The Great Northern Line

Foreword

The Brandon,

Saskatchewan and

Hudson's Bay Railway, a subsidiary of the Great Northern Railway from

the U.S.,offered

service from Brandon to the small town of St. John's,

North Dakota where it made connections on the Great

Northern lines south to Minneapolis, east to Duluth,

and west through Montana to the coast.

The line, born as it was in the optimistic times of expansion, was

perhaps doomed from the start, but it did have its impact for a few

short decades on several communites south of Brandon, and in a limited

way, on the city itself.

Where is Bunclody?

I’m pretty

sure that the first time I ever heard of Bunclody, someone was

making fun of the name. It was Vince Dodds, the morning man on our

local

(Brandon) radio station, and he had a running bit involving checking in

on

the exploits of the Bunclody Bridge Marching Band. Something like that,

a

gentle comment about small town life at a time when small towns were

rapidly

disappearing. It's a pleasant name, Irish in origin, and, yes, perhaps

a

bit fanciful when compared to the nearby communities - with their

stolid,

sensible names like Hayfield, Carroll, or Brandon.

In

any case, the name must have impressed me enough to remember it, but

not

enough to prompt a visit for many years.

It

wasn’t until decades later while scouting canoe trips on the

Souris River

that I made my first visit. Bridges are all-important when planning

short

river excursions, that's where one finds the most user-friendly access

to

the river, and I soon became acquainted with all such points in western

Manitoba.

What

a treat it was to finally see the place. Yes, you could see why

the

radio jokester had singled it out. By the sixties many former prairie

villages

were that in name only. It was as if we were reluctant to take down the

road

signs, change the road maps and admit defeat. Bunclody turned out to be

just

a shady roadside park nestled alongside a gravel road near the river

where

it brushed against the southern rim of a wide valley. It barely

qualified

as a ghost town! At first glance only the two cairns in the park gave

evidence

of any past settlement.

It's

funny how you can miss things, and odd that in driving through the

valley

I didn't notice the way the road southward up out of the valley cut

through

a narrow ridge running along the hillside. Not so odd perhaps that on

several

trips up the gentle slope northwards from the river, I failed to notice

the

signs of a substantial embankment approaching the river a kilometre to

the

east; unmistakable evidence of a railway line. It's obvious if you know

what

you're looking for, but a quite unobtrusive element of the rolling

valley

landform if you don't. And its quite understandable that later as I

paddled

downstream from Souris to where our vehicle was waiting by the Bunclody

Bridge,

I failed to notice the same embankment curtailed on either side of the

river.

The constant erosion of a riverbank over a few decades had erased much

of

the evidence.

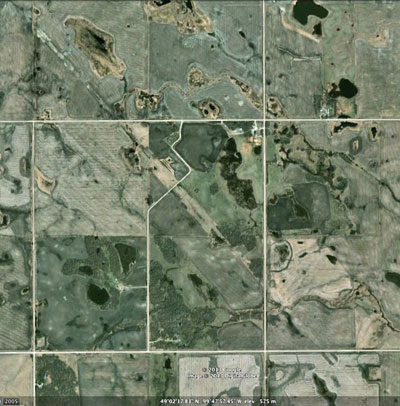

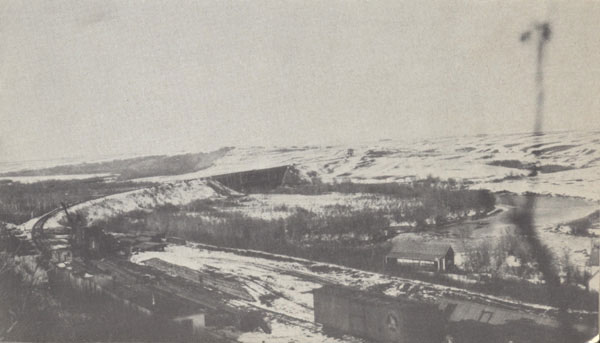

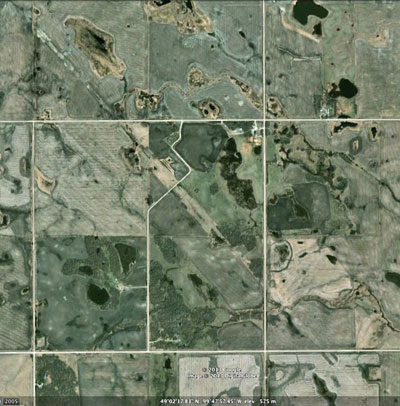

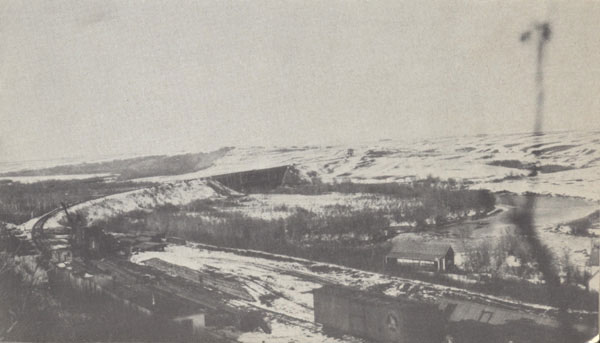

Can

you spot the rail

line

embankment, along the

Can

you spot the rail

line

embankment, along the

centre of this photo?

So what I missed

seeing in my first visits to Bunclody was the evidence of a rail line

that had once crossed the river at that point. It was another few years

before a friend from the area told me about the rail line,

and took me out to a neighbour's farm to see the huge

concrete culvert at the base of what looked like a dam across a steep

ravine. It is now almost plugged with debris, but he remembered playing

in it as a child, taking the dare to pass through its 100 metre length

to the other side. What looks like a dam is actually a bridge,

timber-framed then stabilized by earth fill that hides the framework

– a common way of crossing the deep cuts running towards the

Souris River. On another trip to the area my wife and I climbed the cut

bank along the roadside and followed the overgrown rail-line path,

first south for a few kilometres, and then north for a ways until it

abruptly ended, leaving us looking across the Souris River to where it

continued on the other side. Knowing that, it was easy to recognize the

signs in the river below, a small island that once served as a footing

the center support for the bridge.

