Pre-Contact, Aboriginal and First Nations

Roots Run Deep By Jay Whetter

Winnipeg Free Press October 8, 2022

Long before European settlers arrived, Indigenous peoples had established complex agricultural practices that are still relevant today

https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/business/agriculture/2022/10/08/roots-run-deep-2

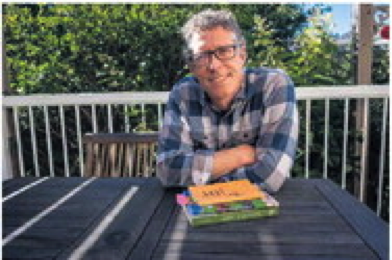

The view of the Chain Lakes from the hill on Jay Whetter’s family farm in southwest Manitoba. The land was traditionally farmed by the Sioux for generations. MY favourite place on Earth is a hill on the farm where I grew up in southwestern Manitoba. Furry, lilac-coloured crocuses, yellow cowslips, wolf willow and other plants I cannot name grow among the grasses along the gentle incline to this high point of native prairie. Rocks covered in orange, white and sage-coloured lichens dot the way. From the top, I can see our farmhouse and old red barn to the east. Three little lakes, Chain Lakes, fill the valley below. My parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents all climbed that hill. And before them, the Sioux. While I always knew the land had an Indigenous history, I didn’t know until recently that the Sioux have farmed the land for generations. I’m an agriculture journalist. Though I now live in Kenora, for a quarter-century I have written about grain farming on the Prairies: how to improve profits for canola, wheat and peas; how to use fertilizer more efficiently; how to control pests while protecting biodiversity. I write about a better farming future but hadn’t thought much about the past, or how the past might shape our future, until a man I met during an agriculture conference coffee break recommended a book. I don’t remember the conference or the man’s name, only that he worked with First Nations. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission had released its report, and the words of its chief commissioner, Murray Sinclair, were fresh in my mind: “We have described for you a mountain. We have shown you the path to the top. We call upon you to do the climbing.” I bought the man’s recommended book — Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation and the Loss of Aboriginal Life. In it, author James Daschuk describes how killing the bison herds led to the devastation of the Indigenous population. Yet, Daschuk wrote, the Dakota Sioux survived the systematic destruction of the bison herd better than other nations. The reason: they were farmers. Curious to learn more, I contacted Brandon University and found Mary Malainey, a professor in the department of anthropology. Malainey had evidence that the history of farming in southwest Manitoba dates back to the late 1400s. She invited me to an archeological dig in a sheltered bend of the narrow muddy-watered Gainsborough Creek not far from where I grew up. Along the creek, an amateur explorer had discovered two hoes made from bison shoulder blades and alerted Malainey. About a dozen archeologists and aides bedecked in Tilley hats and khakis, off-gassing the whiff of bug spray, were on-site when I visited in 2019. They worked in the creekside bushes, sifting through soil painstakingly extracted from one-metre-square dig pits. They discovered remains of a tool-making workshop and residential debris — evidence, along with the bison-bone hoes, that Indigenous peoples had lived and farmed the area centuries before European contact. Archeologists don’t yet know who these 1400s farmers were, but when I asked Sara Halwas, an archaeologist at the dig site, how I could learn more about early Indigenous farmers, she recommended Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden. Written in 1917 by anthropologist Gilbert L. Wilson, the book recounts the crop production practices of Hidatsa woman Maxidiwiac, also known as Buffalo Bird Woman. She was in her late 70s when Wilson interviewed her, capturing minute details of her farm at Like-A-Fishhook village on the Missouri River in North Dakota, 200 kilometres south of the Gainsborough Creek site. Maxidiwiac knew every detail about crop production, harvest and storage. She even knew about pollen drift and selective breeding. Maxidiwiac was not just a farmer, she was an expert farmer. “Corn planted in hills too close together would have small ears and fewer of them,” she told Wilson. Farmers plant corn in wide rows to this day. She also filled the space between corn plants with beans that fix their own nitrogen — an essential nutrient for plant growth — from the air, and with squash that provided ground cover to limit weed growth. Weeds use up moisture and nutrients from the soil, reducing crop yield. Reading Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden was like a lightbulb turning on. This old woman was rewriting my family history. I filled my book with underlines, asterisks and annotations. Maxidiwiac made me realize that present-day tools of convenience, like synthetic fertilizers and pest control sprays, have reduced our need for time-honoured techniques proven over centuries to work. We may want to look at how these methods could help us today. Farmers around the world, including Canada, are pressured to be more efficient with their use of nitrogen fertilizer. Plants need nitrogen — and fertilizer is essential to maintain yields per acre — but extracting nitrogen from the air to make fertilizer takes a lot of energy, and nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, escapes from fields where these fertilizers are applied. To improve nitrogen use efficiency and reduce nitrous oxide emissions, Canadian farmers are using techniques to apply fertilizer when the crop needs it, to place the product deep enough in the soil to prevent losses and at rates that match the yield potential of each piece of land. This is a Maxidiwiac-esque efficiency of resources. In the spirit of Maxidiwiac, some farms, though not many at this time, are intercropping: planting in the same field a mix of legumes like peas that can fix their own nitrogen with plants like canola that need a lot of nitrogen. Today’s farmers are also wrestling with a rise in herbicide-resistant weeds. Fighting the problem will require a multi-pronged approach that doesn’t rely entirely on herbicides. One prong is to have crops achieve full ground cover as quickly as possible, using the crop itself to suppress weed growth. I’m not saying farmers should grow squash between rows of wheat and canola, but Maxidiwiac reminded me that ground cover is an old and proven technique. In an article I wrote recently on integrated weed management to reduce the reliance on herbicides, point No. 1 is to make the crop more competitive — increase the density of plants to reduce the space left for weeds. That is what Maxidiwiac did. Reading about the expertise of this farmer made me wonder about Indigenous farmers of today. MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS  The author is rethinking his family’s farming history since learning of Sioux agricultural practices.  Agriculture journalist Jay Whetter TOM THOMSON / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS |