by A. B. McKillop

Department of History, Queen's University

MHS Transactions, Series 3, Number 30, 1973-74 Season

|

It is hard to know what to make of Mr. John Queen. Sometimes [he] is merely a Scottish haranguer and his speeches are moonshine and wind music ... At other times he stirs the heart by putting on what looks like a real battle for the improvement of life in Manitoba. "Under the Dome," Winnipeg Free Press (1935)

One of the most neglected elements within the spectrum of "political history" is municipal politics, and one of the greatest victims of this neglect is the municipal politician. Prime Ministers and cabinet ministers, Leaders of the Opposition and leaders of the back room receive their rewards from historians for having done their various duties in the national political arena. Forgotten for the most part are those school trustees, aldermen, and mayors who have traditionally held the responsibility of dealing on one hand with the consequences of national policies and on the other with the various exigencies of everyday municipal life. Theirs is the task of making government actually work at the level of politics that most obviously affects the people of any country. Some such municipal careers, it will be conceded, are of such a dubious calibre that perhaps they would best remain forgotten. Others, however, are not. One such career, once of national prominence but now largely remembered only by those who either were living in Winnipeg between the Wars or who have done so vicariously by reading the newspapers and other records of that city's history, is that of John Queen. The purpose of this paper is to recall, however briefly, some of the political concerns of that man, concentrating in particular on his first year as Mayor. It is to be hoped that the paper will also make obvious the need for further historical research upon the career of Mr. Queen and others like him in Canadian public life whose contributions to the nation, like that of Mr. Queen himself, are increasingly found only in the celluloid memories of the microfilm reel. [1]

It seems eminently fitting that during the year of Winnipeg's centenary the career of Mr. Queen should be recalled, for that career was to an extent, a mirror of much of the city's political life for almost half of the twentieth century. Queen was twenty-four years old when he arrived in Winnipeg from his native Scotland in 1906. He wore a handlebar moustache and he carried a cane. The day was Decoration Day. It was August, and it was hot. Sarah Bernhardt was playing to packed houses at the Old Auditorium rink in "Camille"; wheat was selling at a respectable 78¢ a bushel; and the spirit of financial and land speculation was in the air. "I can well remember getting on street cars and getting into conversation with the man alongside me," he later recalled. "The topic was invariably real estate, and the profits somebody made yesterday. Winnipeg was enjoying an orgy of speculation and get-rich-quick schemes." [2]

If Queen was at first enamoured with the broad and airy Winnipeg streets, the apparent friendliness of its people, and the general aura of prosperity exuded by the city, he was soon to have certain misgivings. His first concession to North America was his cane, which he left at home after receiving decidedly odd stares when he took his first Sunday "constitutional." His next modification in appearance was the gradual removal of his moustache: the Winnipeg winter saw to that. "It attracted too many icicles in the cold weather for comfort," he later told a reporter. But far more important than either of these was a change that was taking place in his attitude. Winnipeg was in several ways, even in 1906, a divided city: divided by a river and a set of railroad tracks, by ethnicity and by class. The contrast between the area of his Dorothy Street boarding-house and the stately homes south of the Assiniboine River which he observed as he bicycled around the city on Sundays confirmed this growing conviction that there existed in the city a number of inequities which impeded a true community spirit.

Once Queen had accustomed himself to the city, he became increasingly involved with its radical Labour groups (even though we are told that he had not been a socialist in his native Scotland [3]). Within two years he was a member of the Social Democratic Party of Canada in Winnipeg. The party had been formed in 1908 by a faction within the Socialist Party of Canada led by Jacob Penner, Saul Simkin, Matthew Popovitch, Fred Tiping, John Navizowsky and others who objected to the refusal of the S.P.C. to descend from the level of ideological mental gymnastics to that of party politics. Queen and Penner were to remain members of the Social Democratic Party for the next dozen years, a period which saw the boom of the early part of the century begin to slacken, and labour slowly become more willing to accept doctrinaire socialists within its ranks. [4]

An alliance of Queens and Penners, even in these early days, was an uneasy one. Penner was an orthodox Marxist; Queen a Socialist in the British tradition, more familiar with the writings of John Stuart Mill than those of Karl Marx. Indeed, one of his daughters has remarked that she was "raised" on Mill's On Liberty. [5] Queen's strong belief in certain of Mill's political principles sheds no little light on the brand of socialism exhibited by him in later years. "Was Mill a Socialist?" one prominent British historian has asked. "In his Autobiography he once called himself one, but it was a pragmatic and undoctrinaire socialism that he believed in." [6] The Socialism of John Queen was of this sort. Many of the statements Queen was to make in the 1920s and 1930s may be found almost verbatim in Mill's Autobiography. Others of his speeches, it is true, often sounded like Marx, but in the end Queen, like Mill before him, chose to view the end of social improvement as one that would (to quote from Mill's Autobiography) "... fit mankind by cultivation for a state of society combining the greatest personal freedom with that just distribution of the fruits of labour, which the present laws of property do not profess to aim at." [7] There is as much of Mill the liberal as of Mill the socialist in that passage, and - as will be seen - the quotation might well have served as the slogan for Queen's 1935 crusade as Mayor to change the basis of taxation in Winnipeg.

As one committed to the idea that social improvement should be brought about through existing political institutions, and also as a Britisher convinced that those institutions in their uncorrupted forms were capable of putting into effect such changes, Queen early took an active interest in the politics of Winnipeg and Manitoba. First as a member of Winnipeg City Council from 1916 to 1921, and later as a Member of the Legislative Assembly from 1920 to 1941, Queen consistently interjected a dissenting voice into political bodies which were for the most part heavily dominated by a pragmatic, utilitarian, and at times complacent frame of mind. [8] As an alderman under the Social Democratic banner in 1916 he insisted that an investigation be conducted that would call for a readjustment of income tax on a graduated basis, and that a commission be appointed by the provincial government to look into the matter of the rising cost of living. The next year he addressed himself to the shortage of coal in the city, to the low wages paid to soldiers, and to the need for the city to enter the area of handling and distributing milk. In 1918 he continued to voice his concern for the inadequacy of aid afforded to the dependents of soldiers. [9]

That Queen's career at the provincial level - along with others - was given its successful start because of his involvement in, and martyrdom after, the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 is a commonplace of Manitoba's provincial history. By 1919 he had been active in the Winnipeg Labour movement for more than a decade. He had contested and had won four civic elections; and his dissenting voice on City Council had made him a bete noire in certain political circles, editorial offices, and homes in the city. (This was especially the case during the turbulent years 1918 and 1919, when he urged, on and off Council, the recognition of collective bargaining and acceptance of the recently-formed union of the city's policemen. [10]) As advertising manager of the Western Labour News during the Strike, and as a leading member of the Strike Committee itself, he necessarily became a central and active figure in the Strike. He was jailed accordingly for his role in it. [11]

