So as we approach

that hectic period when Brandon was created, we see that conventional

thinking in 1879 wouldn't have predicted that in less than two years

the new town would appear overnight, and within days this unanticipated

collection of hastily erected commercial buildings would become the

most important place on the prairies west of Winnipeg.

The summer of

1880 saw quite an upswing in activity in the neighbourhood of the

future city of Brandon and the Winnipeg newspapers did take an

increasing interest in the happenings in our area. For instance on

April 16, 1880 the Winnipeg Times reported that; "A ferry has been

established at the Grand Valley crossing of the Assiniboine River. This

will give people visiting the Souris country from the north shore

better travelling facilities. Another ferry is projected at Brandon

crossing 15 miles further down the river." (5) 16-April, 1880 -

Winnipeg Times

The article seems

to indicate that the importance of the Grand Valley location was that

it offered access to the regions to the south were settlements near the

mouth of the Souris, and in the Turtle Mountain area, were just

beginning. That is not to say Grand Valley wasn't a destination in and

of itself. The McVicars, who first appeared in 1878, had established a

river crossing, a steamboat landing and eventually some warehouse

buildings to facilitate its role as a river port. But that was about

it. The article also reminds us that although the name Brandon appears,

its use bears no relationship to the site of the current city. The

projected "Brandon crossing" ferry sight would in fact close to the

location of the former fur trade posts at Souris and near the already

established town of Millford. If the term was used in reference to a

community, that community would be the Brandon Hills settlement.

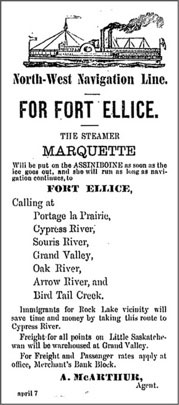

Stops

on the

steamboat route didn’t include Brandon.

Stops

on the

steamboat route didn’t include Brandon.

7-May,

1880 -

Winnipeg Times

The above ad

reminds us that in the pre-settlement days place names had flexible

meanings. A place didn't need to be a "town", in the sense that we know

it, to be on the map. Indeed in the sparsely settled land that we now

call home, towns and villages were of little consequence. There weren't

enough farms, therefore, enough commerce, to justify them. Portage la

Prairie was a town, indeed an important one. Cypress River, Souris

River, Oak River, Arrow River and Birdtail Creek were not towns but

landings named after streams entering the Assiniboine. (Cypress River,

Oak River and Arrow River would later come to identify towns, but in

each case many kilometres from the river landings.) In the case of

Grand Valley, although it later aspired to being a town, it was, as we

see, essentially a landing - a stop on a route.

Another

informative story, from The Winnipeg Times in May 17, tells us of a

party of sixty immigrants brought to Rapid City as part of an organized

colonization program. It reminds us the Rapid City was expected to be

the commercial centre of the region.

On January 6,

1881, The Winnipeg Times reprinted a Letter to the Editor from the

Montreal Witness about, "an educational institution recently

established in Rapid City." The letter outlines the reason for the

establishment of said institution: "allow young settlers (men) to

receive a good mental training" and to be "brought under the influence

of the gospel." The letter is notable for two reasons. Once again

we witness the pre-eminence of Rapid City as the place to be in western

Manitoba (technically still the Northwest Territories). As well, we are

witnessing the beginnings of the McKee Academy, which later moved to

Brandon, setting up shop on the upper level of the Fraser Block before

being incorporated into the Brandon College. All in all it tells us

quite a bit about Brandon's roots.

So in the winter

and early spring of 1881 we see only hints of the changes that were

taking place in terms of settlements, post offices and routes.

Hindsight allows us to see the occurrences in these few months as what

we might now term a paradigm shift in settlement patterns; all hinging

on the C.P.R. decision to follow a much more southerly route to the

Rockies, which would soon be followed by the choice of the exact

location of the necessary Assiniboine crossing.

By the end of

March 1881, something was in the air. Discussion was taking place, and

decisions would soon be made that would alter the future of settlement

and commerce in western Manitoba.

The month of

April, 1881, which was to become, in hindsight, such an important month

for the future city of Brandon, was quiet in the media. But the

news that did appear turned out to be quite important.

The Toronto Daily

Mail, (April 5, 1881) under the heading, "Manitoba Notes", datelined

April 5, has picked up the story that "General Rosser, chief engineer

of the Canadian Pacific railway, has returned from locating the second

hundred miles west, and has instructed the district engineer to direct

the main line some distance east of the terminus a hundred miles, so as

to run south-westerly toward the Assiniboine, and cross near the rapids

of that river."

