HOME

1. Introduction

2. Historical Overview

3.

A Scientific Approach: Experimental

and

Demonstration Farms

4. The Greening of the West

by Lyle Dick,

Parks Canada

5. The Lyleton Area

Shelterbelts

6. The Indian Head

Shelterbelt Centre

7. The P.F.R.A

8. The Gerald Malaher

Wildlife

Management Area

9. Arbor Day & Tree Stories

10. Shelterbelts and Modern Agriculture

11. Links & Resources

|

3. A Scientific Approach to

Prairie Agriculture

Dominion

Experimental Farms

Farmers

and agronomists, agricultural institutes and societies,

provincial agricultural colleges, and the federal government each

contributed in the development of effective dryland farming techniques

and the establishment of the Dominion Experimental Farms at Ottawa,

Indian Head and Brandon were and important Federal contribution.

Pressure

to establish a federal agricultural education service had

existed since the mid-nineteenth century. Not only were most recent

immigrants from Europe ill-equipped to deal with the problems of

Canadian agriculture, but

Early in

the settlement era it became obvious that agricultural methods

that travelled with settlers from common in Ontario, Britain, Central

and Eastern Europe were inadequate to the challenge of farming the

semi-arid regions of the prairies.

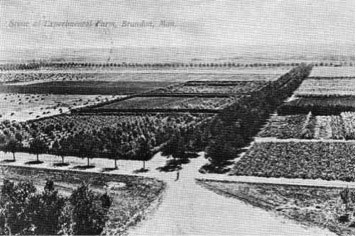

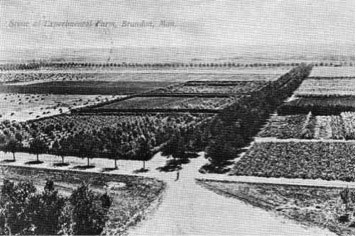

Brandon

Experimental Farm

Brandon

Experimental Farm

In 1885,

the government committed itself to the establishment of

Dominion Experimental Farms in five provinces, and in 1887, one such

farm was established at Brandon. Agronomists at these farms conducted a

great many experiments related to dryland farming.

Research

findings related to comparisons of seed varieties, methods for

summer fallowing, bluestoning and seed drilling made available to local

farmers and inquiries from farmers were diligently answered by the

research scientists.

The

Brandon Farm was just one of a network of experimental farms and

field stations, which included a second Dominion Experimental Farm at

Morden and experimental and demonstration farms operated by the

Manitoba government Agricultural Extension Services and the Manitoba

Agricultural College.

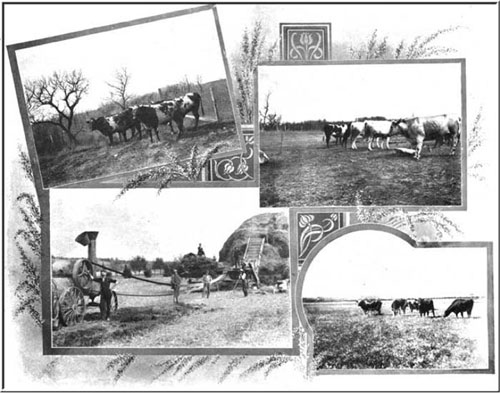

Scenes

from the Brandon Experimental Farm

Illustrated

Souvenir of Brandon, Manitoba :

Published by W. Warner, Brandon : Page 40

Illustrated

Souvenir of Brandon, Manitoba :

Published by W. Warner, Brandon : Page 40

Demonstration

and Reclamation Farms

Killarney

Demonstration Farm

The

Demonstration Farm at Killarney represents on of the Manitoba

government’s efforts in agricultural research and education. It was

established when George Lawrence, a Killarney pioneer, was Manitoba’s

minister of agriculture. The purpose was to identify and promote

farming practices and crop varieties suited to this particular region

of the province.

The

demonstration farm was closed in 1946.

Melita

Demonstration Farm 1913 (From “Our First Century”)

November

6: Mr. S. A. Bedford, Deputy Minister of Agriculture in the

Manitoba Government was in town last week and located a government

demonstration farm in this district. It will be on the Fred Merret farm

west of town and will face the main road. Forty acres just west of the

house was secured. Mr. Bedford expressed himself as highly pleased with

the location believing that he had secured a fair average of the soil

in the district.

Mr.

Bedford said the plan of the government was to carry out at small

cost, demonstration plots at various places in the province. The land

will be divided into five acre plots and under a system of rotation of

crops will be cropped every year. Experiments are to be carried on with

fodder and root crops. Work on the plots will be done by the resident

farmer under instructions from Mr. Bedford. Mr. Bedford, who for 18

years was superintendent of the Brandon Experimental Farm, and who also

is a close student of agricultural life is undoubtedly the right man in

the right place as Deputy Minister of Agriculture in this western

province. For 30 years Mr. Bedford has studied conditions in the west.

He is a firm believer in mixed farming as he points out one of the

things which the demonstration farm will demonstrate will be the manner

in which stock feed can be grown without diminishing the wheat product.

To Mr. Lyle is due much of the credit for the establishment of this

farm in this constituency.

Mature

shelterbelts, north of Melita

Mature

shelterbelts, north of Melita

Melita

Reclamation Farm

(From “Our First Century”)

The

Dominion Department of Agriculture (1935-1960), leased N 19-4-26, S

30-4-26 and 29-4-26 just north of Melita to experiment in reclamation

of lands abandoned, and to determine the best cultural practices and

cropping methods to prevent further serious drifting.

Mr. H.

A. Craig B.S.A., a graduate of the University of Manitoba

drafted plans and Mr. J. Parker resided at the station to be in charge.

History

of the Reclamation Station Melita (From “Our First Century”)

Ken

Dawley

from Melita Tails & Trails

The

Reclamation Station, Melita, Manitoba, was established in 1935

under provisions of the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Act investigating

problems associated with drought and wind erosion in the Souris River

basin. Large tracts of land in southwestern Manitoba had been

devastated by wind and wide areas were denuded of their vegetation.

Over wide areas, the topsoil which contains the natural fertility for

crop production, was removed to varying degrees leaving exposed an

infertile subsoil which during periods of below average rainfall is

capable of supporting meager crops. The site chosen for the Station is

representative of the extensive area which has been severely eroded by

wind. The Reclamation Station is operated as a substation and is

supervised from the Experimental Farm, Brandon.

Early

observational investigations disclosed that, while the sandy

nature of the top soil had a low water retention capacity as compared

with the clay soils of the Carroll Clay Association or the Red River

Valley soil types, ground water levels were relatively close to the

surface. This indicated that forage crops such as brome grass, crested

wheat grass, alfalfa and sweet clover would supply hay and pasture for

livestock because these crops were capable of sending down root systems

which would feed from the natural water table. At that time, it was

postulated that trees would flourish in the region, provided they could

be kept free from insects and disease. With these two important factors

in mind, a basic plan was formed for the stabilization of soils in

southern Manitoba.

The

initial work undertaken included land levelling, the stabilization

of drift soil by seeding grasses and legumes, fall rye and other crops

and tree planting. During the ensuing years, the experimental work has

been extended to include a wide field of crop production. The Station

now includes 1440 acres of rented land. The need for including

livestock in the reclamation program became evident and in 1941 a

portion of the purebred Shorthorn herd from the Experimental Farm,

Brandon, was transferred to Melita. The feeding of steers, heifers and

bulls on an individual basis as part of the sire testing program had

been underway for four years.

Meteorological

data have been recorded at the Reclamation Station since

1937. This data includes temperature, precipitation, wind velocity and

in recent years, evaporation from a free water suface. This information

had been useful in relating crop production to climatological phenomena.

The term

reclamation implies that waste and is being brought under

cultivation. The problems associated with such a program are many, and

the final solution to a successful conclusion of the program is often

hampered by factors not anticipated. Soils are composed of great hosts

of living things and in the application of certain tillage practices or

certain fertility treatments, the balance in population of soil fauna

may be changed thus giving rise to poor crops of low quality. The

problem of restoring fertility to soils which have been severely

damaged by wind erosion is of major concern. The use of soil building

crops such as grasses and legumes has been an important measure in land

reclamation. The application of rotted manure, the growing of green

manure crops such as sweet clover and the application of various

chemical fertilizers are being investigated. The process of rebuilding

a soil which has suffered from erosion is slow as measured by periods

of time and thus long term fertility experiments provide valuable

sources of information.

The

importance of tillage machines cannot be overlooked in a program of

soil reclamation and soil protection. The vulnerability of light

textured soils to erosion by wind has brought about the improvement in

tillage techniques. Trash land farming or the maintenance of the trash

or previous crop residue at or near the soil surface should largely

replace black summerfallows. While this trash farming procedure is the

desired method for soil protection, factors such as weed growth often

limit the extent to which trash farming can be carried out

successfully. The tendency has been to kill weed growth as soon as

sufficient populations have developed over a field and with successive

tillage operations. More of trash is buried each time until by the

completion of the fallow season, all trash has disappeared. The

limiting factor in trash farming seems to be the low organic matter

content of the soil. The rate at which this material dissapears when

incorporated below the soil surface is extremely rapid under Melita

conditions. The reason for this taking place seems to be that the soil

population of micro-organisms are so hungry for food that when amounts

of organic matter in the form of crop residues are added, they are

rapidly consumed, thus leaving a soil low in organic substances.