The events of the Strike and the trials of its leaders are so well known that they scarcely need to be recounted here. Queen ultimately served twelve months in Headingly Jail along with his co-"conspirators," but he was not actually imprisoned until 1920. In the meanwhile he sat during 1919 on the City Council where, among other things, he introduced a motion for adult suffrage in civic elections, moved that the June 9, 1919, City Council resolution (made during the Strike) that had required all city employees to pledge not to belong to labour unions be rescinded, and successfully moved that August 2nd of each year be declared a civic holiday. [12] During his term in jail he was re-elected as an alderman for the 1921 term and was also elected as a Labour member to the Provincial Legislative Assembly. [13]

Queen's career in the Provincial House was equally outspoken. Within a few months of assuming his seat beneath the "Great Dome" he had successfully moved (in alliance with William Ivens) that the Province "give to each person, upon his discharge from the Provincial Gaol, a sum of $10 in cash, and such clothing as is necessary for warmth and decency"; he was unsuccessful in moving that no public monies be spent on the forthcoming Reception for the Duke of Devonshire (then the Governor-General of Canada); and he was equally unsuccessful in his motion (again with Ivens) that "the capitalist system is the prime cause of international friction and war" and that the provincial government urge upon its federal counterpart a policy of rapid disarmament. A Queen motion for the recognition by provincial authorities of "peaceful picketing" was rejected by the House, with Premier Norris declaring that "no such thing as peaceful picketting [sic] could exist." [14]

The formation of the Bracken government in 1922 simply heightened Queen's discontent, for if the Norris ministry had not done enough to suit Queen it nevertheless had to its credit the fact that it was reform-oriented. [15] The Bracken administration was very different in tone. "Under the conditions prevailing in these Provinces," the Manitoba Free Press noted after Mr. Bracken's government had been formed, "knowledge of the technique of politics would be of no help to the Premier. Prof. Bracken is confronted with a business task, calling for powers of organization, foresight, acumen and sagacity - the qualities of the administrator and business man. These qualities, judged by his record to date, Mr. Bracken has." [16] The fact that, as W. L. Morton has suggested, the provincial election of 1922 "marked the culmination of the effort to get rid of politics" in Manitoba and to replace ideological and party divisions by an unobtrusive, efficient, and business-minded administration [17] gave the decidedly "political" Labour faction in the Legislature a strength of voice that far exceeded its strength in numbers. During the 1920s Queen and the other Labour members were vocal to the point of obstruction. Indeed, at several points during the 1920s and 1930s Queen led filibusters to obtain the redress of various social grievances.

The first of these took place over the matter of Sunday trains, which Queen wished to see allowed for the benefit of workers whose only day of recreation at the local beaches was the Sabbath. Such a proposal required changes in the Lord's Day Act, and therefore found opposition within the major Protestant denominations in the city, and hence in the Legislature itself. It took Queen several years before a statute allowing Sunday trains was passed and supported in the Manitoba Courts. The first Sunday train chugged to local beaches on June 10th, 1923. [18] A second major filibuster led by Queen also took place in 1923, over a Queen amendment that would have based representation in the provincial House upon population. The Queen amendment, which would have meant a shift of some of the province's seats from rural areas to the City of Winnipeg, was defeated. [19]

But the area of legislative activity in which Queen perhaps performed his most valuable services was his extremely effective work on the various Standing Committees of the Legislature - particularly on the Law Amendments Committee. By the end of his career, the Winnipeg Tribune scarcely a Queen supporter - was to admit that "although not a lawyer and never having had any legal training, few members of the Legislature had greater capacity for appraising effects of new legislation. He interpreted the law from the viewpoint of the humanitarian and in this respect, although always aggressive and insistent, he was much less radical than in the early years when he was an alderman ..." [20] The fact that on the eve of Queen's election to the mayoralty in 1934 the Winnipeg Free Press was to observe that "Mr. Queen wants a new order of society and Mr. Bracken offers him law amendments" - given the importance of his work on that very committee of the provincial legislature - perhaps affords no small insight into the nature of John Queen's socialism. [21]

When the first chilling winds of the Great Depression reached Manitoba in 1929, the career of John Queen had just passed its mid-point. His days as alderman had ended with the expiry of his 1921 term, but he was re-elected to the provincial legislature in 1922 and 1927. He was to be re-elected in the provincial elections of 1932 and 1936. Early in the 1920s he had helped to form the Independent Labour Party in Manitoba, just as his former confrere in the Social Democratic Party, Jacob Penner, had helped to found the Communist Party of Canada at about the same time. But as the Depression worsened, Queen's attention turned increasingly to the level of municipal politics, for it was there that the issues of most vital concern to him - those of the standards of social wellbeing - were fought. It also appeared to Queen that both the provincial and federal governments, in maintaining their policies of economic retrenchment in a time of severe human want, were guilty of gross negligence. In January, 1930, Queen, now I.L.P. leader in the Legislature, moved that the House express its regret that the federal Speech from the Throne made no mention whatsoever of the distress created by unemployment and (to quote the Canadian Annual Review) "gave no indication that the Government intended to do anything to solve the problem." Queen's proposal was soundly defeated. [22] Such federal inaction, coupled with provincial declarations that the problems of relief - although constitutionally a provincial responsibility - were impossible to solve at the moment because of inadequate sources of provincial revenue and insufficient aid from the federal authorities, appeared to Queen indicative of a seemingly unbreakable chain of dominion-provincial indifference. If the chain were to be broken anywhere, it would perhaps best be done at the municipal level.

That a stronger reform voice was needed on City Council was apparent to Queen for two reasons (in addition to the moral imperative of breaking the steel chain of indifference). The first was quite obvious: the depression got steadily worse. Whereas in 1930, 16,001 Manitobans were on relief, a year later that number had climbed to 56,410; and by 1933 it had increased to 74,195. At the same time, the basic monthly relief allowance for a family of four remained at $17.94. [23]

The second reason for the necessity for a more "radical" voice on Winnipeg's City Council was that in its general response to the Depression the dominant "Citizens'" faction on the council was in certain important respects simply the provincial Legislature writ small. In his history of the province, W. L. Morton writes that even in Manitoba and Winnipeg in the 1930s certain basic mental characteristics continued to dictate the tone and direction of social and political life. [24] As with the province itself, so with the city in which even then almost half of its inhabitants lived; and just as the various Bracken administrations during the 1920s and 1930s appealed to various ancestral virtues in order to justify and find support for their primary concern - the financial integrity and reputation of the City and the Province in the country and the world - so these appeals. and this priority, were carried to the level of municipal politics by men of like minds and similar backgrounds. "The lesson to be learned from the past," John Bracken stated in his 1934 Budget Speech, "is, that Governments, in the interest of the State, must resist, in even greater degree than before, all demands for new expenditures, no matter how attractive the results may appear ..." [25] And this conviction was reiterated for the first five years of the Depression by his counterpart at the municipal level, Mayor Ralph Webb. As Mr. Webb put the matter during his 1933 campaign against Queen: "[W]e have to live within our means. We will do everything we possibly can towards that end ... The secret of the success of the British people ... always has been that their word is good. British people came here and built this city. Their thrift was a virtue ... So let us keep up the good old British tradition, and be on the constructive side of the picture.... One of the constructive things we can do is to live within our means, ... and see that our city lives within its means." [26] Throughout the early 1930s this attitude remained the dominant one held by those who controlled Winnipeg's municipal political decisions.

