by James B. Hartman

Continuing Education Division, University of Manitoba

Number 43, Spring / Summer 2002

|

The anomalous fact is that the theater, so called, can flourish in barbarism, but that any drama worth speaking of can develop but in the air of civilization. (Henry James (1843-1916); Letter, 1916)

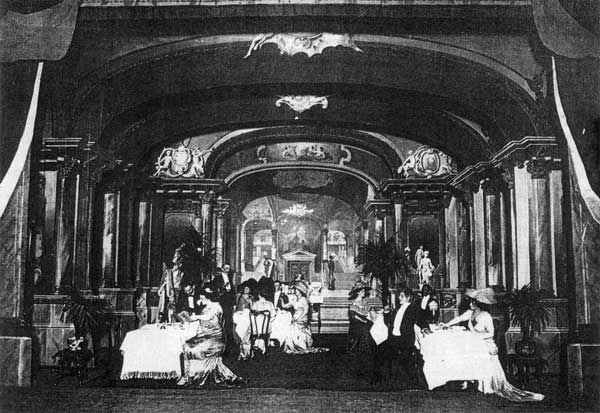

Theatrical presentation, Winnipeg, 1911.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

In 1870 there were only about one hundred residents of what three years later would become the City of Winnipeg, a tiny population living in a cluster of wooden structures stretched along the public highway. The following year, however, the population of the city more than doubled and over the next six decades it grew at a phenomenal rate, reaching approximately 213,000 inhabitants by 1930. This rapid population growth, and the accompanying economic development of the area that began in the 1880s and continued throughout the early years of the twentieth century, was reflected in the growth of theatrical entertainment in the young city. This article will chronicle the highlights of the theatre phenomenon—both buildings and events—from its beginnings to the late 1920s. [1]

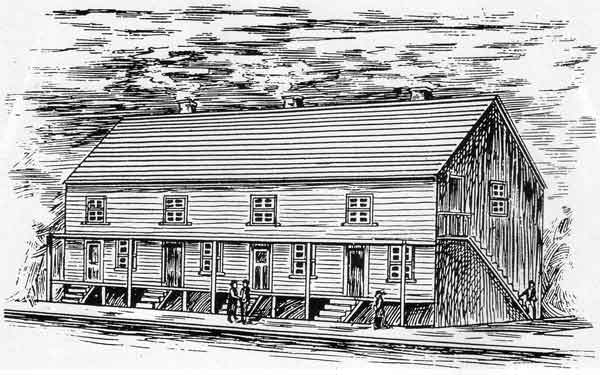

The early settlers soon tired of the simple delights of social intermingling and the anecdotes told by raconteurs at a hotel owned by “Dutch George” Emmerling; they craved more elaborate theatrical entertainment. The earliest record of such activity is when a group of enthusiastic young men of the Red River Settlement formed an amateur dramatic society in the fall of 1867. [2] They obtained the upper story of a building that contained several shops on the lower level, brought in benches for seats, set up a miniature stage with a curtain and oil lamps for footlights, and called their new space Red River Hall. This simple unadorned frame building had a precipitous outside staircase at one end of the building that served as the only entrance and exit to the theatre area. Winter heating was supplied by a couple of stoves, but the building, of course, was not fireproof. [3]

The opening performance began with a pantomime, followed by an original farce supposed to take place at Emmerling’s hotel. Since it was believed that the fragile theatre structure would not withstand foot stamping by the patrons, before each performance members of the audience were cautioned against this form of expression and applause was discouraged. The proprietors of the stores on the main floor used long poles to prop up the ceiling to prevent its potential collapse. A later store owner discontinued the theatrical performances on account of this risk. Red River Hall made a spectacular blaze when it was destroyed by fire in 1874.

Red River Hall, 1867. The building was destroyed by fire in 1874.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

Theatricals were a British army tradition for many years, and regiments at the outposts of the Empire in Canada relieved the tedium of garrison duty by presenting amateur productions that amused both the soldiers and the local populace. British soldiers who arrived in the 1840s and occupied both Upper and Lower Fort Garry performed farces imported from London for enthusiastic audiences inside the forts.

The officers and men of the First Ontario Rifles Musical and Dramatic Association, consisting of troops assigned to maintain order following the Riel Rebellion, decided to give a dramatic presentation. On 16 December 1870 they offered an opening performance in their new Theatre Royal, a renovated space at the rear of a store on McDermot Street owned by A. G. B. Bannatyne. They spent about $1,000—considered extravagant at the time—on elaborate decorations, staging, scenery, and accessories for a space that could accommodate over 200 people. The printed program described the event as “the first entertainment under the distinguished patronage of His Honour the Lieut.-Governor and Lady.” It began with comic songs and featured a dramatic presentation, The Child of Circumstances, or The Long-Lost Father, described as “A New Sensational Burlesque, in Three Acts, Never Before Played on Any Stage.” Various members of the dramatis personae were identified as “Monarch of all he surveys,” “a faithful follower,” “an interesting young man,” “a purser, and a villain,” “a child of circumstances,” “damsel,” “Tabby Feline, a real Cat, 20 years old,” “Soldiers, Sailors, Etc.” The program was repeated before crowded houses throughout the winter of 1870-71; patrons paid two shillings for box seats (armchairs) and one shilling for the pit (backless benches). There was general disappointment when the theatre closed following the last performance by the Ontario Rifles on 24 April 1871 as the regiment prepared to depart. Several private individuals who hoped to start a new theatre purchased the entire property, but their plans were not fulfilled, and the material was either sold or rented to visiting performers. [4]

The Quebec Rifles, who were stationed at the Lower Fort, also provided entertainments for residents of the area. On 18 February 1871 the Variety Club of the regiment offered a drama, The Gypsy Farmer, and a farce, Barney and the Baron, to an audience that had travelled from the Upper Fort and its vicinity. Performances took place in an old boathouse and these continued for a number of years. Two of the participants became professionals: one went to the United States, where he organized the Nathal Opera Company, which he brought to Winnipeg for a season in 1880 to present a widely performed work, The Chimes of Normandy; another joined the Babes in Toyland Opera Company. [5]

Another makeshift theatre was Manitoba Hall, a frame building on the north side of Bannatyne Street east of Main Street. Renamed the Opera House, [6] the ground floor space was used for dances and public entertainments, with dwelling apartments upstairs. When it opened on 3 January 1872 the Manitoba Variety Club performed Box and Cox and a melodrama, Robert Macair. In spite of stormy winter weather, people travelled considerable distances from Portage and Pembina, as well as from the Lower Fort and the Red River Settlements by dog train, to attend. The Albino Minstrels also appeared in the same month.

The Immigrant Building, located on a point of land at the junction of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, was fitted up for a minstrel performance toward the end of February 1873. In preparation for the event, building partitions were removed, planks on trestles were provided for seating, and a stage with movable scenery was erected. Six large stoves provided heating; it was a standing joke that the mud floor, at least, was fireproof! A newspaper critic praised the performance as a “tip-top affair” but complained about the lack of attention to the stove fires and the manner of reserving seats.

The Garrison Theatre at the Upper Fort, erected in connection with Fort Osborne Barracks in 1871-72 and operated by the soldiers, was the scene of many amateur performances during the winters of 1872-73 and 1873-74, sometimes as many as three a month. These consisted of light comedies and farces with such enticing titles as Cousin Pipes, The Limerick Boy, The Artful Dodger, The Double-Bedded Room, The Irish Tiger, Villikins and his Dinah, and Boots at the Swan. One member of the cast, Captain Thomas Scott, who had a role in Poor Pillicoddy in 1873, was described in a newspaper report as “one of the finest performers in the Nor’West.” Corporal C. N. Bell played leading lady roles many times. At the outset men played women’s parts, but this changed in the second and last season when women became the new favourites. [7]

The second Theater Royale opened in the winter of 187576, housed in a decrepit old shack with a false front on Main Street south. (It was originally built by William Hespeler as the Mennonite Hotel and later known as the Lorne House.) A section of the building stood on posts over a depression in the ground at the back of the theatre that was often used as a stable. It was not unusual for the animals being sheltered there to be heard during the quieter passages of theatrical performances taking place above, sometimes temporarily halting the proceedings to the amusement of the audience. (The artist’s drawing includes what appears to be a cow under the end of the building). In spite of the physical shortcomings of the facilities, the resident troupe of amateurs presented several ambitious plays, including Colleen Bawn and the perennially popular Ten Nights in a Bar Room.

The Second Theatre Royal opened in 1875 on Main Street. A stable occupied an area under the rear portion of the building—a cow can be seen under the structure in this artist’s sketch.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

In 1877 the recently formed Winnipeg Literary and Dramatic Association opened Dufferin Hall, which was a restoration of the remaining frame of Trinity Church that had been damaged by a cyclone in 1868 while still under construction and now was used as a warehouse. The Association’s first entertainment was a one-act comic drama, The New Footman. The cast of characters included Mr. Capsicum, Bobby Breakwindow, Miss Sourcrout, and Polly Picnic, and others with less quirky aliases. C. N. Bell, who had starred in female roles at the Garrison Theatre in the preceding year, now played one male part. The fevered anticipation of the eager crowd assembled for the oversold performance was so great that doorkeepers and ushers were pushed aside in the rush; many of the patrons who had paid for their tickets in advance were excluded, so considerable money had to be refunded.

The upper story of the City Hall, completed in 1876, provided seating accommodation for about 500 people. This pretentious building was ideal for public entertainments such as dances, concerts, and other amusements, although it was far from being a particularly elegant locale. The building had hot-air heating and was lighted by oil lamps but it lacked emergency exits and there were no ordinary safeguards against fire.

In March 1876 the City Hall Theatre opened with a charity concert in aid of the General Hospital. Cool Burgess, the first professional actor to appear in Winnipeg, and his troupe performed there on 24 July 1877 and on several following nights. It is probable that Lord and Lady Dufferin and their attendants were in the audience on the first night along with other “classes” of society. Other touring attractions included a magician-illusionist and a troupe of troubadours.

In the spring of 1878 the first theatrical advance agent to visit Winnipeg arrived from New York. The earliest theatrical production at the City Hall Theatre was on 17 May 1878 when a touring company led by Eugene McDowell from Montreal offered Lester Wallack’s Rosedale, followed by a series of farce comedies and musical extravaganzas. Some favourite offerings included East Lynne, The Shaughraun, Our Boys, Colleen Bawn, Mary Warner, The Two Orphans, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The McDowell Company was one of the most popular theatrical organizations to visit Winnipeg and they returned on several occasions; their Shakespearian productions always played to packed houses. The Marble Dramatic Troupe presented many old-time favourites during a week in March 1880. By 1883 the City Hall was deemed unsafe and in danger of collapse due to bulges in the walls, so the upstairs entertainments were discontinued, thus terminating another era in Winnipeg’s stage history.

In addition to “legitimate” (spoken drama) theatrical events there were a number of so-called “variety theatres” attached to bars or saloons patronized by men; they featured vaudeville shows and other entertainments. Variety theatres offered employment for women performers, many imported from the United States, but they were denounced in the press as “shops of harlotry” that should be suppressed on account of the women’s off-stage duties in enticing men to buy liquor in the attached bars or wine rooms. City clergymen and groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union were also united in their opposition to variety theatres on this account. A city bylaw prohibiting the sale of liquor in places of amusement diminished the profitability of variety theatres, causing them to close. [8]

Winnipeg was not deprived of a place of theatrical amusement for long because the erection of the Princess Opera House had been under way for some time. The brick veneered wooden structure was three stories in height with the main auditorium on the second floor; several stores occupied the ground floor. The impressive building and its furnishings cost about $75,000; it had a seating capacity of 1,378, including 278 plush chairs in the orchestra and eight private boxes with upholstered divans. A Winnipeg newspaper bragged that it was the finest and most commodious opera house west of Chicago, with the exception of a new structure in St. Paul. The visiting Hess Opera Company from Minneapolis inaugurated the hall on 14 May 1883 with a performance of Flotow’s Martha, followed by several other operettas on succeeding days.