The old line

is quite visible from the air.

The elevator and station were about half a kilometre to the right.

And that's how I

first

learned about the oddly-named Brandon, Saskatchewan and Hudson's Bay

Railway and its American parent company the famous Great Northern Railway.

We all know about the

importance of the railway in the development of the

west. Those two venerable Canadian institutions; Pierre Berton and the

CBC,

have made it hard to escape the role the building of the C.P.R. played

in

our history. Railways have been romanticized, eulogized, and demonized,

but

never ignored.

Equally

true however, is the fact that in much of rural Manitoba, and

across

the prairies, the rails are being abandoned, torn up and inevitably

forgotten.

The railway boom lasted only a few short decades before retrenchment

began.

For rural communities the presence of a rail link went from being

indispensable

to being inconsequential in a less than forty years. We had barely

completed

criss-crossing the land with lines when we began taking them up.

Sometimes

we built too many.

That

may well be the case with the much-anticipated route from Brandon

south

to the U.S. Border, seen at the time as a forward-thinking link with

the

extensive Great Northern Railway. But to rural people in southern

Manitoba

at the end of the 19th century, there couldn’t be too many rail

lines. Many

of the first settlers had waited patiently for the first lines, which

in

many cases were delayed by the infamous “monopoly clause”

in the governments

deal with the syndicate that built the CPR. Even after the

Greenway

government was able to end the 20-year monopoly in 1888, many farmers

still

had a long haul to get their grain to the nearest elevator and many

complaints

about the service they received, specifically6 the availability of an

adequate

number of rail cars in peak periods. Anything that would reduce the

length

of those trips, plus add an element of badly-needed competition was

welcome.

(Minnedosa Telegram Nov. 17, 1906

It

wasn’t just farmers who wanted this railway. There was a lot

of boosterism

associated with railway building. There was profit to be made in the

building

of the infrastructure and in the establishment of related services. The

arrival

of a rail link seemed to secure the fortunes of any small settlement

and

enhance the prospects of existing towns. This line was destined for a

short

life span, but in that short time it certainly did provide a much-need

service,

and made quite an impact along its route.

As

early as 1898 Brandon's City Council was hearing proposals and

rumours

of proposals for a north-south line that would allow a direct link with

the

Great Northern Railway in North Dakota.[1] Such a line would provide a

direct

link to Minneapolis, the economic heart of the American mid-west.

Brandon,

having established itself early as an important stop on the CPR, was

facing

the possibility of being bypassed by other east-west lines and was

determined

to maintain its position by capturing a north-south line.

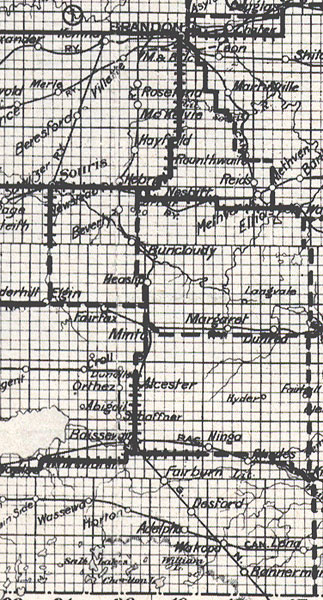

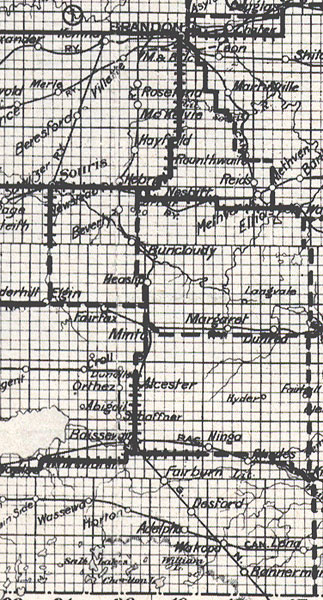

Rail

lines as of 1900

The

whole

operation

reflected the optimism of the times and the fact that

no one could predict the path development would take on the Prairies.

In

particular, no one predicted the impact that the newly-invented

automobile

would have on transportation, and that it would quickly render

passenger

service unprofitable. Perhaps the most interesting, and perhaps

slightly

ironic aspect of the unknowable future was that the productivity

allowed

by better movement of farm products allowed farmers to expand their

holdings,

in turn sowing the first seeds of the rural depopulation that would be

a

contributing factor in the demise of rail service.

But that was all in the

future. The

present required growth and expansion,

all facilitated by better transportation.

While the first plans

failed to

materialize, by 1903

the seeds of a workable

proposal were being sown and spurred on by prominent local businessmen.

Brandon's

own Clifford Sifton, Minister of the Interior, was likely a factor in

the

parliamentary approval for a charter for a line from the U.S. border to

The

Pas. That charter lapsed and had to be renewed in 1905, this time with

the

behind-the-scenes support of American J.J. (Jim) Hill of the Great

Northern

line for an operation to be known as "The Brandon, Saskatchewan and

Hudson

Bay Railway." [2] That catchy title certainly reflected the frontier

optimism

of the age of railway expansion. The first and, as it turned out, only

stage

of the project was to be a 115 kilometre track to a border crossing

south

of Boissevain where it would continue to connect with the Great

Northern's

well established U.S. network. It turns out that Hill had no intention

of

heading either to Saskatchewan or to Hudson Bay under Great Northern

ownership.

[3]

There were several issues that the

city

fathers had to confront. Of course

the C.P.R. objected, that was to be expected. Some objected on the

grounds

that it was an American intrusion into the market that would divert

trade

from Canadian routes. Others had reservations concerning the ownership

of

the Great Northern. Jim Hill had been invol

ved

in the original

development

of the C.P.R. and at one time had hoped that the eastern portion of the

new

line would pass beneath the great lakes through the U.S., facilitating

easy

links with his other holding and providing the basis for a North

American

rail empire. When the decision was made for an all-Canadian route he

withdrew

from the project. Some said his main motivation in establishing this

North

South link was to get back at the C.P.R. It is more likely that Hill

simple

wanted to expand his operations in a most logical fashion with another

Canadian

link. [4]

There was a necessary and habitual

attempt at

secrecy, mainly to forestall

land speculation that would drive up the prices of required stations

and

related property, and also because of local opposition to the American

ownership.