Queen's increased involvement in municipal politics resulted in several attempts to win the mayoralty of the city. First against Winnipeg's perennial mayor, Ralph Webb, in 1932 and 1933, and finally against the veteran Chairman of the city's Finance Committee, John A. McKerchar, in 1934, Queen's campaigns were characterized first by the predictions of his opponents that dire consequences would follow for the city should its citizens elect a Socialist Mayor, and secondly by the more tangible (if no less ideological) question of the primary financial and social responsibilities of the city's administrators.

The origins of the first of these had been, of course, in the cathartic events of the General Strike, the prime political consequence of which had been that each of the city's politicians would henceforth be labeled as either a "Citizen" or a "Socialist." For Winnipeg civic political life after 1919 there were no ideological mixed labels. [27] This polarization was exacerbated as the social effects of the depression increased the revolutionary-sounding rhetoric that emanated from the Market Square, adjacent to the Council Chambers themselves. [28] It was not relieved as secret police reports on various radical labour groups and activities found their way onto the desks of the Mayor, the Premier, and the Attorney-General. (These reports even included the revelation that there existed a Communist plot to take over the City with the aid of several stolen Thompson machine guns.) [29]

The second basic issue centred on the question of whether economic retrenchment in a time of want was as sound a policy at the level of social ethics as some claimed it to be in the area of classical economics. From 1932 through 1934 Queen criticized all levels of government, attacked what he called "the financial interests" that were "demanding their pound of flesh" by living off the interest accrued on municipal bonds paid only through the curtailment of essential social services, and rebuked his mayoralty opponents in particular for being the municipal representatives of that twisted set of priorities. "I think by using the position of mayor of this city," he declared when launching his 1933 campaign, "I could start something of the nature of real assistance."

That prosperity is just returning is the keynote of Mayor Webb's drive, just as it is the keynote of his political chieftain, R.B. Bennett, ... and yet in July, 1933, there were 25,000 more people on relief in Manitoba than in July, 1932.

I would think Mayor Webb was warning you about me when he said this was no time to experiment ... This apparently is the time to stick by the ship so we can all go down together. [30]

To Mayor Webb, however, Queen's "empty phrases, cheap promises and threatened experiments with new theories" were nothing more than the rhetorical bombast of a man who could enjoy the combination of the maximum of righteous indignation with the minimum of political responsibility. Yet, in its own way, Webb's remedy was no less rhetorical. "The past few years," he declared in his reply to Queen's charges, "have been a great testing time for everybody, but we will be all the better for the sacrifices we have made and yet remained sound and loyal to the great fundamentals of British citizenship." [31] It was this appeal to the ancestral virtues of Anglo-Saxon Manitobans that made Ralph Webb Winnipeg's archetypal "Citizen." It was this set of priorities that allowed him, while chairman of the advisory committee on relief cases of the provincial Legislature, to declare: "We never pretended to give them all they can eat, only what we think is enough for them." [32] It was this amalgam of the rhetoric of the W.A.S.P. and the ethic of responsibility which caused the City Solicitor, Jules Preudhomme, to remark in later years that "What Webb could not employ in logic and eloquence, he made up in simple movement about the platform. Every hop on his artificial leg, secured a vote. [33] Ralph Humphreys Webb, British citizen and Great War Veteran, won the mayoralty election of 1933 by almost twice the margin over Queen than he had enjoyed the year before.

In the autumn of 1934, Mayor Webb announced that he would not run again for the mayoralty. His place as the Ctiizens' candidate was taken by a local grocer-turned-politician, John A. McKerchar, whose long career in municipal politics dated from 1897, and whose almost as long concern as Chairman of the city's Finance Committee for the sound financial reputation of the city had earned him the nickname "the Watchdog of the Treasury." [34] The 1934 mayoralty campaign dealt, like others before it, with the perennial problems of how to increase assistance to the unemployed and how to improve municipal services such as the sewerage system; but both of these ultimately depended upon the ability of the city to find additional sources of revenue in an economy the taxpayers of which, both individual and corporate, already bore almost impossibly heavy burdens. Because of this, the McKerchar-Queen campaign of 1934 hinged on whether or not the candidate accepted a report on civic taxation and assessment submitted to the City earlier that year.

In May, 1934, the Winnipeg City Council had appointed Thomas Bradshaw, President of the North American Life Assurance Company, and a former Toronto finance commissioner, to investigate "the fair and proper distribution of tax liability," assessment, and collection in the city. Such an enquiry had been urged back in 1932, when a number of prominent business and investment leaders (including C. C. Ferguson of the Great West Life Assurance Company, George Vale of Royal Trust, F. F. Carruthers of the Winnipeg Real Estate Board, C. E. Joslyn of The Hudson's Bay Company, J. W. Briggs of Oldfield, Kirby, and Gardner, Sir Redmond Roblin and Sir Charles Tupper) had written to Mayor Webb seeking ways of changing the rates of tax assessment and urging the reduction of civic expenditures in general. [35] Bradshaw's Report, brought down in July, recognized the difficulties faced by property owners in paying taxes, and recommended "a substantial reduction in real estate taxes [as] both desirable and imperative." [36] The reduction, however, was to apply only to "certain classes of property," mainly business, warehouse, trackage, and residential properties in the business or semi-business districts. [37] In order to make up the potential loss of revenue that such a tax reduction would represent, Bradshaw recommended the implementation of a 2% retail sales tax, a 10% tax on rents of rented homes and apartments, a 10% increase in water and hydro rates, the elimination of most tax exemptions, and a provincial tax rebate to the city. [38]

The Bradshaw issue, and the campaign itself, polarized the Winnipeg political community over nothing less than the question of the nature of social justice that was implicit in Bradshaw's conception of a "fair and proper" distribution of taxes. McKerchar made no pronouncements on the Bradshaw Report, preferring to run a quiet campaign that made no promises more extravagant - or specific - than to "give Winnipeg an efficient and progressive administration," to "maintain the present high financial standing of the city"; and to seek to broaden and redistribute the basis and burden of taxation in a more equitable fashion. [39] Queen condemned the Bradshaw recommendations outright and totally, claiming that the shift of the burden of taxation from corporations to people hurt most of all the very class of the population that such taxation was meant to aid. "The city must have revenue, of course," he said in opening his campaign. "The purpose of the other I.L.P. candidates and myself will be to see that in collecting the necessary revenue we do not depress the life of the people for it is already too low. We will try to get the revenue where it is, not from the poor people, but from the wealthy classes." [40] In the weeks that followed, Queen, aided by continued silence of his opponent, managed to equate the ideas on taxation of John McKerchar with those of Thomas Bradshaw; and he succeeded. In this he was no doubt assisted by the fact-which he delighted in pointing out-that despite his own opposition on Legislative committees to two applications by the City Council for an increase in water rates, the Legislature had approved it. And the "prime mover" for the increase, which saw water rates raised to the consumer by 50% (from 40¢ to 60¢) and to the wealthiest corporations in the dominion (the major railway companies) by only ½ of 1%, had been the Chairman of the Finance Committee, John McKerchar. [41]