The rapids are a

few kilometres downstream from today's Brandon. If you drive east on

Richmond Avenue as far you can, walk down to the riverbank and look

south, you will be looking at the very beginnings of those rapids. It

is clear from this article that the exact site of the future crossing

has not been chosen, but that article and the rumours that would

certainly have accompanied it, would have caught the interest of

settlers, or anyone with an interest in speculating in the region.

This would

confirm the worst fears of settlers along the Carleton Trail. The

railway that they felt was coming their way would bypass them. Their

loss would mean an opportunity for settlers and landowners along the

newly announced southern route.

Buried in the

third paragraph of an article in the Toronto Daily Mail (April 18)

(reprinted from the Winnipeg Times but based on "Cable news from

England") we learn that at a meeting of the shareholders of the

Canadian Pacific railway has announced that, "350 miles of railway west

of Winnipeg are expected to be in operation by the end of the present

year." and it later refers to "the crossing of the Assiniboine at Grand

Valley". We also learn that "General Rosser has just returned from a

reconnaissance of the proposed route for some distance west."

There was no

doubt that the immediate vicinity of our hometown was about to become a

more important place, but details remained sketchy, and the exact

location of the crossing was either not yet decided, or kept secret.

As recently as

February 11 of 1880 an ad by the CPR in the Winnipeg Times sought

tenders for the construction of a rail line line from, "near the

western boundary of Manitoba (at that time this was near Gladstone) to

a point on the west side of the valley of Bird Tail Creek.” It seemed a

done deal.

The announcement

that a rail line, in fact the main rail line, was now coming this way,

was a surprise. Some would say that was the whole point. The C.P.R. and

its operatives, General Rosser in particular it seems, stood to make

more money by opening up new towns rather than visiting established

ones. Whatever the motivation, the railway was coming and excitement

would follow.

May, 1881

One finds, from

early May, increased confirmation the railway would cross the

Assiniboine near Grand Valley.

How was the

decision made to locate the station, and thus the town site where

Brandon sits today? Why was it not located on the site of Grand Valley,

an established steamboat landing and ferry crossing with a post office,

store and a few other facilities? There are two theories. One is that

physical aspect of Grand Valley was not suitable. The river was

high that spring and the Brandon site offered a more secure location.

The other story is that Dougald McVicar, the owner of the Grand Valley

site held out for a higher price and Rosser, who intended to make a

profit himself on the creation of town sites, found a better deal

upstream.

The Grand

Valley

Incident

When rumours

began to circulate that the transcontinental railway, instead of

following the expected, more northerly route, might cross the

Assiniboine nearby, it began to appear that the little settlement at

Grand Valley might be destined for greater things.

Hindsight allows

us to see the occurrences in these few months as what we might now term

a paradigm shift in settlement patterns - all hinging on the CPR’s

decision to follow a much more southerly route to the Rockies.

The speculation

ended when Brandon was selected as a place for the crossing and the

all-important divisional point.

How did that

happen?

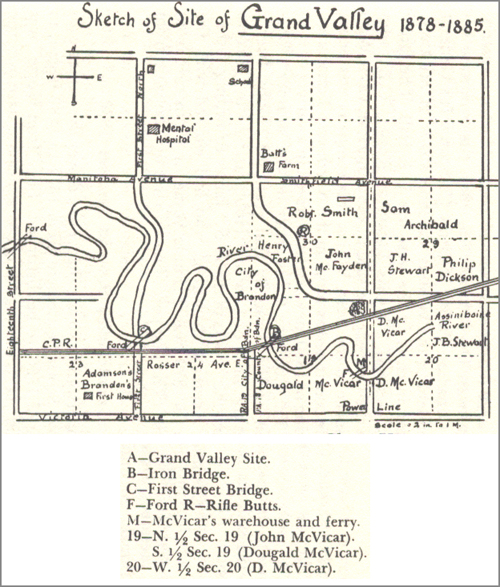

Grand Valley Map

- Kavanaugh, The Assiniboine Valley

General

Rosser

Enter Thomas

Lafayette Rosser, Chief Engineer of the CPR. Rosser was not your

typical railroad engineer. In fact, it is proper to refer to him as

General Rosser, an American no less, southerner even, and a

well-respected veteran of the American Civil War.

In fact he was

also a friend of the late Union General, George Armstrong Custer, his

former adversary, with whom he had worked in his previous position with

the U.S. Northern Pacific Railway. Custer’s ill-fated 7th Cavalry had

been assigned to protect the workers and he and Rosser had struck up a

friendship.

Now Rosser was

about to play a pivotal role in the settlement patterns of the Canadian

West.

In the spring of

1881 he crossed the Assiniboine River at a point about 200 kilometres

west of Winnipeg, bargained briefly with a Mr. Adamson and purchased

the town site of Brandon for little more than a song.