The local promoters tried to maintain pretense at first, to a Canadian

component

to the corporation, but it turned out to be totally a Great Northern

operation.

After witnessing the orgy of land speculation and townsite swindles

that

preceded the C.P.R. on its pathway west, the railways had learned a

lesson

and regularly went to such lengths as to develop secret telegraph

codes.

Thus a communication from R.I. Farrington to Louis Hill on August 7,

1905

read: "Duchy Jame Alfred anything dwindle about reasoning for brusher

outlive

loquacious." Translated it meant, "Do you wish anything done about rail

for

Brandon line" [5]

Most

Brandonites

were all for the new line. And those along the proposed

route could see the possibilities. For many farmers it would cut the

distance

they had to haul grain. Aside from the historical reason fro distrust

of

the CPR, there had been some widespread dissatisfaction with that

railway,

amid concern about inefficient grain handling and allegations of

collusion

with elevator companies to the detriment of producers. For all rural

people

along the proposed line it mean greatly increased options for

convenient

travel.

Once the deal was struck the line was

started

without delay, beginning

in

1905, and decisions were made quickly regarding the route and placement

of

stations. Despite the best effort of the rival lines to stall the

establishments

of the necessary crossings at Wakopa, Boissevain and Minto, the line

worked

its way northward at an astonishing pace. Rights of way were purchased.

Established

communities of the Boissevain, Minto, and, of course Brandon would be

on

the route. New sites of Bannerman, Bunclody, Hayfield and Heaslip were

surveyed,

although not all developed into villages. A deal was struck with McCabe

Elevators

for grain handling facilities and Great Northern cash was provided up

front

to build the twelve facilities. Even the sites of Fairburn, Alcester,

Griffin,

Healip, McKelvie and Roseland would have elevators but even in those

optimistic

times villages were not anticipated.

While stations were located at most of

the villages

even stops that

didn't

evolve into real villages got waiting rooms complete with pot-bellied

stoves.

Stops like Beverly (originally called Webster) and Hebron, closely

spaced

between Bunclody and Hayfield, and known as "sidings", got loading

platforms.

Several sites had dwellings for section foremen and bunkhouses for

crew.

Water towers, a vital part of the infrastructure in the days of the

steam

locomotives, were closely spaced on this line with structures at

Bannerman,

Boissevain, Minto, the Souris River Crossing near Bunclody, Hayfield

and

Brandon. Each had a pumping manager in charge. Crucial to the whole

operation

was a 30 year contract to carry the mail. Post offices were established

along

the line or in several cases moved to be closer to the line. [6]

By

1906 the trains were running, bringing an immediate benefit to local

farmers,

improved mail delivery, easier access to both Brandon and the point in

the

US, and a much improved distribution of consumer good into the rural

area.

According to Great Northern records, the

line ended

up costing

$2547281.37.

[7] That price was perhaps a little steeper than they had intended. The

CPR

competed for contractors, offering work on its own lines and thus

boosting

prices. The GN countered by offering local farmers work on the easier

grades

with contracts going out in 1906. A story in the Boissevain Record

insisted

that between three and four thousand men were employed in that year. It

was

the only common carrier railway line ever build in Manitoba with no

public

subsidy of land or money, in fact, it often paid inflated prices for

land.

[8] The extra cost was the first in a series of circumstances that

limited

the profitability of the line.

A Ride on the GN Line

Let's hop on

board as

the train departs from St. John's, North Dakota, just

a few kilometers south on the Manitoba / US border where connections

could

be made to points south (Minneapolis) and points west on the Great

Northern

Line.

In

charge is

St.

John local, Charlie Bryant, long time conductor, well-known

to folks all along the line, a man who wouldn't hesitate to make an

unscheduled

stop or other accommodation for a good customer.

The line stretches across flat

prairie,

broken here and there by a slough

ringed by low willows, a low bunch of aspens in the corner of a fenced

pasture,

and a farmyard with the beginnings of a shelterbelt. To the left

(west) in

the distance is the outline of Turtle Mountain, low and thickly

wooded

with oak and aspen. But straight ahead lies an uneventful horizon.

Before

long

we're

at the border and four

kilometers past that is the newly-founded village of Bannerman, a place

that

owes its existence solely to the railway.

Bannerman

The

site is still quite visible on Google Earth while very little evicence

remains on the ground.

Of all the newly

created and boosted villages along the line, the rise and fall

of Bannerman was the most dramatic. The new rail line. coming as it did

from

our southern neighbour, required a Port of Entry, naturally the first

stop

after a border crossing. A spot on NE 15-1-18 was suitable and

available.

Settlement in the area, just three kilometres from the US border dates

from

around 1880 when James Henderson Sr. was the first settler to file in

this

vicinity. In 1905 as line approached, the town of Bannerman sprang into

existence

with excitement and a sense of possibility, the first and only port of

entry

by rail west of Emerson in Manitoba. The Manitoba Telegram

ventured

the opinion that it would become “ a good live town” and

that “busy little

centres will be established” at all the townsite points along the

route.

[9]

There

was of course a rush to build homes, businesses and an elevator

and

Bannerman quickly developed a boomtown atmosphere. A hotel with large

dining

room and bar encouraged visitors especially during those years when the

prohibitionists

won the almost annual battle with the temperance folks. During the

prohibition

years the bar became a dance hall. Other buildings included a feed and

livery

barn with sleigh and buggy for hire, a lumber yard, pool room and

barbershop,

a store and post office, a blacksmith shop, harness and shoe repair

shop.

Soon a second grocery store and additional blacksmith shop was needed,

and

two dealerships for the fast growing farm implement business.

The station's status

as a port of entry meant that station had two

offices,

one for the railroad agent and one for the Customs and Immigration

officer.

These duties and responsibilities required other facilities and

enhanced

the status of the town. A detention house was soon added nearby for

those

who were not granted entry, and had to wait overnight for the train

back.

A quarantine barn was needed as all livestock was held overnight for

inspection.

To north of station were two section houses and a water tank.

Another added responsibility was

controlling the flow of alcohol as

different

and changing liquor laws always seemed to keep make smuggling a

worthwhile

venture. Agents patrolled the border in the area. Then as now border

security

was an important responsibility. Magistrate John Balfour, aided

by

town cop Sam Balfour kept the peace locally.

Each

year the circus of the Royal Canadian Shows came by the Great

Northern

to entertain at Brandon summer fair. Customs agents went to Devil's

Lake

to start inspection of the many passenger cars and the inspection was

completed

at Bannerman.

A

hotel with large dining room and bar appeared, but bar closed with

prohibition

and the building became to a dance hall. Other buildings included a

feed

and livery barn with sleigh and buggy for hire, lumber yard, pool room

and

barbershop, store and post office, blacksmith shop, harness and shoe

repair

shop. [10]

On to Desford and Fairburn...

Pulling

out of Bannerman, we are just nicely getting up to speed when

another

fledgling village appears on the horizon. But we pass by it to the

west.

The village of Wakopa, the first in the southwest corner of Manitoba

is,

a well-known fixture on the rival CN line that we are about to cross.

But

not for long.

Wakopa

had its beginnings as a stopping place on the Boundary

Commission

Trail, that well-rutted trail first etched by the expedition sent in

the

1870's to survey and describe the border region from eastern Manitoba

to

the Rockies. The store established there by a Mr. Lariviere who served

those

hardy early settlers who arrived before the big rush of the 1880's and

the

site continued to be a landmark and supply depot until the arrival of

the

a spur line branching off of a more northern line at Greenway a

kilometer

to the north. The town moved to the line and continued, enhanced by the

new

rail service, but limited by competition from the Great Northern line

passing

it just a kilometer or so west. Even in boom times this region could

only

support so many towns! [11]

With Wakopa bypassed

we soon pull in to in an even smaller place!

This village also sprang up overnight as it

were,

although an earlier post

office and store were in place to the west and had to be relocated. But

it

lacks Bannerman's boom-town vibe, just a station an elevators and a few

scattered

buildings.

Rail lines are a vital service to any

community. To

the owners, they are

a business like any other: they will survive if they are competitive.

On

the prairies, that means competing for grain delivery. To do so

elevators

or loading platforms have to be spaced closely enough to ensure that

farmers

will choose them over competitors. The Desford community began in the

late

1870's along the Old Commission Trail about 12 kilometres

south-southwest

of Boissevain, and was, like Wakopa, one of the first trading centres

in

the area.

In those first days of settlement, 1878 and

79,

settlers came by the Boundary

Commission trail from Emerson. By 1880 the preferred route was by way

of

the Assiniboine River to Millford, then south to Langvale and via the

Rowland

Trail to the Turtle Mountain area. The first stores in the area were at

Desford,

Wakopa and Waubeesh. The first general store and post office in "Old

Desford"

was owned by E. Nichol and Son.

Fred Johnston, and early resident of

Boissevain,

before the town even developed,

recalls the choice in 1884 between shopping at (Old) Desford and

Rowland

(16km NE). Another pioneer recalls Sunday Church service in the Jimmie

Burgess

home at "Old Desford". But as with so many of the first settlements,

the

location had to be reconsidered when the railways came. For Desford the

change

began in 1906. First the CN line was extended through Wakopa, Adelpha

and

Horton, just narrowly bypassing Desford, The that same year The Great

Northern

Railway bypassed to the east and a new town started to grow on that

line

about six kilometres away.

The store at

Adelpha, owned by Mr. Crummer,

was

moved four miles to Desford.

They used sixteen team of horses to drag it and the path was still

visible

in the 1970's. In no time a McCabe elevator was built. Next came the

section

house, a few residences, a station, and a bunkhouse . Qualified help

was

in short supply and the station master had to imported from the U.S.

Both

Anglican and United Churches followed, and other buildings included a

large

storehouse and garage, an oil station, and a blacksmith shop. The

population

exploded to near thirty and a community hall was deemed necessary. [12]

A cairn marks the location of Desford - all traces are gone.

A

few kilometres out of Desford

we come

to Fairburn.

These "sidings" as they

were called were put in place to accommodate local farmers, and were

never

intended to become villages.

It

may seem odd to the modern

urban-dweller,

that a

place like Fairburn rate

identification on a map, being no more than a lone elevator on the open

prairie.

One has to understand that in the early years of the settlement era

(1878

to 1885) few towns as we know them existed. When settlers moved in, a

neighbourhood

would be identified in government records, and thus on maps, by its

post

office (usually established in the home of a settler) and it's name

became

the community's identity. For instance in a map by DeVille dated 1883

Fairburne

(original spelling), Desford, Adelpha, Alcester, Wakopa and Hayfield

are

identified, while Boissevain, Killarney and Minto have yet to may an

appearance.

[13]

A

quick stop and we're off to the bustling commercial centre of the

region.

Boissevain

By

1906 Boissevain was already a

well-established town on a busy C.P.R.

east-west line. It origins date to 1885 when, in anticipation of the

arrival of the tracks, several settlers congregated on the site.

One of those was George Morton, a well-established businessman with

several ventures in the region, who moved his general store

building from the

earlier settlement of Wabeesh (near present-day Whitewater) which was

to be bypassed. By 1886, with the tracks in place, the little town

inlcuded a grain-loading platform, a post office, two more general

stores, a few boarding houses, two hotels, a blacksmith and a grain

warehouse. Originally known as Cherry Creek the name Boissevain

was chosen to honour A.A. Boissevain, a Dutch financier whose

investment had helped finance the C.P.R. I guess one could say that

really

makes Boissevain a "railroad" town. In a way Boissevain

brought as much to the GN line as the line brought to the community.

