by James M. Skinner

Department of History, Brandon University

|

The proliferation of film censor boards in Canada in the quarter century following the birth of the cinema mirrored, to a degree, the situation in the United States where, from 1907 onwards, state and city bodies sought to control the content of motion pictures. Each Canadian province had its own jurisdiction by the 1930s. [1] In 1972, Manitoba’s became—and remains—unique as the one where cutting and outright banning of specific titles was proscribed and only classification into categories permitted. This study examines the rationale for that decision, the legislation which brought it about, and the short and long-term consequences.

The Manitoba Film Censor Board was established in 1923 under legislation known as the Amusements Act. Staffing and modus operandi remained unchanged in their essentials from 1930 until 1972. All 16 mm and 35 mm prints for public exhibition, together with accompanying advertising, were examined by a chairman and two assistants. The parameters under which it operated were not dissimilar from those governing the so-called Hays Code, an industry document which enunciated specific guidelines and forbade certain themes. These latter included nudity, premarital sex, adultery as a permissible solution to an unhappy marriage, robbery when presented in detail and the depiction of criminals as sympathetic characters. In time of national emergency, the Manitoba board might also take cognizance of political considerations. Thus, at the outbreak of the Second World War, pictures with ostentatiously pacifist themes such as All Quiet on the Western Front and Journey’s End were kept off provincial screens for the duration of the conflict while Beau Geste was temporarily banned in 1939-40 at the request of the French government for its negative portrayal of the Foreign Legion. [2] In the immediate post-war period, horror movies were subjected to close scrutiny. It was asserted that the presence of mad doctors and psychiatrists in so many of them might have a deleterious effect on a specific segment of the population. Somewhat convoluted reasoning held that war veterans in need of mental care might have their faith in the medical profession undermined by regular theatrical exposure to Dr. Frankenstein and his ilk, or make them reluctant to enter an asylum if the frequent characterization of custodians of these institutions as themselves slightly deranged was allowed full rein. In short, it was unusual for a year to pass without some film being refused a certificate because it overstepped delineated bounds. [3]

A profound change overtook the North American film industry in the late ‘fifties and early ‘sixties. From an all-time high in 1946, admissions began an alarming and inexorable decline thereafter. Increased leisure time and wider variety of recreational and cultural opportunities than had been available to the general public before and during World War Two were important factors. But the most significant was almost certainly the challenge of television which went from being a temperamental, expensive toy at war’s end to a fixture in most living rooms a decade later. If Hollywood could not match black-and-white television’s immediacy in news and sport or its free programming, it had to find other means to lure the missing millions back to their seats. Colour, new formats—such as wide-screens and three-dimensions—or historical-cum-biblical extravaganzas, were seized upon as potential solutions. Another was daring. Television was continually being ridiculed as the bland leading the bland. The movie industry therefore determined to venture into hitherto forbidden pastures. Homosexuality, drug-taking, nudity, all practices which had been banished since the appearance of the Hays Code and the Catholic National Legion of Decency in 1930s, began to reappear. Too, a shortage of the Hollywood product led exhibitors to fill the gap with foreign pictures which were often considerably more outspoken than the domestic equivalent, boasting voluptuous, earthy heroines. Sophia Loren, Brigitte Bardot and Gina Lollabrigida, among others, became familiar faces to North America audiences in this era. It was evident that the family movie which had dominated screen entertainment from the inception of the cinema was a thing of the past. It was equally clear that exclusion of minors from adult entertainment was becoming a necessity. Faced with the possibility that either federal or state government intervention would result from public clamour, Hollywood decided to forestall such action by instituting its own form of regulation. For the first time, industry classification would apply, and on the basis of age. In 1968 the American Production Code Administration which had carried out Hays Office edicts was replaced with a Ratings Administration. An “alphabet soup” of letters—G, M, PG, PA, R and X—designating the new categories and conditions of admission made its appearance.

