by Tom Mitchell

Brandon, Manitoba

|

All history was a palimpsest, scraped clean and re-inscribed exactly as often as was necessary.

George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four

Place is a problematic concept with a complicated genealogy. Since the 1960s, cultural geographers have drawn attention to how the character, meaning, and significance of a place are products of human interaction with a physical site. From the 1980s, structurally oriented geographers have placed context and interaction at the centre of their accounts of how broad historical forces shape places and are in turn acted upon by the places they create. [1] In these accounts, places are necessarily transitory in nature: a place is always in a state of becoming or unbecoming. As philosopher Edward Casey has observed “place itself is no fixed thing: it has no steadfast essence.” [2] Places are a product of society and culture, but, as J. E. Malpas has noticed, nature’s work of shaping a particular physical environment is often the prerequisite for subsequent human activity associated with the creation of a place. [3]

Groups of Métis HBC trip men from Fort Garry crossed the Assiniboine River above the Grand Rapids on their way to Fort Carlton and farther points north and west.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Transportation - Red River Carts 26-46, P1230 / N133

My interest is in a place on the Lower Assiniboine River. In the almost complete absence of any living memory of this place the Grand Rapids of the Assiniboine what follows is drawn from geological and geographical accounts of the origins of the Assiniboine delta on the eastern edge of Brandon, and an excavation of the 18th- and 19th-century published and unpublished narratives touching on the Rapids. [4] In these sources, the Grand Rapids locale emerges as a prominentplace in Indigenous, Metis and fur trade geographies only to be transformed into an obscure anonymous space in the post-settlement era. [5]

My purpose is to mediate a dialogue on the past, present and future of the site, to reinvest the Grand Rapids locale with history and meaning, and to lay a foundation for its restoration as a place on the southeastern prairies. Historical research and public history are projects of recovery and creation. The mediation of contemporary public history publications, documentaries focussed on the landscape can foster the re-creation of places and give historical meaning to sites now defined mostly by municipal boundaries or various survey systems. As Charles Tilley has observed “... when a story becomes sedimented into the landscape, the story and the place dialectically help to construct and reproduce each other. Places help to recall stories that are associated with them, and places exist (as named locales) by virtue of their employment in a narrative.” [6] Names and historical narratives are instruments of cultural, social, and political power. [7] It follows that the production of place and historical memory is a contested dialogical project. [8]

The geophysical origins of the Rapids locale are important to any account of the site as a place. The physical attributes of the Rapids locale date from the end of the last ice age. In a two-hundred-year span, 11,200 BP to 11,000 BP, the abrupt and catastrophic drainage of glacial Lake Assiniboine left in its wake the Assiniboine Valley and the rocky, sandy terrain on the eastern edge of Brandon where the valley ends. Here the rocky, gravelly terrain at the apex of the Assiniboine delta on the western shore of Lake Agassiz furnished the structural foundation for the Rapids locale as a place on the eastern prairies. [9] The Assiniboine delta stretched west to present-day Portage contributing to the formation of the Agassiz steppe of 18,130 square kilometres (7,000 square miles) of prairie stretching across what is now southern Manitoba. Here, grasslands rooted in the rich soil of the former glacial lake attracted roaming herds of bison. [10]

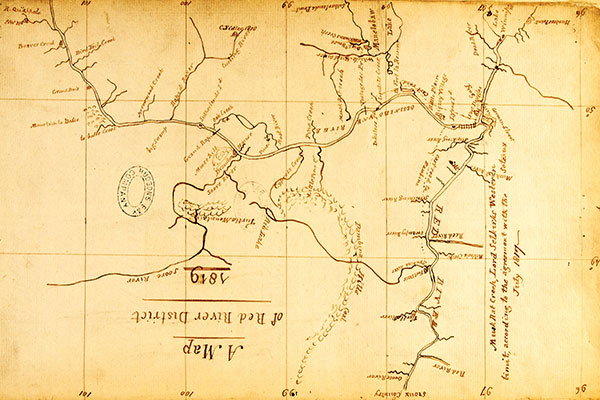

Peter Fidler’s map of southern Manitoba in 1819, reproduced here upside down so north is upward, shows noteworthy features along the Assiniboine River running left to right. Among them are the HBC’s Brandon House #2 fur-trading post (established on the south side of the river in 1811) about four miles above the river’s confluence with the Souris River (labelled “Soore River”) and the “Grand Rapid,” eight miles below the entry of Oak Creek (known today as Willow Creek). It is the first cartographic reference to the rapids.

Source: Peter Fidler, “A Map of Red River District 1819,” Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Archives of Manitoba, B.22/e/1

The Grand Rapids entered history when the fur trade on the Assiniboine came of age in the 1790s and posts of competing traders appeared above the junction of the Souris and Assiniboine. European traders were drawn to the area to trade with Assiniboine, Cree and Ojibwa who had made the parklands and steppe of southern Manitoba their homeland. The region also became the homeland of the Metis. Here, episodes of metissage the creation of cultural spaces between Indian and European societies opened opportunities for Metis ethnogenesis and the creation of Metis geographies. [11]

In the earliest documentary narratives of the Assiniboine River, a boulder-strewn section of the apex of the Assiniboine delta entered history as a place. John McDonnell, a North West Company wintering partner, on his way to the Qu’Appelle River, bequeathed the first written account of the Rapids locale. He introduced the Rapids to history as the Barrire as he paddled upward from the mouth of the Souris:

But to return to the Assiniboine River; it is very shallow and full of rapids for a day and a half’s voyage for the canoes to the Barrire, about five leagues over land from the posts at River la Souris, but after that, they go on well till they come to the sand banks beyond Mountain La Bosse. [12]

This Barrire was significant as a place as it obstructed canoe traffic on the Assiniboine. [13] McDonnell goes on to locate the Barrire a league an hour’s walk below the site at the terminus of the Assiniboine valley where Brandon now rests:

Near a league above the Barrire, on each side of the River, begins a ridge of hills about the distance of a mile; the summit of these ridges is only level with the rest of the plain country above, forming a deep vale between them, at the bottom of which runs the Assiniboine River, which keeps a continual winding from one side to the other of the hills called by the French, Grandes Cotes. [14]

McDonnell’s reliance on geographical references of Metis origin discloses the prior existence of an informal Metis geography of the Rapids locale. Throughout the nineteenth century, travellers in the prairie west acknowledged their reliance on Metis guides and trails. [15]

A second documentary narrative account of the Rapids locale appeared in Peter Fidler’s May 1808 journal of a trip down the Assiniboine. An HBC mapmaker, Fidler also refers to the Rapids as the barrier:

Sunday got underway at 4.57 and at 7:30 passed Oak Creek on NS, which comes out of a swamp all oaks hereabout low banks since Rapid River on both sides a large island just above Oak creek Saw the Moose head hill on SS pretty crooked, strong current with grassy sides and low willow banks came to a shoal rapid called the barrier, best water on NS 9:43 bottom of the rapid from top to bottom near 2 miles an island at bottom and shoal two other rapids in the middle, but the bottom the worst. A bare barren rather stony banks 2 miles below Oak creek and no woods. [16]

Fidler’s references to the Rapid River (the Little Saskatchewan), Oak Creek (Willow Creek), and the Moose Head Hills( the Brandon Hills), make the Rapids locale seem foreign, but his detailed sketch of the site remains accurate more than 200 years after it was written.

Fidler produced the first map in which the Rapids appear. In Red River and Its Communications, 1808, the Rapids site is presented simultaneously as the barrier and the rapids. [17] In 1819, on a map titled Manitoba District, Fidler presented the barrier/rapids as the Grand Rapids. [18] Fidler’s reference to Grand Rapids was not original. The phrase appeared in the post journals of the HBC’s Brandon House as early as 1795. [19] On 23 April 1795, Brandon House Postmaster Robert Goodwin reported that he had been visited by traders Cadott, Beaubien, and Rocheblave coming down the river after spending the winter trading at the Grand Rapids. These were the South mennMontreal-based traders who came to the Assiniboine from the south via the drainage basin of the Mississippi. One historian has called them the last coureurs de bois. [20]

Like Fidler’s journal reference to the Rapid River and the Moose Head Hills, the toponym Grand Rapids was almost certainly a rendition in English of the Indigenous term for Grand Rapids. [21] On the Saskatchewan River, the toponym Grand Rapids was derived from a Cree account of the rapids as Misipawistik or “rushing rapids.” One translation of the Ojibwa word mishi-Baawitigong is “little grand rapids.” A shorter version, Baawitigong, may be translated as “rapids” or as the Indigenous place name for Brandon. [22] Ojibwa elders in the Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation near Elphinstone Manitoba “still refer to Brandon as Baawitigoong, and understanding the origin coming from the Rapids.” [23]

The presentations by McDonnell and Fidler of the Rapids locale in textual and cartographic accounts inscribed a European spatial framework and toponyms on an existing Indigenous cultural landscape and brought into wider view the Rapids as a place on the eastern prairies. Throughout most of the 19th century, cartographers would follow their lead and inscribe the Rapids on maps of the eastern prairies. [24]

The South Traders had good reason to locate their trading establishment at the Grand Rapids. As North West Company trader William Mackay noted, it was located at “the Neck of land between them [Grand Rapids] and the West River [Souris River] where all ye Inds from this place are gone hunting, and where they get their best Trade in the red River.” [25] A detailed account of the Indigenous geography of the Rapids locale is beyond the scope of this paper. It is, however, evident that the Rapids locale was at the centre of an Indigenous cultural landscape of trails, gathering areas, spiritual centres and meeting sites on the eastern prairies. [26] In 1791, Donald Mackay, intent on establishing an HBC post of the Assiniboine, furnished the Company with a map on which, next to a representation of the Moosehead (now the Brandon Hills) Hills, Mackay explained that “here great numbers of Indians resort about 300 tents have been seen at once.” [27] Later, Brandon House postmasters would report that Cree and Assiniboine would go to the Moosehead to conjure. [28]

Mackay did not mention that a natural crossing existed above the Grand Rapids to facilitate travel north and south across the Assiniboine. That was left to Peter Fidler, who, as postmaster at Brandon House in 1818, described hundreds of Assiniboine people using the crossing after some time on the north side of the river secure from attacks by their sometimes enemies, the Mandan:

About 130 tents of Stone Indians crossing over the River the N to the S side where they have been since the melting of the snow out of the way of the Mandans [of whom]. They are continually in dread of nearly every spring .They are very troublesome to us for tobacco [and] ... our People at the Rapids was obliged to divide amongst them nearly 500 Lbs Pemmican. [29]

The crossing was above the Rapids, closer to the gravelly apex of the Assiniboine delta where low banks level with the surrounding prairie and gravely access and regress from the river offered the most natural crossing on the Assiniboine from its headwaters in central Saskatchewan to its mouth at the Forks. [30] The crossing gave the Rapids locale a particular salience for travellers of all kinds on the eastern prairies in an era of remarkable mobility when both Indigenous and Metis inhabitants of the eastern prairies “lived and thrived at the intersection of mobility and fixedness.” [31] For their part, Metis relying on the travel routes of their Indigenous forebears, pioneered several trunk trails that employed the crossing above the Rapids for passage across the Assiniboine. These trunk trails stretching west to the Rockies, southwest to the Missouri, and northwest to Fort Pelly and Edmonton made the Rapids locale a vital crossroads on the eastern prairies.

The role of the Rapids Crossing in the celebrated Metis buffalo hunt illuminates the importance of the Rapids locale as a crossroads. In 1821, the HBC swallowed its rival the North West Company. Many Metis the backbone of the fur trade had to find new work. They reinvented themselves as bison hunters and found work competing with their Indigenous cousins to supply the fur trade with country provisions. The historic Metis buffalo hunt was born. By 1840, the summer buffalo hunt from Red River involved 1200 carts and 1600 people. [32] In 1846, the hunters were organized into two brigades: one centred at Pembina and another on the White Horse Plains an area stretching west from St. Francois Xavier west towards Portage.

In his Report of 1860, Henry Youle Hind provided a narrative account and map of the route taken by the White Horse Plains brigade to the buffalo plains. The route led from the White Horse Plains to the crossing above the Rapids and southwest passed the Moose Head Hills to the killing fields of the Souris Plains and south to the Turtle Mountains. Hind explained that the White Horse Plain “goes by the Assiniboine River to the Rapids Crossing, and then proceed in a south-westerly direction.” In 1849, a brigade including 603 carts, 700 Metis, and 200 Indians took the Rapids Crossing to the buffalo plains. [33]

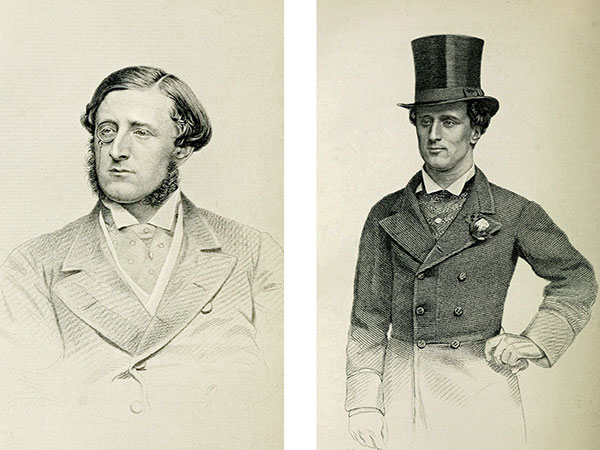

Metis guides familiar with this route led big game hunters to the crossing above the Rapids. In June 1861, 48-year-old Arctic explorer Dr. John Rae accompanied by 21-year-old Henry (later Viscount) Chaplin, and 20-year-old Sir Frederick Johnstone, with three Red River carts, and two wagons took the Rapids Crossing to the buffalo plains. The water in the river was high and the current strong; so, guided by their veteran Metis guide James McKay, the party made rafts of wagon wheels and oilcloth to ferry across the river while the horses swam. The operation took six hours. Once across the river, Rae took geographic coordinates of his location. The coordinates place him on the west side of the Assiniboine in the extreme southwest corner of Brandon. [34]

The Rapids Crossing to the buffalo killing fields became the stuff of historical legend. In 1880, CPR Engineer Marcus Smith, on the lookout for a crossing for the CPR, could not avoid a reference to the historic buffalo hunt in his account of the Grand Rapids:

From the mouth of the Souris River upwards the Assiniboine has risen nearly to the level of the plateau; its banks are low, and fine stretches of prairie are seen on each side. At the Grand Rapids, about 12 miles in a direct line above the mouth of the Souris, the banks are about 6 to 10 feet high and the valley has almost disappeared, only a gentle rise from the river to the prairie level is visible to the eye. Above the rapids the great trail to the hunting grounds of the south-west crosses the Assiniboine. [35]

From the 1840s, a growing commerce in buffalo robes with American trading posts in the Dakota Territory led some White Horse Plains Metis to specialize as traders. These traders pioneered the Traders’ Road across the prairies to Wood Mountain, the Cypress Hills and on to the Belly River in the foothills of the Rockies. On Sandford Fleming’s 1877 Map of the Country to be Traversed by theCanadian Pacific Railway the crossing above the Rapids is presented as the gateway to the prairies on the Traders’ Road. [36] White Horse Plains traders took the Traders’ Road west to trade sugar, flour, tobacco, alcohol and ammunition for buffalo robes, meat and furs collected by Metis and Indigenous hunters. At Wood Mountain, Metis traders did business with Dakota Chief Sitting Bull and his 5,000 followers who in 1876 crossed the medicine line seeking refuge after Custer’s catastrophe. [37] In his 1880 report, North-West Mounted Police Inspector Sam Steele complained that he could not prevent the smuggling of liquor into the Territory by those “crossing at the rapids, a point on the Assiniboine river, and take the south trail for the west.” Was he referring to Metis traders? [38]

Young and wealthy English adventurers Henry Chaplin (1840–1923, left) and Frederick Johnstone (1841–1913, right), accompanied by Arctic explorer John Rae and Métis guide James McKay with three Red River carts and two wagons, took the Assiniboine Rapids crossing to the buffalo plains in June 1861.

Both men would later hold seats in the British House of Commons.

Source: Bailey’s Monthly Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, Vol 10, No. 70, September 1865, 215-217 and November 1865, 323-24.c Hathi Trust Digital Library, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/ Record/010308010.

In an unpublished memoir, Lillian McVicar, daughter of Dougald McVicar, co-founder of Grand Valley in the late 1870s, left a poignant recollection of the Metis traders at the Rapids Crossing. Her father had to travel with ponies to Portage la Prairie for provisions,

except the pemmican and jerk meat, both buffalo meat, which he could get from the [Metis and Aboriginial] traders who went through the valley about once a year on their way to Winnipeg in their little Red River carts creaking along drawn by either an ox or a Shaginappi poney. These carts were usually heavily loaded with wigwams, bundles, children, and their own beaded handiwork, articles of all kind, that they offered for sale. These carts, about two hundred of them in the procession, was a very interesting sight and my father use to say it was very musical but lacked harmony. [39]

Brandon original Beecham Trotter recalled that the Traders’ Road was sometimes referred to as the Great Trading Route. [40] Trotter had arrived in the west a construction worker on the Canadian Pacific Railway telegraph line. His knowledge of the Traders’ Road was an artifact of his arrival in the west just as the curtains were closing on the era of free-ranging mobility. By 1927, the nature and extent of Trotter’s “Great Trading Route” would have been a mystery to most of his readers.

Metis also pioneered a trail across the Rapids to the northwest that became an important artery of commerce for the HBC. In 1831, Fort Ellice was establishednear the mouth of the Qu’Appelle to replace Brandon House as the principal HBC trading centre on the eastern prairies. In an era of increasing use of wheeled transportation, Fort Ellice became a destination point on this trunk trail the Fort Ellice Trail from Fort Garry in the east to Fort Ellice and west on to forts Carlton and Edmonton or north to Fort Pelly. [41] There were two branches of the Fort Ellice Trail: the north branch east of the Assiniboine that crossed to the west side of the river near the mouth of the Qu’Appelle, and the south branch that employed the Rapids Crossing.

The northern crossings there were at least two locations featured a steep and difficult descent into the muddy floor of the Assiniboine valley and an equally difficult ascent, especially in wet weather, to the plains above where Fort Ellice was located. H. Warre’s account, composed in 1845, of Milton’s Crossing noted:

At a distance of 10 miles or more we had a beautiful view of the Fort Ellice situated on the high point on the opposite bank of the Assiniboine River, across which we passed our baggage etc. in a small badly built boat, making the horses swim; the river was very rapid and the passage occupied 3 or 4 hours. [42]

W. B. Cheadle crossed the Assiniboine approximately one mile north of the point of Warre’s crossing in 1862.

On arriving at the river we descried a scow moored on the opposite side ... it proved full of water. Messiter got in with his horses; aground; pushed off; immediately sinks at one end and goes to the bottom ... Decided to try where the men had waded across ... Messiter first with his 2 got into deep mud ... Milton and I taking warning crept along water’s edge, plunging into a few deep holes, and at last scrambled up perpendicular bank and got on the track again ... [43]

The terrain associated with the southern crossing gravelly, sandy and level provided ideal crossing conditions. In 1880, Marcus Smith noted that at the Rapids Crossing the river was near “the level of the plateau; its banks are low, and fine stretches of prairie are seen on each side. ...the valley has almost disappeared, only a gentle rise from the river to the prairie level is visible to the eye.” [44] Gravelly approaches, gentle descents and ascents to and from the river, and usually low water in a gravelly riverbed made the site ideal for cart traffic.

Cartographic records and personal first-hand accounts of the crossing on the south branch to Fort Ellice provide an imaginative space to rekindle historical memory of the crossing and the trail. [45] In his memoir, The Company of Adventurers about life as a mid-19th-century HBC employee Isaac Cowie recalled the Rapids Crossing in an adventure he had making his way down the Assiniboine River from Fort Ellice in 1871 transporting a load of buffalo robes:

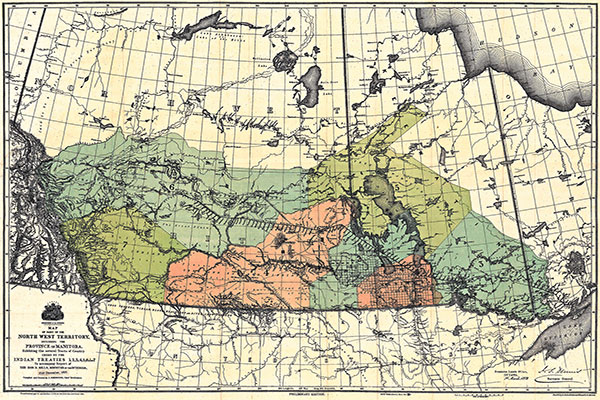

A map of western Canada, circa 1877, shows the areas of the numbered treaties. A point defining the western-most boundary of Treaty 1, encompassing much of modern-day Manitoba, is the crossing above the Grand Rapids of the Assiniboine. The crossing had been used for generations so it was a well-known landmark for residents of the eastern prairies.

Source: Johnston, J. Map of Part of the North West Territory Including the Province of Manitoba Exhibiting the several Tracts of Country Ceded by the Indian Treaties 1,2,3,4,5,6 and 7. To accompany report of the Honorable Minister of the Interior dated 30th June, 1877 [map]. 1:2,217,600. [Ottawa]: Canada Dept. of the Interior Dominion Lands Branch, 1875.

By the time we reached the Rapids near which the river was forded by carts (near Brandon), we had nothing to eat; but we saw the fresh tracks of a train of carts which had crossed going north. Hoping to get some food from them [we] ... followed the trail. Along the way we saw the decomposing bodies of three Sioux who had very shortly before been killed and scalped by a party of Red Lake Ojibways ...The carts turned out to be laden with freight for the Company at Carlton, and the Metis who were taking it were only too pleased to get rid of part of their heavy loads by letting us have four bags of flour... [46]

As the settlement era dawned in the 1870s, the Fort Ellice Trail via the Rapids Crossing took on growing importance. In 1878, the Canadian government published a table - Trail Distances from Portage la Prairie to Fort Ellice, via the Rapids of the Assiniboine River - based on distances measured in 1873 by Robert Bell of the Geological Survey employing an odometer attached to a cartwheel. [47] It was 188.7 miles from the HBC store in Portage to Fort Ellice via the Rapids Crossing; 109 miles from the Rapids Crossing to Fort Ellice.

Like John Rae’s coordinates of latitude and longitude, the table provides data to fix the location of the Crossing. From the Crossing, it was 1.2 miles “to a creek.” On the west side of the Assiniboine, the creek has taken on the appearance of a marsh. Here, on its north fringe, 1.2 miles from the river, is the historic terrain of the south branch of the Fort Ellice Trail. Cart trains of HBC trip men, big game hunters, and settlers passed this point heading west or northwest on the eastern prairies. The south branch to Fort Ellice led west to Boss Hill Creek near Oak Lake then northwest to Fort Ellice and beyond.

From the late 1700s, the Rapids locale was a place in transition. An Indigenous landscape of trails, gathering places, spiritual centres and meeting places in which the Rapids locale the buffalo plains, the crossing and Moosehead figured prominently, was re-placed, given new definition and significance by Metis and European geographies, spatial networks and toponyms. Historical geographers have noticed the transitory nature of place. The creation of place, observes Allan Pred, “always involves an appropriation and transformation of space and nature that is inseparable from the reproduction and transformation of society in time and space.” [48] The acquisition of Rupert’s Land by Canada in 1870 marked the beginning of a new era of appropriation and transformation in the west that reinscribed the landscape of the Rapids locale mostly erasing or obscuring prior inscriptions.

When Canada acquired Rupert’s Land in 1870, Indigenous property rights made treaty-making with the Indigenous peoples of the plains a state priority. [49] The first of the several treaties negotiated with plains Indigenous people was the Stone Fort Treaty of 1871 named after the site of its negotiation, Lower Fort Garry. It was negotiated in August 1871 by veteran HBC officer, former Member of Parliament, and Indian Commissioner Wemyss Simpson, the new Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba, Adams Archibald and Indigenous leaders from south-central Manitoba. After nine days of negotiations, First Nations got promises of land, education, and resources. For these they turned their homeland over to Canada and undertook “to maintain perpetual peace between themselves and Her Majesty’s white subjects, and not to interfere with the property or in any way molest the persons of Her Majesty’s white or other subjects.” [50]

Tim Cresswell has noticed that when something or someone has been judged to be “out of place,” they have crossed a line, frequently a geographical line. [51] By setting out a framework for new property relations in the West, Treaty 1 served as the foundational instrument through which, with the spread of settlement, Indigenous people on the eastern prairies were soon be deemed to be mostly out of place in their former homeland. The Indigenous landscape including the Rapids locale, obscured by Metis and European geographies, would now be overwritten by the geometry of a new commercial and industrial order.

Treaty 1 transformed an Indigenous landscape. It ended the mobile life of Indigenous and Metis people that had given the Rapids locale meaning and significance. Ironically the Treaty perpetuated the memory of the Rapids Crossing by incorporated the site as a place the most westerly point on the Treaty 1 boundary in the Treaty. The boundary began a little west of the Lake of the Woods. It passed to the centre of Whitemouth Lake, headed to the mouth of the Winnipeg River, and travelled west across the south end of Lake Winnipeg and across Lake Manitoba. Then it descended southwest in a straight line to the crossing of the Rapids on the Assiniboine and concluded with a line due south to the International Boundary Line. [52]

The Rapids Crossing is also implicated in Treaty 2. Brandon, on the west side of the Crossing, occupies land relinquished by First Nations under Treaty 2, the Manitoba Post Treaty, so named after the HBC post on Lake Manitoba where it was signed 21 August 1871. Treaty 2 land stretches from the Rapids Crossing west to Moose Mountain in southeastern Saskatchewan, well known to Wemyss Simpson as a winter trading post of the HBC Post at Fort Ellice.

The Rapids Crossing also had a connection with Treaty 4 negotiated at Fort Qu’Appelle. In early August 1874, Ottawa ordered the Winnipeg Rifles to march to Qu’Appelle to be on hand for the treaty negotiations in September. On 17 August 1874, 113 men under the leadership of seven staff officers of the 90th Regiment Winnipeg Rifles, accompanied by 12 double wagons, 15 carts, 46 horses, and a small drove of cattle to provide fresh meat for the journey, set out from Winnipeg to march to Fort Qu’Appelle. West of Portage, the Rifles took the South Trail to the Rapids Crossing. The contingent reached Fort Qu’Appelle on 8 September. [53]

Contemplation of the changed nature of the Rapids Crossing from gateway to boundary would evoke dramatically different narratives from descendants of Indigenous, Metis and settler communities on the eastern prairies. Among Indigenous and Metis descendants, it might well trigger what one writer termed traumatic forms of memory involving a continuing search for recognition of grievous, irrecoverable loss, perpetuated across generations. [54] On the other hand, descendants of those who arrived in the West to settle the commons would almost certainly embrace memories rooted in a narrative of positive material and social progress.

The terms of the Numbered Treaties dealing with Indigenous title to the prairie West marked the beginning of a revolutionary appropriation and transformation of the Canadian prairies. However, surveying, railway construction and settlement took time. The closing of the western commons was a gradual process. As late as 1876, treaty negotiators for Ottawa assured First Nations on the prairies that Ottawa would not “take away your living, you will have it then as you have it now.” [55]

It was not to be. As Irene Spry has explained, the gradual expansion of private property was inimical to the idea that ”A life based on free access to a variety of common resources scattered over a wide territory ... [that] involved continual movement from one base of operations to another according to the season, the migration of game, and traditional ceremonial meeting places.” [56] As late as 1878, the Rapids locale remained unsurveyed and ungranted, but survey crews, land seekers and riverboats on the Assiniboine were unambiguous harbingers of change.

In the summer of 1878, the flow of migrants to the eastern prairies prompted steamboat operators to ascend the Assiniboine to points west of Portage. Travel went well until they reached the Rapids where steamboats could travel no farther. The rocky, gravelly terrain of the Assiniboine delta that furnished a crossing on the Assiniboine for cart traffic proved a barrier to river travellers as it had to those of the fur trade era. Boulders in the bed of the Assiniboine at the apex of the Assiniboine delta presented the most difficult challenge to navigation on the Assiniboine west of the Forks. Rapid City Landing the third feature of the Rapids locale was born at the foot of the Rapids wherecargo and passengers were landed, and transported by cart or wagon to Rapid City.

Not for long. On 15 May 1879, Captain Webber of the steamer Marquette fully loaded with passengers for points above the Rapids and HBC freight destined for Fort Ellice took on the Rapids. To defeat the Rapids, Webber had to put artificial anchors called “dead men” in the side of the river to winch the Marquette over the Rapids. After several hours of hard work, the Marquette arrived above the rapids. [57] Grand Rapids, the principal barrier to navigation on the Assiniboine, had been solved; navigation was open from the Forks to the Qu’Appelle.

For a few more years, Rapid City Landing continued but with a new name: Currie’s Landing, named so by a newcomer to the West. William Currie was a native of Lanark County, Ontario. After brief spells in a merchandise store and the grain trade, he headed west in 1879. The Rapids locale was surveyed in October/November 1880. It occupied Sections 1, 2, 11 and 12 in Township 10 Range 18 West 1. In the notes on the survey certificate for Township 10, it was recorded that William Currie had squatted on portions of Sections 1 and 2, the site of Rapid City Landing and the Rapids. Officially, Currie homesteaded on the northeast quarter of Section 2. [58] Even before his homestead entry was registered, Currie had set about making the place familiar. He renamed the place Currie’s Landing and soon reference was being made to Currie’s Rapids. He established a ferry across the Assiniboine next to the landing. The “deadman” to control the ferry’s progress across the river is still in place on the north side of the Assiniboine.

The Rapids locale and the prairies might be thought of as a palimpsest a surface inscribed over time with meaning sometimes but not always visible on the landscape. This layering process often leaves traces of earlier inscriptions. Martin Kavanagh’s rendering of the Rapids locale in his Assiniboine Basin (circa 1946) illustrates this process of inscribing new toponyms and masking older ones in the course of which places are transformed, and memory obliterated. [59] Kavanagh privileges the most recent toponyms but his sense of history requires that he safeguard prior toponyms by recording them parenthetically in small text. Currie’s Landing and Currie’s Rapids appear in text several times the size of his reference to Grand Rapids that appears in parenthesis. A reference to the Grand Valley Trail appears, but there are no references to the historic Traders’ Road, Hunters’ Track, or Fort Ellice Trail. All vestiges of Indigenous or Metis geographies other than those like Grand Rapids are transmuted into English topynyms.

In the modern history of the prairie West, the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway had the most dramatic impact on reordering of landscape and place.From the early 1870s, routes for the CPR struck northwest to the fertile belt identified by Hind and Palliser. There would be branch lines. In his Report on Surveying Operations West of The Province of Manitoba for the year 1879, Marcus Smith (Sandford Fleming’s second-in-command) suggested a crossing for the Assiniboine “a little above the Grand Rapids” for a southern branch. [60] In his 1880 Report, Sanford Fleming highlighted Smith’s suggestion: the crossing would bring the CPR to a “point commanding a fine agricultural country... [where] an important railway and business centre” might be established.And there was one additional advantage: the land in the area of the crossing was “unsurveyed and ungranted.” [61] When the track was finally laid for the mainline, Smith’s crossing above the Grand Rapids would be the favoured option.

In the late spring of 1881, the new CPR syndicate decided to reroute the line across the southern prairies. There is no simple explanation for the decision though geography seems to have been a central concern. John Macoun, chief botanist for the Geological Survey, had, contra Hind and Palliser, championed the prairies as a settlement frontier. Members of the Syndicate were concerned that a northern route would leave the CPR vulnerable to competition from the US-based Northern Pacific Railway. [62] In the spring of 1881, a southern crossing of the Assiniboine was required and the terrain at the apex of the Assiniboine delta a crossing above the Grand Rapids proved most hospitable to the requirements of the new railway. The rocky level terrain at the end of the Assiniboine valley would serve as the gateway to the prairies for the CPR. [63]

On 15 March 1881, Sir John Macdonald confirmed the new route for the CPR. He did so in response to a question in the House of Commons from Sir Richard Cartwright. Cartwright framed his question to Prime Minister Macdonald obliquely:

Cartwright: “That is, it will pass by what are known as the Assiniboine Rapids?”

Macdonald: “Yes.” [64]

Macdonald’s announcement marks a crucial moment in the history of the Rapids locale and the surrounding prairies. Numbered treaties, surveying, and granting of land had begun the final transition of the prairie commons to private property, imprinting new concepts of property law upon the land. [65] The impact of these developments on the Rapids locale and the West might be compared with those flowing from the reconstruction of Ireland in the wake of the English colonization beginning in the 1500s. Then surveying and mapping served to make Ireland “visible” in new ways, overwriting and making invisible the old order in palimpsest fashion. To borrow from William Smyth, the closing of the commons entailed the commodification of the prairie lands during which places like the Rapids locale were incorporated into “geometric chess pieces to be traded like stocks and shares.” [66]

The construction of the CPR added a new urgency to this process of transformation. Its arrival on the eastern prairies introduced a new order of transportation. Privatization of land and steel rails closed prairie trails and the prominence of the Rapids local as a crossroads on the prairies was undermined as the former mobile life of the region ended. Though sternwheelers would ply the Assiniboine until the early 1880s, the curtains were closing on the old west. The Rapids, prominent on the sketchy maps of HBC man Peter Fidler in the early 1800s, the sophisticated cartography of the Hind and Dawson Expedition, and those generated by the CPR’s Sandford Fleming, soon disappeared from maps of the new Manitoba.

Beginning in the late-18th century, a three-mile section on the Lower Assiniboine came to prominence as the Grand Rapids on the Assiniboine. Through the 19th century, the Rapids emerged as a locale involving the Rapids, a Crossing above the Rapids and, in the 1870s, a landing at the foot of the Rapids. This locale/place was a crossroads of trunk trails and river transport on the eastern prairies. The dramatic rupture in prairie history culminating in the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway transformed the Grand Rapids locale into a largely anonymous location on the Assiniboine River, a degraded landscape at the eastern tip of the city of Brandon, bereft of most of any mnemonic burden.

1. See Tim Cresswell, Place - A Short Introduction, Blackwell: Oxford, 2004, pp. 15-49; Terrance Young, “Place Matters,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 91, No. 4 (December 2001), p. 681; Allan Pred, “Unglorious Isolation or Unglorious Misrepres(s)entation,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 75, No. 1 (March 1985), pp. 132-133.

2. Edward S. Casey, The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997, p. 286.

3. J. E. Malpas, Place and Experience a Philosophical Topography, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 36.

4. I have created a documentary account of the Grand Rapids locale. It may be viewed online at https://vimeo.com/205805560 with password: rapids

5. Tim Cresswell, Place, pp. 8-10.

6. C. Tilley, A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments, Oxford: Berg, 1994, p. 33.

7. Reuben Rose-Redwood, Derek Alderman and Maoz Azaryahu, "Geographies of toponymic inscription: new directions in critical place-name studies," Progress in Human Geography 34(4) 2010, pp. 453-470; and John C. Lehr and Brian McGregor, "The politics of toponymy: Naming settlements, municipalities and school districts in Canada’s Prairie provinces," Prairie Perspectives: Geographical Essays, 2016, 18: 78-84.

8. On this theme see Sian Jones, ”Thrown Like Chaff in the Wind': Excavation, Memory and Negotiation of Loss in the Scottish Highlands,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 16 (2012), 346-366.

9. Thank you to Rod McGinn and Dion Wiseman for the instructive field trip to the Assiniboine delta. On the origins of the Assiniboine delta: see A. E. Kehew and M. L. Lord, “Glacial-lake outbursts along the mid-continent margins of the Laurentide ice-sheet,” in Catastrophic Flooding, L. Mayer and D. Nash, eds., Boston: Allen Unwin, 1987, pp. 95-120; and Brent Wolfe and James T. Teller, “Sedimentation in Ice-Dammed Glacial Lake Assiniboine, Saskatchewan, and Catastrophic Drainage Down the Assiniboine Valley,” Geographie physique et Quaternaire, 49, 2, 1995, 251-263.

