Pre-Contact, Aboriginal and First Nations

Memoirs of an Indian Police Scout By S/Cst. Paul W. Fox

RCMP Quarterly October, 1947 p. 162 - 169

| Proud of his part in upholding the

law, the author who is over 70 years old and soon to be retired as an

Indian Police Scout, looks back on pleasant memories of his long

association with members of the Mounted Police and of his travels in

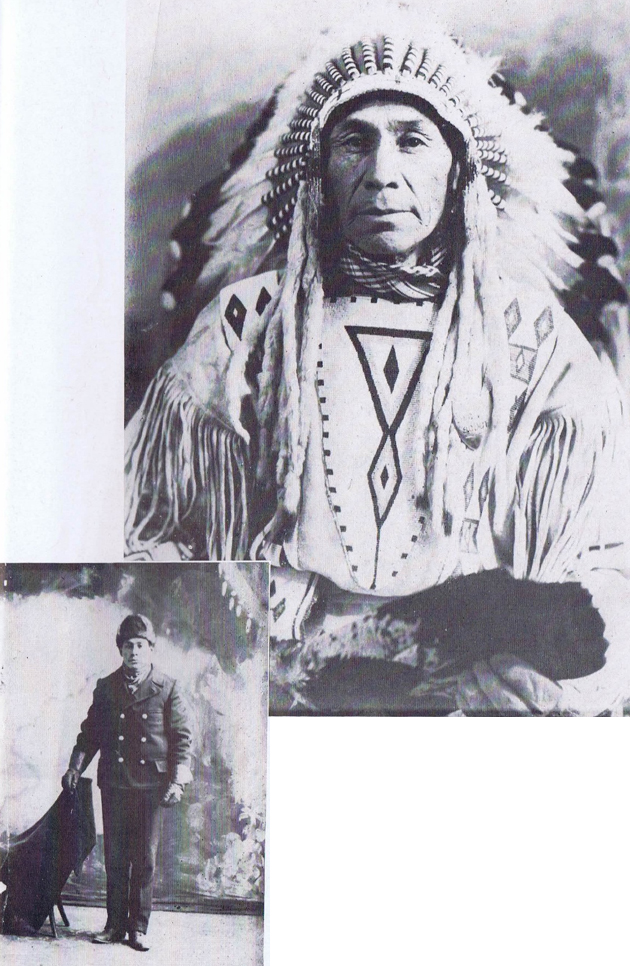

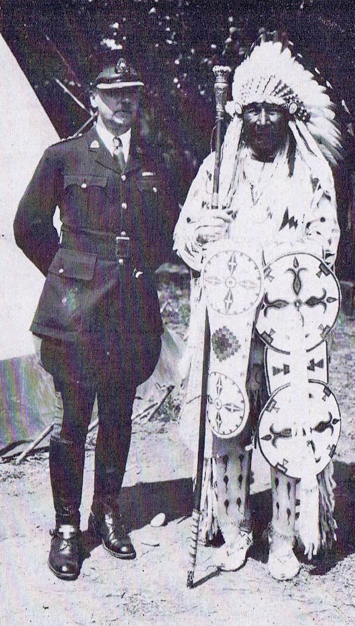

their company. The earliest part of my boyhood that I remember was spent with my mother and grandparents, in the Cypress Hills near old Fort Walsh. Camped nearby were a large band of Cree Indians and some Saulteaux and Assiniboines under Poundmaker, Chiefs Big Bear, Little Pine and others whose names I have forgotten. As a boy playing among the teepees, I grew accustomed to seeing members of the North West Mounted Police, and looked on in awe as they performed mounted and foot drill in their full dress uniforms or rode through the camp on duty. I seem to recall that on occasion my mother warned me if I wasn’t good “the shemagonis will get you” – but as children are learning in Canada today through the Force’s Youth and Police Movement I learned that the police were friends, and a youthful ambition was fulfilled later when I engaged in the Force as a scout. Buffalo Coat, my father, was a noted warrior and chief of the Wandering Crees. He died at Chester, Mont., U.S.A., in 1909. I was born in the Little Mountains east of Fort Benton, Mont., in the spring of 1876, and was five years old when I arrived at Fort Walsh with Iron Lodge, my mother. The government had already started moving the Indians from the Cypress Hills to the reservations that had been set aside for them. The large group was broken up, and most of them were taken north by the police. One chief and his band remained, however, and to this day some of that tribe which is known as the Rabbitskin Crees dwell in the Cypress Hills. When the bands were breaking up, Chief Crowfoot of the Blackfoot paid a farewell visit to his adopted son, Poundmaker, and it so happened that he invited my grandfather, Talking Crow (Ka-ka-Kiw-Bo-No-Tow), to go and live with the Blackfoot at Blackfoot Crossing. Accordingly in the summer of 1883 my grandfather and a few other Crees including me left the Cypress Hills, travelled along the new railroad to Medicine Hat, then north-west to Cluny and on to the Blackfoot Crossing where we were all admitted to the Blackfoot tribe by Crowfoot and other chiefs.  Top: The author in Indian dress.