The Home and Property Owners' Association launched a radio campaign in defence of the Bradshaw recommendations and attacking the I.L.P., but popular opposition to the proposals was on the whole so strong that ultimately McKerchar was forced into what amounted to a repudiation of them. [42] This simply allowed Queen to claim that he had now "converted" his opponent to his point of view. [43] Thus, a variety of factors turned Queen's 1934 campaign into his strongest yet: Webb's decision not to run; the silence of John McKerchar; the Bradshaw Report, an ideal election issue; and to these should be added the fact that the Workers' Unity League (Communist Party of Canada) decided not to run a mayoralty candidate in order to put their strongest man (Martin Joseph Forkin) forward in the aldermanic race. Queen therefore had a united Labour vote behind him, and the election results showed that the Bradshaw proposals had also given him not a few votes of Winnipeg's "Citizens." [44] On Friday, November 24, 1934, the voters of the city elected a Socialist Mayor.

The balance on City Council between nine Citizens' aldermen and nine Labour supporters gave the Mayor the deciding vote. In the next couple of days the Winnipeg Free Press made certain its readers were aware of this fact, with eight-column headlines: "LABOR WILL DOMINATE COUNCIL - COMPLETE RESULTS SHOW GROUP IN CONTROL FIRST TIME IN CITY'S HISTORY." [45]

John McKerchar's political career ended with his defeat. "We all know that Winnipeg is not making any headway," he was to declare a year later, after refusing to run again. "As a matter of fact, we know that Winnipeg has been going back ever since 1919." [46] With that he faded into the obscurity from whence he had come.

The inaugural meeting of Winnipeg City Council for 1935 was graced by the presence of no less than five ex-mayors. Ralph Webb, S. J. Farmer, R. D. Waugh, and Aldermen Davidson and McLean, along with the other civic councillors, heard John Queen give his maiden speech as Mayor of the City of Winnipeg. It was a speech which treated the questions that were then of paramount importance in Winnipeg and all over the world: unemployment, relief, squalid living conditions, and the never-ending search for their solutions. As former-Mayor Webb listened to the speech he must have contemplated Queen's coming year in office. He must have looked forward with anticipation to the point at which Mr. Queen, at last holding an office that included the exercise - and burden - of power, would realize the limitations of rigid ideological conviction in politics. The essence of the game was compromise, and compromise could only come about at the expense of ideology.

Queen's first, precedent-establishing year as Mayor of the City of Winnipeg, reflected the tensions inherent between (in Max Weber's terms) the "ethic of conscience" that is the touchstone of the ideological True Believer, and that had so often been reflected in Queen's actions and speeches in the past, and the more pragmatic and utilitarian "ethic of responsibility" that found almost perfect Manitoban representation in men such as John Bracken, Ralph Webb, and John McKerchar. [47] Fully indicative of the fact that yesterday's prime Socialist had become today's First Citizen, the first major legislative proposal of the Queen administration was legislation not directed toward "socialist" measures such as state ownership, but was instead derived from the need for redistribution and reorganization of existing governmental policies through the channels of existing governmental structures. Not unexpectedly, the reform proposal was based upon Queen's earlier rejection of the Bradshaw Report's recommendations.

Within two weeks of the first meeting of City Council in 1935, Queen was found in the Hudson's Bay Company dining room, outlining his own solution to the problem of civic taxation to the members of the very group which had provided the strongest opposition to him less than two months before - the Young Men's section of the Winnipeg Board of Trade. Once again, he flatly rejected Bradshaw's recommendations that water and electricity rates, as well as rents, be increased. He urged instead a drastic readjustment of the business tax, but the adjustment would be upward, not the reverse. Far from being taxed unjustly, Winnipeg's major businesses were in fact under-taxed. The total business tax for the entire city, he noted, was only $484,000. He went on:

In Toronto, one of the smaller department stores alone pays $83,797, or more than one-sixth of the total business tax collected in Winnipeg.

Two chain store organizations in Winnipeg, having two warehouses and offices, as well as 44% retail sales, paid, in 1934,

(missing page here)

13-39%; Dryden, 26.49%; Keewatin, 30.11%; WINNIPEG, 6.11%. [53]

In the provincial Legislature, Queen kept up his attack on the current limits on taxation, since it was there that the necessary amendments to the City Charter would have to be made. It was there, too, that opposition to Queen's tax reform proposals was strongest. An intensive campaign, led by Sanford Evans, John T. Haig, and the Attorney-General, William Major, was waged against Queen's proposed changes. This lobby was further aided by active support from the Winnipeg Board of Trade, the Home and Property Owners' Association, the Retail Merchants' Association, the Winnipeg Rate-Payers' Association, and large business and financial concerns located in the central business district of the city. Opposition intensified as the proposal entered the committee stages. Newspaper headlines echoed the concern: "PREDICT DIRE RESULTS IF PROPOSED BUSINESS TAX PLAN IS ADOPTED-ADVANCED BEFORE LAW AMENDMENTS COMMITTEE BY BATTERY OF LEGAL TALENT REPRESENTING DEPARTMENT STORES , CHAIN STORES, BANKS AND OIL COMPANIES." [54]

On City Council, the Finance Committee based its calculations for the 1935 budget upon the fact that the business tax proposals would pass, either in whole or in part, through the Law Amendments Committee of the Legislature. It therefore kept the mill rate at the same level as in 1934 (34½ mills), despite large increases in expenditure, especially in the area of relief, in the hope that the anticipated increase in business taxes would help to cover the deficit. [55] Meanwhile, the Law Amendments Committee of the Legislature, on which Queen naturally played an important and vocal part in defending his own measures, finally accepted in July a modified version of Queen's original plan. The compromise that was struck provided for a variation in assessment ranging from five to fifteen per cent. Even so amended, it meant a substantial increase in tax revenue for the city-from $484,562.60 in 1934 to an estimated $800,000 in 1935. [56] It also marked the final rejection of the Bradshaw proposals. [57]

There were, of course, many other issues faced and reforms sought by the Queen administration of 1935: the restoration of civic salaries (which had been reduced by 16 2/3% in 1932 and 1933); the need for an increase in relief allowances; the removal of tax exemptions of railroad property; the extension of the franchise to all British subjects over the age of twenty-one without regard to ownership of property. [58] Whatever stand Queen and the I.L.P. aldermen on Council adopted, they found themselves caught between the competing priorities of the ethic of responsibility and the ethic of conscience, for on City Council they were in fact not the party of the Left but of the Centre. From one extreme, the I.L.P. was attacked by the Civic Election Committee members on Council and by the business lobby, especially the Winnipeg Board of Trade, in the Legislature. In opposing the restoration of civic salaries, for example, this latter group had written to the Premier that in order for the city to "attain normal business conditions again, general business must survive, money must go back into enterprise ...