These were generally more permissive times. Attitudes towards premarital sex, abortion and drugs (at least the ‘soft’ variety) were undergoing a profound change. The see-through blouse and the topless waitress no longer caused the consternation of yore. Simulated sex on the Broadway stage in O Calcutta was being mirrored in the cinema which would soon go one better when Linda Lovelace came to display her remarkable thoracic talents in Deep Throat (1972). It became almost de rigeur for well-known actors and actresses to appear naked, albeit momentarily, even though only a decade before North American Censors had expected female navels to be covered at all times.

In Manitoba, the question of replacing censorship with a film classification system, based on the Hollywood model but administered by the provincial government’s Cultural Affairs department, had scarcely figured in the New Democratic Party’s platform on the eve of the 1969 provincial election. [4] Taking office for the first time, it soon became embroiled in what was to prove by far the most contentious issue of the Schreyer administration, Autopac, a government-run automobile insurance scheme. Thoughts of amending the Amusements Act were given low priority. Nevertheless, there were individuals in the party, notably Cy Gonick, an ostentatiously left-wing professor of economics at the University of Manitoba and editor of Canadian Dimension, who felt that censorship of the media by a non-elected body was repugnant to the ideals of social democracy. The first step in rectifying the situation was the creation of a commission in June 1970. A Review Board of seven citizens was charged with studying the existing legislation and canvassing public opinion. Both Una Decter and Wendy James declined to attend any of the hearings and did not participate in subsequent deliberations. The remaining five comprised C. M. Bowman, as chair, Paul Morton, Drs. Robert Brockway and Gordon Stephens, and Anne DuMoulin. Hearings were held in Winnipeg on 3 and 4 November, and in Brandon on 10 November, at which time fifty-three written briefs and oral presentations were submitted. Predictably, these ranged from demands for more rigorous film censorship to total abolition.

In its Report, the Commissioners opined that the Censor Board had become largely a classification body since it now did very little banning of its own volition. Statistics for the period 5 December 1968 to 9 September 1970 showed that of eleven features originally rejected, ten had subsequently been accepted after trimming by the companies or distributors concerned. Of 596 titles screened in that twenty-one month period, only seventeen had been subject to Board cuts, one for violence, three for obscene language and thirteen for sexual content. Furthermore, as the Report emphasized, the criteria for censorship in the 1930 Amusements Act were being largely ignored. Had they been stringently applied, with due cognizance taken of strictures against extra-marital affairs, attractive villains and the like, few pictures would have been shown in Manitoba in the ‘sixties. [5]

Twenty-six recommendations were made. The most important dealt with the abolition of the Censor Board and its replacement by a classification authority. It would comprise fifteen members of the public including a chairman, to be remunerated on a fee-for-service basis. The new board should have the right to veto and, if necessary, prohibit offensive advertising inside the theatre or elsewhere. With an eye to the American classification system, it was suggested that movies be divided into three categories—’General’ with admission to all without restriction, ‘General P’ where parental guidance should be a factor, and ‘Restricted’ with attendance limited to those over sixteen. Films rated ‘R’ could be further classified according to content under, for example, ‘L’ for language, ‘V’ for violence or ‘S’ for sexual content. The board would also reserve the right not to classify a film deemed to be in violation of the Criminal Code of Canada. [6]

Next to the suggested abolition of censorship per se, the most controversial recommendation was the institution of the Restricted label (the equivalent of the American ‘X’) which would supersede parental decision-making. A picture thus categorized would be off-limits to under-sixteens even if their parents or guardians were amenable to their viewing it. Nevertheless, it was made with the rapidly-changing scene in mind. In the United States the introduction of the ‘X’ had become a green light for pornographers. There was an explosive growth in the number of hard-core titles and of adult theatres screening them to the exclusion of all else. Behind the Green Door and Devil in Miss Jones had broken through a time-honoured, morality barrier which had limited exhibition of their kind of surreptitious, midnight shows in sleazy, back-street cinemas or service club stag nights when otherwise sober business and professional men momentarily shed respectability and inhibitions to sample guilty pleasures. Now they were on display in plush, first-run theatres from New York to Los Angeles. Deep Throat was one of the top forty moneymakers of 1972-73. Eager to profit from the new trend, Hollywood threw caution to the winds. Paramount released a version of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer while MGM’s Best House in London dealt with attempts to organize a government-sponsored brothel. Twentieth Century Fox hired director Russ Meyer, acknowledged “king of soft-core porn,” to make Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, a potpourri of lesbianism, homosexuality, transvestism, nudity and graphic violence while, as a condition of their contracts, reputable actors and actresses were being asked to appear totally naked. Scenes of simulated intercourse and dialogue laced with four-letter expletives became commonplace. In its final year of operation, the Manitoba Censor Board placed more films in its own restricted category than in any other, while the number of G-rated pictures fell to an all-time low. [7]

The government bill was introduced in the Legislature on 12 June 1972. It accepted many of the task force’s recommendations but erred on the side of liberality with respect to the age requirement. The Restricted label was to apply to those under eighteen, not sixteen. For the category “Parental Accompaniment” (PA), the juvenile would be required to have a parent or guardian in tow. The board was to have a part-time chairperson, a membership of fifteen and a full-time executive secretary whose duties would include inspection of theatres for age infractions. All films and trailers (coming attractions) would be seen by a minimum of three who would have to indicate the rationale for their verdict in writing. An appeals process would continue in existence for complainants, usually distributors, demanding a second verdict. The board would also exercise its predecessor’s powers by regulating advertising in the press and outside cinemas. Theatre managements and staff had the onus of checking on the ages of those seeking entry to R and PA rated films. Infractions of the law could result in the imposition of fines ranging from two hundred to two thousand dollars per offence. [8]

Sam Uskiw spoke in support of the measure on behalf of the absent Larry Desjardins, Minister of Tourism, Recreation and Cultural Affairs. Somewhat cautiously, if not altogether apologetically, he presented it as a compromise measure between conflicting ideological demands for total freedom and increased vigilance by maintaining the status quo:

I must say, from the outset, that I do believe in censorship although this bill is abolishing the Censor Board. I believe in censorship only on one condition—if I could do the censorship myself, and I’m sure that there’s (sic) 57 members in the House that feel exactly the way as I do, and I’m sure all the members of the press and the radio and so on, feel the way I do. It is virtually impossible to do any censoring. Therefore, I think the next best thing would be to assist the public. We can assist them by evaluation or ... in changing this board to a classification board. [9]

Sam Uskiw, member of the NDP provincial cabinet, 1969-1975.

Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index

The opposition was led off by Gordon Beard, Independent-Conservative MLA for Churchill. He charged the government with abdicating its responsibility by abolishing the old board. Moral principles were involved and the party in power was duty-bound to take a lead where those were concerned. Members opposite should expect negative responses if they forced the measure on the House thereby allowing

... the smut manufacturers of the movie industry to come in, not only bringing stag movies in to the movie houses ... but bringing in movies that would make the stag movies of olden days look pretty presentable today. So I say you’d better take another look at it ... [10]

When debate was resumed on June 20, the argument became more heated. Conservative J. Wally McKenzie wondered what kind of showman would turn away customers because of their age, and what kind of government in a democracy would charge a youngster under the Juvenile Delinquency Act for the sin of lying about his date of birth. There would be a need for individuals to carry identification at all times; but he questioned whether the province had the moral right to indulge in this sort of quasi-totalitarian behaviour. The strongest criticism of the measure came from Joseph Borowski who had recently quit his ministerial post as Highways Minister. His disillusionment with the party over its moral stance on this and, subsequently, the abortion issue which would cause him to sever all ties with the NDP and become one of its bitterest opponents, was vented:

I simply cannot accept the government’s casual stand on character-destroying, dirty and degrading pornography that is sold on our newsstands and shown in our theatres ... Looking back ... things haven’t changed a lot since I resigned from cabinet. The government, rather than retrenching and rethinking their position on some of the social and moral issues facing society, seem to be going forward and trying to make Manitoba the Sodom and Gomorrah of North America ... Perhaps we should have a new sticker, ‘Will the last moral person leaving Manitoba please turn out the lights?’ [11]

Joe Borowski, NDP member of cabinet, 1969-1973.

Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index

In coming to the government’s defence, Attorney-General Al Mackling was at pains to emphasize that passage of the bill would not be an open sesame for pornographers. His office had already prosecuted some of those, and would continue to do so. But he doubted whether the majority of people in the province really wanted his office to “prowl and snoop.” He would continue to act on the basis of individual complaints. These would be investigated and dealt with as the situation merited. [12] Donald Malinkowski, a priest and N.D.P. backbencher, was not reassured by those on the front bench. Was it not true, he asked rhetorically, that we are all limited by what society deems permissible? Why give the film industry the kind of unfettered moral licence denied the individual? The sex act is a private affair. A third party observing it is rightly referred to as a Peeping Tom and regarded as morally depraved:

To me there is something sick in our society to see hundreds of seemingly normal adults sitting in a theatre like so many Peeping Toms, watching nude, simulated sex acts on screen ... Complete abolition of censorship over films would put this province in line with Denmark. Denmark had achieved a great, popular reputation for its export of excellent bacon. It is becoming better known now for its export of smut, and many Danish people are not happy about this development. And I am convinced ... that the majority of Manitobans do not want to follow the Danish example. [13]

Attorney-General Al Mackling, 1973.

Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index

Resistance to this line of argument, bacon on the contrary, came from two of the more vocal members of the government. Theirs was an amalgam of libertarianism and scepticism over the conceit that morality could be legislated, that people could somehow be made ‘good’ despite themselves. Russell Doern sought to distinguish between the erotic and the smutty. The former was an integral part of much of art and should not be condemned. He pleaded for acceptance of a film that might have distasteful elements but was, nevertheless, a work with redeeming social value. Such was Joe, the story of a redneck bigot. It contained nudity, bad language and that Aunt Sally of the censors, ‘controversial lifestyles’ but was praiseworthy, in his view, because it graphically illustrated the dangers of the drug culture and the intolerance of the so-called silent majority of Americans towards rebellious youth. In passing, Doern noted that it had been subject to criticism in other jurisdictions before arriving in Manitoba. Nor was the existing system operating as smoothly as some of its defenders implied. He quoted the case of The Stewardesses (1971) whose amoral protagonists had their pneumatic charms further enhanced by three-dimensional presentation. After cuts had been made as demanded by the provincial board, it had been certified “R” thus permitting exhibition in the province. However, within days of its opening in Winnipeg, it was seized for obscenity by the morality squad. The ensuing court case had been resolved in favour of the defendants on the grounds that they had reason to believe a Censor Board certificate was an imprimatur to exhibit the film freely. [14] Sidney Green, who would also part company with the NDP and form his own (Progressive) party, denied the efficacy of government control over social behaviour. The sale and consumption of alcohol and movies were regulated, and yet there were constant problems with both. The bill was an improvement, to some degree, because it dismissed the notion that there existed a group of Manitobans possessed of superior wisdom with the right to deny the rest of us that which they deemed unfit to see. Censorship tended to promote rather than stifle pornography. Free citizens in a free society with outmoded constraints thrown to the wind would rob the pornographer of the ability to ply his trade profitably. As the old saw had it, ‘To be virtuous is easy when sin ceases to be a pleasure.’ [15]

