|

Varieties of Industry

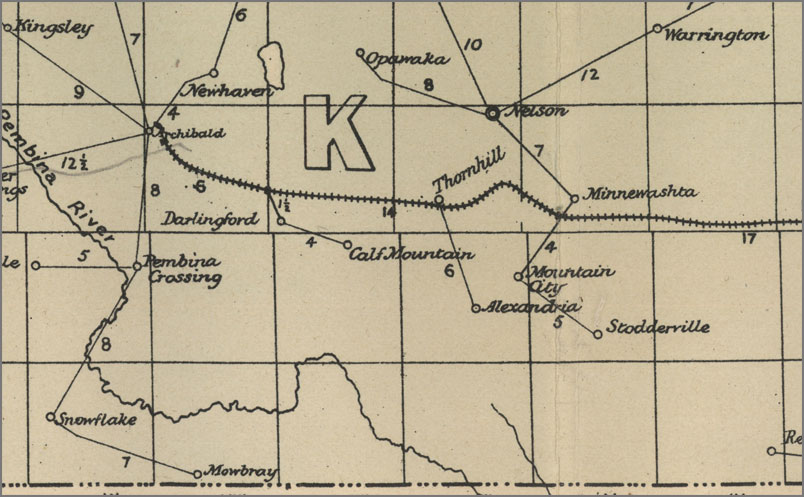

| Introduction First… a word from wikipedia… A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separated from its chaff in preparation for grinding. We will use the terms gristmill, grist mill and flour mill interchangeably because all three are used in the source material. ……… A Trip to Gregory’s Mill Cartwright pioneer, A.E. Steel, writing in the Cartwright local history, Memories Along the Badger Revisited, tells us this story of a trip he took in the early 1880’s. The mill in question was some distance away, outside of the Boundary Trail region, but we include as an illustration of the forces that prompted the establishment of local mills, and as a slice of life from the times. Our first grist of wheat was taken to the flour mill at Glenora and a farmer got his own wheat ground into flour and got all the flour, bran and shorts that he owned. After that we went to Wakopa flour mill owned by Harrision Bros., and again I have made a number of trips to the Souris mill. The mill was equipped with the Hungarian Patent process and made an excellent grade of flour. Each round trip took four long days to go and return with oxen. The mill was kept running day and night, and if we were fortunate our gristing was done right away and we would be able to start for home without losing any time. The mill was owned by a man by the name of Gregory, and anyone that had to stay overnight was accommodated at his house. He had plenty of stable room and feed for the teams and the charge for man and beast was very reasonable. I remember Bob Blackwell and myself going with our grists to the Souris mill with the oxen and wagon after the freeze-up. The weather was lovely so we travelled until quite late the first day and then camped out for the night. We had plenty of with which to keep us warm. The next morning we hitched up early and got to Dunlop's for breakfast. (The town, Dunrea, is situated on that place now, or at least part of it). The townsite is on part of two farms that were owned by Dunlop and Ray so the town was named after the two farmers. Leaving Dunlop's, we entered Lang's Valley and travelled it for a few miles, then crossed up the other side and the next valley we entered was the Souris and then on across the river to the mill. This time there were a lot of grists ahead of us and that meant staying at the mill two nights instead of one. We could get our meals at the house but there wasn't sleeping accommodation for all, so a number of us slept at the mill above the engine room which was nice and warm. We got loaded up and started for home before daylight on Saturday morning and travelled a good distance be- fore we stopped to feed our teams. After giving them a good feed we got going again. Bob said he intended to stay that night at a friend's and he would not resume the journey until Monday morning, but I decided to go on home after feeding and resting the oxen. I passed through the north end of Killarney late at night, and after a while began to feel sleepy so I wrapped a quilt about me and lay between the bags. I knew the oxen would keep to the trail so I dropped off to sleep. I don't know how long I slept, but when I awoke, I found the oxen both laying down. I got them going again and finally reached home before daylight on Sunday morning. *Cartwright & District History Committee, Memories Along the Badger Revisited, 1985 p4 Mills Were a Priority The European settlement of Southwestern Manitoba followed a process that had already been established elsewhere, across North America. People were here before services, before roads, before stores and towns They really were starting from scratch. Slow transportation and long distances made self-sufficiency a must. They came to farm, and they already knew that wheat and other grains were to be the primary crops. The prairies were opened to agricultural settlement for one main economic purpose – to grow wheat. The problem with that was that it was so far to market that there was little profit to be made. That was okay, they all knew that. Eventually rail lines would cross the land and everything would fall into place. In the meantime, subsistence was a starting point. Wheat and oats and barley were edible, even sought after, as a food supply… with a little processing. Many of the settlers from Ontario and Britain had no farming experience. Many were especially unprepared for the difficulties prairie farming would present. That wasn’t their fault – even for those with agricultural expertise, prairie farming was a whole new game. But most of the newcomers were pretty smart and self-sufficient. All of them kniew where flour came from, and that it could be used to make bread. The same with oats and oatmeal. They knew about flour or grist mills. Every community back home had one. Quite a few of them even knew how they worked. Having a gristmill nearby, where one could at least exchange wheat for flour was a crucial advantage in making a homestead sustainable until a railway would arrive. Turning wheat into flour represented Manitoba's first step in becoming an industrialized society. Flour milling was practised by the province's aboriginal peoples long before Lord Selkirk's settlers engaged in the activity. When Manitoba gained provincial status in 1870, most flour mills were concentrated in the vicinity of the rapidly emerging city of Winnipeg. Flour mills supplied flour for the practical consumer needs of the district residents. The First Mills – Pre-Railroad Settlements In a sense the early mills were services that hoped to become towns. With the coming of the railway links we saw the creation of more lasting towns. These towns wanted a gristmill and would often offer what was called a Mill Bonus to attract such a business.  