General Rosser's Legacy

Introduction

This inconspicuous

little article,

which

appeared in the Winnipeg Daily Times on May 16, 1881, is remarkable in

its lack of fanfare when one considers the impact General Rosser's

decision was to have on our province. Both the newspaper editors and

their readers, having witnessed countless tales heralding the next

great prairie metropolis, may be excused for missing the genuine

article here. For what they were witnessing was the birth of Brandon,

Manitoba's second city.

The text of following article was first published by Manitoba History

in its Fall 2007 tribute to Brandon's 125th Anniversary.

What’s

the connection between Rosser Avenue, Brandon’s

“Main” street, and the Rural Municipality of Rosser near

Winnipeg? How about the connection between The Battle of Little Bighorn

and the creation of Manitoba’s second city?

It all starts with the railway. At the beginning of 1881 what we now

call southwestern Manitoba was part of the Northwest Territories, as

the western provincial boundary stretched only slightly past Portage la

Prairie. It was, quite literally, not on the map. Specifically,

it was not on C.P.R. Chief Engineer Sanford Fleming’s map,

dated April 8th, 1880, and submitted as part of his report on possible

rail routes westward. He mentions that that the regions thereabouts had

“so far as known, have not been explored”. [1]

Though perhaps not explored, the territory had been considered in an

abstract way. Mr. Fleming, despite continuing to advocate for a

slightly more northern route along the Little Saskatchewan Valley and

skirting the Riding Mountains to the south, also envisioned a southerly

extension that would cross the Assiniboine near the mouth of the Little

Saskatchewan. He noted the agricultural potential of the region and

that it might become a site for a future city that would “shortly

become important”. [2]

This largely unpopulated area was slowly developing the first tentative

forays into agriculture with the noticeable beginnings of towns seen at

Rapid City, Minnedosa (Tanner’s Crossing), Millford (near the

confluence of the Souris and Assiniboine Rivers), and Grand Valley (a

few kilometers east of Brandon). These locations are mentioned in

the George Wyatt’s 1881 “Guide for Settlers”, which

includes a list of post offices and charts with destinations for both

steamboat and stagecoaches, [3] while the site that would later become

Brandon was an undeveloped homestead.

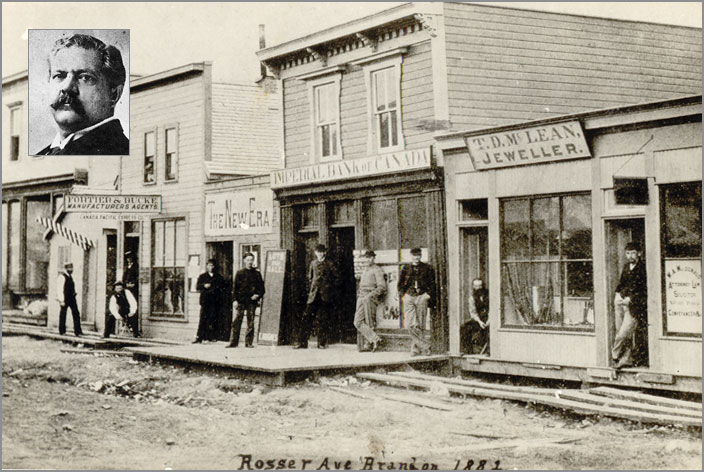

But before the end of 1881 this unassuming patch of riverside prairie

had become a bustling town with hotels, grocery stores, restaurants and

various outfitters popping up like crocuses on the sunny side of a

hill. Now, in any normal prairie town, activity of this sort would be

taking place on Main Street; or on a main street by any of the other

generic names: Front Street, Railway Street, sometimes even Commercial

Avenue. Even Winnipeg has a Main Street.

Winnipeg

Times,Nov. 15,

1881

Winnipeg

Times,Nov. 15,

1881

But

Brandon, instead, has Rosser Avenue and it was named after the

C.P.R.‘s Chief Engineer who established the site: Thomas

Lafayette Rosser. That’s a considerably enduring tribute

considering that the man worked for the C.P.R for less than a year and

departed in the midst of accusations, recriminations and scandal.

And also considering that lesser avenues bear the names of two of

Rosser’s bosses, Van Horne and Stickney.

But then Rosser was not your ordinary railroad engineer. In fact, it is

proper to refer to him as General Rosser, an American no less,

southerner even, and a well-respected veteran of the American Civil War.