The opposition had some fun at the government’s expense by contrasting the philosophy motivating the bill with recent Autopac legislation. L. R. (Bud) Sherman expressed gratification that honourable members across the House were now supporting freedom of choice and a concomitant curb on government interference. Would they had shown the same solicitude when the future of private motor-vehicle insurance was being sacrificed on the altar of socialist dogma. His main concern was with the film that received an ‘R’ label under the new system but could still be defined as pornographic under terms of the Criminal Code. Would the theatre-owner be liable for prosecution even though the Board had not deemed it so? [16] Harry Graham questioned that part of the bill preventing parents from taking their children to Restricted pictures under any circumstance. He could only hope that there was no intention on the Attorney-General’s part to prosecute those who did. [17]

This last concern was taken up at some length by Israel (Izzy) Asper, the newly-elected Liberal MLA for Wolsley, and soon to become a formidable force in the entertainment industry through his commercial television interests. He sought, in vain, to have the exclusionary clause for Restricted pictures modified. Absurd situations would arise where a husband was prohibited from taking his seventeen-year-old wife to a show, or a couple denied entry to a drive-in because their infant child, asleep in the back seat, was accompanying them of necessity. He also deplored the government’s refusal to give theatres advance rulings on the possible dangers they ran in screening contentious titles.

The result, he predicted, would be self-censorship through fear of criminal prosecution. That would be a regressive but necessarily defensive move by management. [18] Debate in the committee stage did result in a slight modification of Bill 70. Section 28.1 gave the theatre owner some protection if it could be shown that the individual admitted to a Restricted performance appeared to be of statutory age, that the staff had no reason to suspect otherwise, and that the minor had supplied bogus or faked evidence that would normally be accepted.

Nevertheless, when the measure came to a vote, members split very much along party lines. Two, Borowski and Jean Allard, another defector from New Democratic Party ranks, joined the ‘nays’; and the remainder of negative votes came from the opposition Conservatives, four Liberals and Jake Froese, the lone Social Credit member. Like the Battle of Waterloo, it was a damned close-run thing with the government’s victory margin twenty-seven to twenty-six. The legislation came into effect on 20 July 1972. [19]

Its passage occurred at a particularly critical time for the Board. For much of the previous year it had been a one-man operation since its executive director, Charles Bieseck, had lost two colleagues through resignation. He was left with the onerous task of cutting and/or rating each movie entering the province which left him insufficient time for carrying out his other mandate, that of vetting advertising outside theatres and in the media. Increasingly, film companies were using T.V. ‘spots’ to publicize coming attractions by showing scenes from products that might not have been submitted for examination. His cri de coeur to the Attorney-General not only expressed opposition to the forthcoming legislation but also wistful nostalgia for a bygone age:

It is the most demeaning job to watch this garbage day after day as if it rated to be considered serious art. We are faced with the fact that hard-core pornography is being purveyed by smut-peddlars with hard-sell techniques ... The movie makers are determined to go to the very limit in obscene and pornographic content they cram into their films. The same is true in the advertising of these films. The press quoted you as saying you are not in favour of censorship. This used to be my view before I started viewing films for the Censor Board ... At one time not so long ago we also had laws which restrained moviemakers from showing pornographic films. At one time the film industry itself had a moral code to guide filmmakers in the production of movies. This has now been completely abandoned. Now everything goes and film producers vie with one another as to who can put the most smut in films. Until all filmmakers are made to con-form to certain standards of morality and decency, there is not much censor boards can do to improve the standards of films shown. [20]