The

testing of cereal and forage crop varieties constitutes an

important phase of the experimental work at Melita. The performance of

these crops is often quite different from other points of testing in

the province and the information obtained serves as a basis for

recommendations to farmers of the area. From time to time, new

varieties of grain are increased at the Melita station for distribution

to local farmers on a registered or certified basis.

The

annual Field Days which are held serve as an important method of

circulating information which has been compiled at the Station. Local

press releases and bulletins covering recommended cereal varieties and

cultural practices appear from time to time. Letters, phone calls and

personal visits of farmers and others to the Station serve as a

yardstick to measure the interest which is being taken in the affairs

of the Reclamation Station, Melita.

Reclamation

Station Beneficial to District

by

Murray Parker (son of J. Parker) March 28, 1946

Ten

years ago, the land that is now the Dominion Reclamation Station,

was chiefly sand banks, Russian thistle and ragweeds. What is now the

green lawn was then tree-like weeds extending to eight feet in height.

Sand was piled high over the fences, making ridges which are still

visible. In the field, holes were gouged and sand piles formed only to

be shifted again by the wind. When one looked at the fields, it seemed

a futile task to make this arid land productive of crops again.

In 1936,

a quarter section was enclosed by three rows of trees and

three intersectional hedges. When trees were planted, windbreaks had to

be built of weeds and old sweet clover to keep the sand from cutting

off the delicate young trees. Today these trees have attained a height

of 25 feet, forming an excellent windbreak, and beautifying the farm to

a large ex- tent. During the growing season, these trees are of

particular value, in protecting the sprouting plants and helping to

prevent soil drifting, as they are now of sufficient height to reduce

the wind velocity. In winter the trees collect a large amount of snow,

and this extra moisture is bound to be beneficial to adjacent crops.

As each

quarter section of the farm varies from the others, there is

considerable difference in soil, thus different experiments are carried

out on each. The only land that was safe from wind erosion, was land

which had couch grass. One quarter section in particular, was solid

couch grass, but in the past few years this land has been brought into

production, producing real good crops during favourable seasons.

The

method of couch grass eradication has been a combination of the

stiff tooth cultivator, with narrow points and the one-way disc. After

about three cultivations it was found necessary to go over the field

with the one-way disc to chop the clumps of sod and grass roots. It was

found necessary to watch the new growth of couch grass very closely. In

this sandy loam soil, all that seems necessary to kill the couch grass,

is to open the soil, with cultivation letting the air in to dry out the

land and the roots. In a wet season the cost of couch eradication is

almost doubled compared to that of a dry season. Another important

factor in the eradication is to work only the acreage that can be

properly handled by the equipment available during the season.

In the

growing of grain crops in this light sandy loam soil it has been

the practice on the Reclamation Station to strip farm, this way that

soil drifting is more easily controlled. Observations for the past

eight years have revealed that, on days when soil drifting was

prevalent, the wind blew from the northwest. The next highest wind came

from the southwest. It would appear then, the strips should be north

and south.

Besides

strip farming, trash covers have been found very effective in

controlling wind erosion. Sufficient trash must be left on the surface

so as not to be buried by successive tillage operations. Results for

the past nine years show little difference in yield or cost of

production from the ploughed areas in comparison with the

surface-worked fallows. The main advantage of surface tillage is the

protection it gives to the soil.

On soil

such as we have in this district and that farmed for as long as

it has been, the time has come to begin seeding a portion of the land

down with grasses and legumes. It would appear that this could be

worked in with crop rotation system. There is no doubt the soil is in

need of fibre and organic matter, to get results the fields or portion

thereof should be left in grass at least three years. At present on the

station there are 240 acres of the 1120 acres seeded down to grasses

and legumes.

Since

the time of its opening, the Reclamation Station has set a fine

example of what can be done to otherwise useless land. It has also

rendered valuable service in the form of expert advice and suggestions

on various farm problems. It is to be hoped that in future years this

station will continue to show good results, thereby setting an example

of Canadian progressiveness in the agriculture field.

Herb

Edgar Family History

(Edward History Book)

Edgars

operated a mixed farming operation on the farm north of Lyleton,

28-1-28

The

Edgar farm was selected by the Brandon Experimental Farm as a

sub-station in 1935 to record cost of production, rotations, and test

plots of new varieties of grain, with yearly field days held on the

farm to view the year's work. This project was under the direction of

M. J. Tinline and D. A. Brown. Herb also recorded the rainfall and

snowfall from 1935-1970. In 1960 the Experimental Farm changed the

substation to a Research Station with more emphasis on plot work,

varieties and yields. The contract was terminated in 1970.

Lyleton

Sub-Station by G. H. Edgar (Edward History)

Soil

Drifting was a big problem in the early thirties due to the

drought and the grasshoppers, leaving very little stubble or trash in

the soil. About the only thing that would grow was the Russian thistle

which was cut and put up for feed.