Bottom: Special Constable Fox

in his younger days, attired in the garb of an Indian Police Scout.

The arrangement was a rather odd one so far as my grandfather was concerned, for in his youth he had been a deadly enemy of the Blackfoot. Many times as a lad I listened to his tales of daring – horse stealing at night, forays and mounted skirmishes against Blackfoot braves who named him “The Stealer.” However, before the police arrived in the West in 1874, the Crees and Blackfoot entered into a treaty as a result of which my grandfather became a warrior for the Blackfoot and many times led them on the war-path against the Crows. I stayed with my grandparents at Blackfoot Crossing until the autumn of 1884 when my mother and I moved to Calgary to live with my uncle, William Gladstone, who was interpreter for the N.W.M.P. Next year, when The Northwest Rebellion broke out, we and certain other Crees were assigned to the area now known as Victoria Park, Calgary, Alta., and kept under close observation. In 1886 my mother died at Shagganapi Point – present-day site of the Calgary municipal golf curse. Before the year ended, another uncle, Crow Child, took me to the Sarcee Reserve where I remained with him until the autumn of 1887 at which time I returned to live with my grandparents at Blackfoot Crossing. Two years later I attended St. Joseph’s Industrial School near Dunbow. Here though Silver Fox, my birth name, was changed to Slattery (the name given to my elder brother who had preceded me to the school), I continued to be called “Fox” both by the staff and my chums. * * * After 11 years at the school I was engaged in the spring of 1900 by the N.W.M.P. as an Indian Scout, succeeding Neil Yellow Wings at Pincher Creek. In July or August of that year I was transferred to “D” Division, Macleod, as interpreter. Supt. J. Howe was O.C. and Inspr. J. A. McGibbon (Ot-Sk-Us-Ki – Blue Face) father of present Supt. D. L. McGibbon (Ee-Ni-Po-Ka – Buffalo Child) served under him. I was also interpreter for “K” Division, Lethbridge, where the O.C. was Supt. R. B. Deane (Ah-Po-Yi-Is-Tu-Yiw – Fair Mustache). Superintendent Howe died in 1902 and was succeeded by Inspr. P. C. H. Primrose (Ma-Ni-Ka-Pi-No – Young Bachelor Chief), who had just come down from the Yukon. Inspr. C. Starnes (Su-ka-Pis-Siw – Short Legs) was there as well. I was re-engaged in the autumn of 1903, and in the spring of 1905 left southern Alberta for Gleichen on the Blackfoot Reserve further north. Two years later my services were requested at “E” Division, Calgary, to which point Superintendent Deane had in the meantime been transferred at as O. C. Inspr. G. E. Sanders (Ah-How-Ki-Sa-Ko-Ka-Da-Bi-Ni – Man With One Eye-glass) was with him. After about six months or so I took my discharge. Re-engaged in 1908 at Standoff, I was shortly afterwards transferred to Cardston Detachment where I served as Indian scout and interpreter until the summer of 1910. On Mar. 24, 1924, I succeeded Vincent Yellow Old Woman as Indian Scout for the Blackfoot Reserve and served there until 1928. The Force was then known as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, so that I have served in the N.W.M.P., the R.N.W.M.P. and the R.C.M.P. the detachment which policed this reserve was at Gleichen, and a few years later Sgt. B. Tomlinson (Ik-Ka-Nik-Stus-Sto-Ya – Long Mustache) was in charge there. In 1933 I was re-engaged as Indian Scout and again attached to Gleichen. Cpl. D. G. Ashby (Kus-Kis-Ta-So-Ka-Si-My – Beaver Coat) was in charge of the detachment from 1935 to 1942, since which time I have been working for Cpl. F. A. Amy (Ki-Yo-Ko-Os – Bear Child). As Indian scout and interpreter I have served under Commissioners Herchmer, Perry, Starnes, MacBrien and the present Commr. S. T. Wood. While I have not worked on any murders or cattle rustlings, back in 1902 I helped round up some Blood Indians who had stolen horses in the Cardston District. About 80 head of horses had been sold by these thieves to a man south-east of Pincher Creek. The investigation was complicated by the fact that all the rustlers had assumed false names, such as Dog in The Shade, White Calf, White Cap, Good Rider and White Horse. But fortunately the man who bought the stolen stock was very observant and had taken special notice of the horse traders and marked down their names. I assisted the police considerably for with the accurate descriptions and my knowledge of the