As with many

other deals struck in the creation of railway towns in the era,

potential profit for Mr. Rosser was a consideration. He’d just rejected

the site of Grand Valley, just a few kilometres downriver in a famous

confrontation with area pioneer John McVicar, who had his own notions

about profit.

James Secretan, a

CPR surveyor who worked with Rosser reported that Rosser indeed made a

$25000 offer for the Grand Valley site, and when McVicar countered with

a request for $50000, the General abruptly ended negotiations and moved

on upstream.

According to

Brandon pioneer Beecham Trotter’s account, the negotiations ended with

Rosser saying, “I’ll be damned if a town of any kind is ever built

here.” (1)

And it wasn’t.

On May 13, the

Winnipeg Times reports that, "Gen. Rosser is laying out the station

grounds and Mr. Vaughn is surveying the town plot adjoining the station

at Grand Valley, the Canadian Pacific Railway crossing of the

Assiniboine."

A few days later

(May 16) they report that the station will be on section 23, township

10, range 19, (the site of present day Brandon).

The name Brandon

has not yet been used, and on the very next day large ads appear under

headings such as, "The Grand Valley Crossing, site of the Great City of

the C.P.R and crossing of the Assiniboine River", and announcing that

said town" has been located by the Chief Engineer of the C.P.R. on

Section 23, Township 10, Range 19 West, On the south-west side of the

river". The ad continues in this vein making it clear that the C.P.R.

station will be on the aforementioned site and that .."Any other lots

advertised are from two to three miles distant from the station."

(Winnipeg Times, May 17, 1881)

This was a direct

response to the continued efforts to promote the original Grand Valley

location. But the issue was settled. The battle fought and won. Brandon

had a railway station and it would be the C.P.R. town. The

arrival of the CPR in the spring of 1881, transformed an empty stretch

of riverbank into a bustling city, almost overnight.

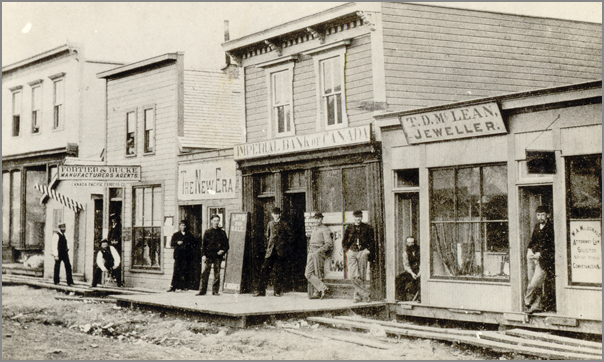

RosserAve1881

(Archives of Manitoba)

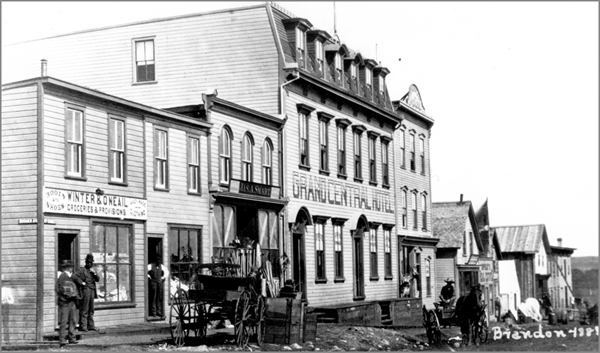

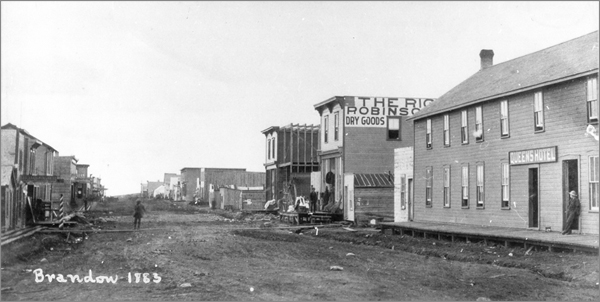

Sixth

Street

1883 (Archives of Manitoba)

In 1883

from

corner of Sixth and Rosser, looking north towards Pacific Avenue and

the Assiniboine River the three-storey Grand Central Hotel dominated

the streetscape.

By 1883 it had

progressed from a tent town of a few hundred souls and assorted

makeshift businesses to crowded streets lined with well-built stores

and hotel.

The

Grand Valley

site May, 2011. The village was near the centre of this photo - under

water as it was in June of 1881. Regardless of the details - the right

decision was made.

The

Grand Valley

site May, 2011. The village was near the centre of this photo - under

water as it was in June of 1881. Regardless of the details - the right

decision was made.

|