Princess Opera House, Winnipeg, circa 1886. Opened in May of 1883, the Opera House could seat almost 1,400 patrons and cost approximately $75,000 to erect.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

Over a period of a few weeks after the theatre’s opening, several newspaper articles commented on the matter of appropriate behaviour by theatre patrons. Men were advised to observe such proprieties as not smoking, not wearing hats, not hanging their feet over balcony railings, and not returning tipsy after a few drinks between acts; women were asked to refrain from wearing large hats during performances. Theatre policy discouraged prostitutes from attending by withholding ticket sales for prominent and expensive seats; eventually they were segregated in a special curtained section of the theatre.

A dramatic entertainment later in the inaugural month was a six-day “Grand Shakespearian Event” consisting of Richard III, Othello, Hamlet, Macbeth, and The Merchant of Venice, featuring Thomas W. Keene, the popular tragedian, with a supporting company of actors. Many famous stage artists performed in succeeding months. A local stock company, [9] employing actors and actresses hired from New York, was connected with the Princess in 1887; it could not sustain its initial success beyond the first season and the manager left Winnipeg in 1890.

Although the main heating of the auditorium was from an inadequate hot-air furnace, in very cold weather several wood stoves were put into operation. It was the custom of patrons to huddle around these heaters to warm up between acts, and an employee was assigned to keep a careful watch on them whenever they were used, given the risk of fire. Even the lighting system was primitive; it involved pumping kerosene to the lamps by a special apparatus. In spite of various precautions the building was completely destroyed by fire on 1 May 1892 — headlined “Firey Finale” in next day’s Manitoba Free Press — following a performance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin by a visiting company. An editorial in the same newspaper two days later described the demolished hall as a “life-trap,” a “good-riddance,” and repeated earlier complaints about the unsafe design and construction of the building that had been ignored.

Victoria Hall was built in 1882; this brick veneered wooden building had several stores on the ground floor and an all-purpose concert and dance hall above. In 1890 it was renamed the Bijou Opera House — sometimes referred to as the Bijou Theatre in newspaper advertisements—when a local entrepreneur, Frank Campbell, renovated it to house a stock company that he had brought to Winnipeg. He built a new raised stage and added a narrow gallery to increase the seating capacity to about 800. The centre section of the main floor was raised but the side sections were left flat, thus effectively prohibiting good sight lines from the rear of the hall. Awkwardly placed pillars on each side of the stage supported an old-fashioned drop curtain that came down with a thump that shook the house at the conclusion of each act.

William Seach, the former manager of the destroyed Princess Opera House, took charge of the Bijou in 1892 and produced Romeo and Juliet, among other plays. Although students at St. Boniface College had presented a comedy by Moliere in 1891, interest in dramatics lagged, and entertainment turned more to music and professional offerings in larger theatres. The Bijou was home to the Winnipeg Operatic Society during the 1890s. Stanley Adams, who was active in the Society, wrote, acted, and staged plays; two of his popular comedies were Merciful Powers and Quits. When Adams and his wife left for England in 1901, many festivities took place in their honour.

William Seach operated the Bijou until 1896, when he and his former partner at the Princess, Charles Sharp, rebuilt Wesley Hall, an old church property, to provide a theatre space above several stores, and called it the Grand Theatre. It opened on 26 October 1896 when a local cast presented Verdi’s Il Trovatore. The flimsy structure burned down on 17 January 1897. Seach and Sharp then acquired an old brick veneered warehouse on McDermot Street and converted it into a hall seating 800 people, calling it the Grand Opera House. This building was unique at the time because it was the first theatre with its auditorium on the main floor and was lighted with electricity. Stage presentations included a repertory of standard plays from the Metropolitan Opera House New York. However, it was not a profitable venture because the managers were unable to obtain enough suitable attractions of good quality, and C. P. Walker (see below) was providing much competition by his bookings through New York, so the theatre closed in 1900.