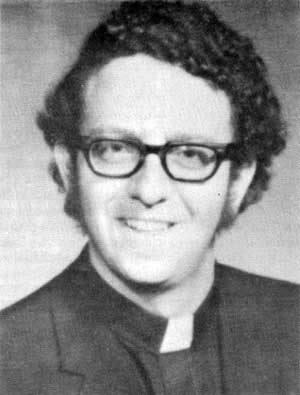

Members for the new Board, in common with those of other commissions in the province, would be selected from among rank-and-file supporters of the governing party. Of necessity they had to have both the time and the inclination to devote four or five days a week every month or so to the task. Bieseck was retained, despite his misgivings, but the chairmanship went to Father John J. Pungente, a young, well-known Jesuit school principal with a Master’s degree in film studies from San Francisco State University who also ran classes in film appreciation at St. Paul’s High School. [21] There was, nevertheless, an element of being thrown in at the deep end for many of the other classifiers who were not necessarily inveterate moviegoers. Some who had seen little or nothing since the bland, halcyon era of Hollywood never recovered from the shock of their first glimpse of full-frontal nudity or simulated intercourse. Others were either more battle-hardened or became cynical through regular exposure to indecent antics on-screen.

Rev. John Pungente, Chair of the Manitoba Film Classification Board, 1972.

Source: St. Paul’s High School

The early seventies marked the zenith (or nadir) of the sex exploitation picture for North American audiences. Manitoba fared no differently from other provinces in the number of such titles submitted. The difference lay, rather, in the degree of protection offered the distributors in other jurisdictions as a consequence of excisions of questionable visuals and dialogue which might otherwise be used as evidence in a legal action. Since the same film could, in theory, run uncut in Manitoba, its vulnerability to criminal prosecution was commensurately greater. Conversely, it might be submitted in its original form if the calculation was it would run a better chance of being screened there than elsewhere in Canada.

In those early years of its existence, three tendencies were evident in the Classification Board’s dealings with the industry. First, there was often lively, internal debate over the merits of specific pictures which had achieved critical acclaim or notoriety. Such was the case with Last Tango in Paris (1972) directed by the respected Bernard Bertolucci. This allegory of love, rejection and despair included nudity and a scene of simulated anal intercourse. On this occasion, most Board members, rather than the statutory three, were present at the screening. Opinion was sharply divided between the majority (which included Father Pungente) who considered it a worthy piece of cinematic art, and the remainder, led by Bieseck, who condemned it as utterly disgusting with few, in any, redeeming features. Having been granted a Restricted rating, it was seized by the Winnipeg police within days of its opening and landed the distributor, United Artists, in court where a successful defence was conducted. [22] Second, the Board was not always guiltless in applying a double standard. Statistics show that titles emanating from prestigious Hollywood studios, with big budgets and recognizable stars, appear to have been treated more leniently than cheaply-made equivalents from studios that turned out a steady diet of ‘skin-flicks: In this regard, the fate of The Exorcist (1974) is illuminating. Warner Brothers were the producers of this multi-million dollar drama of devil possession. It features Linda Blair as a twelve-year-old whose mind and body are taken over by a demon. The child utters a string of obscenities, many of which are aimed at a Catholic priest asked to perform the exorcism. In one sequence, she urinates on the living-room carpet before a roomful of horrified onlookers. Bieseck’s rationale for the Board’s acceptance of The Exorcist makes interesting reading:

There was ... unanimous agreement that this film was in part obscene and, in general, a most disgusting film. However, it would have been futile and caused lots of embarrassment all round had our Board tried to stop the showing of a film in this category. This was a costly film. It was a major production (author’s italics) which had already aroused much controversy. In this instance only the Attorney-General’s department could have stopped the action—an action which would have been inadvisable in view of the prevailing obsession with the occult, demonology, etc. [23]

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that, fortuitously or otherwise, there was one law for the rich and another for the poor relations of filmdom. One should, perhaps, bear in mind that, since distributors and exhibitors have to pay a fee for classification of their product, the larger studios and theatre chains are more able to absorb these costs than independents or ‘mom or pop’ cinemas.

