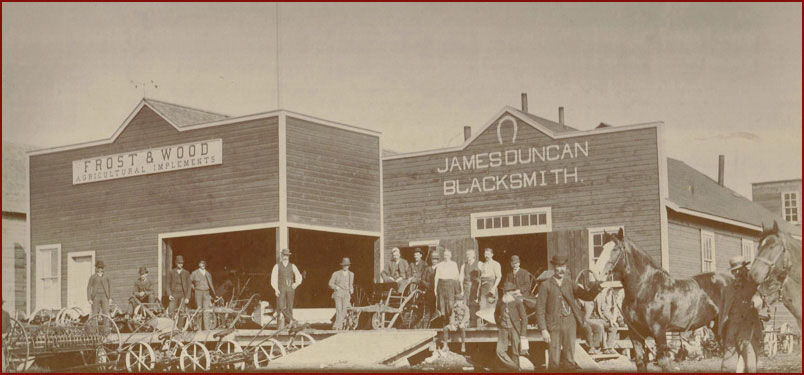

James Duncan was born in Aberdeenshire,

Scotland in 1857, the son of James and Jane (Dalgamo) Duncan. Mr.

Duncan came to Canada in 1882 where he met Miss Helen McGuire, formerly

from England. They were married in Moffat, Saskatchewan in

1887. He homesteaded in Wolseley, Saskatchewan (N.W.T.) and also served

in the North-West Rebellion in 1885.

In 1888, Mr. Duncan settled in Melita. He worked at his blacksmith

trade before the town was incorporated. Later he established a farm

implement business and he was also associated with insurance.

Soon after the incorporation of Melita, he served on the town council

and rendered the community excellent service in this capacity. In other

ways he devoted his energies to the development of the town and

district. He was a member of the board of trade for many years and his

work as such, was recognized by his associates, who elected him to the

presidency.

He was a justice of the peace under the Greenway Government.

Mr. Duncan linked up with the I.O.O.F. in the early days of his career.

He was past noble grand of Melita Lodge No. 20, past grand master, and

past grand representative, attending the Grand Lodge at Atlanta,

Georgia, Indianapolis, Indiana and Winnipeg, while he was also past

chief patriarch.

Adapted from Our First Century, page 520

Photo from the Manitoba Archives

A Day in the Life of a Blacksmith

For the early settlers, the blacksmith was perhaps the most essential

tradesman. Not only did he make the iron parts for the

first farming implements, he also could repair all iron objects by

hammering them by hand on an anvil.

After heating the iron until white-hot, the blacksmith would then shape

and wield a multitude of objects from it, including

carriage bolts and wheels, iron work, cooking utensils, and most

importantly, horseshoes.

Blacksmiths who made horseshoes were called farriers, derived from the

Latin word for iron. At a time when horses were the

only means of transport, the blacksmith was important to not only

individual farmers and travelers. but also to merchants

whose businesses depended on transporting their goods to other places.

Also, because they spent much of their time shoeing

horses, blacksmiths gained a considerable amount of knowledge about

equine diseases.

The new industrial output of the late 1800s allowed the smith to

improve his shop. With a small boiler, steam engine, and a

system of overhead shafts, pulleys, and leather belts, the formerly

hand operated shop equipment like the post drill, the

blower, and other equipment could he easily powered. The small belt

powered machines like the Little Giant trip hammer

or its blacksmith built counterpart took its place in many small shops.

Later, the "steam" part of the steam driven leather belt

systems were replaced with small gasoline engines or electric motors.

In time, many power hammers were fitted with their own electric motors.

Many blacksmiths were manufacturers as well. Wagon boxes, the setting

of wagon and buggy tyres, lathe

turned parts for spinning wheels, the single bob manure sleigh, the

making of sleigh runners, bolsters, bunks and

tongues, and the custom manufacture of truck transfer boxes with cattle

hauling equipment were some of the items fabricated with finesse

befitting the labourers. Always, along with the aforesaid, there were

the innumerable interruptions to repair broken machinery as is wont to

happen in a mixed farming area.

|