In 1897 Corliss Powers Walker (1853-1942) and his wife, Harriet, a former musical comedy actress on the New York stage, moved to Winnipeg from Fargo, North Dakota, at the suggestion of the president of the Northern Pacific Railway who understood Walker’s business aspirations in the field of theatre. Winnipeg’s position as the northern terminus of the rail line made the city America’s gateway to the Northwest. This provided opportunities for extending Walker’s Red River Valley Theatre Circuit, associated with the Theatre Syndicate in New York, which included several theatres he owned in North Dakota (his “Breadbasket Circuit”). Now Winnipeg theatregoers could enjoy the latest Broadway shows soon after they opened in New York, as well as international celebrities in operas and concerts. Walker’s financial arrangements made it possible for him to bring attractions to Winnipeg that otherwise would never have gone beyond St. Paul. [10]

Walker promptly leased the old Bijou—then owned by Confederation Life—and opened the renamed Winnipeg Theatre on 6 September 1897. The inaugural performance featured the tragedian Louis James in Spartacus, the Gladiator, described as the “biggest production of a classic play in this country, and one of the largest of any kind.” Four other major plays, including several by Shakespeare, were presented in the following days. The inaugural program announcement boasted that in terms of its size, stage, scenic equipment, and lighting, the theatre was superior to anything west of Chicago. Balcony seats were 50¢; main floor, $1.50; and boxes seating five, $10.00.

The theatre auditorium, which could seat 1,000 persons, remained on the second floor, an arrangement that was strongly condemned by the local newspapers on the grounds of safety considerations in case of fire. This controversy extended even through the year 1904, when several reports on safe theatre accommodation resulted in both city and provincial enactments. However, due to a technicality these regulations could not be made retroactive in the case of the Winnipeg Theatre. Newspaper editorials debated the question of the suitability of the building, arguing that it should be closed or the law changed, for city aldermen might be liable to an indictment if a disastrous fire should occur. However, the fact that the second-floor theatre, located over stores, was admittedly not wholly fireproof did not prevent its active use. The theatre burned down on 23 December 1926, taking the lives of four firemen.

During its relatively short life, the Winnipeg Theatre sponsored presentations by various dramatic and operatic touring companies. The tragedian Thomas Keene performed again, and audiences welcomed such popular plays as The Gay Matinee Girl, The Widow Goldstein, and Tennessee’s Pardner with “new and magnificent scenic effects.” The Winnipeg Theatre Company, a dramatic stock company, also played there, along with the Permanent Players, another local stock company connected with the Dominion Theatre.

In 1901 Winston Churchill gave a public lecture on the Boer War.

The Dominion Theatre opened on 12 December 1904; it was intended for “high-class” vaudeville “such as ladies and children may properly patronize.” The solid brick building had a 1,100-seat auditorium on the main floor, and both its balcony and gallery were equipped with steel fire escapes. It had a self-contained electric lighting system and a steam heating apparatus, features that complied with new public safety regulations. The theatre was home to the Permanent Players, a stock company that was popular in the period 1910-1912. Soon after it opened the theatre joined an extensive circuit of vaudeville theatres in the United States. Over the years it also sponsored many amateur performances; it hosted a musical stock company and the John Holden Players. The Dominion also served as a movie theatre and eventually became the home of the Manitoba Theatre Centre. In 1968 it was demolished to make room for two major downtown buildings.

Another vaudeville playhouse in Winnipeg was a new theatre named the Bijou, which opened on 15 January 1906. Its owners had a large circuit of vaudeville houses in the United States. The initial performances — three shows daily — for the opening week of this “family theatre” for “refined vaudeville” consisted of comedy acrobats, a wire act, stunts, and a one-act comedy, The Silk Stockings, featuring the Four Ellsworths. For a popularly priced playhouse it was unusual for the interior to be decorated with plaster relief figures and trimmed with gold. The solid brick building had an interior fireproof wall and was heated by steam. The theatre was considered to be one of the best-conducted and most popular amusement places in the city. Later it became one of Winnipeg’s first movie theatres.

