Manitoba Pageant, Spring 1968, Volume 13, Number 3

|

No more large parties were brought out to Red River, although a few settlers who were mostly members of families already there came out to the settlement from time to time.

With the exception of two winters spent at The Forks, the settlers were forced to winter at Pembina, from where they returned each spring to Red River to plant what crops they could, often not having sufficient seed for their needs. Year after year they faced the long trek to and from Pembina, each winter facing cold and storms on short rations, but always hoping that some day they would be allowed to establish their homes in peace at Red River.

Their route from The Forks to Pembina followed roughly the course of Red River. They camped at night where the river bank was high, then pushed on again at daybreak, perhaps in the midst of an early snowstorm, a quick spring thaw, or an unseasonable thunderstorm.

Most of us who know Highway 75 between Winnipeg and the International Border will find it hard to imagine what the settlers endured on these trips. Looking back we can only marvel at their endurance and perseverance. Highway 75, officially named the Lord Selkirk Highway by the Government of Manitoba in 1962 (the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the first party) is a fitting memorial to those hardy Scots who trecked bock and forth along this route to finally secure their settlement at Red River in peace and prosperity.

It was not until after the union of the two fur trade companies in 1821 that the settlers were able to stay in their homes at The Forks without fear of attack by the Nor'Westers. From that time forward they were able to develop their farms and bring more land under cultivation, to improve their implements and hence their methods of husbandry. But it was slow, hard work.

They were still an isolated settlement and their major base of supply, York Factory on Hudson Bay, was seven hundred miles away. Only one or two ships arrived there each summer from England, and goods and supplies which were consigned to Red River had to be transferred to York Boats at York Factory for the long and arduous inland trip up the Hayes-Nelson chain to Lake Winnipeg and thence by Red River to The Forks.

However, once freighting was established between The Forks and St. Paul (Minnesota) a new source of supply for incoming products as well as a market for surplus goods and produce from Red River was established. This much closer source of supply for household goods and commodities, for tools, utensils, and implements helped to make life easier than it was in the very early days when all goods and supplies had to be ordered a year in advance from England. The settlers' clothing no longer consisted wholly of home-woven materials. Bolts of cloth, finished dresswear, suits, and bits of finery - laces and ribbons, as well as spices and staples could now be obtained from St. Paul within a few weeks of the time the order left Red River by a cart brigade.

One of Lord Selkirk's plans for the settlement was an experimental farm. The first, called the Colony Farm, was on the Point a short distance from Fort Douglas. When the DuMeurons arrived this was done away with so that their twenty acre lots could be laid out there, each with river frontage.

The next farm, Hayfield, was about halfway between Fort Douglas and Fort Garry. It was put under the management of William Laidlaw who was brought out from Scotland to develop this enterprise. Although a great deal of money was spent on stock and equipment, this farm was not a success. It was abandoned in 1824.

Another experimental farm was established in St. James on the Assiniboine River (opposite Fort Osborne Barracks). Chief Factor James McMillan was brought in from the fur trade to manage this farm, but after a few years operation it was closed. The next and last experimental farm, located on the Hudson's Bay Flats, [1] lasted all of ten years. Then it too was closed.

After the union of the two fur trade companies a great number of officers and senior men in the west were former Nor'Westers. These men had been in the country for years and they were the logical ones to carry on the fur trade. It was unfortunate for the settlers, however, that these men were the same ones who had done so much to keep the Hudson's Bay Company and the settlers out of the country. The reports of this period, deeply tinged with old antagonisms and bitterness, are now understandably misleading. Only in the last few years, since miscellaneous papers of the North West Company have been brought to light, has the whole story come into the open.

"Most of the homes had an outside oven in which bannock and later bread and pies were baked. These were used long after the modern stoves came into the settlement ..."

