MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1956-57 season

|

Though not the first to fill the office of Chief Justice in Manitoba, Hon. Edmund Burke Wood was the first to settle into the duties and responsibilities of the position. The first Chief Justice in this province, or, perhaps, it should be said, the first person to bear the title of Chief Justice, to have the shadow of office without the substance, was James Ross; a man of many parts but only nominally a lawyer, to whom Margaret McWilliams refers, in Manitoba Milestones, as “the most brilliant and assertive of the Selkirk descendants of that day.” He was appointed Chief Justice by the provisional government of Louis Riel. As events turned out, his appointment was not of much practical consequence in the legal history of the province. After the birth of Manitoba as a Province of Canada, Hon. Alexander Morris was appointed the first Chief Justice, but he had just embarked upon his judicial duties when he resigned to take up an appointment as Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. Hon. Edmund Burke Wood was his successor.

Though not the first to fill the office of Chief Justice in Manitoba, Hon. Edmund Burke Wood was the first to settle into the duties and responsibilities of the position. The first Chief Justice in this province, or, perhaps, it should be said, the first person to bear the title of Chief Justice, to have the shadow of office without the substance, was James Ross; a man of many parts but only nominally a lawyer, to whom Margaret McWilliams refers, in Manitoba Milestones, as “the most brilliant and assertive of the Selkirk descendants of that day.” He was appointed Chief Justice by the provisional government of Louis Riel. As events turned out, his appointment was not of much practical consequence in the legal history of the province. After the birth of Manitoba as a Province of Canada, Hon. Alexander Morris was appointed the first Chief Justice, but he had just embarked upon his judicial duties when he resigned to take up an appointment as Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. Hon. Edmund Burke Wood was his successor.

In 1871, the first Legislature of Manitoba passed an act establishing a Supreme Court for the province. This Court, the ancestor of our present courts, was a court of original and appellate jurisdiction, having all the powers incident, by the laws of England, to Superior Courts, both civil and criminal: or, in Chief Justice Wood’s own words, it was a court “combining and blending within itself as one Court, equity, common law, probate and every other jurisdiction possessed and exercised by all or any of the Superior Courts of law, equity and probate in England on the 14th July, 1870.” It was to be presided over by a judge to be designated “The Chief Justice” and was to sit four times a year in Winnipeg and at such other times as the Lieutenant Governor might direct.

In 1872, the name of this Court was changed to the Court of Queen’s Bench and its membership was increased to three, a Chief Justice and two puisne judges. A single judge was to preside, except when the court sat as a Court of Error and Appeal, when two judges should form a quorum. Alexander Morris was appointed Chief Justice on 2 July 1872, and in October of the same year, James McKeagney and Louis Betournay were appointed to fill the other two positions on the Court.

Chief Justice Morris resigned on 1 December 1872, and the position of Chief Justice was vacant until the appointment of Edmund Burke Wood on 11 March 1874.

Why was neither of the puisne judges promoted to Chief Justice on Morris’s resignation? Whatever other reasons there may have been, one good and sufficient reason was that there was general dissatisfaction with their work as judges. During the fourth session of the first Provincial Legislature Attorney-General Henry James Clarke spent part of two days berating them as judicial weaklings. A political fire-brand, of few fixed principles, Clarke had a bitter, scolding tongue. Dr. John H. O’Donnell, in his book Manitoba As I Saw It says of him: “Attorney General Clarke made himself unpopular early. He no sooner assumed office than he felt he was the law, instead of legal director, and so expressed himself.” Clarke’s remarks had generally to be made subject to a discount. A more reliable source that expressed dissatisfaction with the work of Justices McKeagney and Betournay was the Manitoba Free Press which said, in an editorial in its issue of 22 November 1873: “Ten o’clock is the hour at which the Court is supposed to open; rarely, however, does this take place before eleven, and sometimes indeed not till much later. Seldom then does it sit more than an hour before there will be an intermission of from two to four hours, known in Court parlance, as a ’half-hour’s recess.’ After this, perhaps a couple of hour’s work will be done, and then the Court will be adjourned till tomorrow at ten o’clock.”

Edmund Burke Wood, the man who was to bring the Court into somewhat better repute, was born on 13 February 1820, near the Village of Fort Erie, in the County of Welland. His father, Samuel Wood, was a farmer who left Ireland for the United States at the turn of the nineteenth century and moved to Upper Canada after the War of 1812. Wood was educated at local public and high schools. A good student, he set his sights on a university education, and after many delays, made necessary by a limited family budget, he graduated from Oberlin College, Ohio, in his twenty-eighth year, with the degree of BA.

After his graduation, he taught school in the township of Beverly, County of Wentworth. He soon found that he had mistaken his calling. Teaching in a country school soon raised in him the seeds of discontent. He disliked its slow, steady drudgery, and it did not offer an avenue for advancement rapid enough to suit him. He was born with a goodly dose of ambition. Lawyers were then the most influential and prominent members of their communities. Alexis de Tocqueville had written a few years before this time: “In America lawyers form the highest political class and the most cultivated circle of society ... If I were asked where I would place the American aristocracy I should reply without hesitation that it is not composed of the rich ... but that it occupies the judicial bench and bar.” And as it was in America, so was it in Canada. Thus Wood turned to the law, intent on finding a career which would offer ample scope for his ambition. In Easter Term, 1848, he was admitted as a student-at-law on the Common Roll of the Law Society of Upper Canada. At the same time, he entered the law offices of Freeman and Jones, in Hamilton, as an articled clerk. Later he transferred his articles to Archibald Gilkison of Brantford with whom he completed his service as a law student. After satisfying his examiners that his time under articles had been spent to some purpose, he was admitted as an attorney on 21 November 1853.

Brantford was the county seat of the recently formed County of Brant. Soon after he had qualified as a solicitor, Wood was offered an appointment as Clerk of the County Court and Deputy Clerk of the Crown for the new county. Gratefully, he accepted this position, as it meant a small but steady income; but when it became apparent that it would interfere with his prospects in his profession, he promptly resigned office. He was called to the Bar in Trinity Term, 1854, at the age of thirty-four. This was rather a late start but Wood entered upon his career at the Bar determined to make up for lost time.

After practising for a short time by himself, he formed a successful partnership with Peter Ball Long. There was plenty of room in the profession and the new firm was soon flourishing. Wood handled the firm’s court work, and his partner looked after the office work. This was an ideal arrangement for Wood’s real interest was in advocacy. He enjoyed the heat of forensic battle. His blunt way of speaking and his forceful personality made him a formidable jury advocate and he soon became a well-known figure before the juries of half-a-dozen counties. His rapid advancement in his profession was aided by his prodigious industry. Never at the Bar, nor on the Bench, did he show the slightest fear of work.

In April 1855, Wood married Jane Augusta Marter, a daughter of Dr. Peter Marter, of Brantford. They had a numerous brood of children. One of their sons, Edmund Marter Wood, was called to the Bar of Manitoba in 1882, and six years later entered the service of the Provincial Government. When he retired in 1930, after 42 years as a civil servant, he had seen much history in the making, having served under the administrations of six Manitoba premiers: Hon. David H. Harrison, Hon. Thomas Greenway, Sir Hugh John Macdonald, Sir Rodmond P. Roblin, Hon. T. C. Norris, and Hon. John Bracken.

As a lawyer whose future depended solely upon his own efforts, Wood kept his eyes open for a good business opportunity. One came to him finally. He helped to promote the Buffalo and Lake Huron Railway Company which constructed a line through Brantford, connecting Buffalo with Goderich. He became solicitor for this company and was engaged on its behalf in many important law suits. Perhaps, his most important case at the Bar was the Chancery suit of Whitehead v. The Buffalo and Lake Huron Railway Company. The managing director of the company entered into a contract with Whitehead, a railway contractor, in his own name, adding after his signature the words `acting in behalf of the company.’ When Whitehead had completed most of the work called for in this contract, the company repudiated it, alleging that the contract was not under the seal of the company and that the prices agreed to be paid were exorbitant. Whitehead promptly entered a bill in Chancery. After a lengthy trial, the Court ruled that the company was bound by the contract and this ruling was upheld in the Court of Appeal. Wood was on the losing side but his handling of this case added greatly to his reputation at the Bar.

