10: Where is Bunclody?

I’m pretty sure that the first time I ever heard of

Bunclody, someone

was making fun of the name. It was Vince Dodds, the morning man on our

local (Brandon) radio station, and he had a running bit involving

checking in on the exploits of the Bunclody Bridge Marching Band.

Something like that, a gentle comment about small town life at a time

when small towns were rapidly disappearing. It's a pleasant name, Irish

in origin, and, yes, perhaps a bit fanciful when compared to the nearby

communities - with their bland, sensible names like Hayfield, Carroll,

or Brandon.

In any

case, the name must have impressed me enough to remember it, but

not enough to prompt a visit for many years.

It

wasn’t until decades later while scouting canoe trips on the Souris

River that I made my first visit. Bridges are all-important when

planning paddling day trips, that's where one finds the most

user-friendly access to the river, and I soon became acquainted with

all such points in western Manitoba.

What a

treat it was to finally see the place. Yes, you could see why

the radio jokester had singled it out. By the sixties many former

prairie villages were that in name only. It was as if we were reluctant

to take down the road signs, change the road maps and admit defeat.

Bunclody turned out to be just a shady roadside park nestled alongside

a gravel road near the river where it brushed against the southern rim

of a wide valley. It barely qualified as a ghost town! At first glance

only the two cairns in the park, and one residence across from it, gave

evidence of any habitation, past or present.

It's

funny how you can miss things, and odd that in driving through the

valley I didn't notice the way the road southward up out of the valley

cut through a narrow ridge running along the hillside. Not so odd

perhaps that on several trips up the gentle slope northwards from the

river, I failed to notice the signs of a substantial embankment

approaching the river a kilometres to the east; unmistakable evidence

of a railway line. It's obvious if you know what you're looking for,

but a quite unobtrusive element of the rolling valley landform if you

don't. And its quite understandable that later, as I paddled downstream

from Souris to where our vehicle was waiting by the Bunclody Bridge, I

failed to notice the same embankment curtailed on either side of the

river. The constant erosion of a riverbank over a few decades had

erased much of the evidence.

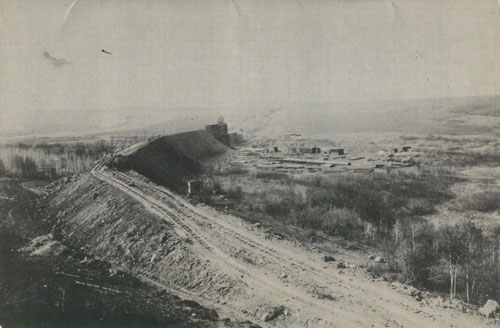

Can you

spot the rail line embankment, along the centre

of this photo?

Today a

drive from Minto west to Elgin, or north to Boissevain,

essentially through the eastern reaches of the Souris Plains, gives one

an understanding of the term "wide open spaces".

Then,

as now, the traveler new to the area, and on a trek from

Boissevain northwards to Brandon, whether on the rutted ox-cart path

known as the Heaslip Trail, or on the smoothly paved Highway 10, might

be surprised when, out of nowhere, the valley of the Souris River

appears, a kilometer wide / 70 metre deep channel cut over ten thousand

years ago as the last of the glacial lakes drained.

Scenic

it may well be, but to the railroad builder it holds no romantic

charms. It is an obstacle to be crossed. A challenge perhaps, a

nuisance, definitely.

When

building a railway over hills or through valleys it is often

advisable to the travel a few extra kilometers to avoid a steep grade

and the expensive construction costs associated with difficult terrain.

Trains don't do well on hills, and keeping the grade or slope of the

track as gentle as possible is a priority in construction. As far as

the prairies go, the northern portion of the Souris River valley is a

major challenge.

In 1904

and 1905 the Great Northern survey crews were at work surveying

a railroad from St. John’s N.D. to Brandon Manitoba.

