Pre-Contact, Aboriginal and First Nations

Massacre in the

Hills

By John Peter Turner

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Quarterly January 1941, p. 302 - 309

By John Peter Turner

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Quarterly January 1941, p. 302 - 309

“Countless deeds of perfidious robbery, of ruthless

murder done by white savages out in these Western wilds never find the

light of day . . . My God, what a terrible tale could I not tell of

these dark deeds done by the white savage against the far nobler red

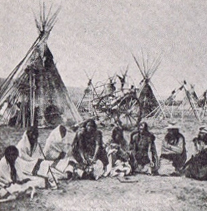

man!” Food – Festivity – Firewater – Fighting! Within the scope of these four words may be found the more noticeable indulgences of life along the Western frontier three-quarters of a century ago; indeed, all four might avail to signify common usages, past and present, among practically every race of human kind. In varying degrees, man’s tendencies are much the same the world over. Without bodily nourishment life ceases; without diversion, festive or otherwise, it dwindles; “firewater” by any other name has ever been a favourite medium of unpredictable possibilities; and the tendency to shed another’s blood (witness the world today) has thus far proven to be quite impossible of eradication. Of these pronounced indispensables, so inseparable from early western days, one – the imbibing of intoxicants – has been forbidden absolutely to the Indian; and save to uphold the honour of the nation, the fourth has long since been regarded as an offence at large. But, within the memory of a few still, time was, in one portion of Canada at least, when these four “ways of the flesh”, inflated as they often were to excesses, swayed, as nothing else could, the vagaries of human subsistence and endeavour. In the early ‘70’s, a barbaric battleground and buffalo pasture occupied the country now embraced by southern Alberta and Saskatchewan and the more northerly parts of Montana. This was the last major portion of the continent remaining to the lndian: a land in which the western intrusion had as yet made small impression, save to introduce, conjointly with the barest benefits, the undermining corrosions of civilization. For the most part, a veritable ocean of perennial grass, veiled from the world by utter solitude, flanked by the Missouri watershed along the south, by the Saskatchewan on the north, by the slowly advancing settlements of Manitoba and Dakota to the east, and by the Rockies on the west, spread immeasurably to the horizons. Along the 49th parallel an international boundary, on the verge of being surveyed, divided the dual sovereignty of this distant land. Rivers, large and small, coursed through its breadth. At its very heart on the Canadian side of the line, the Cypress Hills, accessible by horseflesh from every compass point, rose in broken and irregular configurations above the plain: a weird arena of utter savagery, a neutral tract, tenanted by resident wild creatures – buffalo, elk, moose, deer, grizzly bears, antelope, and other game – and visited by transient stone-age men – Blackfoot, Crees, Assiniboines, Saulteaux and Sioux. Far aloof, at widely separated points, trading establishments flourished, drawing from the wild plains’ hunters an enormous yield in skins and fur. Fort Benton at the head of navigation on the upper Missouri, reeking with tawdry saloons, bawdies, gambling hells and unkempt trading counters commanded an activity that extended northward into Canada. Edmonton on the North Saskatchewan, a staid, well-ordered, almost baronial emporium of the fur trade, stood behind stout palisades at a discretionary distance from the warlike Blackfoot Confederacy towards the south; and Fort Qu’Appelle, to the east, on the margin of the Great Plain, had had its inception as near the vast pastures as safety would permit. Upon these strategic forts encroaching civilization relied in order to tap the resources of the last great Indian wealth; and hither, as well as to a few subsidiary posts, both north and south, red-skinned riders had learned to come spasmodically to barter the products of the hunt and avail themselves of proffered benefits and evils. At this period, the Montana frontier, the very opposite of the orderly Saskatchewan field of trade, blazed with illicit licence. South of the line, a flagrant disregard for civilized amenities was rampant. The law of the trigger prevailed. White men and red continually vied for mastery. Crime of every description waxed bold and dominant. To be expert on the draw was to boast an enviable superiority. Gold dust was useful, but horses were wealth, power, prestige, and the only quick transport on the plains; and horse-stealing – a deeply-rooted Indian virtue -- probably the most unforgivable malfeasance of the West, had become by adoption a popular expedient among a host of hardened freebooters. In glaring contrast to the ethics followed by the Hudson’s Bay Company in the North, trading methods in proximity to the Missouri consisted largely of ghastly inhumanities. For the most part, the decalogue was scoffed at. Calloused persecution of the tribes grew to be a custom – the only good aborigine a dead one. Once stripped of his possessions, the Indian was vermin. Frontier heroes, exponents and expungers of the law, side-armed sheriffs, murderers and degenerates – all the good, bad and indifferent strata of civilized life – constituted a blunt and bloody spearhead that had sunk deeply into the vitals of the West. Benton had grown to be a rough-and-tumble slattern of a place – the congenial rendezvous of reckless adventurers from eastern and southern communities and the haven of gold-seeking backwashes from the western mountains.  “Men, women and children were happy” Buffalo products furnished the all-important quest; but the big wolves that dogged the shaggy herds provided profitable pelts, as well as ready employment to hard-living profligates and men of shady record. Young squaws were not immune from current prices; the small, wiry horses of the Indian, procurable by fair means or foul, held variable values. Simple commodities were traded to the red men; but liquor held the stage. A tin cup of poisonous firewater would fetch a buffalo roble, sometimes a piebald pony, or a girl with raven braids. Recognizing no international boundary, the more obdurate Benton traders had instituted a reign of murder and debauchery throughout the Canadian portion of the Blackfoot realm. The establishment, in 1868, of Fort Hamilton (later to bear the more appropriate appellation of Fort Whoop-Up) and the subsequent erection of smaller posts such as Stand-Off, Kipp, Conrad, Slide-Out and High River presaged a state of lawlessness that promised evil to the Canadian scene. By the autumn of 1872, the trade in firewater had spread towards the east with the building of several log trading huts on Battle Creek in the Cypress Hills, chief of which were those of two “squaw-men” Abel Farwell and Moses Solomon. In sheer defiance of the laws of Canada and the United States, brigandage now straddled and controlled the boundary line. Utter ruination of Canada’s Indians of the plains was under way. And so to our story, gleaned from participants, eye-witnesses, and conflicting records. The year of 1872 was drawing to its close. The leaves had fallen in the wooded bluffs along the prairie streams. With colder weather threatening, a band of hunting Assiniboines, under Chief Hunkajuka, or “Little Chief,” pondered the selection of a winter camp-site. Far to the north, on the heels of the buffalo masses, the nomadic wayfarers had gathered a goodly supply of pemmican and dried meat. Men, women and children were happy; for in food, above all things, lay the magic gift of life. Not far removed, on the banks of the South Saskatchewan, a camp of Crees – friends and allies of the Assiniboines - were already settled, and thither Hunkajuka decided to repair. There would be festivity aplenty; inter-tribal gatherings of “friendlies” had ever been conducive to sociability. Besides the interests of both camps would be well served, and the long months of cold would pass amid many pleasantries. During the early winter, there was little to be desired. The dusky tenants of the tapering lodges revelled in sheer contentment. Security and plenty prevailed; festivities, whether rituals or carnivals of food, so dear to pagan hearts, followed one upon another. An occasional buffalo hunt replenished the fresh meat supply and tended to conserve the fast-dwindling pemmican and “jerky.” But soon the latter commodities were all but gone; inherent prodigality had joined with an all-too-free abandon. Worse still, for reasons unknown to the wisest soothsayers, the buffalo herds drew off to other parts. The nightmare of famine, of want beset by winter, loomed as an imminent danger. Desperation fell upon the camp, and quick decisions followed. Little Chief bethought him of the Cypress Hills, hundreds of miles southward, across the whitened plains. It was better to risk the rigours of such a journey than to stay and starve. So, with gloomy forebodings, the Assiniboines bade their compatriots farewell and turned to a bitter task. Week followed week as the hunger-scourged travellers trudged on. One by one, the aged and decrepit dropped out to die. Ponies and dogs were eaten; and, as these dwindled, the tribulations of the squaws increased. Buffalo skins, par-fleche containers, leather – all articles that offered barest sustenance-were turned to account as food. Wherever old camp-sites were found, discarded bones were dug from the snow, to be crushed and boiled. Hunters ranged desperately to no avail; while, ever closer and closer, the grim spectre of famine trailed the struggling waifs. The cold bit to the marrow. A youthful couple, seeing their only child succumb, decided it was the end; but, so weakened was the crazed young warrior following a self-inflicted knife-thrust in his vitals, he lacked the strength to complete the pact. So his helpmate survived. The threat of death confronted all! But at last the Cypress Hills was reached; and, camping in a sheltered vale close to Farwell’s post, the exhausted band, having lost some 30 lives, slowly recovered from its recent ordeal. Buffalo were numerous; smaller game abounded about the coulees and brush-clad slopes. Though helpless to travel farther without more ponies, the Assiniboine remnant, released from its bondage of cold and hunger, resumed the normal activity of tribal life. Spring was at hand; buds were now swelling on the aspen trees. Meanwhile, a related episode was being enacted far beyond the boundary. South of Farwell’s post, a matter of a hundred miles or more, in Montana, there lies another hilly outcropping – the Bear’s Paw Mountains. Working out from here, a small gang of “wolfers” from Benton