When his success at the bar was assured, Wood became anxious to get into the political swim. His opportunity came when he was nominated by the Liberals to contest the constituency of South Brant in the general election of 1863. His opponent was Rev. William Ryerson.

Wood threw himself into the fray with great energy and carried the constituency by a comfortable majority. In Parliament he supported the Macdonald-Dorion Government. At the first general election after Confederation, he was returned for the Riding of South Brant to both the House of Commons and the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. When an act was passed abolishing dual representation, Wood elected to sit in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. When Hon. John Sandfield Macdonald was called upon to form a “no party” administration in Ontario, he invited Wood into his Cabinet as Provincial Treasurer. Wood was the only member of the Government who could be called a Liberal. His party was strongly opposed to coalition and, by his acceptance of office, he came into disfavour with former political friends. Contemporary reports of Wood’s political activities say that he was a successful Provincial Treasurer and that his budget speeches were models of what such speeches should be.

In the Dominion Parliament, Hon. Edward Blake was leader of the Opposition, with Hon. Alexander Mackenzie as his first lieutenant; a powerful combination and they pressed Macdonald with great vigour. “The Government of Ontario,” they charged, “had been from the first the mere creatures of the Dominion Government, existing by its sufferance and subject to its control.” By their repeated attacks they brought about a crisis in the affairs of the Government. In December 1871, while the Government was fighting for its existence, Wood resigned his portfolio, but continued to sit in the Assembly as a private member. For letting expediency be his guide he was severely censured by those who stood by Macdonald’s political ship until it went down in defeat, but he came back into favour with the leaders of the Liberals.

In the Dominion election of 1872, Hon. Edward Blake was returned to the House of Commons for both West Durham and South Bruce. He elected to sit for South Bruce. Wood was pressed into service by the Liberals to stand for West Durham. He resigned from the Ontario Legislature and was returned to the House of Commons for West Durham by acclamation. As a member of the Commons he took part in the attacks on Sir John A. Macdonald and his Cabinet over the Pacific Scandal. A debater of skill and vigour, he struck several damaging blows on behalf of his party. One day, in the House of Commons, he ventured upon prophecy. “Before many days,” he said, “the Government will have fallen like Lucifer, never to rise again.” The first part of this prophecy came to pass but he had not reckoned on the immense political vitality of Sir John A. Macdonald whose fall was only temporary. He was in the full stride of his parliamentary career when he was appointed Chief Justice in Manitoba, 11 March 1874. Shortly before his elevation to the Bench, he had been appointed a Queen’s Counsel and elected as a Bencher of the Law Society of Upper Canada.

Before he could preside over the Manitoba Court, Wood had to become a member of the Provincial Bar. This presented no great hazard at that time. He was admitted to the practice of law in Manitoba by the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council on 9 June 1874, under the provisions of an Act passed at the first session of the Legislature “to regulate the admission to the study and practice of law in the Province of Manitoba.” The June assizes opened the day after his admission but he was unable to preside over the Court. The long, tedious journey from the East had exhausted him and he was forced to rest for several days after his arrival in Winnipeg. He took his seat as a judge for the first time on Monday, 15 June 1874. At the opening of Court, Attorney-General Clarke and Hon. Joseph Royal, speaking on behalf of the Bar of Manitoba, the one in English and the other in French, congratulated him on his appointment as Chief Justice. In reply to their remarks, he said, in part, as reported in The Manitoban for 20 June 1874:

“Respect for the Bench, and confidence in its decisions, were the first principles to be established in every Court. Where they were lacking it was impossible that the Bar could be prosperous or even maintain its standing among the learned professions. It was his opinion that in a new country like ours it should be the object of judges and legislators to form a code by which the law could be administered in its simplest and most effective form, and he would take the earliest opportunity of bringing the attention of the Provincial Legislature to the subject. He had looked into the laws already framed and in operation in the Province, and was much pleased with the work already done; he had come to this country reluctantly and with many misgivings, but he was happy to say that all his apprehensions had disappeared on his arrival in this beautiful country. He was very much pleased with what he had seen of the Province and its people and was resolved to make it his home for life.”

