|

Technology

|

|

The

Evolution of the Camera

A

Short History Of Photography (Adapted from Wikipeida)

In

almost 200 years, the camera developed from a plain box that took

blurry photos to the high-tech mini computers found in today's DSLRs

and smartphones.

The

First Permanent Images

Photography,

as we know it today, began in the late 1830s in France. Joseph

Nicéphore Niépce used a portable camera obscura to expose a pewter

plate coated with bitumen to light. This is the first recorded image

that did not fade quickly.

Niépce's

success led to a number of other experiments and photography progressed

very rapidly. Daguerreotypes, emulsion plates, and wet plates were

developed almost simultaneously in the mid- to late-1800s.

Niépce's

experiment led to a collaboration with Louis Daguerre. The result was

the creation of the daguerreotype, a forerunner of modern film. A

copper plate was coated with silver and exposed to iodine vapor before

it was exposed to light.

To

create the image on the plate, the early daguerreotypes had to be

exposed to light for up to 15 minutes.

The

daguerreotype was very popular until it was replaced in the late 1850s

by emulsion plates.

Emulsion

Plates

Emulsion

plates, or wet plates, were less expensive than daguerreotypes and

required only two or three seconds of exposure time. This made them

much more suited to portrait photographs, which was the most common use

of photography at the time. Many photographs from the Civil War were

produced on wet plates.

These

wet plates used an emulsion process called the Collodion process,

rather than a simple coating on the image plate. It was during this

time that bellows were added to cameras to help with focusing.

Two

common types of emulsion plates were the ambrotype and the tintype.

Ambrotypes used a glass plate instead of the copper plate of the

daguerreotypes. Tintypes used a tin plate. While these plates were much

more sensitive to light, they had to be developed quickly.

Photographers needed to have chemistry on hand and many traveled in

wagons that doubled as a darkroom.

Dry

Plates

In

the 1870s, photography took another huge leap forward. Richard Maddox

improved on a previous invention to make dry gelatine plates that were

nearly equal to wet plates in speed and quality.

These

dry plates could be stored rather than made as needed. This allowed

photographers much more freedom in taking photographs. The process also

allowed for smaller cameras that could be hand-held. As exposure times

decreased, the first camera with a mechanical shutter was developed.

Cameras

for Everyone

Photography

was only for professionals and the very rich until George Eastman

started a company called Kodak in the 1880s.

Eastman

created a flexible roll film that did not require constantly changing

the solid plates. This allowed him to develop a self-contained box

camera that held 100 film exposures. The camera had a small single lens

with no focusing adjustment.

The

consumer would take pictures and send the camera back to the factory

for the film to be developed and prints made, much like modern

disposable cameras. This was the first camera inexpensive enough for

the average person to afford.

The

film was still large. It was not until the late 1940s that 35mm film

became cheap enough for the majority of consumers to use.

Photographic

Equipment in the 1850’s

Humphrey

Lloyd Hime brought his full kit with him to document the Hind

Expedition. His camera had a two inch portrait and a two inch landscape

lens. The rest of his supplies, including chemicals, containers, etc.,

conformed to the requirements listed in Hardwich's Manual of

Photographic Chemistry, a copy of which he carried with him. This

served as a basic guide offering complete instructions on the practice

of wet plate photography.

Collodion

wet-plate photography was the process of both the portrait and

landscape photographer of the 1850s. For landscape photography it

produced some spectacular results, but required a lot of bulky and

cumbersome equipment and supplies. The portable darkroom had to be

right there, because the whole process had to be done while the

collodion was still wet. The most common portable darkroom was some

sort of collapsible tent and pole structure that could be assembled or

dismantled in a few moments and carried on a man's back with little

inconvenience.

To

use the darkroom the photographer put the top part of his body through

the opening and had the cord tied tightly around his waist while his

arms and upper part of his body remained free to move about within the

tent.

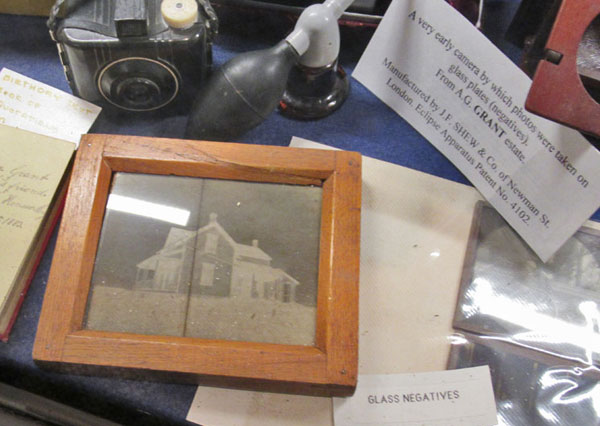

Glass

plates were used in a variety of sizes depending upon the

specifications of the camera and the lens systems employed. For field

work the supply of glass plates was normally carried in a grooved

wooden box. This box would be placed carefully close at hand near the

darkroom tent.

The

camera with its lens would be set up on a sturdy wooden tripod.

When

the plate was well cleaned and polished it was coated with the

photographic collodion emulsion which was the vehicle for retaining the

sensitive silver salts.

The

coated plate was now ready for sensitizing in the Nitrate Bath - a

combination of Silver Nitrate and cold water. The Nitrate Bath could

also be prepared in advance and stored in a bottle. However, the Bath

was sometimes a problem for the landscape photographer as it decomposed

when agitated in transit.

To

sensitize the plate the field photographer had to use his darkroom

tent. It took great care as the solution was corrosive and caused bad

staining. The plate was sensitized in the Bath for varied lengths of

time depending upon the weather - in hot temperatures thirty to forty

seconds - in cold one to five minutes. The sensitized plate was removed

from the Bath, allowed to drain and placed in a clean, dry dark slide

ready for carrying to the camera.

The

photographer gently rested the dark slide with its sensitized wet-plate

on the ground in a shaded area. He then made the final adjustments to

his camera and lens. Removing the lens cap and throwing the focusing

cloth over himself and the back of the camera, the photographer peered

through the ground glass and adjusted his focus, aperture and camera

angle. Satisfied that all was in order he inserted the dark slide with

its plate in the camera. He then made the exposure.

Exposures

for wet-plates were relatively long. For example:

thirty

seconds for a distant view with sky and water

three

minutes for a near view well lighted

six

to ten minutes for interior views

six

to ten minutes for forest scenery with light from above.

Development

as soon as possible after sensitizing and exposure was preferable.

It

was an exacting operation. The exposed plate was removed from the dark

slide. The Pyro-Gallic solution was poured evenly on the plate held in

the hand. Moving the plate to keep the solution moving, the

photographer closely watched the development for thirty to forty

seconds until the image appeared sufficiently

intense.

Knowing the exact development time was mainly a matter of experience.

The

plate could now be brought out of the darkroom tent for further

processing.

Fixing

the negative plate to render the image indestructible by light was the

next operation. The photographer poured t as substance called Hypo on

and off the plate until all the excess iodide was cleared away. The

Hypo was then washed away. This final washing was best done over a

three to four hour period, changing the water several times. Once

assured that all the Hypo was removed the plate was then placed in the

sun or some heated area to dry.

It

was an exacting operation requiring definite skill and artistry, a

goodly amount of physical stamina and energy, sufficient time, and not

a little good fortune in terms of weather, climate and environment.

https://www.thesprucecrafts.com/brief-history-of-photography-2688527

https://www.cameraheritagemuseum.com/cameras

Local

museums feature displays

tracing the evolution of cameras.

Local

museums feature displays

tracing the evolution of cameras.

An

example of a glass-plate negative from the Elgin Museum

An

example of a glass-plate negative from the Elgin Museum

|

|

|