It was

the first link with the established Canadian routes, expanding the

opportunities

for each line and for the people of the area.

Until 2008 Boissevain had the

distinction of

being the home to the only surviving

GN station, which saw decades of service as a Highways Department

garage.

There is some

evidence that the station

also featured a garage complete with track so that the engine could be

brought

in for service. Unfortunately, when no use for the building could be

found, the costs

of preservation dictated that the building be torn down, but the

stayionmaster's house still exists as a concrete reminder of the Great

Northern's presence.

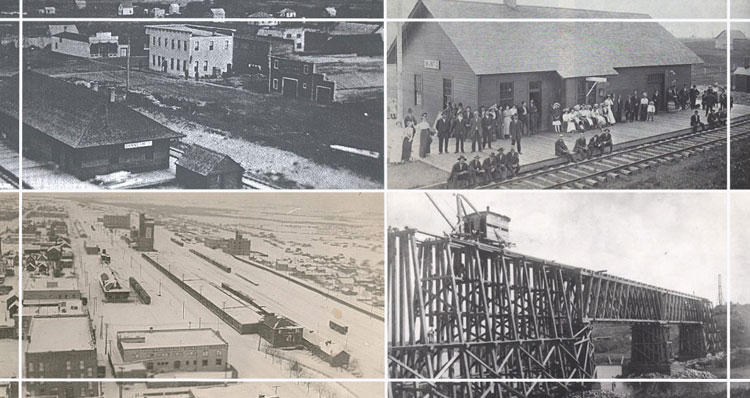

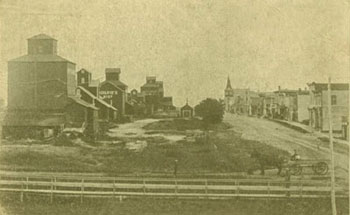

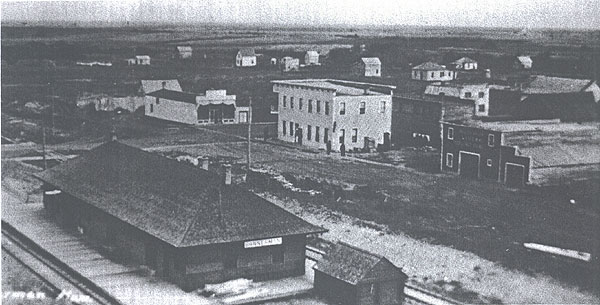

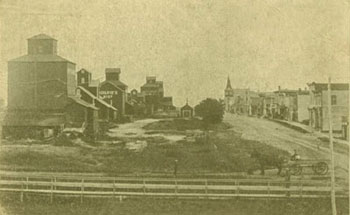

Boissevain

in 1908.

Elevators

along the East-West CN line, The GN line would have run left to

right near the bottom of this image. The station was

a few blocks to the right.

The

GN Station at Boissevain was refitted

for use by the Highways Department (2007)

To an established

centre one immediate benefit was the work available in

construction. There were contracts and jobs available, and the lucky

landowners

who found their farms on the right of way no doubt enjoyed the

compensation.

Even when the line was surveyed right through a house as it was to a

Mr.

Henderson, he happily moved. [14]

A

construction

gang

near Minto.

After a short stop

the whistle blows and we're off again, on our way straight

north to Minto, with a stop at Alcester, another siding and elevator

that

didn't become a town. Alcester had existed as a post office and as one

of

the original "districts" of the settlement era, and the improved

communication

offered by the rail line probably hastened its demise. The post office

closed

in 1907. It was just too close to Boissevain and Minto.

Minto

Although

the

surrounding area was well settled, Minto wasn't established

until the Canadian Northern line in came through in 1898 and a village

sprouted

on the northeastern corner of Section 19-5-10. When a few years later

this

new line, with its links to points north and south, was indeed a shot

in

the arm. The local history is full of examples indicating how happy the

residents

were to get this additional service, allowing convenient day trips to

Brandon

the main trading centre of Western Manitoba.

When

that first train

came through in June of 1906, with daily mail freight

and passenger service to Brandon, life changed. For that period of a

few

decades, the brief but important prairie railway age, there were four

express

trains daily, with the CN going east and west and the GN north and

south.

Added to that was the economic spin-off from the two new elevators and

coal

shed built to serve the line. It was an amazing leap forward from the

pioneer

times when the horse and buggy was luxury travel and people thought

nothing

of walking fifty miles if it had to be done.

Eagerly

awaiting the train for an

excursion

to Brandon Fair, 1917

It was exciting,

as

Sylvia

Sprott indicates in her memoir in the Minto History;

"A trip to Brandon on the Great Northern train was indeed an event to

remember."

Many adventures are associated with the railway are reported in the

local

history. In some winters heavy snowfalls interfered with the schedule.

Snow

clearing equipment wasn't as powerful and fast as it is today, and the

portions

of the line called cuts, where excavation had been used to smooth a

grade

into a valley or over a hill, filled in quickly in a storm. In 1916

heavy

snow cancelled trains for six weeks. In March 16 of 1920 a blizzard

brought

10-15 feet of snow, closed both lines for a week.

And there were other perils. A

daughter

of John

MacDonald reports that, "One

year a spark from the Great Northern train started a fire that burned

most

of the crop, all the buildings, and a great deal of hay." [15]

The

GN line

crossed the CN

line at Minto, a tower overlooked the crossing.

Heaslip

Before the

arrival

of the railway the settlement in the Minto area was defined

by a series or rural Post Offices and the pre-railway cart-trails,

rather

than by a village centre. Samuel A. Heaslip (Pronounced hays-lip) came

from

Ontario in 1881 and homesteaded 32-5-19. just south of the Souris River

and

close to an established route between Brandon and points south. Mrs

Heaslip

was first white woman in district that soon bore their name. Mr.