This map shows postal routes and pre-railroad communities as of about 1884. The period from 1881 and 1882, known as the “Manitoba Boom”, saw intense speculation in land sale – especially in town lots. Everyone knew that the population of rural western Manitoba was going to explode. Towns would be built, businesses established, and money would be made. The problem was that nobody was sure where all these new towns would be located. It all depended on where the railway lines would run, and where the railway company would decide to put a station. Although some railway surveys had been undertaken and some lines had been planned, no one knew where the stations would be. So some enterprising landowners decided that a piece of land they owned might just be a good spot for a town Speculating in town lots was a bit like participating in a gold rush. You stake a claim and hope it pays. Exaggerations and outright lies were the tools of that trade. To sell the lots the promoter had to assure prospective buyers that the rail line was a sure thing. Another selling point was having a mill. Conclusions The establishment of the rural milling industry was a direct result of the confidence demonstrated by those entrepreneurs and farmers who invested their fortunes, toil, and tears in the development of the province’s agricultural resources. The conversion of wheat into flour for practical consumer purposes provided evidence to investors that the region was worthy of future development. The agricultural sector provided the engine for the growth of the entire province. Four milling played an important role in this achievement. Even though many settlers had milling experience, and there was a definite need for the service, they weren’t prepared for the seasonal nature of prairie rivers and soon learned that water power wasn’t reliably available. Thus it was more costly here than in the east, and making a profit was more difficult. The decline and extinction of small independent flour mills across Manitoba can be largely attributed to the uncompetitive position in which these mills were placed by the large milling companies after the first World War. Consumers of flour gravitated toward the more inexpensive product produced by the large mills. Lack of business suffocated the independent millers and most were driven out of the business. The large milling concerns could not only undercut the price of flour that independent millers offered, but they operated at a distinct advantage because of their large reserves of capital. The large mills also had greater funds at their disposal for advertising. Over the course of the twentieth century, Manitoba’s rural population base began to decline; rural residents migrated to urban centres. All these factors played a part. Although the flour milling industry in rural Manitoba faced its perhaps inevitable decline, the role it played in that short period of transition to an agriculture based economy was both important and interesting. Sawmills After treking half way across a continent in crowded lake boats, slow river boats, poorly appointed trains; after finishing the journey in ox carts, open wagons, or even on foot; the thought of building your first home on the prairie must have been appealing, to say the least. If the recent stretch of your long journey took you through the thriving town of Emerson or the well-populated city of Winnipeg, both appearing to have been visited by civilization, you might have some expectations that your new home might be similar to the ones you stopped in along the journey. Welcome to the prairies. Even if you could afford a nice frame home, perhaps forgoing the picket fence, the building materials were hard to come by. This new country didn’t seem to have lumberyards. Shipping lumber from the bigger centres was expensive and time-consuming. In much of southern Manitoba, timber was scarce. The scarcity of trees meant that the open prairie was easy convert into productive cropland. The downside was it was a long way even to get firewood, let alone building materials. The Pembina - Manitou area was a bit of an exception in that, the along the Pembina Escarpments and along the Pembina River and Rock and Swan Lakes, there were well-wooded spots. That allowed early settlers in that vicinity the option of using locally sourced wood. If there was timber nearby, one of the first businesses set up in those pre-railroad settlements was a sawmill. Some of those sawmills were small and temporary, not necessarily designed for commercial use, but set up to get a few buildings up. Pioneer J.E. Parr describes the first sawmill in the Rock Lake area… “Two posts were out in the ground about twelve feet from the precipitous bank, with timbers from the top of the bank to each post, far enough apart to roll logs out on. “ The saw mill machinery consisted of a long pit-saw and two men. When a log was placed over the pit, the bark roughed off, and chalk-lined from end to end, with lines one inch apart, one man would stand up upon the log and the other in the pit , and operate the mill. Mr. Thos. Sandow’s house, built on section 18-2-11, was the first raised in the district, and the roof was sheeted with lumber from this mill” (McKitrick)  An unidentified sawmill site The era of locally milled lumber was short, but important. Most of those first sawmills were in villages that would disappear when the railway arrived and new towns were born. That rail service also allowed for an easily accessible supply of milled lumber in most areas. Brickyards Manitoba is geologically blessed with thousands of clay deposits, hundreds of which have been exploited over the past 150 years for brick manufacture. The “Golden Age” of this aspect of Manitoba’s building history was from 1880 to 1912. There were about 60 major clay sites and about 175 brick manufacturing plants that provided the billions of bricks that were required for Manitoba’s major building boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The details of industrial operations were not often covered in local newspapers and so it is only possible to provide a sense of typical operations. The work was hard and the days were long. The pay was modest, about $2 a day, but it was steady, at least for the duration of the season, usually from May (when the frost left) till August or September. Even small yards had up-to-date technologies such as steam-power. A typical operation featured the large covered drying sheds that new bricks were laid into. It was the final stage of the brick-making operation that usually distinguished a major from a minor yard: whether the brick was fired in a scove or beehive kiln. The scove kiln. Most likely used in most operations in the southwest corner, was a less sophisticated technology, but one that was still effective enough to produce good quality brick. Burnings lasted about seven to eight days, and when the outer shell of bricks on a scove kiln was removed, workers discarded the disfigured and discoloured bricks nearer the fire source. The Brick House The first settlers often built a sod hut for those first few years. Logs were hard to find on the open prairie, but those living along near the Pembina Escarpment or in the vicinity of Rock Lake might start with a log house. Settlers who arrived with a bit of cash in hand might opt to bring in building supplies, but many had to wait for that first frame dwelling. Brick was desirable as a building material, but was even more expensive to ship than milled lumber, so it was some time before brick buildings became popular. What helped that process along was the fact that some of those new settlers came with some experience making bricks, and they kept an eye out for deposits of clay that would serve that purpose. Food Processing In the same way that grist mills or flour mills were an obvious way to convert local product into food, butter and cheese factories were an early attempt to process milk locally. Several of these were small operations focusing on the local market. In the same way that grist mills or flour mills were an obvious way to convert local product into food, butter and cheese factories were an early attempt to process milk locally. Several of these were small operations focusing on the local market. Other less common enterprises include S.S. Mayers Stock Medicine Company started in Cartwright. It was so successful that he moved to operation to Winnipeg in 1910. A rather unexpected initiative was the establishement of soft drink manufacturing in Manitou, Mather, and West Lynne. Then, as now, there were obstacles to overcome in trying to operate a manufacturing enterprise in small town. The bottom line was that many of these enterprises were just getting underway when the explosion in transportation technology, the extension of rail lines, and beginning of the automobile age, changed everything. Lime Kilns Some years ago, while walking along the high riverbank, I found what appeared to be an old well lined with fieldstones. I gave it little thought until I learned about the small lime kilns that settlers often constructed to make mortar for the many stone buildings that dot the southwestern corner. They are another example of small, local, do-it yourself, prairie enterprises.  The remains of a small kiln. Early settlers used it to purify and freshen damp basements, in the henhouse, in cement and plaster and for whitewashing walls and ceilings. Part of the spring housecleaning ritual was the whitewashing of the interior of the little building with the half moon cut in the door. The only "accessory" in that little building was a nail and string to hold the previous year's Eaton's catalogue, which was used to the very last page. Angus McRuer describes one located near his Desford-area farm… “This kiln was on a rise of land sloped to the north. A hole eight feet deep by ten feet across was made at the top of the slope. A trench three feet wide by thirty feet long was dug, starting at the bottom of the hill, up into the bottom of the big hole. It was like a big clay pipe. The trench acted as a damper.” To prepare for a burn, stones were placed in the kiln leaving an arch at the bottom to hold the fire. The process took three days to reduce the limestone to powder. In addition to using it for making mortar, people used it to purify and freshen damp basements, and in cement and plaster and for whitewashing walls and ceilings. There were several of these small local enterprises in our region. Many are small and barely recognizable. They are usually on the side of a creek bed or hill to allow access to one side of the kiln to feed the fire and to provide the necessary draft to create a hot and steady burn. “This kiln was on a rise of land sloped to the north. A hole eight feet deep by ten feet across was made at the top of the slope. A trench three feet wide by thirty feet long was dug, starting at the bottom of the hill, up into the bottom of the big hole. It was like a big clay pipe. The trench acted as a damper.” To prepare for a burn, stones were placed in the kiln leaving an arch at the bottom to hold the fire. The process took three days to reduce the limestone to powder. In addition to using it for making mortar, people used it to purify and freshen damp basements, and in cement and plaster and for whitewashing walls and ceilings. There were several of these small local enterprises in our region. Many are small and barely recognizable. They are usually on the side of a creek bed or hill to allow access to one side of the kiln to feed the fire and to provide the necessary draft to create a hot and steady burn. Once it was started, the fire in the kiln was kept going day and night. Most of these operations ceased in the early 1900’s as commercial building supplies became more readily available. |