In 1934,

the federal government under the P.F.R.A. (Prairie Farm

Rehabilitation Act) decided to set up a series of sub-stations in

Western Canada to control soil drifting by strip farming and other

cultural methods.

Under

the Brandon Experimental Farm with Su-perintendent Mr. M. J.

Tinline and Mr. D. A. Brown, section 28-1-28 was selected as the site

for the Lyleton sub-station. The south half of the section was owned by

Herb Edgar and the north half was owned by Jack Parsons. A supervisor

was selected by the Experimental Farm to work with the operators of the

sub-station. Mr. A. W. Wilton was the first permanent supervisor.

The

owners received a rental for the land as well as grass seed and

some seed grain from the government.

The

fields were laid out in strips from 200 feet to 400 feet wide

depending on the texture of the soil, favoring a north-south direction,

as the strong prevailing winds were west-northwest and south-east.

The

owners were encouraged to be mixed farmers with cattle, hogs and an

approved number of hens, as well as to have a large garden, flowers,

and shrubs. Fruit trees were supplied from the Morden Experimental farm.

Under

their supervision, a large shelterbelt of trees including

evergreens were planted around the buildings with a tree-lined roadway

to town.

A test

plot of all varieties of grain and flax was planted each year.

These plots were harvested and recorded by the Brandon Experimental

Farm for yield and performance under the local conditions and results

published in book form of all sub-stations in Manitoba.

In 1936,

the Lyleton Tree Field Shelterbelt Association was formed, but

the operators of the substation were not allowed to plant trees in the

fields as the government wanted to demonstrate that soil drifting could

be controlled by strip farming and cultural methods. However, in 1950,

under pressure from the operators the government relented and allowed

us to plant field tree shelterbelts.

In 1940

and later, after the yard was landscaped and the farm

shelterbelt was established, the super- visor with the owners set up a

large tent and a Field Day, with speakers from the Experimental Farm to

show and review the different projects, rotations and plots with the

new varieties.

Records

of cost were recorded on all fields, including time, gallons of

fuel, and the implement used.

Precipitation

records were recorded by the opera- tors and sent to

Brandon each month.

In 1960,

the federal government changed the substations to research

stations with emphasis on weather and plot work of all varieties of

wheat, barley, oats, flax and soybeans. This contract was terminated in

1970.

C.P.R.

Demonstration Farm

(From the R.M. of Edward History)

When the

village of Pierson was settled on the north side of the

correction line, and the railroad came through, the townsite was all

used for dwellings and business establishments such as: the lumberyard,

hardware, two general stores, schools, churches, implement dealers,

elevator and rink. As more room for expansion was required, it was

therefore decided to purchase more land from the C.P.R. Company, in

order to expand on the south side of the correction line.

In 1912,

the C.P.R. Company decided to develop a Demonstration farm and

so built up a full line of modern buildings, including a two-story

cottage roof house, size 28 by 28 feet. The lower story was covered

with white siding, the second story with green shingles as was the

cottage roof. The house contained four bedrooms, three clothes closets,

and an upstairs hall. The downstairs consisted of a living- room,

bedroom, hallway, kitchen and pantry. There was a small excavation

under the main floor that served as a storage cellar.

The out

buildings consisted of an outside toilet, granary, pig house,

hen house and a dairy building for the cream separator and churn, with

a wash up space. There was a modern-type barn with a loft and storage

space in the centre of the barn. It had a high roof and on the west and

east side were lean-tos with the mangers along the outside of the

middle hay shed. Facing towards it was a shed for horses and one for

cattle, especially the milk cows and cow and calf crop.

In 1912

the C.P.R. Company went all out to fix the portion remaining of

the N 35-2-29 for their demonstration farm; crews were hired to fence

and cross fence with pagewire. Mr. Irwin Eyers of Gainsborough was

hired with his big steam-powered engine and ploughs to break the sod.

Buildings were erected and painted. Plots for experimental work were

planned and things were put into shape to carry on.

The fall

of 1913 Mr. J. Mates and his wife, from Butterfield, moved

from their farm and took up residence in their new place as manager of

the C.P.R. Demonstration farm. This involved a lot of work keeping

records and farm data, so Mr. George Followell was engaged to help Mr.

Mates.

When Mr.

Mates came to the farm, he sold some of his equipment to the

C.P .R. One team I remember was a pair of brown mares, almost identical

mates, called Gypsy and Nellie.

This

went along well until 1916 when Jack enlisted in the 222 Battalion

and his wife and little son went to Scotland to her parents, where a

second son was born and Mrs. Mates passed away.

When

Jack enlisted, Mr. Hogg, wife and family came to operate the farm.

In 1918

the farm was sold to Mel Mayes, but he gave it up.

|