a state if I were to abandon the settlement at its present stage, and above all if I were to sell it to its enemies.”

Lord Selkirk, in a letter from

France, April 1820.

Assiniboia, the Selkirk Grant, showing the locations of Jack River House and Fort Daer in relation to Fort Douglas. The location of “Fort” Pembina (Post) is incorrectly shown. The dot representing its location should be above the Pembina River at its northwest junction with the Red. The Hudson’s Bay post opposite the mouth of the Pembinais shown as “Old Fort”.

Page revised: 29 September 2016