had spent the winter trapping and poisoning the tick-coated harpies of the buffalo herds, and doing some trading. April of the historic year of 1873 had come, and the members of the party – all seasoned and unscrupulous frontiersmen – had packed up and were on the move. Mostly, they were men who lived hard, shot hard, and when opportunity offered, drank hard of “Montana Redeye” and “Tarantula Juice”, the principal medium of border trade and barter. With horses loaded, they struck for Benton to “cash in” and indulge in such attractions as they craved. At the Teton River, ten miles from their destination, a last camp was made, and here, while all slept, a band of Canadian Crees, accompanied by some Metis, ran off some 20 of their horses. Arrived at Benton, the maddened dupes, doubtlessly abetted by much liquor, planned a swift revenge. A punitive expedition of about a dozen desperadoes, including the wolfers, well mounted and under the leadership of an erstwhile Montana sheriff, Tom Hardwick, of unsavoury reputation, was forthwith pledged to the recovery or replacement of the stolen stock and to the fullest possible accounting in red-skin blood. At the Teton, the trail of the Cree raiders was picked up and followed, only to be lost some miles to the northward. Nevertheless, resolved to loose their venom upon Indian flesh, the potential murderers pushed on. While Hardwick and his co-searchers were casting northward, all was not peaceful in and about the diminutive trading posts in the Cypress Hills; nor in the Indian camps nearby. From time immemorial the place had been a general battleground of warring tribes, and more recently the scene of bitter hatreds engendered by the whiskey trade. Horse-stealing and spontaneous killings were confined to neither side. Testimony criss-crosses and is entangled in every attempt to lift the veil from the utter depravity attendant upon the first trading incursions from Benton to this historic spot; records left by one side contradict the other; details are muddled in keeping with the drunken brawls and liquor-crazed homicides staged by whites and Indians. But from sworn statements of whites and the obviously faithful chronicles and memories of several Assiniboines involved – who still live – an account, to all intents and purposes varying slightly from the truth, emerges. Besides Little Chief’s followers who, devoid of food, had run the long gauntlet of the winter plains, several bands of the same tribe were encamped in and about the hills, - principally one under Chief Minashinayen, who had wintered in one of the many sheltered coulees, and lost a number of ponies to enemy raiders. None of these Indians had been south of the boundary during the winter. With each and every camp the whiskey traders had been driving a brisk and unscrupulous trade for buffalo robes and furs, but, with the first days of spring, the camps began to move to summer haunts. In addition, 13 lodges of wood Mountain Assiniboines had drifted in from the east and joined Little Chief’s camp on Battle Creek, doubtless attracted by the presence of the traders. And some 40 or 50 lodges stood clustered below the shelter of a steep cut-bank, on the east side of the creek, directly across from Farwell’s post. Ten days previous to the arrival of Little Chief’s band from its painful trek, a story became current that three horses had been stolen from Farwell’s by passing Assiniboines. Perhaps they had strayed, as the corral gate had been left open. In any case, whiskey was flowing freely, and George Hammond, the owner of two of the horses, seemingly an advance member of the Benton gang, had worked himself into a frenzy and sworn vengeance upon all Indians in the neighbourhood. But Little Chief’s Indians, who had consumed or worn out all but five of their own mounts, had picked up one of Hammond’s missing horses on the way in and returned it to its owner. That same night, in the budding month of May, Tom Hardwick, with part of his gang, rode into Farwell’s. Within the log trading post the lid was off! Next morning, the rest of Hardwick’s men arrived. Drinking grew boastful. Farwell kept his head, but Moses Solomon joined in the festivities. Meantime, two kegs of liquor found their way, gratuitously, to the Assiniboine camp. Someone at the post, in his cups, turned the horses out from the corral, and, soon afterwards, Hammond announced in whiskey-sodden expletives that his horse, returned to him only the day before, had again been stolen - by the very Assiniboine who had brought it in. Farwell argued otherwise, and offered to have two horses from the Indian camp delivered to the complaining Hammond backing his word by striking out, across the creek, for that purpose. Little Chief readily complied with the request, offering two horses as security. Meanwhile he sent out some young Indians to search for the missing animal, which was found quietly grazing on a nearby slope. It was now past midday. While Farwell talked to the chief, several of the Benton gang called to the trader to get out of the way. Well fortified in liquor, they were obviously out to kill! Startled, Farwell shouted back that, if they fired, he would fight with the Indians. He urged the gun-men to hold off until he went to the post for his interpreter, Alexis Le Bombard, in order that both sides might talk the matter over. This was agreed to; but barely had he left when shots rang out.  Assiniboine Camp,