To that end [they continued], stabilized conditions are requisite, ordinary business principles must prevail and confidence must be restored. The difficulty after such catastrophes as we have just passed through, has always been to restore business confidence and it requires ... dominance of business principles in civic life. [59]

From the other extreme, Queen and his supporters on Council were constantly attacked by the two Communists on Council, Jacob Penner and Martin Joseph Forkin, for showing a willingness (that seemed to increase as the year progressed) to subordinate their social consciences to political opportunity in order to achieve what victories political circumstances permitted. The legislation that resulted during the year was thus the result of an intricate synthesis of impassioned pleas, responsible arguments, ideological rhetoric, and harsh statistics. In no individual was this mixture more in evidence than in John Queen.

For Mayor Queen, the middle years of the 1930s were a trying period, not only because he had accepted the responsibilities of office but also because he was one of the leaders of a political movement which was trying to gain the respect of an apprehensive and frightened national political community. He had been a member of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation from its inception. Because he had played a major role in the coalescence of western Labour groups in the late 1920s, he had been elected to the provisional national council of the C.C.F. at Regina in 1932. Throughout the decade he continued to lead the Manitoba section of the party. [60] But the party itself was changing. From the doctrinaire socialism of the Regina Manifesto and the socialist movement it represented, by the late 1930s the C.C.F. was to become a political party of social reform. By 1936 most references to socialism had been removed from C.C.F. propaganda; by 1938 C.C.F. policy placed greater emphasis on government planning than government ownership. [61]

Midway as it was between 1932 and 1938, the year 1935 perhaps caught the I.L.P./C.C.F. at the half-way point in the transition from movement to party. [62] Nowhere was this change better indicated than in the actions and policies of its leader. "It is hard to know what to make of Mr. John Queen," wrote a Free Press editorialist early in the year. "Sometimes [he] is merely a Scottish haranguer and his speeches are moonshine and wind music ... At other times he stirs the heart by putting on what looks like a real battle for the improvement of life in Manitoba. Yesterday afternoon was one of these times. Mr. Queen for once was not talking a murky brand socialism ... but firing at a target he could see and might hit." [63] The lessons learned by Queen as Mayor were having their effect. He was still active in his condemnation of the way previous administrations had curtailed essential services in order to balance their budgets, but gone were the cries for repudiation of the civic debt. [64]

In part, this shift was a response to the recognition that if the party were to become a permanent and important political organization in Manitoba and Canada it was necessary to fare well at the polls. The poor showing of the C.C.F. in Saskatchewan during 1933 and 1934, together with the consistently high level of support shown for Citizens' candidates for mayor in Winnipeg's north wards, suggested to Queen and other members of his party that although a sizeable proportion of the electorate was vaguely "socialistic" - in the sense of becoming increasingly aware of the need for certain forms of collective ownership and regulation in the economy - it was nevertheless ultimately committed to a way of life based upon capitalism. The "movement" in electoral politics is at a disadvantage. As the political scientist, Walter Young, has noted: it "may crusade to convert the infidel but it can hardly expect to do so by going to elect a government pledged to eradicate their way of life." [65]

The remainder of John Queen's career as Mayor, between 1936 and 1942, was a model expression of the political reformer in action; and as such, it revealed little of the "Socialist" Queen of earlier years. The best indication that this was to be the case occurred in that crucial year, 1935, when Queen himself nullified on a technicality, a Penner-inspired and T.L.P.-supported motion that proposed to increase the food allowance of those on relief in Winnipeg by ten percent. Queen's decision was undoubtedly based on the fact that due to the active opposition of W. R. Clubb, the Minister of Public Works - and behind him the equally opposed Winnipeg Home and Property Owners' Association - there was virtually no chance of the measure finding acceptance in the Legislature. [66]

In the end, whatever solutions existed to the day-to-day, mundane yet all-important problems faced by the municipal politician during the depression - unemployment, relief administration, public health, education, sources of revenue, housing, and the like-were to be found not in the various compromises struck in the City Council Chambers or even in the Standing Committee rooms; they were to be found instead in a reassessment of the constitutional arrangements on dominion-provincial relations that had been laid down nearly seventy-five years earlier by a group of Victorian gentlemen at Charlottetown and Quebec City, and embodied in Sections 91 and 92 of the British North America Act. The areas in which John Queen directed most of his energies as Mayor, after his initial campaign to readjust the tax base of the city, seem to indicate a recognition of this fact. Much of his time from 1936 on was spent in the provincial Legislature or in Ottawa making known, both to parliamentarians and to the press, the urgency of constitutional adjustments and provincial and federal legislation necessary for the coming into being of a full measure of social justice. This was especially the case with the problem of housing in Canada, and the Housing Programme that Queen single-handedly developed for Winnipeg became nationally-known and celebrated as a model of its kind. [67] Before his last term as Mayor ended in 1942, he had also held positions of leadership in such a national organization as the Canadian Federation of Mayors and Municipalities.

Queen's contribution to urban affairs, both at the national level and in his own city, did not go unnoticed in his own time. After commenting in 1940 upon the completion of Queen's twentieth year in the Manitoba Legislature and his sixth term as Mayor, the editor of the Municipal Review of Canada added: "But John Queen is something more than the official head of the great western community - he is a reformer with a realistic mind which he puts into action whenever he gets the opportunity." [68] In the same year the Municipal Review carried a definition of what constitutes a city: "A city," it noted, "is a community or group of people; it is not measured by buildings or boundary lines. The soul of a city is the reflection of the soul of a people. It is vision, moral stamina and backbone that makes a city, and these are human characteristics the intangible value that money cannot buy nor industry supply." [69] If there is a measure of truth in this claim, if vision, moral stamina and backbone do form the basis of civic life, it seems, in retrospect, distinctly appropriate that John Queen should have been the First Magistrate of one city at one moment in time.

1. Much of this paper is drawn from A. B. McKillop, "Citizen and Socialist: the Ethos of Political Winnipeg, 1919-1935", unpublished M.A. thesis, University of Manitoba (1970), especially Chapter Six: "'We Must Tax Where the Money Is"', pp. 192-235.

2. "John Queen", Winnipeg Free Press, November 17, 1934. The direct quotation from Queen in the next paragraph is also from this source.

3. "Interview with Gloria Queen-Hughes" (Winnipeg: July, 1970). Transcript in the Public Archives of Manitoba [P.A.M.1. The author was the interviewer.

4. See Martin Robin, Radical Labour in Canadian Politics (Kingston: Queen's University Industrial Relations Centre, 1968), pp. 118, 182n. See also: "Interviews Between Roland Penner and Jacob Penner" (Winnipeg: 1965). Copy in P.A.M.

5. Queen-Hughes interview, op. cit.

6. David Thomson, England in the Nineteenth Century (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1950), p. 50. See also Kenneth McNaught's perceptive comment on the nature of Queen's socialism in A Prophet in Politics (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1959), p. 135.