That said, the man liked naming things and in his short time in our

province invoked his admiration for fellow countryman Stonewall Jackson

by bestowing that name on an upstart town just north of Winnipeg and

had his own name attached to a village and a municipality also near

that city. He even had the village of Griswold, near Brandon, named

after one of his American friends. [4] You might say that he left his

mark.

In the spring of 1881 this former soldier, well into his second career

as a Railway Chief Engineer, crossed the Assiniboine River at a point

about 200 kilometres west of Winnipeg, bargained briefly with a Mr.

Adamson and purchased the townsite of Brandon for little more than a

song. As with many other deals struck in the creation of railway towns

in the era, potential profit for Mr. Rosser was a consideration [5].

He’d just rejected the site known as Grand Valley, the

area’s most well-established settlement, a few kilometers

downriver in a famous confrontation with area pioneer John McVicar, who

had his own notions about profit.

Winnipeg

Daily Times

July

12, 1881

Winnipeg

Daily Times

July

12, 1881

The story of

the founding of Brandon has often been told, in its various and

conflicting forms. Where does fact give way to legend? Do we believe

Mrs. Dougald McVIcar. sister-in-law of the Grand Valley property owner,

who makes no mention of Rosser’s offer to purchase the town site.

[6] How reliable are the various other accounts that have McVicar

falling victim of bad advice from cronies? What about Brandon pioneer

Beecham Trotter’s account wherein McVicar immediately asks for

double what Rosser was willing to pay, only to be stung by

Rosser’s, equally quick reply, ”I’ll be damned if a

town of any kind is ever built here.” [7] The most reliable

account may be found in the memoirs of James Secretan, a C.P.R.

surveyor who worked with Rosser. He recalls that Rosser indeed made a

$25000 offer, and when McVicar did counter with a request for $50000,

the General abruptly ended negotiations and moved on upstream. [8]

Upon taking the suggestion of the captain of the prairie steamboat the

Marquette, and naming the city Brandon in a nod to the nearby hills and

former HBC post, he set about putting his stamp on the community. It

was General Rosser who ordered the surveyor Mr. M. P. Hawley to keep

the lots of the new city small, and the streets narrow (66 ft as

opposed to 99) - more profit was the first concern. [9]

If this and other decisions benefited Rosser, one must also acknowledge

the benefit to both his employer the C.P.R. and to the public.

His policy of avoiding established towns, first evidenced in the Grand

Valley episode, saved a fortune. The decision to establish the C.P.R.

headquarters in Winnipeg was a sensible business decision and certainly

good for Manitoba, and of all the decision he made, his selection of

the site of Brandon has had the most lasting impact.

Who exactly was this “General Rosser”? There seemed to be a

lot of Generals and Colonels involved in the opening of the west.

According to one of his surveyors, James Secretan, whom Rosser

appointed to take charge of the line west, he was ”…

a most lovable man… a tall, handsome, swarthy Southern gentleman

of the real old type, had fought in the ‘late

unpleasantness,’” [10] Biographer Thomas Beane

referred to him as “a superb horseman, tall and muscular, with a

firm jaw and a manner that exuded self-confidence.” [11]

He was, in

fact, a Confederate Major General of Cavalry during the American Civil

promoted to command by Confederate Army leader J.E.B. Stuart who cited

his leadership, bravery and tactical ability. [12] That’s a

pretty good resume, but on the other hand, biographers also note that

he was a man driven by a quest for financial gain, and a person who

could be “arrogant, aggressive, racist, and proud to a

fault.” [13]

There is general agreement that, in an age when many self-important

people tended to attach questionable military ranks to their identity,

Mr. Rosser, in fact had earned his rank in battle.

He was indeed complex person, and undeniably, one with many talents and

a wide variety of experiences. The two key aspects of his

character: his almost ruthless, action-oriented approach to getting a

job done, and his ever-present eye on the possibilities for profit, are

amply demonstrated through his actions during his short time with the

C.P.R.

It turns out that this authentic Confederate General was also a

West Point classmate and friend of the illustrious General Custer, he

of Little Bigfoot fame. It reminds one that the west was indeed a small

place in those days and that, especially in this region, history

intertwined often on a north-south axis regardless of borders. How did

a Confederate General end up in Grand Valley as advance man for our

national dream?

Rosser, who was born in Virginia in 1836, spent his youth on the Sabine

River near the Texas-Louisiana border before entering West Point in

1856. Just weeks before graduation, the outbreak of the Civil War

caused him to skip that formality and head home to enlist the new

Confederate Army. His colleague and friend, George Armstrong Custer,

class clown and all-round hell-raiser, being from the north was able to

stay on and finish.

Lieutenant Rosser soon distinguished himself as a cavalry officer, and

moved up the ranks quickly. Superiors, in particular, noticed his

calmness under fire and his ability to mould groups of raw recruits

into an efficient fighting machine. He was a perfectionist who took

great pride in his accomplishments.

From all reports he developed a flair for the dramatic. Perhaps

he had taken to reading his own press. Describing a difficult situation

during the turning point Gettysburg campaign he later reported: "The

enemy greatly outnumbering us, appeared in force everywhere, and it

became apparent that victory was the only means of escape." [14]

And escape he

did,

and although the war continued to go badly for the South, and Rosser

himself sustained several serious injuries, he continued to be a

formidable presence, harassing the Union forces wherever he encountered

them, capturing supplies, never avoiding a fight. [15] In fact he was

so successful that the Union commander General Sherman ordered one of

his young up-and-comers, George Custer to deal with his former

classmate. Thus began a series of engagements and a gentlemanly rivalry.

General

Rosser in Uniform

A now famous battle against Custer at Tom’s

Brook (Oct 8,1864) in

the Shenandoah Valley saw Custer with his customary flare for the

dramatic, or perhaps mere gentlemanly courtesy, ride between the lines

before the onset of hostilities and deliver a gracious low bow to his

worthy opponent. Rosser acknowledged the gesture with a smile and

explained to his staff, “You see that Yank down there

bowing? Well that’s General Custer, the Yanks are so proud of,

and I’m going to give him the best whipping he ever got”.

[16] It wasn’t to be. Custer easily prevailed this day in a

contest later dubbed the “Battle of the Woodstock Races”.

The moment, like so many in Custer’s career has been recorded for

posterity in a drawing.

Custer, at one point, was fortunate enough to be able to capture

Rosser’s luggage complete with a uniform. He wrote his friend

thanking him for the wardrobe addition and suggesting that Rosser have

his tailor make the coattails of his next uniforms a little shorter to

accommodate his (Custer’s) shorter stature. [17]

As we all know, it was in a losing cause. But Rosser wasn’t

inclined to “cut and run” as they say today. He earned

himself a place in the history books, and perhaps some grudging respect

from the victors for refusing to surrender his unit when everyone else

could see it was all over.

With his military career cut short by the end of the Confederacy,

Rosser, with scant success, tried various job and business enterprises

until in1869, like so many others, he headed west. There he landed a

“starting level” position with a small railway concern and

quickly established himself in this the growth industry of the

mid-nineteenth century. [18] The building of railways across the

“untamed” west offered travel and adventure, even a bit of

danger. It was almost as good as the army! And Rosser rose just

as quickly. Starting at the bottom he worked his way from roadman, to

scout, chief surveyor and, soon enough, Chief Engineer of the Northern

Pacific Railway. [19]

As he engaged in the task of surveying the line westward through

Montana there was some resistance and harassment from the local

inhabitants the Sioux, who for good reason didn’t trust the

intentions behind this intrusion into what they had every reason to

suppose was their home. To the rescue came old friend Custer, who,

being on the winning side of the recent north-south conflict,

hadn’t had to give up his profession. The victorious North

hadn’t waited too long for a new enemy to appear and what we

charitably refer to as the Indian Wars was underway, with Custer as a

central figure.

George

Armstrong Custer

Classmate, rival, and

friend of General Rosser.

This

military-railway collaboration was perhaps the first of what some would

insist became a trend in the U.S.; the use of military force to back

the interests of large corporations whose endeavors are identified with

the natural interest. It didn’t do much for relations with the

west’s natives.

The meeting of Rosser and Custer in a camp on the Northern Pacific line

must have been like a reunion of old friends. They no doubt recounted

old times and those see-saw series of battles and skirmishes along the

Shenandoah Valley and the exchange of notes and friendly jibes. [ 20 ]

Rosser’s friendship for Custer was perhaps most famously

displayed after Custer’s demise at Little Bighorn. With the

Custer legacy under attack, and the President himself beginning to lay

blame, Rosser jumped to the defense of his former adversary. In a

letter to the Chicago Tribune he puts the blame for the disaster on the

shoulders of Custer’s subordinates:

“I feel that Custer would have succeeded had Reno with all

the reserve of seven companies passed through and joined Custer after

the first repulse. I think it quite certain that General Custer had

agreed with Reno upon a place of junction in case of a repulse of

either or both of the detachments, and instead of an effort being made

by Reno for such a junction as soon as he encountered heavy resistance

he took refuge in the hills, and abandoned Custer and his gallant

comrades to their fate.