Indians I was able to identify the guilty men. For instance the buyer had said that one of the traders had very fat puffy eyes, a round face and had given his name as “Dog in The Shade.” I knew at once that Percy Steele, an Indian with whom I had gone to school, answered that description. Steele’s English was poor, and when the buyer asked him for his name he attempted to give that of Duncan Shade, another Indian whom he knew. However, the buyer misunderstood him and marked him down as “Dog In The Shade.” Another of the culprits, who had given his name as White Cap, was described as having a squeaky voice, a long nose, and big thick lips. I immediately identified him as Hungry Crow. As leader of the gang Crow got three years in Stony Mountain Penitentiary. Steele and the others drew varying terms of from one to two years in the police guard-room at Macleod. I have also assisted in convicting numerous persons, including white men, Chinese, half-breeds and Indians, for supplying liquor to Indians. I recall an incident in which I acted a unique lawful part. It was in 1908 and I was a scout at Cardston. Complaints had reached Inspr. W. H. Irwin, O.C. the sub-district, that white men were giving liquor to the Indians. The residents of Cardston, which was and still is a Mormon settlement, were very much opposed to liquor. The inspector called me to his office and told me to find out from whom the Indians were getting the liquor. He gave me a free hand and asked only for results. I had no luck until one night as I was going home from visiting Crop Eared Wolf, head chief who lived in the north-eastern part of the reserve, I decided to call on Ghost Chest an Indian who was camped fairly close to town while busy with haying. Upon nearing his tent, I heard a voice say in English, “Hurry up with that girl, Joe.” I asked some of the Indians present who the speaker was, and they replied No-Pi-Ko-Wan (white man). Suspecting that he might be the person supplying the Indians with liquor, I planned to trap him. Evidently he wanted a girl to make love to. Mrs. Ghost Chest was in a nearby tent, and I asked her for an extra dress and shawl. “Why?” she queried, then laughed. She gave me the dress and after putting it on I covered my head with the shawl. When I was ready Mrs. Ghost Chest called to Joe Aberdeen, who lived with the Ghost Chests and was inside the tent with the suspect, that a girl would be over right away. I strolled to the tent and entered. The white man made a few passes at me and wanted to kiss me. I indicated that he would have to give me a drink before I would have anything to do with him, all the while shaking my head to his advances. He tried to get me to take a drink but I shook my head and signalled for him to give me the bottle. He refused to hand it over but made further advances so I got up to leave. He followed me out of the tent and became really affectionate. I nearly gave the show away by laughing in his face, but luckily it was very dark and he didn’t catch on. At length he handed over the bottle, and taking to my heels I ran in a circle and returned to the tent with him after me and the evidence safely in my hands. I tore off the dress, donned my peajacket and leaped on my horse just as he came tearing up. He stopped short when he realized I was a scout. Having already recognized him as a clerk from a store in town, I asked him what he was doing in the camp after midnight and why he was creating such a fuss. He said he was trying to buy a pony from Joe Aberdeen. I told him he would be arrested for trespassing and liquor trading and he tried to bribe me. I refused the bribe, of course, and said that he would be questioned in the morning. I turned the evidence over to the inspector, who detailed S/Sgt. Jock Naylor in charge of the detachment to make the arrest. Brought before Inspector Irwin, the suspect confessed that he had been getting the liquor from Johnny Wolf’s hotel and trading it to the Indians. He was fined $50. Staff Sergeant Naylor, Constable Clambett and I raided the hotel that night and confiscated a wagon-load of liquor. As a consequence, the hotel proprietor was heavily fined, and no more liquor was obtained from that source. A similar case occurred years later on the Blackfoot Reserve. A chief complained that the Indians on the west end of the reserve were getting wood alcohol from a white man at Carseland, Alta. More than that he did not know, and I