8. W. L. Morton, Manitoba: A History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1967), pp. 464-467.

9. Minutes of Council (City of Winnipeg: 1916, 1917): Sept. 18, 1916, pp. 488-89; Oct. 30, 1916, pp. 542-544; May 15, 1917, p. 285; May 28, 1917, pp. 306-307, 310; July 9, 1917, p. 393; Aug. 7, 1917, p. 459; Aug. 6, 1918, p. 387.

10. Ibid. (1918, 1919): Sept. 30, 1918, p. 502; May 26, 1919, pp. 395-396, passim. See also the Western Labour News, Dec. 27, 1918, for an indication of his involvement in radical Labour activities. He was not, however, present at the Western Labour Conference of March, 1919. See Robin, op. cit., p. 183.

11. Queen's involvement in the Strike is treated in the following: Richard Allen, The Social Passion (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971), p. 99; William Rodney, Soldiers of the Internationale (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1968), pp. 26n, 27; Robin, op. cit., p. 180n; McNaught, op. cit., pp. 119, 136; Norman Penner (ed.), Winnipeg: 1919 (Toronto: James Lewis & Samuel, 1973), passim.

12. Minutes of Council (1919, 1920): Sept. 29, 1919, p. 713; Nov. 10, 1919, pp. 842-843; March 15, 1920, p. 204.

13. McNaught, op. cit., pp. 136, 140; Robin, op. cit., pp. 206, 207n.

14. Canadian Annual Review (Toronto: Morang, 1921), pp. 760, 761, 766. Another Queen bill that would have made peaceful picketing lawful in strikes was rejected by the Manitoba Legislature in 1923. See C.A.R. (1923), p. 702.

15. Morton, op. cit., p. 373, passim.

16. Canadian Annual Review (1922), p. 777, The Free Press comment was in its July 22 issue.

18. See ibid., p. 415, in which Queen and the Sunday Trains issue is discussed. The course of Queen's efforts from 1921 is covered in the C.A.R. for 1921, p. 762, and for 1922, p. 768. See also Morris K. Mott, "'The Foreign Peril': Nativism in Winnipeg, 1916-1923," unpublished M.A. thesis, University of Manitoba (1970), pp. 99100, for a discussion of the Sunday Trains Question.

19. Canadian Annual Review, (1923), p. 698.

20. "John Queen Dies at 64", Winnipeg Tribune, July 15, 1946.

21. Winnipeg Free Press, February 14, 1934.

22. Canadian Annual Review (1920-30), p. 463.

23. Typescript of Budget Speech given by John Bracken, Friday, March 2, 1934 (Second Session, 19th Legislature), p. 7, in John Bracken Papers, 1934, P.A.M.; "Relief Increases are Provided for By City Council" unidentified clipping (UC), March 13, 1934 in Winnipeg Free Press Library clipping files, City Council Scrapbook, 1934, (CCS:1934), p. 36.

25. Typescript of Budget Speech ... , March 2, 1934, op. cit., p. 5. See also: "Bracken Lists Six Points in Recovery Plan," Winnipeg Tribune, Oct. 26, 1933, for an excellent summary by Bracken of his conception of the role of the State in the economy.

26. "Webb Says City's Credit Is Most Important Thing - 'Seems to Me Independent Labour Party Trying to Fool Our People', Says Mayor," Winnipeg Free Press, November 23, 1933.

27. See "Citizen and Socialist", op. cit., especially Chapter 2 ("'The Gulf Between"'), pp. 38-79 and passim.

28. Political extremism in Winnipeg, both in the City Council Chambers and on the Market Square, is examined in detail in A. B. McKillop, "A Communist in City Hall", Canadian Dimension, Vol. 10, no. 1 (April, 1974), pp. 41-50.

29. Ibid. p. 45. This matter (and political extremism in general) is documented fully in "Citizen and Socialist", Chapter 5 ("'Send Them Back to Russia, The Country of Their Dreams"'), pp. 165-191.

30. "Queen Launches His Battle for Chief Magistracy - Denounces Payment of Interest While 'Citizens Hungry' and 'Education Threatened'", Winnipeg Free Press, Nov. 14, 1933. See also: "John Queen Nominated as I.L.P. Candidate for Mayoralty ... ", in ibid., Oct. 30, 1933. and "I.L.P. Candidates Attack Alleged Policy of Drift," in ibid., Nov. 14, 1933. The I.L.P. and United Front claim that "social services [were] curtailed in the sacred name of economy" is supported by the following editorial: "Winnipeg's Civic Problems" Winnipeg Free Press, Nov. 16, 1933. Despite its policy of "economy" in government, Webb administrators from the 1920's had incurred increasing deficits: see City of Winnipeg, Submission to Royal Commission on Dominion-Provincial Relations (Winnipeg, 1937), p. 25. Copy in P.A.M.

31. "Webb Opens Fight with Attack on Cheap Promises", Winnipeg Free Press, November 17, 1933. See also: "Webb Criticizes Those Who Urge Debt Repudiation", Winnipeg Free Press, November 20, 1934.

32. "Webb and Flye are Targets for Queen's Attack", Winnipeg Free Press, November 23, 1933.

33. Jules Preudhomme, "Winnipeg as Seen by a City Solicitor", typescript in P.A.M., p. 175. Although organized in a highly disjointed fashion, this document provides unique perspectives on the public and private characters of those prominent in Winnipeg Civic life during the tenure of Preudhomme as City Solicitor (1920-42).

34. See "J. A. McKerchar," Winnipeg Free Press, November 17, 1934. One reason for the success of McKerchar's groceries firm was that early in McKerchar's civic career he was able to obtain the City's contract for the provision of food supplies for the city's welfare recipients. Charges were later made that some of those who had received foodstuffs from McKerchar's firm preferred starvation to eating "prunes ... unfit for human consumption, and ... butter [that] was rancid". Hearings were held in City Council and McKerchar was exonerated. See Preudhomme, op. cit., pp. 54-56.

35. Letter to His Worship, Mayor Webb, Alderman McKerchar, Alderman Simonite, Mr. H. C. Thompson (City Treasurer), and Mr. Jules Preudhomme (City Solicitor), April 29, 1932; in Province of Manitoba, Department of Municipal Affairs, "Winnipeg City" File. Legislative Buildings, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

36. City of Winnipeg, Report of Commission on Assessment, Taxation, Etc. (Winnipeg, 1934), p. 16. See also: "Winnipeg Tax System Reviewed in Report," Winnipeg Free Press, July 31, 1934.

37. Ibid. p. 12. W. Sanford Evans had presented, on behalf of the Property Owners' Committee, "very complete data in respect to a group of twenty-two representative business properties, eleven situated on Portage Avenue, eight on Main Street, and the others on adjoining streets". (p. 26)

39. "McKerchar, Opening His Fight for Mayor's Chair, Outlines His Platform", (UC), Nov. 15, 1934, Winnipeg Free Press Library Civic Election File [CEF], 1934. For more information on McKerchar's campaign see: "North End Citizens Urge McKerchar to Contest Mayoralty", (UC), September 22, 1934, CEF:1934; "Webb Announces That He Will Not Seek Re-election-Pleads for Acclamation for McKerchar, Whom He Pledges to Support", (UC), October 1, 1934, CEF:1934.