As a soldier I would sooner today lie in the grave of General Custer

and his gallant comrades alone in that distant wilderness, that when

the last trumpet sounds I could rise to judgment from my post of duty,

than to live in the place of the survivors of the siege on the

hills.” [21]

The

Winnipeg Daily Times, May 1, 1881

Rosser was soon

forced to retract his impetuous attack on Reno, under threat of

lawsuit, [22] but his spirited defense of Custer, aside from accurately

highlighting a central point of a fascinating controversy, is

indicative of a relationship that is much easier to understand when

taken in the context of the times. The Civil War provided countless

stories of close friends and even family members taking opposite sides.

In any case Rosser and Custer made a good team, and the survey into

Montana was a particularly dangerous operation. Rosser himself usually

carried a rifle, a brace of pistols, and saddle bags full of ammunition

when traveling and once had occasion to use his weapons in a stand-off

with Sioux who had just killed his co-worker and friend. [23]

At that time, James Jerome Hill, a former Canadian based in St. Paul,

Minnesota, was the president of the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba

Railway, a company he had taken over at the verge of bankruptcy and

turned into a gold mine. [24] By 1881 he was a member of the Montreal

syndicate with the first C.P.R. contract, something he had at first

undertaken with the hope of uniting it with the lines south of the

border, thus creating the beginnings of a western transportation

empire. At that time many thought that an all-Canadian route,

north of the Great Lakes, through the Canadian Shield was neither

advisable, nor economically feasible. The logical route was to go south

of the lakes, through the United States, and through Pembina and on to

Selkirk. Logical that is, if from a Canadian perspective, one forgets

the political implications; or from the American perspective, one fully

expects the US to control the entire west in any case. In the meantime,

Mr. Hill was a man with a track record and when he needed someone to

solve problems in the operations north of the border he called on

Rosser.

Thomas L.

Rosser in the

1870's

And what was in it for

Rosser? A reasonable salary, to be sure, the

element of challenge and fact that Rosser had worked with Hill briefly

on the “Manitoba Road”, were all factors. [25] But there

was also the tacit understanding that it wouldn’t be totally out

of line to use one’s influence and inside information to make a

few extra bucks. At least that’s the way Rosser seemed to

see it.

The establishment of a railway in undeveloped country is the original

ground floor opportunity for a venture capitalist. The laying of the

rails is the first step in the creation of the new map of the area.

Everything rides on a few key decisions. The locations of the general

route, specific route, divisional points and sidings all determine the

location of towns. The growth of those towns depends largely on the

railways use of that town. Divisional points, located about every 300

kilometres will be major supply centres, while stations or sidings will

be less important. Either way, railway decisions will be the key

determinant of land values in a given settlement.

Google

Earth

Rosser had been

through all this before with The Northern Pacific. He had been

responsible for selecting townsites, and crossings – in fact his

selection of crossing of the Red River at Fargo, and the land

speculation profits he is assumed to have garnered, was the beginning

of his personal fortune. [ 26 ]

Originally the C.P.R. was to cross the Red at Selkirk, a preferred

crossing in that the area near Fort Garry at the forks of the

Assiniboine and Red was prone to flooding and that the route was then

to follow the flat, easily-crossed area we now call the Interlake,

through the narrows of Lake Manitoba and northwest towards the

Saskatchewan River. The Carleton Trail, already in use for

decades, followed the Saskatchewan River to Edmonton, and from there

the Rockies were to be breached at the Yellowhead Pass.

The choice of this route was based on exhaustive research by two

extensive exploratory expeditions. John Palliser, an Irish gentleman

adventurer, who had already traveled widely in the American West was

selected by the Royal Geographical Society and the Imperial Government

to explore the area between Lakes Superior and the Rockies and report

on everything from plant species to possible travel routes. After a

two-year field trip he concluded that the only good land in the area

lay in a belt along the North Saskatchewan. In fact the vast area

comprising the southern third of Saskatchewan and Alberta, now called

Palliser’s Triangle, was deemed thoroughly unsuited to

agriculture. [27]

Another expedition, sponsored by Canada and lead By Henry Youle Hind, a

geology professor from Toronto, came to similar conclusions. There was,

apparently, no real future for the southern prairies. Normally,

railways are built where the customers are. In this case the railways

came before the customers, so it was a case of deciding where the

customers would end up.

And that’s the way it stood when General Rosser rode into the

picture in the spring of 1881. He was at the table, when James Hill and

the Executive Committee of the C.P.R. changed the history of the

Canadian West. In short order they decided that the route across the

prairies, instead of following the northern route would take a much

more southern route, essentially where it now exists through Brandon,

Regina, Calgary and the Kicking Horse Pass. As to the reason for

this dramatic reversal of policy, one theory is that it all turned on

the work of one man, John Macoun. For he too was at that famous

meeting. [28]

Macoun had

accompanied Sanford Fleming on his first survey of the Carleton Trail

route ten years earlier, and returned for extensive research in 1879

and 1880. His observations were that the southern prairies were indeed

well situated for agriculture. Now we know that the reason for the

differing points of view are a simple as the cycle of drought normal to

this prairies region. Palliser and Hind made their observations in

1857-59, the centre of a dry spell. Macoun in 1879 and 1880 witnessed

the wettest years of the century. [29]

The decision, or more significantly, its approval by the government,

may also have rested on a few other foundations. Politically it was

advisable to located closer to the American border to preempt possible

competition from an American line and to keep a firm grip on the

territory at a time when many prominent Americans viewed the annexation

of the west by the US as not only desirable, but inevitable. On a more

practical note we were probably seeing the beginnings of the

C.P.R’s policy of avoiding high prices and land speculation by

bypassing expected routes and established communities. They truly were

doing the unexpected in this case. Additionally the southern route was

shorter and would be (they thought!) less expensive to build. Some have

speculated Mr. Hill saw the possibility of some arrangement whereby his

other venture the Great Northern in the U.S. would benefit from some

arrangements with the C.P.R. [30]

So it was that in early May

of 1881 we find Rosser at the end of the

line near Portage La Prairie turning the sod to start what would be a

season of frantic activity for the largely uninhabited stretch of

prairie to the west. As they proceeded, General Rosser and his

boss, Alpheus B. Stickney quickly found that creating new towns was

also more profitable for them personally than using already existing

ones. It was a short-lived relationship, but various reports have

the pair making $130000 between them during their brief careers with

the C.P.R. Not a bad haul in 1881 dollars. [31]. As an example of

what could be done, Rosser was suspected of having had the preliminary

survey of the line in Saskatchewan altered to bring in through present

day Regina where he had invested. [32]

They made a lot of money, but it did not go unnoticed. The local press,

especially in existing centres where hopes and speculations were dashed

by C.P.R. decisions, raised a hue and cry and almost before it began,

Rosser’s career as a railway entrepreneur was over.

First, Stickney was replaced by William Cornelius Van Horne. Perhaps it

was the bad press, or perhaps he actually was alarmed at the

Rosser/Stickney speculations, but one of Van Horne’s first acts

was to dash of a telegram firing Rosser. Rosser deemed it an

inconvenient time to be sacked, ignored the message, and left town on

urgent business. Van Horne again asked Rosser to resign. Lawsuits and

harsh words ensued. In a famous incident in a Winnipeg club pistols

were produced and only the intervention of friends prevented bloodshed.

[33]

Macoun had

accompanied Sanford Fleming on his first survey of the Carleton Trail

route ten years earlier, and returned for extensive research in 1879

and 1880. His observations were that the southern prairies were indeed

well situated for agriculture. Now we know that the reason for the

differing points of view are a simple as the cycle of drought normal to

this prairies region. Palliser and Hind made their observations in

1857-59, the centre of a dry spell. Macoun in 1879 and 1880 witnessed

the wettest years of the century. [29]

The decision, or more significantly, its approval by the government,

may also have rested on a few other foundations. Politically it was

advisable to located closer to the American border to preempt possible

competition from an American line and to keep a firm grip on the

territory at a time when many prominent Americans viewed the annexation

of the west by the US as not only desirable, but inevitable. On a more

practical note we were probably seeing the beginnings of the

C.P.R’s policy of avoiding high prices and land speculation by

bypassing expected routes and established communities. They truly were

doing the unexpected in this case. Additionally the southern route was

shorter and would be (they thought!) less expensive to build. Some have

speculated Mr. Hill saw the possibility of some arrangement whereby his

other venture the Great Northern in the U.S. would benefit from some

arrangements with the C.P.R. [30]

So it was that in early May of 1881 we find Rosser at the end of the

line near Portage La Prairie turning the sod to start what would be a

season of frantic activity for the largely uninhabited stretch of

prairie to the west. As they proceeded, General Rosser and his

boss, Alpheus B. Stickney quickly found that creating new towns was

also more profitable for them personally than using already existing

ones. It was a short-lived relationship, but various reports have

the pair making $130000 between them during their brief careers with

the C.P.R. Not a bad haul in 1881 dollars. [31]. As an example of

what could be done, Rosser was suspected of having had the preliminary

survey of the line in Saskatchewan altered to bring in through present

day Regina where he had invested. [32]

They made a lot of money, but it did not go unnoticed. The local press,

especially in existing centres where hopes and speculations were dashed

by C.P.R. decisions, raised a hue and cry and almost before it began,

Rosser’s career as a railway entrepreneur was over.

First, Stickney was replaced by William Cornelius Van Horne. Perhaps it

was the bad press, or perhaps he actually was alarmed at the

Rosser/Stickney speculations, but one of Van Horne’s first acts

was to dash of a telegram firing Rosser. Rosser deemed it an

inconvenient time to be sacked, ignored the message, and left town on

urgent business. Van Horne again asked Rosser to resign. Lawsuits and

harsh words ensued. In a famous incident in a Winnipeg club pistols

were produced and only the intervention of friends prevented bloodshed.

[33]

Winnipeg

Daily Sun. Juily 13, 1882

Winnipeg

Daily Sun. Juily 13, 1882

The end result

was that Rosser sued for malicious prosecution, asking for $20000 and

getting $2600, [34] then took his “earnings” home to

Virginia where he dabbled in farming and in a succession of imaginative

business ventures that never seemed to make it past the planning stage.

By the 1890’s he was the most prominent living Civil War veteran,

now slipping into the role of American Patriot. He did get one more

shot at a military career, this time as trainer of recruits for the

Spanish-American War in 1898. At the time his death in 1910 he was

Postmaster of Charlottesville, Virginia, a political appointment he had

secured in 1905. [35)

And here in Canada, his legacy is mixed, or worse still, unconsidered.

By most standards, his accomplishments are noteworthy. In that

crucial summer of 1881, when the laying of the tracks set in motion the

pattern settlement would take, Rosser certainly tackled the task at

hand. Supplies were purchased and delivered, men were hired, supervised

and provided with food, towns were created. As Beecham Trotter, who

worked on the railways that summer, so aptly noted in his account of

the times, it was all done with the focus being the day-to-day, no one

being overly conscious that history was being made. [36] There

were lines to grade, bridges to be built and deals to be made.

So, tempted as we may be to find fault with some of General

Rosser’s healthy regard for his own financial self-interest, we

should examine his record through the lens of time and

circumstance. To this day it is difficult to find fault with

Rosser’s decisions regarding town sites, even if they also

benefited him personally, and his work in pushing the rails westward

during the summer of 1881 has perhaps not been fully recognized for

what it was; a job very well done.

Conclusion

No details were provided for these items in the Winnipeg paper, but one

gets the message.

Winnipeg

Daily Times, June

14, 1882

Winnipeg

Daily Times, June

14, 1882

Winnipeg

Daily Times, May 7, 1883

Winnipeg

Daily Times, May 7, 1883

Bibliography

1. Fleming, Sandford, C.M.G., Report : Canadian Pacific Railway 1880,

(Ottawa,: Maclean, Roger & Co.1880), Appendix 15, 248. (The map

referred to is Plate 7 on page 232)

2. Fleming, Sandford, C.M.G., Report : Canadian Pacific Railway 1880,

248.

3. Wyatt, George H. A reliable guide for settlers, travellers

& investors in the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba and the new

North-West (Toronto) 1881, 3-4

4. Alpheus B. Stickney (1840-1916) an American with extensive

experience in railroad construction, who, like Rosser had worked with

J.J.Hil on his St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railway, was

appointed General Superintendent of the C.P.R. in April of 1881 and was

Rosser’s immediate superior. He resigned in October of that same

year amid accusations that he was speculating on Manitoba properties

based on his knowledge of routes.

Manitoba History Biographies, Alpheus Beede Stickney (1840-1916)

http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/people/stickney_ab.shtml

5. William Cornelius Van Horne (1843-1915) was hired as general manager

of the C.P.R. by J.J. Hill in the fall of 1881, replacing A.B.