They

rejected a crossing straight south of Minto (where Highway#10 runs

today) as at that point the valley is both deep and wide. Instead they

selected a site a bit upstream where the southern lip of the valley,

although steep, brushed right up against the stream, while the gentle

slope on the north side could be crossed with a modest embankment. To

get there, the line bends westward as it approached the Souris and

follows the curve of the river.

The

elevator and station established on the south side of the river was

called Bunclody, a name already in use for a nearby school and Post

Office.

The

community had its beginning when George McGill and James Copeland

settled with their families along the banks of the Souris River in

1881,

A

school was built in 1884 and George McGill, the Secretary-Treasurer

was given the privilege of naming the school. He chose the name of the

district he left in Ireland.

The

first church services in the Bunclody district were held in 1883 in

the home of Mr. James Copeland and later moved to the school in 1886

and held there until the church was built in 1908.

Crossing

the river was a necessity, and there were three ferries in

operation in the 1880's. The Osborn Ferry near the settlement, the

McGill Ferry was three kilometres upstream and Shepherd's Ferry, not

far from where Highway #10 crosses river now.

In 1893

a pile bridge was built and in 1902 the river was very high and

all the bridges from Souris to Wawanesa were taken out with the ice

flow in the spring.

In 1903

the first span bridge was and that served until 1937.

That

was Bunclody in 1905, a community, but not a village. It was the

decision by the Great Northern Railway, a giant U.S. corporation, to

build a line into Canada that put Bunclody on the map.

A

Big

Project

The

river crossing made Bunclody the major construction site of the

whole project. Three work camps were quickly set up, one at the deep

ravine three kilometres south of the crossing, one at the town site on

the south side of the river where the station house was built, and one

on the north side of the river. Each camp had a steam shovel, modern

technology not available a mere 25 years earlier when the CPR crossed

Manitoba. Dinky engines were used to haul and dump cars as the grade

was built up. It was a major engineering project undertaken by one of

the largest America railroad.

The

ravines south of the river were crossed by building temporary

trestles and dumping fill to create a road-level earthen dam, complete

with huge pipes designed to let the runoff through. The pipes soon

broke and had to be replaced with concrete tunnels two metres square -

still quite visible today, although somewhat clogged with rubble. One

resident told me about boyhood adventures that included a dare to go

through the tunnel.

The

bridge over the Souris was 132 metres long and 26 metres high.

Timber for the trestles, including 30 metre long cedar pilings had to

be hauled from the CN Rail stop at Carroll, about eight kilometres away.

The

elevator and station, along with a bunkhouse for some of the many

full time employees required to maintain the line, were situated

halfway up the southern ridge of the valley, half a kilometer from the

bridge. The water tank was on the far side of the river slightly north

of the bridge, with pumps and pipes to draw river water for the steam

engines.

Crossing

the Souris at Bunclody

Crossing

the Souris at Bunclody

Preparing

the grade towards the crossing of the Souris near Bunclody.

Preparing

the grade towards the crossing of the Souris near Bunclody.

Today,

standing on the old rail line where it abruptly ends atop a

steep cliff at the river's edge, having followed it from that site

through a pasture as it curved towards the former crossing, one can

look northward across the river and see one of the few remaining

obvious signs of the old line. Directly below you, in the centre of the

river is a small gravel bar, once the base of the central bridge

support, and across the river where the valley wall slopes gently away

from the water's edge, is the high embankment built to carry the line

gently across the wide valley.

Bunclody

never became a very big village, but it did become a busy

place – for a while.

From

the day that first train came through on June of 1906, there were

two passenger trains per day, going south at 8 a.m. and north at 7

p.m., six days a week. The freight train ran every day, south on one

day, north the next, except Sunday.

The

abandoned rail bed and the foundation of the bridge were readily

visible from the air in 2001.

The worst spot was the Wilson Cut two kilometres north of

Heaslip, the

site of an adventure in March of 1923. A train with two engines and a

snowplow was stuck and snow drifted in half-way up the windows. In such

cases, neighboring farmers were often called upon to help out and the

presumably patient passengers relied on the kindness of strangers

so-to-speak. Supplies were brought from the Heaslip store and lunch was

served.

