| Index |

|

7.

The Brandon, Saskatchewan & Hudson's Bay Railway

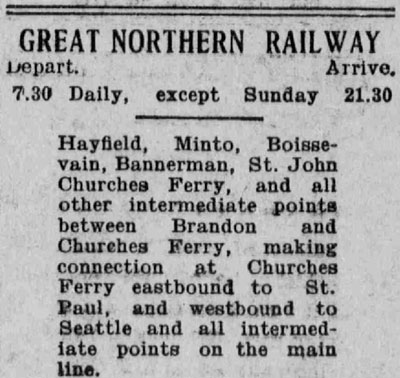

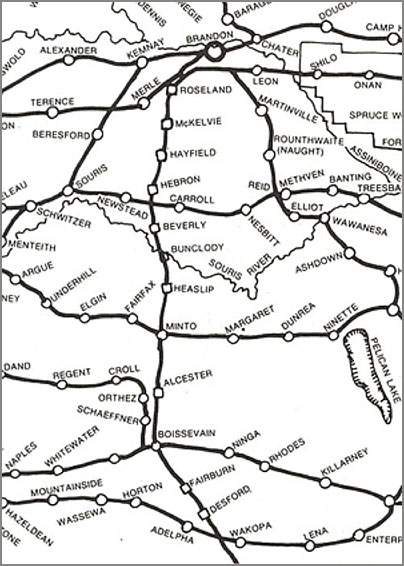

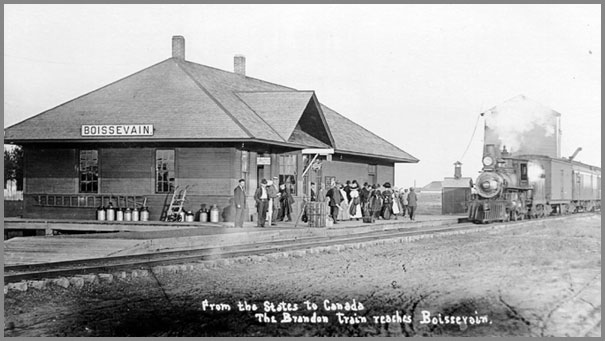

The Wakopa pioneers waited for about twenty-five years to get their railway line. The arrival of the Canadian Northern branch spurred the re-birth of Wakopa as a village and the dust had barely settled on that enterprise when another railway entered the district creating additional transportation options. The Brandon, Saskatchewan and Hudson's Bay Railway, a subsidiary of the Great Northern Railway from the U.S. offered service from Brandon to the small town of St. John, North Dakota where it made connections on the Great Northern lines south to Minneapolis, east to Duluth, and west through Montana to the coast. It was founded by James J. Hill who was born in Ontario. Originally his plan was to build a track all the way to Hudson Bay, but nothing was ever pursued past Brandon.  Brandon Sun, Dec 30, 1907 The line, born as it was in the optimistic times of expansion, was perhaps doomed from the start, but it did have its impact for a few short decades on several communities south of Brandon, and in a limited way, on the city itself. We all know about the importance of the railway in the development of the west. Those two venerable Canadian institutions; Pierre Berton and the CBC, have made it hard to escape the role the building of the CPR played in our history. Railways have been romanticized, eulogized, and demonized, but never ignored. Equally true however, is the fact that in much of rural Manitoba, and across the prairies, the rails are being abandoned, torn up and inevitably forgotten. The railway boom lasted only a few short decades before retrenchment began. For rural communities the presence of a rail link went from being indispensable to being inconsequential in a less than forty years. We had barely completed crisscrossing the land with lines when we began taking them up. Sometimes we built too many. That may well be the case with the much-anticipated route from Brandon south to the U.S. Border, seen at the time as a forward-thinking link with the extensive Great Northern Railway. But to rural people in southern Manitoba at the end of the 19th century, there couldn’t be too many rail lines. Many of the first settlers had waited patiently for the first lines, which in many cases were delayed by the infamous “monopoly clause” in the governments deal with the syndicate that built the CPR. Even after the Greenway government was able to end the monopoly in 1888, many farmers still had a long haul to get their grain to the nearest elevator and many complaints about the service they received, specifically the availability of an adequate number of rail cars in peak periods. Anything that would reduce the length of those trips, plus add an element of badly-needed competition was welcome. It wasn’t just farmers who wanted this railway. There was a lot of boosterism associated with railway building. There was profit to be made in the building of the infrastructure and in the establishment of related services. The arrival of a rail link seemed to secure the fortunes of any small settlement and enhance the prospects of existing towns. This line was destined for a short life span, but in that short time it certainly did provide a much-need service, and made quite an impact along its route. Once the deal was struck the line was started without delay, beginning in 1905, and decisions were made quickly regarding the route and placement of stations. Despite the best effort of the rival lines to stall the establishments of the necessary crossings at Wakopa, Boissevain and Minto, the line worked its way northward at an astonishing pace. Rights of way were purchased. Established communities of Boissevain, Minto, and, of course Brandon would be on the route. New sites of Bannerman, Bunclody, Hayfield and Heaslip were surveyed, although not all developed into villages. A deal was struck with McCabe Elevators for grain handling facilities and Great Northern cash was provided up front to build the twelve facilities. Even the sites of Fairburn, Alcester, Griffin, Healip, McKelvie and Roseland would have elevators, but even in those optimistic times villages were not anticipated. While stations were located at most of the villages even stops that didn't evolve into real villages got waiting rooms complete with pot-bellied stoves. Stops like Beverly (originally called Webster) and Hebron, closely spaced between Bunclody and Hayfield, and known as "sidings", got loading platforms. Several sites had dwellings for section foremen and bunkhouses for crew. Water towers, a vital part of the infrastructure in the days of the steam locomotives, were closely spaced on this line with structures at Bannerman, Boissevain, Minto, the Souris River Crossing near Bunclody, Hayfield and Brandon. Each had a pumping manager in charge. Crucial to the whole operation was a 30 year contract to carry the mail. Post offices were established along the line or in several cases moved to be closer to the line. By 1906 the trains were running, bringing an immediate benefit to local farmers, improved mail delivery, easier access to both Brandon and the point in the US, and a much improved distribution of consumer good into the rural area.  