was instructed to do some “digging.” Finally I got information from a reliable Indian which I passed to my superior and the local Indian Agent. Sgt. S. R. Waugh and Constable Davis of Calgary conducted a search on the reserve and effected an arrest. Sergeant Waugh instructed me to accompany the informant to Carseland, and not far from our destination I told the informant to go ahead. Following him I saw him enter a blacksmith shop which was suspected of being the centre of operations. I kept watch through the door and upon seeing him get a bottle of wood alcohol signalled to the police who closed in and searched both of us. They found the bottle in the informant’s pocket and the sergeant demanded to know where it came from. Of course the informant told him. During the ensuing search, the investigators uncovered in a room above the shop a 40-ounce bottle of wood alcohol and a quantity of Indian Department blankets, harness, saddles, and other articles that the Indians had “pawned.” Meanwhile in an outer shed I found four more gallons of wood alcohol. The local Indian agent fined the blacksmith $300 and costs. Some weeks later, while across the river checking the Indian camps, I came upon an Indian and his wife in a rig. It was midnight and they were drunk and fighting. I seized a 40-ounce bottle of wood alcohol from the husband and learned that it, too, had come from the blacksmith at Carseland. As a result the blacksmith was again convicted; in addition to being fined $200 and costs he went to jail. While serving his sentence, his shop burned down, and on his release he left that part of the country never to return. No Indian in Carseland has since been known to obtain liquor.  Supt. D.L. McGibbon, R.C.M.P., with Chief Duckchief of the Blackfoot tribe in ceremonial garb. I did all the interpreting for the cases at the barracks, and even for some of those that were heard in the Supreme Court. Among my duties was that of guarding prisoners during the day time, which I did not like at all. I was also stable orderly, sometimes for two months at a stretch, a duty I liked even less. Well do I remember the many times the night guard came to my quarters, woke me, and told me to saddle up for some mission to an outlying detachment. Rain or shine, summer or winter, calm or blizzard, this went on. Occasionally the trips were really hazardous. One February night I rode 22 miles through a terrible blizzard from Macleod to Standoff to deliver a summons. The storm was bad enough when I started but by the time I reached Standoff Springs, about 13 miles out, it had become a raging fury and the severe cold went right through me. Though my horse was a good one, I lost my way. Thoughts of freezing to death, a not-infrequent occurrence on the plains in those early days, ran through my mind. I let the horse have his head and eventually we came to an old dipping vat and some corrals a few miles from Standoff Springs. Stiff from the cold, I dismounted and put the horse in a shed that was there. The place had a boiler room, so I found some old boards and rubbish and soon had a good fire going in the boiler. Outside the blizzard was still howling, but I was warm and comfortable. I had a nap and when I woke the storm had subsided a little. Presently I continued my journey and reached Standoff at about 4 o’clock in the morning. As I look back on the old N.W.M.P. and R.N.W.M.P. days and the handicaps and hardships they involved I am sure that they were adventurous days. By team and saddle horse over unsurveyed and roadless country a trip sometimes took hours, sometimes days, sometimes weeks. Especially trying were the periodic tours made by officers of the Force to inspect the detachments which were from 20 to 60 miles apart. Travelling conditions were poor, and tiring to these officers. I know, for I often accompanied them. Today things are different. The R.C.M.P. use motor cars – so much faster and more comfortable with heaters for winter weather and protection from the soaking rain in summer. The only real hazards now are snow-drifts and mud holes. Most of my working days have been with the Mounted Police and I am proud that my efforts, though not spectacular, have helped maintain law and order on the Indian reserves where I was employed. The name of the Mounted Police is highly respected by the Indian – and so it should be, for the Force has treated all my brothers with understanding and justice. |