The cast of Robin Hood at the Bijou Theatre, February, 1895.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

While he was still manager of the Winnipeg Theatre, C. P. Walker decided to build a safer, more modern, and imposing playhouse that would comply with the very stringent requirements of the new Public Buildings Act. (Safeguards against fire had become an important consideration following a theatre holocaust in Chicago that killed 602 people on 30 December 1903, which some blamed on the greed of its syndicate.) Even before his lease for the Winnipeg Theatre expired he acquired the site for the building still known as the Walker Theatre. He visited other cities in the fall of 1905 to get ideas on contemporary theatre design. He also consulted with Howard C. Stone, a well-known Montreal architect, who also inspected the best theatres in the United States before beginning work on the plans. Construction began in March 1906 and was completed by the end of the year in spite of labour disruptions and delays in materials and fixtures. Walker had scheduled several bookings for late December that could not be cancelled without losses to him and the companies. Accordingly, several performances went ahead, including one by the Pollard Australian Lilliputian Opera Company on 17 December 1906, even though many things were incomplete at the time, making it the first performance in the new theatre.

Announced as the “Finest Play-house in the Dominion—Absolutely Fireproof,” the physically imposing building had a strikingly original interior. The ornate vaulted ceiling, sixty feet in maximum height, and the megaphone-shaped interior space contributed to excellent acoustics, well suited for the quality live entertainment for which the building was designed. There were no posts or pillars supporting the two balconies, so all upper-level seats had a clear view of the stage. Several rows of seats in the upper balcony, known as the “gods” and reached through a separate staircase, were priced at 250 for school children and patrons of modest means who could not afford the top-priced $2.50 seats for the carriage trade on the lower levels. The 1,798-seat auditorium, lobby, and lounges had a luxurious splendour that surpassed anything in the entire West: Italian marble, intricate plasterwork, gilt trim, velvet carpets, silk tapestries, murals, crystal chandeliers, and other amenities. When completed, the building alone cost over $250,000; about fifteen years later Walker estimated the total cost of his enterprise at $400,000.

Interior of the restored Walker Theatre, 1999.

Source: Parks Canada

The theatre’s official opening on 18 February 1907 was a gala social occasion; the Lieutenant Governor, the Provincial Premier, and the City Mayor gave dedicatory speeches. The audiences, many in full evening dress, enjoyed a triple production of Puccini’s Madame Butterfly in English, just three years after the opera had opened in La Scala, Italy. Walker brought to Winnipeg the finest old and new plays, musicals, operas, and symphony concerts from New York, Boston, Chicago, and London. Among the outstanding productions that played at the Walker in its early years were Sappho, Carmen, Chu Chin Chow, The Ginger-bread Man, Mrs. Warren’s Profession, Peer Gynt, The Blue Bird, Peter Pan, Pygmalion, Comin’ Through the Rye, Little Women, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Blossom Time, Maid of the Mountains, and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, along with The Dumbells and the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company. The Quinlan Grand Opera Company from London stayed at the theatre and presented fifteen large-scale operas by major composers in a two-week period. The Stratford-Upon-Avon Players paid frequent visits. Shakespearian actors such as Robert Martell, Sir Johnstone Forbes-Robertson, and the perennial favourite Sir John Martin-Harvey also appeared. Other theatre celebrities included Sir Harry Lauder, Wee Georgie Wood, Ed Wynn, May Robson, Grace George, William S. Hart, Victor Moore, Blanche Bates, singers Feodor Chaliapin, Nellie Melba, Madame Clara Butt, Madame Ernestine Schumann-Heink, and many more. Over the years the Walker Theatre sponsored the most famous artists of the English-speaking world in plays, grand and light operas, concerts, and pantomime.