This, then, was the note upon which Chief Justice Wood embarked upon his judicial duties. He expressed a very worthy sentiment when he spoke of respect for the Bench. But there is an onus on the Bench to make itself worthy of respect. Unfortunately, during his years in judicial office, Chief Justice Wood did not always discharge this onus.

As Dr. Samuel Johnson once remarked: “A man may be very sincere in good principles without having good practice.” Whatever may have been his principles, and however sincerely he may have held them, the hard fact remains that neither in his private, nor in his professional life, was Wood’s practice always above reproach.

Thus in January 1877, when he had served as Chief Justice for less than three years, things had come to such a pass that Lieutenant-Governor Morris was called upon to write a formal letter to the Secretary of State at Ottawa, enclosing a copy of a Minute of the Executive Council of Manitoba, reporting Chief Justice Wood for acts of public intoxication. Other shortcomings, equally serious in a judge, whose faults, unlike those of ordinary mortals, are never to be borne lightly, will be noticed later.

The first case that engaged Chief Justice Wood’s attention was, in point of historic interest, the most important case that ever came before him. This was the trial of Ambrose D. Lepine, who had been Louis Riel’s second-in-command during the Red River Resistance.

Lepine had been arrested in September 1873, by three special constables. After the Grand Jury had found a true bill, the following indictment was laid against him:

CANADA

Province of Manitoba

Court of Queen’s Bench

Crown SideNovember Term, 1873.

The Jurors for Our Lady the Queen, upon their oath present: That Ambrose Lepine on the fourth day of March in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and seventy, at Upper Fort Garry, a place then known as being lying and situate in the District of Assiniboia in the Red River Settlement in Ruperts Land and now better known as being lying and situate at Winnipeg in the County of Selkirk in the Province of Manitoba, Dominion of Canada—Feloniously wilfully and of his malice aforethought did kill and murder one Thomas Scott: against the form of the statute in such case made and provided and against the Peace of our said Lady the Queen Her Crown and Dignity.

“Henry J. Clarke,”

Q.C. Attorney General.

Lepine appeared before the Court on this indictment at the November assizes, 1873, with Mr. Justice McKeagney presiding. He was represented by Hon. Joseph Royal and Hon. Joseph Dubuc who objected to the jurisdiction of the Court to try their client as his alleged offence had been committed on 4 March 1870, before the Court had been established. On behalf of the Crown, Attorney-General Clarke demurred to this plea. Mr. Justice McKeagney reserved judgment. At the next assizes, held in February 1874, he announced that he did not intend to give judgment until the following term, as he did not think himself competent or justified in deciding a question of such importance. The truth of the matter seems to be that he was shirking the case, that he knew there was a strong public feeling in favour of Lepine and doubted the wisdom of bringing him to trial at a time when passions aroused by the recent trouble in Red River were beginning to subside.

At the June Term of the Court, in 1874, the argument on the question of jurisdiction was had de novo before Chief Justice Wood and the two puisne judges. After hearing lengthy arguments, the Chief Justice gave his decision without leaving his seat. The following note appears in the Court Records kept by Daniel Carey, then Prothonotary of the Court: “His Lordship Chief Justice Wood gave judgment of the Court in the question of jurisdiction in re Ambrose D. Lepine. Plea to jurisdiction disallowed. Their Lordships Judges McKeagney and Betourney [sic] concurring in the judgment.”