By 1912 railway expansion in the southwest corner was at its peak. This map from 1935 shows elevator locations.  One of the earliest Great Northern trains approached Boissevain Station. CREDIT: Boissevain and Morton Regional Archives.  In 2007 The GN Depot at Boissevain was the last station left standing along the Manitoba section of the line. It had been refitted for use by the Highways Department. It has since been torn down. Building The Line Construction of the track bed began in winter. Teams of horses or mules – approximately 12 teams per mile – were used to pull slush scrapers along where the track would be laid. Men operating each team were paid 50 cents per hour for a nine-hour workday and were also expected to supply their own board and feed their team. Though other railroad companies in the area received grants from the federal government to help with construction, the Great Northern got nothing, planning to service the area without the government's financial involvement. Train Service The first trip from St. John's up the line involved the transportation of coal to Brandon. The first train arrived on December 1st, 1906, though only after being stuck in snow cuts for two weeks. The first passenger train operated on April 24th, 1907, and the line soon became the chief mode of north/south transportation for people, mail and goods to and from Brandon. Oil was hauled using the rail line, and a lot of grain—especially from McCabe elevators, as James Hill was a friend of the owner. The circus train also came over the line on its way to the Brandon Fair, and stories are told of the train chugging past with giraffe necks poking out the sides of cars. A train ran once in either direction daily except for Sundays. The roadbed was of very poor quality and in wet weather – particularly in spring – the track would become too soft to be used and service would halt for a month or two. The village of Bannerman, Manitoba, was the first stop along the line on the Canadian side of the border, and this was the location of the customs office for crossing into Canada. Charlie Bryant The train operator along the GNR line for over 30 years was a man named Charlie Bryant, who was so well known that the rail line got the nickname “Charlie's Train.” A very pleasant and affable man, he was a farmer in his spare time near St. John's, ND, but was never too busy to help out his fellow farmers or extend an extra courtesy to passengers. Charlie had no problem stopping the train between stations to accommodate harvest workers, pick up or drop off passengers close to their homes, or pick up goods. One story that has been handed down concerns a farmer who lived near the tracks. He was threshing and experienced a machinery breakdown. Local dealers didn’t have the part needed, but they were able to have the part sent from Brandon later that same day and the train stopped right by the field to drop it off. Service indeed. The End of the Line The depression in the 1930s brought a reduction in freight and passenger business. The switch from using trains to driving automobiles for transportation began, and in 1936 the Great Northern's mail contract ended. It was not renewed. After this, train service along the GN line ended altogether, and in 1937 the track was torn up.  A GN Crew House does remain in use as a residence in Boissevain, perhaps the last GN related building in Manitoba.  Great Northern Memories In 1905 when the surveying for the Great Northern was done, the railway was to go right through the corner of the Alex Henderson's farmhouse. In 1906, Henderson moved out of his home on 12-2-19 and began rebuilding his entire operation on 13-2-19. The Great Northern crew quickly replaced the house on 12-2-19 with railway track. Although some compensation was given to Mr. Henderson for his loss, it by no means covered the loss suffered by the family. **A thank-you to Mrs. Gertie Henderson for sharing some of her memories. Bill Moncur - on the impact of the line. … of course the grain was a great deal and there was a lot of grain shipped along the Great Northern, all the way from Brandon right through to the boundary went to the States and the service was always a little bit better than what the Canadian companies could produce. And then along with that was the express, that is the cream and eggs that we used to ship down to Devil’s Lake and that was a real boon to the farm people all the way along the line right through to Brandon. That was a daily service that they got, ship the one day, and your cheque came back the next with the cream can. It was really super and you always got a better price down there than what you could get up here. And of course, then there was objection from the Canadian companies, the creameries, but nonetheless as long as the railroad had the service here, the people made use of it. A lot of fruit came up this way too from the States, a tremendous amount of fruit. Oh you mentioned that. I can remember these big deals that they used to ship the bananas, high crates and I happened to be in when the freight came in, you’d see all these things be there, different cases of lettuce and that. |