The theatre’s spacious stage could handle large, spectacular productions, such as a thrilling performance of the epic Ben Hur that ran for six days beginning on 8 March 1909, announced as “a mighty play staged on a scale of unparalleled splendour.” The touring company carried a special orchestra and 200 people were involved in the production. The highlight was the re-creation of a chariot race involving twelve horses pulling three chariots on treadmills before an enormous moving background depicting spectators. An ecstatic review of the event in the Manitoba Free Press appeared on the following day:

Only the language of the superlative with frequent notes of exclamation can possibly describe all the glories of “Ben Hur” produced at the Walker Theatre last night. From a staging and scenic point of view it is easily the most elaborate presentation ever given in Winnipeg and it should be a matter of pride to every patriotic citizen that only in about four theatres in the States would it be possible to as adequately mount the play as was the case last night.

Other animal performers that appeared in Walker Theatre productions included horses in Old Kentucky and Mazeppa, a cat in Kindling, bloodhounds in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, spaniels in The Barretts of Wimpole Street, camels in Kismet, and both goats and camels in The Garden of Allah.

Theatre program from the Walker Theatre, March 1922.

Source: Parks Canada

Much of the credit for the fine entertainment was due to the efforts of Walker’s wife, Harriet, who encouraged amateur productions, notably university drama groups and the Winnipeg Kiddies, a popular children’s vaudeville show that toured North America for several years. She also aided her husband in booking music and drama productions for the Red River Valley Circuit. She wrote intelligent and well-informed press material on theatre topics for all Winnipeg newspapers; she was also a member of the Canadian Women’s Press Club. The Walkers’ daughter, Ruth Harvey, later published a detailed and entertaining collection of reminiscences about life with her parents (“papa” and “mamma”) at the Walker Theatre. [11]

The Walker Theatre was also used for important social and political events, such as the 1912 debate on women’s rights between Premier Rodmond Roblin and suffragist Nellie McClung, a personal friend of Harriet Walker. In 1914 McClung had the starring role in The Women’s Parliament, a parody on the Manitoba Legislature dealing with men’s right to vote, in which she played the premier. These events advanced women’s suffrage and helped defeat Roblin’s government in a later election.

The Walker Theatre flourished until the 1920s when the Theatre Syndicate’s touring system collapsed. Walker compensated by bringing in British and American companies and by sponsoring local amateur productions and miscellaneous touring shows. Now the movies were becoming a more popular form of public entertainment; early motion pictures at this playhouse included Birth of a Nation and Intolerance. Walker closed his theatre in 1933 and the City of Winnipeg acquired it in lieu of taxes in 1936; it was then sold to a family that converted it wholly to a movie theatre. After serving as a cinema for several decades, following renovations it opened again for live theatre on 1 March 1991. Later that year the Government of Canada designated the Walker Theatre a site of national historical and architectural significance.

The Orpheum Theatre, one of the chain of Orpheum theatres in the United States, opened on 13 March 1911 with the Lieutenant Governor and his party in the audience. The opulently decorated and furnished auditorium could seat 2,000 people. Audiences paid from 100 to 500 for afternoon shows and from 150 to 750 for evening performances and they enthusiastically welcomed the twice-daily shows. The Orpheum became one of the leading vaudeville stages in Winnipeg, along with the Dominion, the Walker, and the Pantages. Among the top American entertainers that performed there were Ed Wynn, W. C. Fields, the Marx Brothers, Fannie Brice, Harry Houdini, Jack Benny, and Eddie Cantor; foreign performers included actress Sarah Bernhardt and British music hall star Marie Lloyd. Performances continued for thirty-five years.

On 8 February 1914 Alexander Pantages, the wealthy American promoter from Los Angeles, opened the newest theatre of his continental chain of theatres, also devoted to vaudeville. He hoped that this would be one of several he planned to acquire through Western Canada to expand his circuit. Initially the Pantages Theatre presented three performances each day, trying to outdo the two-a-day schedule at the Orpheum Theatre, which turned out to be a profitable tactic. Actor Spencer Tracy and comedians Stan Laurel and Buster Keaton were among those that played there. The heavyweight fighter Jack Dempsey challenged members of the audience to go a few rounds with him on stage. The theatre survived for nine years before closing in June 1923, opening again in the fall as the Playhouse for stock performances.