Heaslip

drove mail after railway came to Brandon in 82. The trail crossed

Souris

at Sheppard's Ferry, passed the Heaslip's home, on to Sheppardvillle at

3-5-20,

then to the Turtle Mountain area. The route soon became known as the

Heaslip

Trail. The Heaslips well known and their home was a stopping place on

the

trial to Brandon. Mrs. Heaslip, widely known as a kind motherly person,

served

as deputy post mistress of the first Post Office of the district.

It

got another big boost when the Great Northern began operations in

1906

and the Heaslip community also developed into the beginnings of a

village,

with a station and general store. At the village's apex in the 1920's

the

store was bought by Otis Vig who moved his family from Bannerman to

these

greener pastures. The direct rail line came in handy for the moving of

household

effects and the family was soon comfortably established in the

residence

above the store, across the tracks from the McCabe Elevator and the one

other

residence, that of Heman Bales the grain buyer, and less than a

kilometer

south of the station and loading platform. Mr. Vig expanded, opening a

Case

Implement Dealership.

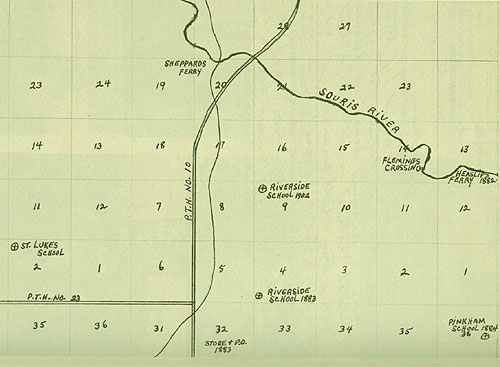

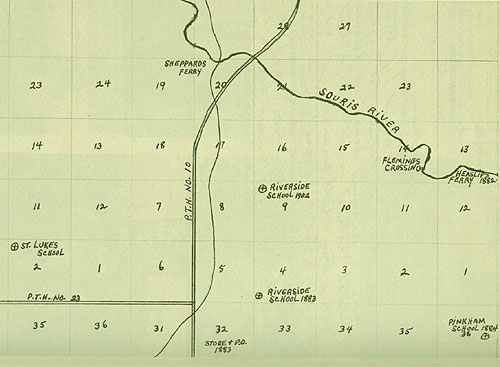

Main routes, before and after the

days

of

the railway.

During this time the

bridge we now call the Old Riverside Bridge was built,

changing the road transportation patterns substantially. Until this

bridge

was built the main road from Brandon south followed the rail line south

from

Brandon, through Hayfield and Bunclody. In the 20's what we know as

Highway#10

was developed and became the main route bypassing those villages. The

age

of the auto was upon us and as the railway had dictated which townsites

survived

in earlier times, the highway was now the key.

Perhaps seeing this

writing on the wall, Mr. Vig sold his store in 1930 and

soon relocated to Brandon. Even had the railways continued to operate,

as

roads improved and cars became popular, Healsip was just one town too

many

on a busy highway. [16]

Heaslip

from the

south

Bunclody

Pulling out of the Heaslip Station the track

bends slightly westward and

passengers who look to the east will see the first real change in

scenery.

The landscape of Southwestern Manitoba is

dominated, perhaps defined, by

the Souris Plains, a wide expanse of relatively flat country stretching

from

the base of the Turtle Mountains west and southwards towards the Souris

River

Valley. Early settlers speak of climbing out of that valley at

Millford,

near where Treesbank is today, and noting the Turtle Mountains to the

distant

south. That's how flat the plains are, it's a distance of nearly 100

kilometres

and to call those turtle-shaped hills mountains was a bit of a stretch.

Today

a drive from Minto west to Elgin, essentially through the centre of the

Souris

Plains, gives one and understanding of the term "wide open spaces".

And then, as now, the traveler new to the

area, and

on a trek from Boissevain

northwards to Brandon, whether on the rutted ox-cart path known as the

Heaslip

trail, or on the smoothly paved Highway 10, might be surprised when,

out

of nowhere, appears the valley of the Souris, a kilometer wide / 70

metre

deep channel cut over ten thousand years ago as the last of the glacial

lakes

drained.

Scenic it may well be, but to the railroad

builder

it holds no romantic charms.

It is an obstacle to be crossed. A challenge perhaps, a nuisance,

definitely.

When building a railway over hills or through

valleys it is often advisable

to the travel a few extra kilometers to avoid a steep grade and the

expensive

construction costs associated with difficult terrain. Trains don't do

well

on hills, and keeping the grade or slope of the track as gentle as

possible

is a priority in construction. As far as the prairies go, the northern

portion

of the Souris River valley is a major challenge. The surveyors for the

Great

Northern had rejected a crossing straight south of Minto where the

valley

is both deep and wide, and had selected a site near the hamlet of

Bunclody

where the southern lip of the valley, although steep, brushed right up

against

the stream, while the gentle slope on the north side could be crossed

with

a modest embankment. To get there, the line bends westward at Heaslip,

following

the curve of the river and crossing a series of deep cuts where ravines

enter

the valley.

This was the major construction

site of the whole

project. Three work camps

were quickly set up, one at the deep ravine 3 kilometres south of the

crossing,

one at the townsite on the south side of the river where the station

house

was built, and one on the north side of the river. Each camp had a

steam

shovel, (“of the largest size”) modern technology not

available a mere 25

years earlier when the CPR crossed Manitoba. Dinky engines were used to

haul

and dump cars as the grade was built up. It was a major engineering

project

undertaken by, “one of the largest railway outfits in

America.” [17]

The ravines south of the river were crossed by

building temporary trestles

and dumping fill to create a road-level earthen dam, complete with huge

pipes

designed to let the runoff through. The pipes soon broke and had to be

replaced

with concrete tunnels two metres square - still quite visible

today,

although somewhat clogged with rubble. One resident told me about

boyhood

adventures that included a dare to go through the tunnel.