By the middle 1830s the settlers had built up large herds of cattle and sheep, and because of the plentiful supply of butter, cheese, and wool which they yielded, life in kitchen and parlor was made easier. The surplus above home requirements could be used in trade with the Company for imported foods and other household commodities. In the early years fresh meat was a rarity, although there was usually plenty of fish, game and waterfowl. Large quantities of fish were dried for winter use. During more than one winter season, however, the settlers had to depend for sustenance on the take of the buffalo hunt. [2]

Whitefish, goldeyes, sturgeon, and catfish were caught in large numbers. Sturgeon or catfish oil was burned in small lamps or cruisies; [3] it was sprinkled on fleece to soften the fibres, was worked into hides to make them soft and pliable, and later on was used for oiling gears in mills and farm implements. In the very early days buffalo tallow was the only fat available for cooking and baking. There was no preserving as we know it today, but wild berries [4] were eaten fresh from the bush or dried for use in autumn and winter.

Tea, coffee, rice, raisins, and currants could be purchased from the Hudson's Bay Company pretty much according to the purchaser's means. Sugar was always in lump - huge lumps that had to be broken down and crushed before using. Soap could be purchased but it was very expensive. Most housewives made their own soap once or twice a year. Soft soap was made for immediate use, and hard soap, hardened by adding salt, was cut into bars and stored until required during the winter.

From the earliest days each settler had his own vegetable garden which produced a goodly supply of potatoes, turnips, carrots, onions, peas, and beans.

As soon as freighting started between St. Paul and The Forks, coal oil was brought in and used for lighting lamps. [5] It was very expensive and hard to store. The settlers therefore used candles by choice long after the more convenient coal oil lamps were available. Generally one lamp in each home was kept for use on the Sabbath or for when the minister called. The making of candles was a long and tedious job, so the whole household usually turned in and helped, working industriously for several days until a year's supply had been turned from the molds.

Meal was supplied to the settlers by the Hudson's Bay Company until they had their own mills for grinding grain. The first mill, built at Fort Douglas, was sold to Robert Logan who agreed at the time of purchase to grind all the grain which the settlers brought him for a charge of 10%. This meant that for every 100 pounds of flour milled, the settler left 10 pounds with the miller. There was no yeast in the settlement until a brewery was built in West St. Paul in the middle 1850s. Before that time bannock and oat cakes were eaten instead of yeast breads.

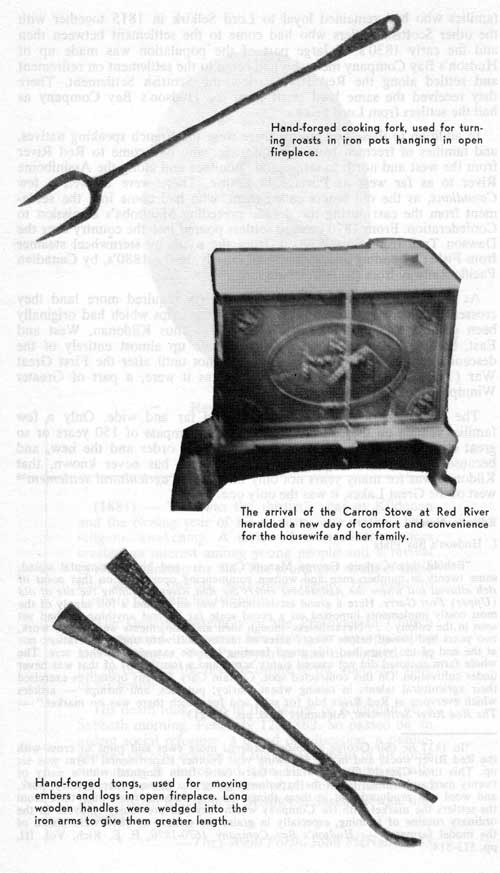

At first open fireplaces in the kitchen were used for heating the home and cooking food. Most homes had an outside clay oven as well in which bannock and later bread and pies were baked. These ovens were used long after the modern cook stove came to the settlement as many of the older women preferred them. Carron stoves, [6] manufactured in Scotland, and brought to the settlement by the Hudson's Bay Company, were in general use. These oblong box stoves were packed flat for shipment, a most convenient way to bring them in over the tortuous Hayes-Nelson route with its many rapids and portages.

Kildonan Presbyterian Church (circa 1882) - "The church is to be erected on a piece of land long desecrated by the Indians (a site of their dog feasts), and by the Sabbath evening sports of some who bore a better name but whose works were not so much better than theirs." - From a letter of John Black, 1851.

Even after the Pembina trips had ended there were other troubles to be faced. Dry seasons were followed by wet ones, crops were .destroyed by grasshoppers, [7] early frosts nipped vegetables and grain, and prairie fires which came roaring in from the plains cut down stands of hay. Fortunately, however, apart from the loss of hay, the prairie fires at Red River caused no other serious damage.

In 1826 the whole country was flooded when the Red River rose nine feet in the first 24 hours of its flood stage. Settlers and Company men took refuge on the high ridge above the Assiniboine River west of Omand's Creek. Others went north to Stony Mountain or east to Birds Hill.

In 1852 another flood [8] struck and although it did not rise as high as in 1826 the property damage was greater simply because there were more buildings and livestock in the settlement than there had been twenty-six years before. Again the settlers went to the three high spots until the water receded, and they did not return to the settlement to plant their crops and rebuild their homes until early in June.

There were other floods and seasons of high water, but the floods of 1826 and 1852 were the really destructive ones. It may be noted that the old homes in Kildonan were built a long way from the river. This comes about, of course, from lessons learned in the flood years, and we who have grown up along the river still speak of the lower bank and the flood bank.

Life in the settlement was not all hard work. As far back as the harsh winters at Pembina we read of evenings spent in dancing and singing, of skating and games on the ice. Later at Red River there were horse races on the ice. There were gay times at weddings and at New Year, and in all the festivities the old songs of Scotland, passed along from one generation to another, were sung with glee. The jigs and reels, danced to the lilt of the pipes or the sweep of the fiddler's bow, were always happy events.

From the time of the arrival of the Reverend John West, the Hudson's Bay chaplain, in 1820, there was a mission church in the settlement. As mentioned previously, the settlers had been promised a Gaelic speaking minister of their own faith. But for reasons too many and diverse to go into here it was not until the coming of the Reverend John Black [9] in 1851 that they had their own minister and church. Prior to Black's arrival the settlers worshipped at St. John's mission, and they were most appreciative of the many kindnesses of the Anglican clergy.

With the arrival of the Reverend John Black, the settlers built their church on land deeded to them by the Hudson's Bay Company in lieu of the property which had originally been granted to them by Lord Selkirk in 1817. The original site had been used from the first by the Anglican Mission which became St. John's Cathedral and by the church school which became St. John's College.

All the material for the building of Kildonan Church was lost in the flood of 1852. However, the church which was built in the following year has been in continuous use ever since. Old Kildonan therefore bears the distinction of being the oldest Presbyterian Church west of the Great Lakes.

The settlers took little part in the rebellion of 1869-70, and they were severely criticized in some quarters for their stand. For three generations they had lived on the best of terms with their neighbors, the French and the metis, who dwelt for the most part on the St. Boniface side of the Red River or west along the Assiniboine.

The metis went hunting and fishing wherever they wanted to; they made their homes where fancy took them, and it was therefore only natural that the idea of newcomers moving into the territory to take over large parcels of land should fill them with dismay. It is a sad fact that many of those coming into the Red River country at the time from Canada and the United States had but one idea - the country was theirs for the taking, and in their hunger for land they showed great contempt for the rights of the native born.

The Scottish settlers felt that the metis had their just grievances, but the Scots were intensely loyal to the Crown and thus would have nothing to do with any movement which, in their opinion, smacked of treason. [10] They sympathized to a degree with the aims of the metis but regretted that their erstwhile good neighbors should resort to a course of action which they, the Scots, regarded as open treason when judged by their own concepts of loyalty. They thought of Louis Riel as an opportunist, and when he sought to convert his dream of a French Canadian Republic [11] in the West into reality, it was easy for him to arouse his own people and to convince them that under a Canadian government they would lose their homes, lands, and hunting and fishing rights.

Many of the young men who were coming into the settlement at this time from Ontario were staunch Orangemen who were highly incensed at the shooting of their lodge brother, Thomas Scott, [12] by a metis firing party under orders of Louis Riel. The Kildonan folk always felt that if it had not been for the animosity stirred up by the agitators among the Ontario Orangemen no real trouble would have developed - if at the same time the Canadian government had shown a little tact in handling the Red River surveys. As it was, Riel's uprising came to an end when Colonel Garnet Wolseley arrived with his Red River Expeditionary Force [13] in August 1870 and found that the metis leader and his followers had fled.

When Manitoba entered the Confederation of Canada in 1870 the population was 11,963. [14] In this total were the descendants of the thirteen families who had remained loyal to Lord Selkirk in 1815 together with the other Scottish settlers who had come to the settlement between then and the early 1830s. A large part of the population was made up of Hudson's Bay Company men who had come to the settlement on retirement and settled along the Red River below the Scottish Settlement. There they received the same land grant from the Hudson's Bay Company as had the settlers from Lord Selkirk.

(1881) - This was the thirtieth year at Kildonan and the closing year of his ministry was marked by a religious awakening. A series of evangelistic services created an interest among young people and a revival of religion among the old. The prolonged strain of these told heavily on his weakening frame. He went to Toronto to regain his strength.

The General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church was prepared to honour him that year by appointing him Moderator. Ten Presbyteries had nominated him, but he declined the honour owing to the uncertain state of his health.

His death took place in the Manse of Kildonan on a Sabbath morning, February 12, 1882. So passed on an ardent social reformer, a friend of education, a public-spirited citizen, zealous for the advancement of all noble institutions in church and state. He left a name equally revered by the white settlers of all denominations and the Christian Red Men of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta.

They Went Forth, John McNab, 1933

In addition to these two groups there were the French speaking natives, and families of freemen from the fur trade, who had come to Red River from the west and north to settle in St. Boniface and along the Assiniboine River to as far west as Portage la Prairie. There were as well a few Canadians, as the old timers called them, who had come into the settlement from the east during the decade preceding Manitoba's admission to Confederation. From 1870 onward settlers poured into the country over the Dawson Trail from Fort William, from the south by sternwheel steamer from Fisher's Landing on the Red, and latterly, in the 1880s, by Canadian Pacific Railway from the Lakehead.

As the second generation of Selkirk Settlers required more land they crossed the river and cleared and cultivated the strips which had originally been granted to their families as wood lots. Thus Kildonan, West and East, became a closely knit community made up almost entirely of the descendants of the original settlers. It was not until after the First Great War (1914-1918) that Kildonan became, as it were, a part of Greater Winnipeg.

The Lord Selkirk folk are now scattered far and wide. Only a few families remain on the original grants. In the compass of 150 years or so great changes have taken place between the old order and the new, and because of this one is apt to forget, perchance has never known, that Kildonan was for many years not only the original agricultural settlement [15] west of the Great Lakes, it was the only one.