Stickney. Van Horne, an American who left his post as the general

manager of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad to take on the

Canadian position, is generally credited with providing the leadership

and drive required to finish C.P.R. line across the Prairies and

through the Rockies. Berton, Pierre The Last Spike, 44 : Lavallee,

Omer, John M. Egan, A Railway Officer in Winnipeg, 1882-1886:

An account of Canadian Pacific’s first years in the Manitoba

capital, MHS Transactions, Series 3, Number 33, 1976-77 Season

6. Rudnyckyj, J.B., Manitoba Mosaic of Place Names, (Winnipeg MB,

Canadian Institute of Onomastic Sciences), 89; Geographical Names of

Manitoba, (Manitoba Conservation Winnipeg, 2000); Sources offer no

details about Mr. and Mrs. Griswold or their relationship with Rosser.

7. Van Rhyn, M. (1998). An American warrior Thomas Lafayette Rosser

1836-1910 (Thesis (M.A.)--University of Nebraska—Lincoln), 1998,

79.

8. McVicar, Mrs. Dougald, Reminiscenses of early Brandon (Unpublished

Memoir, 1946)

9. Trotter, Beecham, A Horseman and The West (Toronto: Macmillan

Company of Canada Ltd., 1925), 89

10. Secretan, James Henry Edward,Canada's great highway: From the first

stake to the last spike (Ottawa: Thorburn & Abbott, 1924), 125-128;

Berton. Pierre, The Last Spike (Toronto: McLelland and Stewart

Ltd., Toronto 1974), 25; Berton relates conflicting accounts by J.H.E.

Secretan, a CPR surveyor and memoirs of Charles Aeneas Shaw, a

“locating engineer”; Doerksen, A. D., The Brandon

Wheat Kings - 1887 Vintage (Manitoba Pageant, Winter 1977, Volume 22,

Number 1) favours the account of Trotter. The evidence indicates,

at the very lweast, a lost oportunity for McVicar and the Grand

Valley speculators.

11. Berton. Pierre, The Last Spike, 29

12. Secretan, James Henry EdwardCanada's great highway: From the first

stake to the last spike), 88

13. Beane, T. O. Thomas Lafayette Rosser, soldier, railroad

builder, politician, businessman (1836-1910) (Thesis (M.A.)--University

of Virginia, 1957), 23

14. Beane, T. O. Thomas Lafayette Rosser, soldier, railroad

builder, politician, businessman (1836-1910) (Thesis (M.A.)--University

of Virginia, 1957), 53

15. Van Rhyn, M., An American warrior Thomas Lafayette Rosser

1836-1910., iv

16. Minor, David, “Under Two Flags”, Eagles Byte Research

http://home.eznet.net/~dminor/O&E988.html

August 1998 No. 32

17. Beane, T. O.. Thomas Lafayette Rosser, soldier, railroad builder,

politician, businessman (1836-1910), 40-48

18. Beane, T. O. (1957). Thomas Lafayette Rosser, soldier, railroad

builder, politician, businessman (1836-1910). 44

19. Minor, David, Under Two Flags

20. Beane, T. O., Thomas Lafayette Rosser, soldier, railroad builder,

politician, businessman (1836-1910)). 55-57

21. Van Rhyn, M., An American warrior Thomas Lafayette Rosser

1836-1910. 78

22. Beane, T. O., Thomas Lafayette Rosser, soldier, railroad builder,

politician, businessman (1836-1910)). 60

23. From a letter by General T. L. Rosser, to the Chicago Tribune

(8th July, 1876). (Also cited in Boots and Saddles)

24. Van Rhyn, M., An American warrior Thomas Lafayette Rosser

1836-1910, 95

25. Van Rhyn, M., An American warrior Thomas Lafayette Rosser

1836-1910, 87

26. Berton, Pierre, The National Dream (Penguin Books

Canada,1989), 406-407

27. Cruise, David and Griffiths, Alison, Lords of the Line

(Markham: Penguin Books Canada Ltd., 1988), 129

28. Beane, T. O., Thomas Lafayette Rosser, soldier, railroad builder,

politician, businessman (1836-1910), 57

29. Berton. Pierre,The Last Spike, 14

30.

Macoun, John, Autobiography of John Macoun, M.A.: Canadian explorer and

naturalist, assistant director and naturalist to the Geological Survey

of Canada, 1831-1920 (Ottawa, 1922), 183,184

31. Berton. Pierre, The Last Spike, 11-12

32. Cruise, David and Griffiths, Alison, Lords of the Line, 101

33. Cruise, David and Griffiths, Alison, Lords of the Line, 129

34. Berton. Pierre, The Last Spike, 113 Berton lists no specific no

source for his belief.