40. "John Queen Opens His Battle for Chief Magistracy" (UC), November 13, 1934, CEF:1934.

42. See, for example, "Radio Talk No. 5", typescript of a programme aired on November 19, 1934. Copy in Bracken Papers, 1934, P.A.M.

43. "Queen Promises to Be More Than Council Chairman ..." (UC), November 17, 1934, CEF:1934; "McKerchar Will Not Support New Tax Proposals," Winnipeg Free Press, Nov. 17, 1934; "Queen Declares He Has Converted Ald. McKerchar -I.L.P. Candidate Warns Against Last Day Bogeys and Scares", ibid., Nov. 20, 1934.

44. "Citizen and Socialist", op. cit., pp. 207-209 and Appendix B "City of Winnipeg Mayoralty Statistics By Polling Subdivisions, 1932-1935", pp. 246-249).

45. November 26, 27, 1934. For an apt summation of the campaign, see "The Mayoralty", (editorial), Winnipeg Tribune, Nov. 24, 1934.

46. "Friends Told McKerchar is Out of Race - Refuses to Contest Mayoralty; Attacks Communists and I.L.P.", Winnipeg Free Press.

47. "Politics as a Vocation", in Hans Gerth and C. Wright Mills (eds.), From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology (New York: Oxford University Press, 1958) p. 120, passim. For an excellent justification of the postulation and usage of "pure type" models see Giovani Sartori, "Politics, Ideology and Belief Systems", American Political Science Review, Vol. LXIII (June 1969), p. 405. The conflict between these two "ethics" within the context of Winnipeg between the Wars is captured in fictional form to near perfection in John Marlyn's novel, Under the Ribs of Death (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1964), particularly in the Schiller barbershop scene, pp. 127-128. The conflict there might well have between Jacob Penner and John McKerchar rather than Mr. Schiller and "Alex Hunter".

48. "Mayor Outlines His Policy to Increase Winnipeg's Revenues - Queen Would Change System of Business Tax to Provide Different Rates for Different Classes of Business - Will Try to End Exemptions Enjoyed by Provincial Government and Railways", (UC), Jan. 12, 1935, CCS: 1935, Vol. I, p. 12. See also: "Queen Reveals Scheme to Jump Tax on Big Business ... (UC), Jan. 12, 1935, CSS: 1935, Vol. I, p. 4.

49. "Mayor Outlines His Policy ...", op. cit., p. 13, See Appendix.

50. Statistics provided in a copy of an address by C.F. Rannard to the Legislative Tax Committee, March 28, 1935, as part of a brief to that Committee by the Retail Merchants' Association. In Bracken Papers, "Board of Trade" File, 1935, P.A.M. See Appendix.

51. "City Faced with Likely Deficit of $392,876. in 1935-Hope of Balanced Budget Virtually Abandoned Unless Business Tax Approved," (UC), March 9, 1935, CCS:1935, Vol.I, p. 62.

52. "Report Claims Business Taxes Less Than East," (n.d.), CSS:1935, Vol. I, p. 77.

54. Winnipeg Free Press, March 22, 1935.

55. "No Change in City's Tax Rate Recommended-Finance Committee Votes Same Mill Rate as Last Year...", (UC), April 1, 1935, CCS:1935, Vol. 1, p. 91.

56. Statistics provided in an Open Letter from the Board of Trade to all members July 31, 1935, in Bracken Papers, 1935. See also: "Business Tax Will Bring $800,000 to City Coffers", (UC), July 22, 1935, CCS:1935, Vol. I, p. 9, for a summary of a report on the matter by City Assessment Commissioner, L. F. Borrowman.

57. Mr. Bradshaw, however, continued to stress nationally the importance of maintaining the confidence of investors in municipal bond issues, and the importance of maintaining public credit in general, in a series of speeches and articles. See: T. Bradshaw, "The Maintenance of Public Credit" (Speech to the Annual Meeting of the Ontario Municipal Association), The Municipal Review of Canada, (Oct. 1934), pp. 23-28; "Serious Consequences of Municipal Defaults", (address to the Annual Meeting of the North American Life Assurance Co.), ibid., (May, 1935), pp. 30-32.

58. On the wage restoration issue, see: the letter from a committee of civic employees to the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council, Province of Manitoba (2 pp.), in Bracken Papers, 1934; "Aldermen Renew Talk of Restoring Part of Wage Cut Reductions", (UC), April 9, 1935, CCS:1935, Vol. 1, p. 95; Minutes of Council (1935), June 4, 1935, p. 293; "Committee to negotiate With Civic Employees-" (UC), June 5, 1935, CCS:1935, Vol. I, p. 129; "Boost in pay of Employees of City Endorsed by Committee", ibid. Vol. 1, p. 134. On the Relief issue, see: "Relief System Change Urged Before Council", ibid. Vol. I, p. 14; Minutes of Council (1935), April 22, 1935, p. 217; "Advisory Board Decides Against Relief Increase" (UC), May 31, 1935, CCS:1935, Vol. I, pp. 116-117; "Council Holds Schedules are Not Sufficient - Penner's Motion Carried by Aldermen by Vote of Nine to Eight ..." Winnipeg Tribune, June 5, 1935; "Food Relief in City Raised 10 Per Cent By Council's Action", Winnipeg Free Press, June 5, 1935; "Province Makes Threat to Reduce City Relief Aid", Winnipeg Free Press, June 11, 1935. On the other issues, see: "Rail Tax Measure Passes Council by Eight to Six Vote - Will Now Ask Legislature For Change in Railway Taxation Act and Authority to Remove Exemption on Companies' Properties", (UC), March 19, 1935, CCS:1935, Vol. I, p. 80; "Committee Gives Approval to Adult Suffrage", Winnipeg Free Press, February 23, 1935.

59. Memorandum submitted on behalf of the Winnipeg Board of Trade by the Civics Bureau, July 29, 1935 (from a resolution by the Board of Trade dated February 18, 1935), in Bracken Papers (1935), P.A.M.

60. For Queen's role in the formation and leadership of the I.L.P. and C.C.F. see Walter D. Young, The Anatomy of a Party: The National C.C.F. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969), pp. 21, 42; McNaught, op. cit., pp. 205, 287-88.

61. Seymour Martin Lipset, Agrarian Socialism (New York: Doubleday, 1968), pp. 162-164.

62. Both Lipset and Young stress this transition in the C.C.F. Lipset pp. 169-196. Young is explicit: "Movement into Party, 1933-40", op. cit., pp. 68-100.

63. "Under the Dome", March 2, 1934.

64. His continued indignation at policies of economic retrenchment is illustrated in his letter to Prime Minister Bennett, reproduced in the Winnipeg Tribune, March 2, 1935, especially paragraph two: "While it is true that the city of Winnipeg balanced its budget last year so far as current expenses were concerned, this was only done by making very substantial cuts in school expenditures, social welfare estimates, grants to hospitals, our budget for scavenging and street-cleaning service, and the moneys appropriated for the use of our library. In fact, by a general curtailment in all our essential services, which are now all being operated at a standard that is much too low." But later in the same letter his changed attitude toward the city's credit is revealed: "What the city council is fearful of is that, if this load [the burden of relief] is not taken off its shoulders, the result will be a default in payment of our bonded indebtedness".