Crossing

a

ravine

between

Heaslip and

Bunclody

The site in 2016

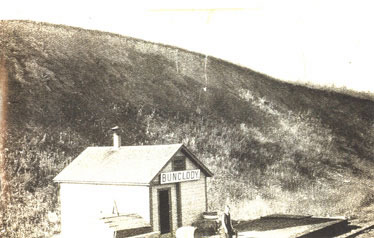

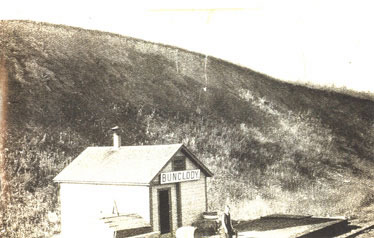

Bunclody

Station

The bridge

over the

Souris was

the

biggest

undertaking. The span was 132m. long and 26m. high. Timber for the

trestles,

including 30 metre long cedar pilings had to be hauled from the CN Rail

stop at Carroll, about 8 kilometres away.

The elevator

and station, along with a

bunkhouse for some of the the many full time employees required to

maintain the line, were situated halfway up the southern ridge of the

valley, half a kilometer from the bridge. The water tank was on the far

side of the river slightly north of the bridge, with pumps and pipes to

draw river water for the steam engines.

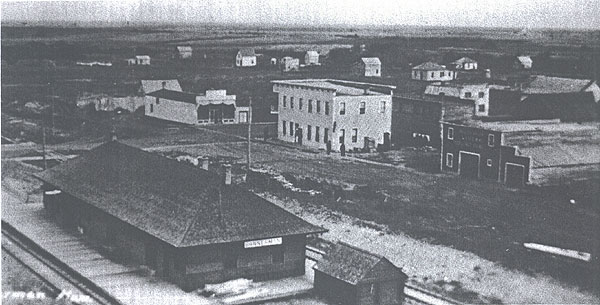

Taken from the hill, SE of

the

elevator.

Preparing the grade

towards

the crossing of the Souris near Bunclody.

Bridge construction

Today,

standing on the old rail line where

it abruptly ends atop a steep cliff at the river's edge, having

followed it from that site through a pasture as it curved towards the

former crossing, one can look northward across the river and see one of

the few remaining obvious signs of the old line. Directly below you, in

the centre of the river is a small gravel bar, once the base of the

central bridge support, and across the river where the valley wall

slopes gently away from the water's edge, is the high embankment built

to carry the line gently across the wide valley.

From

the day

that first train came through

on June of 1906, there were two passenger trains per day, going

south

at 8 a.m. and north at 7 p.m., six days a week. The freight train ran

every day, south on one day, north the next, except Sunday. If one were

to stop at the station and swap railway stories with the locals you'd

likely hear about the time in 1916 when a runaway engine from Minto

stopped at Bunclody. Later in the day the Engineer and fireman came

walking down the track looking for the runaway. It happened when the

engineer thought that a switch was closed at Minto and he and fireman

jumped ship, so to speak. A closed switch would create a dangerous

derailment. It turned out that the switch was in place.

This was not

as uncommon

an

event as one

might expect, there was another incident a year or so later when a

boxcar got away from the Heaslip siding and rolled on downhill to

Bunclody.

Or perhaps

you'd hear

about

the morning

in

1914 when three horses wandered onto the right-of-way. They were

frightened by the approach of the frieight train and ran ahead of it to

the bridge; where they jumped off and met their deaths on the frozen

river 26 metres below.

Here,

as at

other stops on the line, you would

certainly hear the winter tales.

Snow

was the

winter enemy. Trains were stuck

often in cuts sometimes for a considerable stay! The Bunclody History

relates the story of a train stuck in the Hebron cut from November

until March. That was in the first year of operation and it was a work

train which had its own kitchen so the crew lived there for the winter.

It was on the farm of a Mr. Roger, who obliged by hauling them water.

Was this during construction perhaps, because no mentions is made

anywhere of that sort of interruption in service?

Apparently

four metre feet deep drifts in cuts

caused stoppages of up to six weeks in the winter of 1915-16.

Each

winter had its share of such events. In February of 1923 a blizzard

blocked the line from Minto to Brandon for three weeks. Clearing the

snow was a big job, without the advantage of today's high-powered

graders and bulldozers.

The

worst spot

was the Wilson Cut two

kilometres north of Heaslip, the site of an adventure in March of 1923.

A train with two engines and a snowplow was stuck and snow drifted in

half-way up the windows. In such cases, neighboring farmers were often

called upon to

help out and the presumably patient passengers relied on the kindness

of strangers so-to-speak. Supplies were brought from the Heaslip store

and lunch was served.

Hebron

and Griffin

Siding

Sometimes

plans change. On paper it looked like Hayfield was the next logical

station with the potential to become a village. Sidings and/or loading

platforms would be sufficient for the two stops between Bunclody and

that newly established site.

Those

two stops would be Beverly and

Hebron.

Hebron

had

been

an

identifiable

community for some time, with the school as the focal point. Between

the Beverly and Hebron sidings the line was crossed by a busy east-west

CP line connecting Winnipeg and Regina by a route parallel with the

main line. These crossing were referred to as "diamonds" and required

staffing to set the switches. Slightly west of the diamond at Newstead,

a rival company established an elevator and before long the McCabe Co.

and their Great Northern allies determined that they too needed and

elevator at the crossing to compete. This meant having an unprecedented

four elevators on a mere 12 kilometre stretch. It also meant that

Hayfield which had a full station as opposed to a small shelter, would

be downgraded. Its station was moved to the Diamond, named

Griffin. Later it was moved again and served the remainder of its

days as a community hall in the Riverside district a few kilomtres to

the south west. Hayfield received the shelter that had been at Hebron.

Hebron School

From

Bunclody

the line angles a bit west to

skirt the western rim of the Brandon Hills, and at the western foot of

those hills is the hamlet of Hayfield.

Hayfield

is on the early maps, and had a

post office and school serving a defined region. Although surveyed as a

town during the planning of the line, it never did contain much more

than the station, a general store, a hall and a few houses. Today as a

traveler going south

from Brandon who turns westward off of #10 Highway and proceeds

down Hayfield Road will pass the unmarked and unrecognizable townsite.