Third, the Board did exercise a form of pre-classification censorship when there was a consensus that a film was utterly objectionable and probably in contravention of the Criminal Code. In those few instances, a form letter was sent to the distributor with copies to the Minister of Cultural Affairs under whose aegis the Board now operated, as well as to the Attorney-General’s office, the chief superintendent of the RCMP and the Winnipeg City Police chief. This advised the parties concerned that, in its existing form, the movie was liable to prosecution under the Criminal Code. [24] The number of instances when this was carried out rose from four in 1972 to eight in 1973 and twelve in 1974. In every case, no major company was involved, giving further credence to the theory that the prestigious were treated with more deference, although, in fairness, it must be admitted that the majors had proportionally less sex in their product. Occasionally, projectionists took it upon themselves to remove footage which they suspected failed to meet prevailing standards, and one was driven to write the minister concerned justifying his action. These excisions occurred exclusively in those Winnipeg independent theatres specializing in ‘adult’ pictures, and not at all with the national chains. [25]

In the final analysis, it would seem that neither the doleful prophecies of the traditionalists nor the hopes of the permissives were realized: The abolition of movie censorship in Manitoba did not lead to a greater inundation of pornography there than in any other jurisdiction in Canada. Nor was concerted pressure applied by companies to foist hard-core material on it. If the number of titles deemed unsuitable for public exhibition soared in the 1970s, there was a commensurate increase in every other province. Indeed, the lack of stringent guidelines may well have had the opposite effect and caused distributors to be doubly cautious. The long-standing custom of shipping prints from Ontario, where they were subject to the most rigorous standards in the nation—as imposed by its Censor Board’s chairwoman, the formidable Mary Brown—continued, though a perusal of the debates in the legislature fails to find any awareness of this procedure among MLAs who, understandably, were not conversant with distribution practices. There was a ‘play safe’ tendency not to restore footage which had been removed by the Toronto guardians of morality. Thus, Manitoba patrons of even soft-core pictures might well view prints where half the running time or more had disappeared as a result of action by a sister province. [26] As with much else in the entertainment industry, Toronto ordained and the rest of the country followed suit. [27]

The appearance of the video cassette in the early ‘eighties signalled the beginning of the end for public screenings of ‘skin flicks’ which had consumed much of censors’ energies for decades. It also hastened the demise of cinemas and drive-ins largely devoted to their exposure. [28] Though legally unobtainable from outlets in Manitoba, hard-core pornographic tapes were freely advertised in the press by firms in British Columbia, Quebec and, more recently, Ontario. The size and relative unobtrusiveness of a cassette (as distinct from a 16 mm print) also made it easy for vacationing Manitobans to ‘import’ them from the United States. The failure of three provincial jurisdictions, Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, to devise a common ratings system for videos in the mid ‘eighties delayed introduction of the process in Manitoba until 1991. Even now, the Herculean task of attaching ratings labels to thousands of non-current and non-theatrical titles is far from completion. Tapes for outright sale seem to be exempt altogether.

It may be said, without fear of contradiction, that far more Manitobans view feature films in their homes than they do in theatres. Access to adult-rated material presents little difficulty for enterprising juveniles. The irony of the situation has not been lost on exhibitors who ask, with some justification, why they are liable to prosecution for allowing an unaccompanied sixteen-year-old entry to a Parental-Accompaniment or Restricted film when he or she is able to rent or purchase it from a retail outlet. Pay-television, with its boast of showing original, uncut versions to those willing to pay the monthly fee, compounds the inequity. Here is a censorship problem requiring the judgement of a Solomon that may never be resolved.

1. During the Great Depression, and as a cost-saving measure, the Saskatchewan censor was domiciled in Winnipeg and sat in on viewings with his Manitoba counterparts, a situation which remained in effect until the end of the Second World War. Newfoundland, since its entry into Confederation, has used the services of the New Brunswick censor.

2. See the author’s “Clean and Decent Movies” in Manitoba History, Number 14, Autumn/87, pp. 2-9. There was some furor over the 1939 version because, in the opinion of the French government, its negative image of the Legion might be detrimental to recruitment. Objections were raised to its screening in the province by the French consul in Winnipeg, a protest which was rendered redundant by the events of June 1940, of course.