10. George Colpitts, Pemmican Empire: food, trade, and the last bison hunts in the North American plains, 1780-1882, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 61-62.

11. Etienne Rivard, “Colonial Cartography of Canadian Margins: Cultural Encounters and the Idea of Metissage,” Cartographica. 43,1 (Spring2008), pp. 45-66.

12. Mr. John McDonnell, “Some Account of the Red River with Extracts from His Journal 1793-95,” in L. R. Masson, Les Bourgeois de la Compagnie du Nord-Ouest (Quebec 1889), p. 273. Original Digital images, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library.

13. Robert Goodwin, 18 September 1800, Brandon House Post Journal, 1800-1801, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives (hereafter HBCA) B22/a/8.

14. Mr. John McDonnell, “Some Account of the Red River,” p. 273.

15. Henry Youle Hind, Narrative of the Canadian Red River Exploring Expedition of 1857 and of the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition of 1858, Vol. 1, London: Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1860, pp. 181, 306. See also John Rae’s reference to Metis guide James Mackay in Irene Spry, “A Visit to Red River and the Saskatchewan, 1861”, by Dr. John Rae, FRGS. The Geographical Journal, Vol. 140, No. 1 (Febuary 1974), p. 10.

16. Peter Fidler, “Journal of a Journey from Swan to the Red River and down it in a canoe from the Elbow to its entrance into Lake Winnipeg & along its South & Eastern Shores to its Discharge into the Elongation of the Saskatchewan River or Nelson’s River.” 29 March 29 September 1808, Peter Fidler fonds, HBCA E.3/3 fos. 51d-66d.

17. Peter Fidler, Sketch map by “Mr John McDonald AMFCo [American Fur Company] 1808 Red River & its communications,” in Peter Fidler’s journals of exploration and survey, 1809 (E.3/4) Peter Fidler fonds, HBCA.

18. Peter Fidler, “A Map of Red River District 1819” in Brandon House and Upper Red River District reports, Red River District report, 1819, HBCA B.22/e/1.

19. On the creation of Brandon House in 1793 see Harry W. Duckworth, “The Madness of Donald Mackay,” The Beaver 68, no. 30, (June/July 1988), 25-42.

20. Robert Goodwin, Postmaster, Brandon House Post Journal, April 23, 1795, HBC Archives, B.22/a/2,3. For biographical notes on Cadott, Beaubien, and Rocheblave see Harry W. Duckworth, “The Last Coureurs de Bois,” The Beaver, Spring 1984: 4-12.

21. On this theme see J. B. Tyrrell, “Algonquian Indian names of places in northern Canada,” Transactions of the Royal Canadian Institute 10(2) 213-231.

22. Translate Ojibwa cites Brandon as one of several meanings of Baawitigong. See http://www.translateojibwe.com/en/dictionary-ojibwe-english/Baawitigong. Email communication Audrey L. Cook.

23. Email communication from Norman Bone, Chief, Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation, 9 September 2016.

24. See for example Laurie’s Map of the North-West Territories Shewing the Surveys now made, and the Railway and other Routes thereto. Compiled by D. Codd, Ottawa. 1870. Scale 1 inch to 25 miles. Lithographed by Roberts, Reinhold & Co., Lith., Montreal. Wyman Laliberte, Historical Maps of Manitoba, https://www.flickr.com/photos/manitobamaps/2231443980

25. Robert Goodwin, Postmaster, Brandon House Post Journal, correspondence from William Mackay, North West Company master, Portage la Prairie, 28 November 1794, HBCA B.22/a/2,3.

26. On Indigenous geographies see David Meyer and Dale Russell, “Though the Woods Whare Thare Ware Now Track Ways,” Canadian Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 31, No. 3, 2007, 163-197.

27. “A Map of Hudsons bay and Interior Westerly particularly above Albany 1791...” by Edward Jarvis and Donald McKay, HBCA G.1/13.

28. On 23 May 1805, John Mackay reported that 40 tents of Cree and Assiniboine had left for the Moosehead to conjure. John Mackay, Brandon House Post Journal, 1805-1806, HBCA B/22/a.

29. Peter Fidler, Surveyor and District Manager, Brandon House Post Journal, 1 June 1818, HBCA A.30/15, 16. In the 1860s, Dakota people led by Standing Buffalo camped at the Rapids and employed the crossing for travel to the Missouri. Mark Diedrich, The Odyssey of Chief Standing Buffalo, Minneapolis: Coyote Books, 1995, p. 69.

30. For a geological account of the crossing site see Brent Wolfe and James T. Teller, 1995, “Sedimentation in Ice-Dammed Glacial Lake Assiniboine, Saskatchewan, and Catastrophic Drainage Down the Assiniboine Valley,” p. 252.

31. Nicole St-Onge, Carolyn Podruchny, and Brenda Macdougall, eds., Contours of a People Metis Family, Mobility and History, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014, p. 9.

32. Alexander Ross, The Red River Settlement: its rise, progress, and present state, with some account of the native races and its general history to the present day, London: Smith Elder, 1856, pp. 244-245.

33. Henry Youle Hind, Reports of Progress together with a preliminary and General Report..., p. 106.

34. For Chaplin and Johnstone see Bailey’s Monthly Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, Vol. 10, No. 70, September 1865, 215-217 and November 1865, 323-24. Hathi Trust Digital Library, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/010308010. For Rae’s account of the journey see Irene Spry,“A Visit to Red River and the Saskatchewan, 1861”, by Dr. John Rae, pp. 2-3. For coordinates see Table p. 5, Rae at Assiniboine Rapids, 10. A typographical error is apparent in the table reference to the Rapids site.

35. Marcus Smith, Report of Surveys and Explorations Between Red River and the South Saskatchewan, February 25th, 1880 in Sandford Fleming, C.M.G, Engineer in Chief, Report and Documents in Reference to the Canadian Pacific Railway, Ottawa, Maclean Roger & Co, 1880, p. 252.