1. Hudson's Bay Flats - "Behold then Captain George Marcus Cary . and his experimental squad, some twenty in number, men and women commencing operations on that point of rich alluvial soil where the Assiniboine enters the Red River, adjoining the site of old (Upper) Fort Garry. Here a grand establishment was set up and a full supply of the most costly implements imported on a grand scale far beyond anything we had yet seen in the colony ... Nevertheless, though men and implements were set to work, two years had passed before twenty acres of mellow soil were under cultivation; nor at the end of ten years had this grand farming scheme extended another acre. The whole farm enclosed did not exceed eighty acres, and a fourth part of that was never under cultivation. On this contracted spot, Captain Cary and his operatives exercised their agricultural talents in raising wheat, barley, potatoes, and turnips - articles which everyone at Red River had for sale, and for which there was no market." - The Red River Settlement, Alexander Ross, pp. 212-213. "In 1837 he (Sir George Simpson) ordered more ewes and rams to cross with the Red River stock, and in the following year another Experimental Farm was set up. This time Captain George Marcus Cary came from England with a party of twenty men and women to set the experiment going ... Some butter, poultry, pork, and wool was produced, but in these things the experimental farm only took from the settlers the market with the Company which they had previously enjoyed. In the ordinary routine of farming, especially in grain, the settlers of 1840 were ahead of the model farmers." - Hudson's Bay Company 1670-1870, E. E. Rich, Vol. III, pp. 513-514.

2. Buffalo Hunt - "Not for some years (after 1818) was the colony to be independent of the buffalo hunts for its main supply of food. Even while the crops became more abundant, "plains provisions" remained a large part of the Red River diet." - Manitoba A History, W. L. Morton, p. 56.

3. Cruisies (Cruses) - The word is derived from Old English through the Middle English cruse - pitcher, a small vessel, jar or pot, for holding liquid (as water or oil). Icelandic-krus, a pot, tankard; Dutch-kroes, a cup or cruet. (Ed.)

4. Wild Berries - "We preserved our berries by drying. We used dry raspberries, saskatoons, and blueberries. They would dry in a cake and when we wanted some for the table we would break a piece off the cake and put sugar with it. The women used to pound choke cherries and put them in the pemmican ..." - Women of Red River, W. J. Healy, p. 101.

5. Lamps - "My father used to go to St. Cloud and St. Paul with the carts across the plain and I remember him bringing from St. Paul a glass lamp for which he had paid ten shillings. It was one of the first glass lamps in Red River. That was in the late 1860's. He brought a keg of oil with him and also a keg of molasses, and I remember that before we were through with that keg of molasses the taste of coal oil got into it some way." - Ibid, p. 102. "In the early years of settlement, a primitive form of lamp, which was merely a bowl of grease with a twisted strip of rag hanging over the edge and serving as a wick was used. Later the use of candles became general." - Ibid p. 81.

6. Carron Stoves - "The church (Kildonan Presbyterian) was heated by Carron stoves. My father used to import these from Scotland. At first there were two of these stoves in the church ... They stood near the door and the stovepipes from each went along, one over each aisle to the chimney in front. There were little kettles hung from each joint in the stovepipes to catch sooty drip. Although the stoves were started early on Sunday mornings and in the middle of Thursday afternoons for the meetings on Thursday evenings, it was sometimes hard to keep the church from being uncomfortably cold. A third Carron stove was put up in front of the church and before each service a pile of wood all ready for use was stacked near it, and one of the elders would step up from the elders' pew in front of the pulpit and put wood in the stove whenever it was necessary." - Ibid p. 75. The house she (Mrs. E. L. Barber) lives in is heated by one of the old Carron box stoves from Scotland, which were the first stoves brought to Red River. It has no pan in front of the door. On its smooth top bannocks were often baked. Some-times an oven was placed on top of the Carron stove." - Ibid p. 141. There were large foundries and iron works at Carron, Scotland, hence the name Carron stove. The name is also preserved in an obsolete snub-nosed cannon, the Carronade. Carron stoves are on display at Ross House and Seven Oaks House (Winnipeg), and in St. Andrew's-on-the-Red (Lockport). (Ed.)