Cypress Hills

Assiniboine Lodges, Cypress Hills What followed has been the subject of many versions. From intoxicated minds stories would naturally disagree; falsehoods would spring from the guilty; exaggerations from onlookers. The truth would have it that many of the Assiniboines were hopelessly drunk. Thanks to the liquor purposely bestowed upon them, few of the Indians could offer resistance. The chief of the Wood Mountain band, which had recently been added to the camp, lay helpless. Little Chief was in his senses, and the few who were sober, notably the squaws, having sensed imminent trouble, strove frantically to bring the helpless warriors to their wits. The first shots fired may have been from one or more of these – though it would seem that ammunition was woefully meagre in the camp. The 12 men under Hardwick were joined by others including Hammond, their apparent leader, as well as by Moses Solomon, the trader. Two had been left behind to guard the buildings. No matter the nature of the preliminaries, bloodshed to a certainty was close at hand. Murder, cold-blooded, besotted, and, under the circumstances, particularly merciless and ghastly, was inescapable. Little Chief’s people assuredly had had no part in the horse theft on the Teton. They had committed no greater evil than to drink the white man’s poison. But, in the minds of the Benton gang, it was sufficient for the purpose that they were Indians. That May-day afternoon was to witness stark tragedy on Battle Creek. Life in the Cypress Hills was functioning true to form; but utter savagery had of a sudden been confronted by a wave of civilization more savage still. Blood-lust, rendered wild-eyed and determined by copious drinking, must needs vent itself – and the Assiniboines had offered the coveted opportunity. On no account would Benton gossip have grounds for ridicule. The robbery on the Teton, even if amends in kind were not achieved, would be well and truly brought to frontier satisfaction by unerring triggers. Indians must pay. Murderous premeditation on the part of Hardwick and Hammond and their satellites has been proven. Had not the gangsters seized a position along a cut-bank commanding the Assiniboine lodges after first speculating upon the lay of the land, the affair that followed might be said to have occurred on the spur of the moment. A galling fire was poured upon men, women and children indiscriminately. Pandemonium reigned among the lodges. To the credit of Little Chief and the few men he could muster for defence, several futile attempts were made to dislodge the murderers by courageously charging the cut-break. But each sortie was repulsed by the unerring storm of bullets hurled upon it.  Massacre ground today. The Indians were camped under the cut-bank in the background. The bushes in the foreground mark the reputed site of Farwell’s post. Their position helpless, with dead and wounded piling up, the Assiniboines raced towards the Whitemud Coulee directly to the east and on the gangster’s left. Here they attempted to make a stand, but Tom Hardwick and one John Evans mounted their horses and outflanked them. They were submitted to deadly fire from the higher ground, and driven to the cover of the brush. Little Chief tried to outflank the flankers, but several men were sent round-about to Hardwick’s support. One of these, Ed. Grace, attempted a short cut and was shot through the heart by an Indian, who bit the dust a moment later. And so the killing proceeded. Hardwick and his supporters drew in from their outpost, killing Indians by picked shots wherever they appeared. The Assiniboines were murdered, routed and scattered to the winds. As the sun sank, the camp was charged, but none save three wounded men, who were promptly dispatched and several terror-stricken squaws, remained. According to the story handed down, the unfortunate women were taken to Farwell’s and Solomon’s posts, there to face a night of drunken bestiality and outrage. Next morning, the Assiniboine lodges were rifled of such valuables as they contained, and were then piled with all the Indian equipment and set on fire. Two horses were found and – probably claimed by Hammond. Dead bodies lay everywhere, but the number was never to be known. Many victims, grievously wounded, had been dragged away by the survivors. A ghastly reminder of the outrage was Little Chief’s head on a lodge pole high above the smouldering camp. The one dead white, Ed. Grace, was buried beneath the floor of Farwell’s post, which was then burned down. With that, the Benton colony in Cypress Hills loaded its wagons, vaulted to the saddle and hit the trail to Benton. Food (or lack of it), festivity, firewater and fighting had contributed to bring about a bloody climax which Canada could not and would not countenance. Then the North West Mounted Police! The famous march across the plains; the erection of Forts Macleod and Calgary in the Blackfoot realm, and Fort Walsh on Battle Creek – the coming of law and order and square-dealing. |