36. Map of the Country to be Traversed by the Canadian Pacific Railway to Accompany progress Report on the Exploratory Surveys [map] 1:4435200. In Sandford Fleming, Report on the Surveys and Preliminary Operations on the Canadian Pacific Railway up to January 1877 (Ottawa: 1877), Sheet No. 1.

37. D. M. Loveridge and Barry Potyondi, From Wood Mountain to the Whitemud: a Historical Survey of the Grasslands National Park Area, Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1983, 15.

38. Report of Inspector A. B Steele, Qu’ Appelle, November 3, 1880, p. 43, Commissioner’s Report, 1880, North-West Mounted Police, Sessional Papers, Dominion of Canada, Vol. 3, 1881, Ottawa: MacLean, Roger & Co, 1881.

39. Mrs. Dougald McVicar, Reminiscences of Early Brandon, Assiniboine Historical Society Collection, CA DHM 14, Box 1, Daly House Museum.

40. Beecham Trotter, A Horseman and the West, Toronto: Macmillan Co. of Canada, 1925, pp. 42-43.

41. Barry Kaye and John Alwin, “The Beginnings of Wheeled Transport in Western Canada,” Great Plains Quarterly, 4 (Spring 1984), 121-134.

42. H. Warre, Overland to Oregon in 1845 (Ottawa: Public Archives of Canada, 1976), p. 28 in Scott Hamilton, “The Fort Ellice Area: Pre-Excavation Research From An Archaeological Perspective,” (Unpublished Report prepared for the Historic Resources Branch, Manitoba). A copy is held at the Daly House Museum, Brandon.

43. W. B. Cheadle, Cheadle’s Journal of a Trip Across Canada 1862-63, Tutland: Charles E. Tattle Co., 1971, pp. 53-54.

44. Marcus Smith, Report of Surveys and Explorations Between Red River and the South Saskatchewan, to Sandford Fleming, February 25th, 1880 in Sandford Fleming, C.M.G, Engineer in Chief, Report and Documents in Reference to the Canadian Pacific Railway, Ottawa: MacLean, Roger & Co, 1880, p. 252.

45. Lindsay Russell, “Map of Part of the Northwest Territory Shewing the Operations of the Special Survey of Standard Meridians and parallels for Dominion Lands.” Department of the Interior, Report on the Department of the Interior for the Year 30th June, 1878. Sessional Papers #6 vol. 12. Ottawa: Dominion Lands Office, 1878.

46. Issac Cowie, A Narrative of Seven Years in the Service of the Hudson’s Bay Company 1867-1874 on the Great Buffalo Plains, Toronto: William Briggs, 1913, pp. 427-428.

47. "Trail Distances from Portage la Prairie to Fort Ellice, via the Rapids of the Assiniboine River, 37" in Part 1 of Report of Department of the Interior, December 31, 1879 in Annual Report of the Department of the Interior for 1878, Ottawa: MacLean, Roger & Co, 1879.

48. Allan Pred, “Place as Historically Contingent Process: Structuration and the Time-Geography of Becoming Places,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 74, No. 2 (3 June 1984), 279.

49. Indigenous people had made it clear that the West belonged to them. When rumours circulated that the HBC had put a For Sale sign on Rupert’s Land, Chief Peguis of the Red River Ojibwa objected in a letter to the British Parliament that the HBC had “never arranged with me for our lands. We never sold our lands to the said Company, nor to the earl of Selkirk....” See “Native Title to Lands,” The Nor’Wester, 14 February 1860, p. 3.

50. Copies of the Treaties (1 and 2) Made 3rd Day and 21st Day August 1871 Between Her Majesty the Queen and Chippewa and Cree Indians of Manitoba and Country Adjacent, Ottawa: MacLean, Roger & Co., 1879, p. 5.

51. Tim Cresswell, Place, p. 103.

52. Copies of the Treaties, (1 and 2) Made 3rd Day and 21st Day August 1871, p. 4.

53. Captain Ernest J. Chambers, The 90th Regiment A Regimental History of the 90th Regiment Winnipeg Rifles, Winnipeg, 1906, p. 36

54. On the concept of traumatic forms of memory see S. Feuchtwang, “Loss: Transmissions, recognition, authorisations,” in Regimes of Memory, S. Radstone and K. Hodgkin, eds., London: Routledge, 2003, pp. 76-90.

55. Alexander Morris, The Treaties of Canada With The Indians, Toronto: Fifth House Publishers, 1991, p. 65

56. Irene Spry, “The Great Transformation: The Disappearance of the Commons in Western Canada,” in Man and Nature on the Prairies, Canadian Plains Studies 6, Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina, 1976, pp. 33-34.

57. Roy Brown, Steamboats on the Assiniboine, Brandon: Tourism Unlimited, 1981, pp. 26-27.

58. Search William Currie, Land Grants of Western Canada, 1870-1930, https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/land/land-grants-western-canada-1870-1930/Pages/search.aspx

59. Martin Kavanagh, The Assiniboine Basin a social study of the discovery, exploration, and settlement of Manitoba, Winnipeg: Public Press, 1946, p. 125.

60. Marcus Smith, "Report on Surveying Operations West of The Province of Manitoba for the year 1879, 14" in Canadian Pacific Railway, Reports in Reference to Location Second Section West of Red River, 1880.

61. Sandford Fleming, Chief Engineer Report and Documents in Reference to the Canadian Pacific Railway, Ottawa: MacLean, Roger & Co., 1880, p. 248.

62. W . A. Waiser, “A Willing Scapegoat: John Macoun and the Route of the CPR,” Prairie Forum, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Spring 1985), p. 66.

63. Terrance Young, “Place Matters,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 91, No. 4 (Decmber 2001), p. 681.

64. Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 15 March 1881, p. 1400.

65. Irene Spry has observed that this transition entailed “the tragedy of the disappearance of the commons on the prairies ...” Irene Spry, “The Great Transformation: The Disappearance of the Commons in Western Canada,” in Man and Nature on the Prairies, Canadian Plains Studies 6, Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina, 1976, p. 21.

66. William Smyth, Map-Making, Landscapes and Memory: A Geography of Colonial and Early Modern Ireland, c.1530-1750, Cork: Cork University Press, 2006, p. 455.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 6 September 2022