35. Cruise, David and Griffiths, Alison, Lords of the Line, 130;

Berton, The Last Spike, 91; Both Berton and Cruise & Griffiths draw

the account from the Winnipeg Sun, July 13, 1882

36. Berton. Pierre, The Last Spike, 91 Berton

37. Beane, T. O., Thomas Lafayette Rosser, soldier, railroad builder,

politician, businessman (1836-1910)). 81

38. Trotter, Beecham, A Horseman and The West, 102

General References and Suggested Reading

Barker, G.F., Brandon: A City (Self-Published, 1977)

Beane, T. O. Thomas Lafayette Rosser, soldier, railroad builder,

politician, businessman (1836-1910) (Thesis (M.A.)--University of

Virginia, 1957)

Berton, Pierre, The National Dream (Penguin Books Canada,1989)

Berton, Pierre, The Last Spike (Toronto: McLelland and Stewart

Ltd., 1971)

Brown, Roy, The Brandon Hill Connection, (Tourism Unlimited, Brandon

MB.)

Brown, Roy, The Fort Brandon Story, (Tourism Unlimited, 158 8th St.

Brandon Mb.)

Brown, Roy, Steamboats on the Assiniboine, (Tourism Unlimited, Brandon

MB)

Coates, Ken, and McGuiness, Fred, Manitoba : The Province and

People (Hurtig Publishers, Edmonton, 1987)

Coates, Ken, and McGuiness, Fred, The Keystone Province : An

Illustrated History of Manitoba Enterprise (Windsor Publications,

1988)

Connell, Evan, S. Son of the Morning Star; Custer and the Little

Bighorn, (Harper Perennial, New York, 1985)

Cruise, David and Griffiths, Alison, Lords of the Line (Markham:

Penguin Books Canada Ltd., 1988)

Custer, E.B., Boots and Saddles or, Life in Dakota with General Custer.

Scituate, Mass: Digital Scanning 1999,

Fleming, Sandford, C.M.G., Report : Canadian Pacific Railway 1880,

(Ottawa,: Maclean, Roger & Co.1880)

Gibbon, John Murray L., The Romantic History of the Canadian Pacific,

(Tudot Publishing Company, New York, 1937)

Hutton, Andrew (Ed.),The Custer Reader, (U of Nebraska Press 1992)

Lavallee, Omer, John M. Egan, A Railway Officer in Winnipeg, 1882-1886:

An account of Canadian Pacific’s first

years in the Manitoba

capital, MHS Transactions, Series 3, Number 33, 1976-77 Season

Macoun, John, Autobiography of John Macoun, M.A.: Canadian explorer and

naturalist, assistant director and naturalist to the Geological Survey

of Canada, 1831-1920 (Ottawa, 1922)

Also at: http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/4612.html

Manitoba Conservation, Geographical Names of Manitoba, Winnipeg, 2000

Manitoba History Biographies, Alpheus Beede Stickney (1840-1916)

http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/people/stickney_ab.shtml

McVicar, Mrs. Dougald, Reminiscences of early Brandon (Self-Published)

Morton, W.L., Manitoba : A History, (University of Toronto Press, 1957)

Kavanagh, Martin, The Assiniboine Basin, (The Gresham Press, Old

Woking, Surrey, England 1966 Ed.)

Secretan, J.H.E., Canada’s Great Highway: From the First Stake to

the Last Spike (London, 1924)

Also at:http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/4949.html

Steen & Boyce. Brandon, Manitoba, Canada, and her industries

(Winnipeg: Steen & Boyce, 1882)

Trotter, Beecham, A Horseman and The West (Toronto: Macmillan

Company of Canada Ltd., 1925)

Van Rhyn, M., An American warrior Thomas Lafayette Rosser 1836-1910

(Thesis (M.A.)--University of Nebraska--Lincoln, 1998)

Welsted, John, Everitt, John, And Stadel, Christoph : The Geography of

Manitoba : Its Land and People (University of Manitoba Press)

Wheeler, Richard S. An Obituary for Major Reno, (Tom Doherty Associates

Book, New York, 2004)

Wyatt, George H. A reliable guide for settlers, travellers &

investors in the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba and the new

North-West (Toronto: s.n., 1881.)

http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/1021.html

|