When their objection was overruled, Lepine’s counsel moved for a stay of proceedings to enable the defence to summon its witnesses. On Tuesday, 13 October 1874, thirteen months after his arrest, “Ambrose D. Lepine was put to the bar on his trial for murder,” before Chief Justice Wood and a mixed jury. In the meantime. Dubuc had been appointed Attorney-General of Manitoba and was therefore not available for the defence. Hon. Joseph Royal and J. A. Chapleau of the Quebec Bar appeared for the prisoner and Francis E. Cornish and Stuart Macdonald for the Crown.

As the trial got under way, The Manitoban struck a hopeful note. “The course of Manitoba jurisprudence,” it declared editorially, “has for some time required somebody to rescue it out of its lethargic condition, and we hope that that somebody has arrived in the person of Chief Justice Wood.”

The Court sat for ten days, between 13 and 24 October, hearing seventeen witnesses for the Crown and twelve for the defence. Many of these witnesses were men of position and influence in the community. Among those who appeared for the Crown were Rev. George Young, Right Rev. Robert Machray, Alexander Murray, and Hon. Marc A. Girard; and for the defence, Thomas Bunn, Right Rev. John McLean, Andrew G. B. Bannatyne, Senator John Sutherland and Archbishop Tache. After the evidence had been heard, Royal addressed the jury in English and Chapleau in French for the defence and Cornish in English and Macdonald in French for the Crown.

On Monday, 26 October, Chief Justice Wood charged the jury in English and his charge was translated into French by the Clerk of the Crown and Pleas. It was a strong charge, leaning heavily against the defence and leaving the jury no doubt as to what verdict the Chief Justice expected it to bring in.

The jury retired at 4:30 o’clock and returned at 7 o’clock with the verdict—“Guilty with a recommendation to mercy.”

On 28 October, the Chief Justice passed the following sentence, as appears from the Court Records:

“That you Ambrose D. Lepine be taken from the place Where you now stand to the common Gaol of the Province of Manitoba, at Winnipeg, and be there kept in solitary confinement until the 29th day of January in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and seventy-five between the hours of eight and ten o’clock in the forenoon when you shall be taken thence to the place of execution and be there hanged by the neck until you are dead. And may God have Mercy on your Soul!”

Contemporary public reaction to this verdict may be summed up in the words of an editorial which appeared in the Nor’Wester for 2 November 1874:

“The jury having returned on Tuesday evening a verdict of ‘guilty with a recommendation to mercy,’ on Wednesday Ambrose Lepine was sentenced to be hanged on the 29th January next. His Lordship, in passing sentence, intimated to the prisoner that he did not feel warranted in holding out any hope of a reprieve.

The result of this protracted trial has shown that a Manitoba mixed jury can be depended upon to come to a right decision upon evidence and facts. In this case the general impression assuredly was that the jury would not agree but the evidence and the charge of the Judge was so clear and forcible that disagreement was rendered next to impossible.

That the extreme penalty of the law may not be carried out in this case we believe is the wish of nearly all who have expressed an opinion upon the case. The manly manner in which Lepine stood his ground and faced the consequence is in striking contrast to the action of his principal, Riel, who evidently has not the (courage) possessed by the condemned.”

Lepine did not hang. Four days before the date set for his execution, the Governor-General, the Earl of Dufferin, on advice from the Imperial Cabinet, commuted the sentence to two years’ imprisonment.

When he had disposed of the Lepine case, Chief Justice Wood embarked upon the trial of Andre Nault who had been in charge of the Scott firing squad. His trial followed the same pattern as Lepine’s but a better fate awaited him. In the Prothonotary’s book appears this entry under date of 3 November 1874: “The jury came into Court and stated by their foreman that they could not agree, and that there was no prospect of their agreeing. They were then discharged by the Court.”

Some months later, on motion of Attorney-General Dubuc a nolle prosequi was entered in the case against Andre Nault.

When Wood arrived in Winnipeg to take up his judicial duties, this City was a frontier settlement, just beginning to give definite promise of better things to come. According to the first issue of the Manitoba Free Press, published on 9 November 1872, Winnipeg’s population at that time was 1,467 persons, 1,019 males and 448 females. During the next decade, the population climbed slowly but steadily. The census returns for 1881 (the year before Wood died) give Winnipeg’s population as 7,085 and the population of Manitoba as 65.954.