Spring

runoff also could be a problem when the pipes (culverts) under

ravine embankments couldn't handle the water.

But

other than snowfall, and a few problems with clogged culverts at

spring runoff, very few things interrupted the service. Doctors and

patients relied on it. It evolved from being a novelty to being a

necessity.

The End

of The Line

By late

20's it was apparent that big profits for the company would

never materialize. The line had been built into an area that was

already served by east-west lines. Unlike the original CPR lines, the

owners had been prevented from making large start-up profits from the

establishment of towns and the grants of land often associated with a

new line. With the defeat of Laurier in 1911, the hope of a reciprocity

agreement with the US, which would have increased north-south freight,

was effectively over. The population had reached its peak and the car

was establishing itself as the mode of choice for personal

transportation.

This

possibility of reciprocity had encouraged the expansion of the

Great Northern and some speculated that it would lead to a large

portion of the grain harvest being transported through the U.S.

Needless to say, there were many Canadians opposed to reciprocity for

that very reason. The Portage La Prairie Weekly noted that “The Great

Northern Railway…has no less than seventeen different lines operating

between Canada and the country over the border…: and could see that

much business would go that way. “ 1 That was a pretty good argument

against Reciprocity from a western point of view.

Another

force at play was the growth of the cooperative initiative that

became the Manitoba Pool Elevators.

"Part

of the problem … was that farmers were prepared to support the

Manitoba Pool, even at a financial cost to themselves." McCabe had

monopoly on the GN line, thus there were no Pool Elevators along its

route. At one time Pool was paying 53 per bushel while McCabe as much

as 75. By 1929 losses had mounted to $74000. In 1935 grain

tonnage on the line was only 16.5 % of what it had been in 1913. 2

At the

same time passenger service fell off. Although it was never

intended to be the primary source of income, it was helpful to the

bottom line. In 1906 travel by auto was slow and unreliable. But people

really liked the freedom the car gave them, and better roads along with

cheaper, more reliable vehicles developed rapidly. By 1922 a "highway"

existed from Brandon to Boissevain and on to the border. By 1927 rail

passenger numbers began to decline.

The

depression worsened the situation and only pressure from the

government kept it open until 1936 when the mail contract ended. It was

simply no longer a viable enterprise, if it ever was. The tracks torn

up in 1937 after there were no offer for the purchase of the line. The

company formally continued to exist until Dec. 12. 1963 to allow for

ongoing land transfers.

The

last train ran June 14, 1936. Brandon railway historian Lawrence

Stuckey remembered with apparent fondness the day when he and a friend

waved to the engineer for the last time. 3

So

ended a chapter in the region's transportation history. The line is

credited with ending the rural isolation felt by many Westman settlers

and offered them an important timesaving travel option. Daytime

shopping trips to Brandon were a treat, students at university could

get home for weekends. But the car and the improved road conditions

offered a new sense of freedom to rural residents, and the line, though

remembered fondly by old-timers, was just not needed any longer.

So in a

way the Bunclody story is the story of not one, but two false

starts.

Sources

1.

Portage La Prairie Weekly July 26, 1911

2.

Everitt p84

3.Bain

& Stuckey p14

Todd,

John, Jim Hill’s Canadian Railway, Canadian Rail No. 283, August

1975, Canadian Railroad Historical Association, Montreal

Everitt,

John, Kempthorne, Roberta, Scafer, Charles, Controlled

Aggression: James J. Hill and the Brandon, Saskatchewan and Hudson’s

Bay Railway, Brandon University, 1987,

Rose,

D.F., Bunclody Community, 1879-1970, Bunclody Community, Carroll

MB.,1970

Archival

Bunclody photos were taken by Gilford Copeland and provided by

Alan Rose.

Manitoba

Telegram June 5., 1906

The

Souris River at Bunclody

|