66. "Food Relief in City Raised 10% .. ", op. cit., See also: "Clubb Offers to Review Food Schedule" (UC), June 18, 1935, CCS:1935, Vol. I, p. 133.

67. For Queen's national campaign for better Housing legislation and programmes see: "Mayor John Queen, Winnipeg", (speech to the Dominion Conference of Mayors, Ottawa, 1936), in the Municipal Review of Canada (April, 1936), p. 10; "We Must Have New Homes!" (Paper read before the Annual Convention of the Union of Canadian Municipalities, Vancouver, B.C., August 19, 1936), in ibid. (Oct. 1936), pp. 10-11; "Housing Problem", (speech at the Third Annual Conference of the Canadian Federation of Mayors and Municipalities, June 11-13, 1940) in ibid. (Sept. 1940), pp. 16-17 (Queen's favourable reaction to the Rowell-Sirois Report is also recorded at this conference, ibid., pp. 21-22); "Housing Problem is Presented to Government", ibid. (June, 1942), p. 15. On Queen's Winnipeg Housing plan, see: "Winnipeg Has Ambitious Housing Scheme", ibid. (Jan. 1935), p. 31; "Mayor John Queen Discusses Civic Problems", ibid. (Feb. 1936), p. 18. As an example of national reaction to the merits of the programme, the Editor of the Municipal Review of Canada may be cited: "When we were in Winnipeg a few months ago, we found the mayor busy putting the finishing touches to an excellent, and in many respects original, housing scheme which he hoped would soon be carried out in his own city ..." ("Civic Leaders Win Merited Acclaim", Dec. 1938, p. 19).

68. "Mayor John Queen of Winnipeg", ibid. (December, 1940), p. 4.

69. George H. Cless, Jr., quoted in ibid. (October, 1940), p. 2.

The inadequacy of the business tax in Winnipeg had not gone unnoticed in years past. In 1917, a Commission authorized by Winnipeg City Council to investigate municipal assessment and taxation observed that "Rental value [as the basis of the business tax assessment] is ... no adequate proof of income or earning power," and that in 1916 "only 6.3 per cent of the civic revenue was raised by the Business Tax." They concluded that the business tax then in existence (based upon the annual rental value of the premises) should be abandoned and suggested in its stead an "Income Tax" on businesses based on "ability to pay." The "Draft Income Tax Law" that was appended to their Report was heavily influenced by the commissioners' study of Wisconsin Income Tax laws. See City of Winnipeg, Report of the Board of Valuation and Revision on Systems of Assessment and Taxation (Winnipeg, 1917), pp. 28-42, 66-75.

These recommendations were, however, not acted upon. In 1958, H. Carl Goldenberg observed that "Prior to 1935 the [business] tax [in Winnipeg] was levied at a uniform rate on all classes of business . . ." according to the annual rental value. "Rental value" was established in Section 292 of the City Charter as follows: "292. (1) Annual rental value for the purposes of this Act, shall be deemed to include the cost of providing heat and other services necessary for comfortable use or occupancy, whether the same be provided by the occupant or owner. (2) In assessing annual rental value, the assessment commissioner shall take all factors into account so that as far as possible premises similar in size, suitability, advantage of location, and the like, shall be equally assessed. The intent and purpose of this section is that all persons subject to business tax shall be assessed at a fair rental value of the premises occupied or used, based in general upon rents being actually paid for similar premises." See City of Winnipeg, Report of the Commission on Municipal Taxation. H. Carl Goldenberg (Winnipeg, 1958), pp. 76-77, passim.

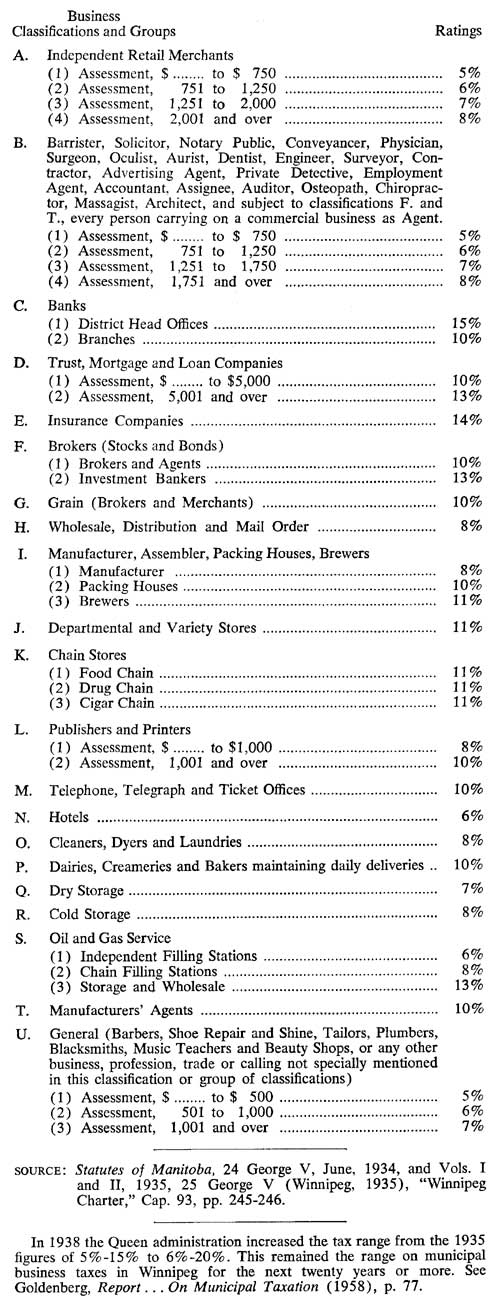

Queen's 1935 municipal tax reforms, as passed by the Provincial Legislature, came primarily in the form of an amendment to Section 282 of the Winnipeg Charter of 1918. As of April 6, 1935, the new municipal business tax structure was as follows:

5. Section 282 of the Act, as re-enacted by chapter 105 of the statutes of Manitoba, 1926, and as amended by chapter 115 of the statutes of Manitoba, 1927, is further amended by striking out all that portion down to and including the word "roll" in the fifth line thereof and substituting therefor the following:

282. For the purpose of levying a business tax in the city of Winnipeg, the assessment commissioner shall classify in accordance with the classifications hereinafter set forth the business of each person, firm, partnership, corporation or company carrying on business in any way in the city according to the principal trade, business, profession or calling carried on by such person, firm, partnership, corporation or company, and each person, firm, partnership, corporation or company shall pay to the city a business tax based on the annual rental value of the premises occupied, and at the rate per centum of the amount of business assessment for each such class thereof as shown on the business assessment roll; the said classes and the respective rates applicable thereto shall be as follows:

Page revised: 5 April 2022