Small as was Winnipeg’s population during his years on the Bench, it was sufficiently large and litigious to present Chief Justice Wood with a great variety of legal problems. Horse stealing, cases concerning the sale and purchase of half-breed land scrip, the illicit sale of liquor to Indians, inquiries into the title to lands that might have changed hands half-a-dozen times without a scrap of paper to evidence any of the transactions—these were some of the problems that came regularly before him.

In discussing with me the early history of the legal profession in Manitoba, the late A. J. Andrews QC, whose memory went back to the early 1880s when he arrived in Winnipeg to study law, maintained that Hon. E. B. Wood gave up a promising career in politics and at the Bar of Upper Canada, and accepted the appointment of Chief Justice in Manitoba, then at the back of beyond, because he was in financial difficulties, a situation brought about by his devotion to politics and his neglect of his law practice. Wood’s financial difficulties continued after his arrival in this province. An easy spender, who had long since forgotten early habits of thrift, he did not live within his income of $5,000.00 yearly. Rumours of his improvidence soon filtered to Ottawa. On 11 December 1874, Prime Minister Mackenzie wrote to Lieutenant-Governor Morris seeking information about these rumours. “I was informed,” he wrote, “that Judge Wood had allowed himself to get deeply in debt to Mr. Schultz. I hope this is not true as I would not doubt that person had purposely intended to lay the Judge under obligations to him. It is a delicate subject to touch but I would like to know if you heard this.”

Morris replied to this enquiry on Christmas Day 1874. “As to the Chief, I fear he is in deep water. I know he had no means when he came here. He then bought from Schultz a lot and unfinished home, which the latter was to finish for him, but eventually Wood took it into his own hands and completed it. It must have cost $7,000.00 or $8,000.00 and unless his brothers helped him, which I doubt, I fear the popular impression is too true, that he is heavily indebted to Schultz.”

In his correspondence with Morris, Mackenzie returned to this subject on 28 May 1875. He then wrote: “I am much concerned about the position Chief Justice Wood has got himself into. I fear greatly it will get worse unless something can be done. Are you able to speak to him? I mentioned the matter with some degree of fullness to Mr. Blake the other day and I would feel obliged by your writing Mr. Blake on this particular subject. Mr. Wood sent me a distressing telegram a few days since about his personal affairs. It is, however, quite impossible for me to do anything except to slightly increase the allowance for travelling expenses, which has been done.”

Once again Mackenzie returned to Wood’s troubles. Writing to Morris on 22 September 1875, he said: “I regret extremely the foolish course of the Chief Justice. You will remember that I asked you if possible to convey a warning to him on this very point, as I foresaw from the first that serious trouble would be sure to arise from his relations to Schultz.”

It thus appears that Wood brought to his judicial labours a mind clouded by financial worries. Never a man of even temper, his personal worries did not improve his disposition. Lawyers soon learned that it was not always a pleasant experience to appear in his court.

One of the lawyers who appeared frequently before him was his nephew, S. C. Biggs QC, a shrewd defence counsel, a master of the rough and ready tactics of those more robust days. In June 1876, Biggs defended three Americans—George M. Bell, Philander Vogle and James Hughes—who appeared in his uncle’s court charged with murder. Three years earlier fourteen Americans, armed with the latest in repeating rifles, had crossed into the Northwest Territories from Montana searching for horses which they claimed had been stolen by Indians. At Cypress Hills a pitched battle took place between the Americans and a party of Indians in which four of the Indians were killed. The Americans fled to their own side of the line. Extradition proceedings were taken by the Canadian Government but were not successful. Later, three of the Americans were arrested while visiting on Canadian soil and brought to Winnipeg to stand trial.