7. Grasshoppers (Rocky Mountain Locust) - "When, therefore, the crop of 1818 began to head, it seemed that the colony might be past its early trials at last. But the colonists were attempting agriculture in the midst of a vast wilderness, unbroken, undrained, uncontrolled; their tiny plots on the banks of the Red were at the mercy of tempest, flood, or pest. On August 2, locusts descended in swarms on the crops. In places they were three inches deep on the ground. The wheat, fortunately, was so far advanced as largely to escape. The locusts deposited their eggs in the colony and the following spring the young were at work in May. This time they stripped the plots and even the prairie so that there was little grass for hay. Not only was no grain left for food, but little or none for seed ..." - Manitoba A History, W. L. Morton, p. 56. "As early as the latter end of June (1819), the fields were overrun by this sickening and destructive plague; nay, they were produced in masses, two, three, and in some places, near water, four inches deep. The water was poisoned with them. Along the river they were to be found in heaps, like sea-weed, and might be shovelled with a spade. It is impossible to describe, adequately, the desolation thus caused. Every green substance was either eaten up or stripped to the bare stalk; the leaves of the bushes, the bark of the trees, shared the same fate; and the grain vanished as fast as it appeared above the ground, leaving no hope of either "seed to the sower or bread to the eater." - The Red River Settlement, Alexander Ross, pp. 49-50.

Colonel Wolseley's tent at Thunder Bay (Port Arthur). Before striking camp at this place, Wolseley issued the proclamation to The Loyal Inhabitants of Manitoba. Public Records Office, London, W.C. 107/9, No. 2.

8. Flood(s) - "The destiny of the Selkirk Settlement was irretrievably linked to the two rivers, the Assiniboine and the Red. Both were normally placid streams that wound their way across the prairie lands to their meeting at the forks and then continued harmoniously to empty their combined waters into Lake Winnipeg ... The settlers felt an affinity for their rivers and they gave them an ungrudging respect but they did not trust them, and for good reason. When only one of them went on a rampage almost all activity ground to a stop. But when the flood water of both struck the settlement at the same time - there was utter chaos." - In The Beginning, Gwain Hamilton, p. 101. "... the country presented the appearance of a vast lake, and the people in the boats had no resource but to break through the roofs of their dwellings and thus save what they could. The ice now drifted in a straight course from point to point, carrying destruction before it; and the trees were bent like willows, by the force of the current. Hardly a house or building of any kind was left standing in the colony." - The Red River Settlement, Alexander Ross, (on the flood of 1826), p. 103. The breadth of the flooded area in our part of the settlement is eight or nine miles while the ordinary width of the river is not more than one hundred and fifty yards." - From a letter of the Reverend John Black (on the flood of 1852) dated May 27.

9. Reverend John Black - "... on the urging of John Ballenden, who was then Governor in Fort Garry, is conjunction with the reference in the matter by the Church of Scotland to the Reverend Dr. Burns, the pastor of Knox Church in Toronto, John Black, who late in 1840s was working as a missionary in Quebec, and who spoke French as well as English (though his lack of "the Gaelic" was at first a grievious disappointment to some of the older people in Kildonan) was sent to Red River." - Women of Red River, W. J. Healy, p. 65. "On his (Black's) arrival (in 1851) the Presbyterian people who numbered about three hundred ended their attendance at the Church of England services, and thekirk of Kildonan was organized. The manse and school house had been built on Land given by the Company (HBC), which gave also, in addition to the three hundred acres of glebe (church) land, £ 150 toward the building of the church." - Ibid., p. 68.

Volunteer detachments of the Red River Expeditionary Force, the 1st Ontario Rifles and the 2nd Quebec Rifles, drilling at the Crystal Palace, Toronto, 1870.

10. Treason - "The armed resistance was a very aggravated breach of the peace, but we were anxious to hold, and did hold, that under the circumstances of the case it did not amount to treason. We were informed that the insurgents did not desire to throw off allegiance to the Queen, or sever their country from the Empire, but that their action was in the nature of an armed resistance to the entry into the country of an officer, or officers, sent by the Dominion Government. We desired, therefore, that it should be considered in the light of an unlawful assembly, although it might technically be held to come under the statute of treason." - Report of the Select Committee of the House of Commons, 1874, p. 102, evidence of Sir John A. Macdonald.

11. French Canadian Republic - "What the metis and their clergy wanted to obtain from the new regime was not only the assurance of the grant of individual political freedom, but also safeguards for the perpetuation in the new era of their distinct position of a community within a community. In short, they wished to obtain for themselves a position in the North-West similar to that which the French of Quebec had won for themselves in Canada ... they were seeking to safeguard their survival as a people, to perpetuate the "new nation" within the framework of the new order in the North West." - Introduction to Begg's Red River Journal, W. L. Morton, p. 31.

12. Thomas Scott - "The shooting of Scott was a blunder, so much a blunder that it is difficult to believe a man of Riel's quality could have committed it except under the compulsion of the guards' exasperation and the threat of an Indian rising fomented by Schultz. It was, unhappily, worse than a blunder - it was unnecessary. - Manitoba A History, W. L. Morton, p. 139. "By one unfortunate error of judgement - this is what the execution of Scott amounted to, and by one unnecessary deed of bloodshed, (for the Provisional Government was an accomplished fact), Louis Riel set his foot upon the path which led not to glory but to the gibbet." - Louis Riel, George F. Stanley, p. 117.

13. Red River Expeditionary Force - "The strength of the expedition was fixed at 1,200 men. The imperial quota consisted of the 1st Battalion, 6th Rifles (373 officers and men), a battery of Royal Field Artillery (four 7-pounder mountain guns), a detachment of Royal Engineers, and a portion of the Army Service and Army Hospital Corps. The Canadian Militia contributed two battalions, the 1st Ontario Rifles and the 2nd Quebec Rifles, of twenty-six officers and 350 men each ... The battalions were organized under Lieutenant-Colonel Fielden in Toronto where each volunteer was first given a strict medical examination. Those who were regarded as less than robust for the strenuous under-taking ahead were rejected. Lieutenant-General James Lindsay, Commander in Chief in Canada, also insisted on a healthy attitude. No one was to be signed on who was seeking revenge for the death of Thomas Scott." - A Life of Field Marshal Lord Wolseley, Joseph Lehmann, pp. 137-138.

14. Population - According to the first census of Manitoba, the population in 1870 was as follows: Indians - 558; metis - 5,757; English half-breeds - 4,083; whites - 1,565. Total -11,963. - Sessional Papers of Canada, Volume V, No. 20, 1871. "... the English-speaking colonists - the Kildonan Scots, the Orcadian Scots, and Irish half-breeds of St. Andrews, Middlechurch, St. James, and other parishes of the Assiniboine as far west as St. Mary's at Portage la Prairie, the Irish and Scottish pensioners - were the most numerous element in the settlement. - Introduction to Begg's Red River Journal, W. L. Morton, p. 12.

The boundaries of Assiniboia (The Lord Selkirk Grant) are here imposed on a road map to show the political divisions and landmarks which are now situated therein.

15. Original Agricultural Settlement - The Selkirk Settlers came to Assiniboia to settle and to farm, and the purpose of their being at Red River was to gain their livelihood from the land. Traders of both the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company had done some part-time farming at several posts before the arrival of the Selkirk Settlers, but it was neither their primary objective nor their major activity in Rupert's Land. Thus the Scottish farm settlement in Kildonan was per se the original agricultural settlement at Red River. (Ed.) "On October 7, (1812) he (Macdonnel) himself planted some winter wheat, covering it with a hoe ... So inauspiciously did systematic* agriculture begin in the Red River Valley." - Manitoba A History, W. L. Morton, p. 88. (* The operative word is systematic (proceeding according to system or regular method). (Ed.) "Nobody, to be explicit, except the Kildonan settlers and a few enthusiasts in the Lower Settlement, was very much drawn to agriculture in Red River; the fur trade, the plains hunt, the long summer trips, were the attractive and profitable occupations ..." - Ibid, p. 88.

Lord Selkirk died on April 8, 1820 at Pau, Department of Basses, Pyrennes, South France, and was buried in the Protestant Cemetery of Orthez, twenty miles away. (Photo courtesy Anne Matheson Henderson)

Page revised: 19 July 2009