3. Public Archives of Manitba, M(anitoba) F(ilm) C(lassification) B(oard) “Deletions’, 1930-71.

4. A search of election material for 1969 failed to uncover any mention. The writer, a candidate for the New Democratic Party at that time, cannot recall any directive from Central Office alluding to the issues.

5. Report of the Manitoba Censor Review Board to the Hon. Peter Burtniak, Minister of Tourism and Cultural Affairs. Sessional paper No. 7, 5 March 1971, p. 21. Paul Morton, of Odeon-Morton Theatres, figures most prominently among the commissioners and several sessions were held in his Odeon theatre on Smith Street, Winnipeg. By a 3-2 margin, the Board recommended an end to censorship, with Morton and Bowman dissenting.

6. Ibid., p. 5.

7. The actual figures were: Restricted, 128; Adult (not suitable for children), 59; Adult, 87; General, 77. Source: MFCB Report, 1972.

8. Statues of Manitoba, 1972. 21 Elizabeth II, p. 423 et. seq.

9. Legislative Assembly of Manitoba, 4th Session, 29th Legislature, 1972, p. 2881.

10. Ibid., pp. 2882-2883.

11. Ibid., p. 3391.

12. Ibid., pp. 3398-3399.

13. Ibid., p. 3631.

14. MFCB “Deletions” files, 1971-72.

15. Legislative Assembly, supra, p. 3682.

16. Ibid., p. 3589.

17. Ibid., p. 3591.

18. Ibid., p. 4362. This was the final day of debate on Bill 70.

19. Ibid., p. 4364.

20. MFCB “Deletions” file, 1971-72, Bieseck to Mackling, 3 January 1971.

21. John J. Pungente, born Thunder Bay, 1939. Teacher of English and subsequently principal, St. Paul’s High School, Winnipeg. Father Pungente would later act as media education consultant for his order in England.

22. MFCB “Deletions” file, 1971-72. Again, the court took the view that companies had a reasonable expectation that a certificate of exhibition from the Board afforded their pictures some degree of legitimacy and protection against seizure.

23. Ibid., Bieseck to Minister, “Film Classification Board’s supervisory functions” 26 March 1974, p. 2.

24. Ibid., “Confidential Note” (unsigned), 19 April 1974. Several titles thus scrutinized were resubmitted in truncated form and passed, including O, Calcutta! Bieseck had warned Prima Films of possible legal action and sent a copy of the letter to the Minister. Bieeck to Prima Films Inc., 21 February 1973.

25. Ibid., J. Matthews to Barbara Mills, 20 December 1977. The writer, a projectionist at the Venus Theatre on Sargent Avenue, had removed 180 feet of footage from The Bite in seven separate cuts, resulting in a loss of about two minutes’ running time because, as he put it, “I was not satisfied the film met current standards” He also felt it was his civic duty to let the minister be appraised of his action. There is no record as to whether the management was in agreement.

26. The author can speak from personal experience from his tenure on the Board. On many occasions prints had been substantially reduced in running time by the combined action of the Ontario Board of Censors and the distributors. For example, the self-rated XXX, U.S: made Deep Inside Annie Sprinkle had shrunk from 82 minutes to 38 by the time it was submitted in Winnipeg.

27. If there was disagreement, it was usually over perceived leniency by Toronto! The banning, by the Alberta censor in 1963, of the version of Tom Jones which had played, without incident, throughout Ontario was a notorious example. Government MLAs and their wives were given a private screening to prove its unsuitability for the masses.

28. In Winnipeg, three downtown theatres, devoted in whole or in part to the genre, closed their doors permanently in the 1980s. A fourth switched to reruns and is now mostly a showcase for Chinese and other ethnic language films.

Page revised: 22 May 2024