A number of factors contributed to the demise of professional theatre: escalating travel and production costs, unions’ demands for increased compensation for actors and technicians, and radio information and entertainment. Also, as indicated above, during the early 1900s the movies increasingly became the preferred form of popular entertainment, supplanting vaudeville shows and legitimate theatre; the first sound-synchronized “talkies” were screened in Winnipeg’s Metropolitan Theatre on 26 October 1928. Going to movies was cheaper, less formal, and more convenient than the theatre. However, something has been lost, as Ruth Harvey, writing in the late 1940s, explains:

It is this social intercourse in the theatre that we miss today. Movies do not supply it. To begin with, the business of going to the movies is as humdrum as going to the subway. Like the subway trains, the reels have been running long before you get there; they will run on after you leave. There is no form, no beginning or no end, and so there is no sense of imminence or of expectation. Just motion.

But there is still one essential difference. A movie audience is passive. In the theatre an audience watching real people acting a play is active. The spectators have a sense of participation, as well as appreciation. Something is being made then and there before their very eyes, and they have a share in creating it. [12]

Moreover, during the late 1920s the cinema chain Famous Players Canada Limited purchased legitimate theatres and vaudeville houses as they came on the market. To protect its investments in talking pictures, Famous Players

banned live performances in all its outlets, a move that effectively terminated theatrical touring in Canada. It was not until the creation of the Manitoba Theatre Centre in 1963 that Winnipeggers once again could enjoy theatrical presentations of the same quality they had experienced during the first two decades of the twentieth century.

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players ...Shakespeare, As You Like It, II, vii

1. For an account of part of this period see Carol Rose Budnick, “For Pleasure and Profit: Amusement and Culture on the Frontier, Winnipeg 1880-1914” (MA thesis, University of Manitoba, 1983).

2. Joseph James Hargrave, Red River (Montreal: Printed for the Author by John Lovell, 1871), 419. Hargrave’s account is embellished by Irene Craig, “Grease Paint on the Prairies,” in Papers Read Before the Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba, Series III, Number 3, ed. Clifford Wilson (Winnipeg: Advocate Printers, 1947), 38. This paper is not documented, but one of its sources probably is: An Old Timer, “The Early Playhouses of Winnipeg,” a booklet provided for the formal opening of the Walker Theatre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, 18-19 February 1907. (It is believed that “Old Timer” was C. P. Walker, who often used this nom de plume.) This latter publication is the primary source of information for much of this article. The booklet is in the Archives of Manitoba, file P2184-A f2. A supplementary source of information is E. Ross Stuart, The History of Prairie Theatre: The Development of Theatre in Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan 1833-1982 (Toronto: Simon & Pierre, 1984), 17-78.

3. Red River Hall was situated on the east side of Main Street on the site of the Lombard Building.

4. Stuart, The History of Prairie Theatre, 21.

5. Craig, “Grease Paint on the Prairies,” 41.

6. Although the name of this building, like others similarly labelled “opera house,” suggested that it was intended chiefly for operatic performances, this did not exclude other forms of entertainment. In fact, the custom was to use the term “opera house” to designate any theatre.

7. Stuart, The History of Prairie Theatre, 23.

8. For a detailed account of variety theatres see Carol Budnick, “The Performing Arts as a Field of Endeavour for Winnipeg Women, 1870- 1930.” Manitoba History (Spring 1986): 16-17; and “Theatre on the Frontier: Winnipeg in the 1880’s,” in Theatre History in Canada 4(1) (Spring 1983): 28-31.

9. A stock company can be defined as a group of actors with several different plays in its repertory, established in one theatre on a fairly permanent basis. This can be distinguished from a touring company, which travels from place to place performing its repertory of plays.

10. For a comprehensive account of Walker’s theatrical enterprises see Reg Skene, “C. P. Walker and the Business of Theatre: Merchandizing Entertainment in a Continental Context,” in The Political Economy of Manitoba, ed. James Silver and Jeremy Hall (Canadian Plains Research Centre, University of Regina, 1990), chap. 6.

11. Ruth Harvey, Curtain Time (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1949).

Page revised: 24 April 2016