[19]

Downtown

Hayfield

From

there

the rails

continued straight north

through McKelvie and Roseland before angling eastward into Brandon.

An on to Brandon....

From Hayfield the route takes us

through a siding at McKelvie and the tiny village of Roseland then in

to Brandon.

Brandoin railway historian,

Lawrence Stuckey, remembered

transfers between

the CN

and the Great Northern

on a track set up on what is now 25th street. He also remembered going

down

the main line, which entered Brandon from the west running just south

of Pacific Avenue. The colourful refrigerator cars

carrying

fruit from various American companies especially caught his eye. No

evidence

remains of the wye about 5 kilometres west of the station where

passenger

trains turned around to back into the station, nor of the "diamond

crossing"

over the CNR line a kilometer south of that and the tower overlooking

it.

There was a three-stall engine house and turntable for maintenance near

26th

and Pacific, a station near 11th and Pacific, and a block-long freight

shed

a few blocks west of that. [20]

The Great Northern

contributed substantially to Brandon’s economic makeup.

A promotional publication entitled “Brandon in 1913” boasts

that ”Brandon

has direct connection with the great railway systems of the United

States…”

and goes on to mention that the railway has a charter to build on the

The

Pas and Hudson’s Bay. [21]

Brandon

Station, train ready to depart. They were backed in to the

station area.

Brandon

Station, train ready to depart. They were backed in to the

station area.

It wasn’t without

at least some opposition, but that was mainly related to

issues about the appropriation or re-location of some homes and

buildings

along the route as the rails were pushed into the city. [22]

But the ongoing

battle between the C.P.R. and all

forms of competition was

not over. The C.P.R. responded with a new station and an expansion in

Brandon

that some though was partially intended to ensure “for all time

the exclusion

of any other railway lines along this throughfare such as the

continuation

of the Great Northern through the city.” [23]

The

End of The Line

By

late 20's it was

apparent that big profits for the company would never

materialize. The line had been built into an area that was already

served

by east-west lines. Unlike the original CPR lines, the owners had been

prevented

from making large start-up profits from the establishment of towns and

the

grants of land often associated with a new line. With the defeat of

Laurier

in 1911, the hope of a reciprocity agreement with the US, which would

have

increased north-south freight, was effectively over. The population had

reached

its peak and the car was establishing itself as the mode of choice for

personal

transportation.

This possibility of

reciprocity

had

encouraged the expansion of the Great

Northern and some speculated that it would lead to a large portion of

the

grain harvest being transported through the U.S. Needles to say, there

were

many Canadians opposed to reciprocity for that very reason. The Portage

La

Prairie Weekly noted that “The Great Northern Railway…has

no lees than seventeen

different lines operating between Canada and the country over the

border…:

and could see that much business would go that way. [24] That was

a

pretty good argument against Reciprocity from a western point of view.

Another force at play was the growth of the

cooperative initiative that became

The Manitoba Pool Elevators.

"Part of the problem … was that farmers were

prepared to support the Manitoba

Pool, even at a financial cost to themselves." McCabe had monopoly on

the

GN line, thus there were no Pool Elevators along its route. At one time

Pool

was paying 53 per bushel while McCabe as much as 75. By 1929

losses

had mounted to $74000. In 1935 grain tonnage on the line was only 16.5

%

of what it had been in 1913. [25]

At the same time passenger service fell off.

Although it was never intended

to be the primary source of income, it was helpful to the bottom line.

In

1906 travel by auto was a slow and unreliable. But people really liked

the

freedom the car gave them, and better roads and cheaper, more reliable

vehicles

developed rapidly. By 1922 a "highway" existed from Brandon to

Boissevain

and on to the border. By 1927 rail passenger numbers began to decline.

|

|

By 1930 a bridge

crossed the Souris

northeast of Heaslip

at the point now known as Riverside, and soon the present day Highway

#10

bypassed Hayfield and Bunclody.

The

depression worsened the situation and only

pressure from the government

kept it open until 1936 when the mail contract ended. It was simply not

a

viable enterprise, if it ever was. The tracks torn up in 1937 after

there

were no offer for the purchase of the line. The company formally

continued

to exist until Dec. 12. 1963 to allow for ongoing land transfers.

The

last train ran June 14, 1936. Stuckey

remembered with apparent fondness

the day when he and a friend waved to the engineer for the last time.

[26]

So ended a chapter in the region's

transportation

history. The line is credited

with ending the rural isolation felt by many Westman settlers and

offered

them an important time-saving travel option. Daytime shopping trips to

Brandon

were a treat, students at university could get home for weekends. But

the

car and the improved road conditions offered a new sense of freedom to

rural

residents, and the line, though remembered fondly by old-timers, was

just

not needed any longer.

Rail

lines in southwestern Manitoba. By 1914 virtually all farmers

were

now within 10 km. of an elevator. Withing another 20 years the age of

the auto would herald a new era, and many of the rail lines would

become unprofitable.

|

Bibliography

For more images - go to our

section on the BS&HB Communities

Todd, John, Jim Hill’s Canadian Railway, Canadian Rail No. 283, August

1975, Canadian Railroad Historical Association, Montreal

Download the

pdf..

Everitt, John, Kempthorne, Roberta, Scafer, Charles,

Controlled Aggression: James J. Hill and the Brandon, Saskatchewan and

Hudson’s Bay Railway, Brandon University, 1987, 7

Beckoning Hills Revisited : Ours is a Goodly Heritage,

Morton-Boissevain, 1881-1981, Boissevain History Committee, 1981

391, 523, 524, 593, 594

Minto Memoirs 1881-1979 : History of Minto and District, Minto and

District Historical Society, Inter-Collegiate Press. Winnipeg MB, 1979,

235, 42, 184,

Rose, D.F., Bunclody Community, 1879-1970, Bunclody Community, Carroll

MB.,1970

Memories of Hebron and Riverview, Riverview/Hebron Book Committee

|

|