HOME

1. Introduction

2.

Historical Overview

3. A Scientific Approach: Experimental

and

Demonstration Farms

4. The Greening of the West

by Lyle Dick,

Parks Canada

5. The Lyleton Area

Shelterbelts

6. The Indian Head

Shelterbelt Centre

7. The P.F.R.A

8. The Gerald Malaher

Wildlife

Management Area

9. Arbor Day & Tree Stories

10. Shelterbelts and Modern Agriculture

11. Links & Resources

|

2. Historical Overview

Since

the days of the first agricultural settlements on the prairies

began trees have been an issue. To a generation whose parents toiled at

removing trees from Ontario farms to make way for productive crops, the

first glance at the treeless expanse of southwestern Manitoba was a

revelation. They saw immediately the ease with which they could

transform the grassy plain into orderly fields of cereal crops. No

backbreaking hours felling the trees, and fighting with the seemingly

endless stumps and tree roots that were left behind. Just plow and

plant!

Of

course they needed trees for fuel and building supplies, but as long

a the homestead was within a reasonable distance from the wooden

valleys of the rivers or the heavily forested Turtle Mountains, most

preferred a flat quarter section with an unbroken horizon.

And that

worked, for a while.

There

were quite a few things about this land that the first settlers

didn’t know.

They

didn’t know that this productive land, which at first glance

looked so fertile, existed in a fragile balance. The often-repeated

story was of the profusion of wild strawberries, so thick that the feet

of the oxen were stained red. What wasn’t told was that the succession

of wet years in the early 1880’s was not necessarily a permanent state

of affairs.

They

didn’t know that the treeless prairie was treeless, not because it

wouldn’t naturally support such growth, but because the ever-present

prairie fires struck saplings down before they had a chance to get

started. Where trees were established, along streambeds and in hills,

the retention of moisture that they fostered was the defense against

the fires. They would figure this out before long.

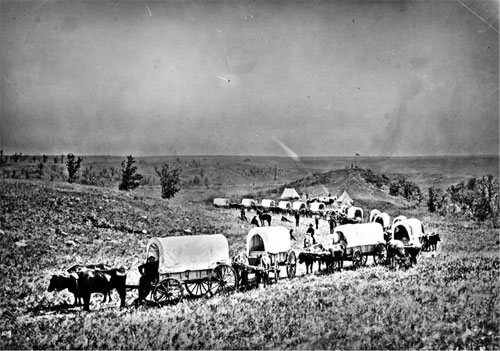

The

Boundary Commission travels through a dry and

treeless southwestern

Manitoba in 1873

The

Boundary Commission travels through a dry and

treeless southwestern

Manitoba in 1873

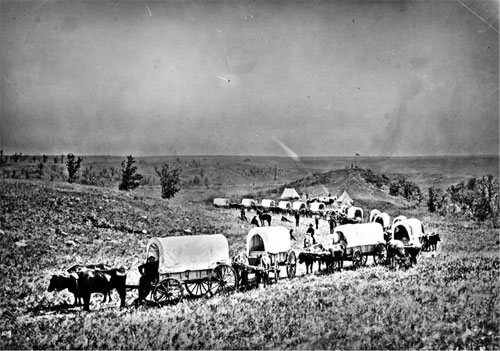

Tree

planting initiatives were evident in all early prairie villages.

Lauder Mb.

Tree

planting initiatives were evident in all early prairie villages.

Lauder Mb.

|