Biggs challenged every white juryman on the jury panel. The Chief Justice did not approve this course and did not hesitate to let his nephew know. Evidence was given by Crown witnesses in several languages and dialects. The Crown’s case lasted for nearly three days and tempers mounted steadily. Biggs called as a defence witness Hon. James McKay, whom Dr. O’Donnell describes as a quasi-king among the half-breeds.

McKay knew nothing of the relevant facts of the case and the Chief Justice well knew this. He demanded to know why McKay was being called as a witness. “My Lord,” said Biggs, pretending astonishment for the benefit of the half-breed jury, “My Lord, I propose to shew by this witness that the Indians who were killed were savages, and that they fell in warfare, and that this was not murder but in self-protection.”

“Why, sir,” bellowed His Lordship, his patience now stretched to its limit, “your own ancestors were savages only two or three generations ago.”

“True, true, my Lord,” quietly replied Biggs, “I claim the same ancestry with yourself, only one generation farther removed.”

This neat reply was enjoyed by everyone in the courtroom except Chief Justice Wood, who did not have an active sense of humour. Biggs’ doubtful tactics carried the day. The jury acquitted his clients, much to the annoyance of the Chief Justice who hated to see men whom he considered guilty cheat the law.

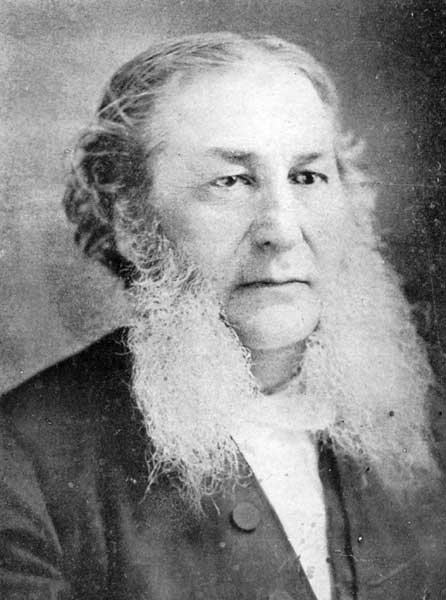

Let us climb back through history up the stream of time and take a look into Chief Justice Wood’s courtroom in the frame building at the corner of Main Street and William Avenue built in 1874, at a cost of $35,000.00, to serve as Winnipeg’s Court House, long since a casualty in the steady march of progress. He is seated in an old-fashioned, high backed mahogany chair. Queen Victoria’s picture is on the wall behind him. A large man, with the chest and shoulders of a gladiator, shrewd, penetrating eyes and luxuriant side whiskers, he is dressed in a simple black gown. He watches attentively all that is taking place before him, now jotting down a note in his court book, now interrupting or rebuking counsel, now taking over the examination or cross-examination of a witness; always alert, sometimes impatient of delay or inefficiency and making his impatience only too apparent. When he speaks, it is always with a purpose, if only to relieve his feelings. The Manitoba Free Press once spoke of his voice as: “rich, sonorous, full-toned.” These are polite adjectives, but the Manitoba Free Press had, perhaps, a similar thought in mind as had D’Arcy McGee when, in the House of Commons, he gave him the name of Big Thunder! Sometimes in his small courtroom his voice sounds like the rumble of Big Thunder. As he presides over his court, he has a certain rough dignity, but only too frequently he throws it away to indulge in a heated battle of words with counsel, or to dragoon a witness who is not giving his evidence in a manner which satisfies him. He is a dominant figure, assured and assertive, perhaps too much so to be the true embodiment of British justice.

A judge speaks and acts through his judgments. Let us then look at a few of Chief Justice Wood’s judgments.

One of the cases over which he presided in Michaelmas Term, in 1876—Fitch v. Murray—must have caused quite a stir in a small community such as Winnipeg then was. The plaintiff and his wife had been convicted in Police Court of keeping a disorderly house but on appeal the conviction had been quashed. The defendant, the Chief of Police of Winnipeg, had been the main witness for the prosecution. A few days later the defendant went to the plaintiff’s house twice on the same day. On the second occasion the defendant got into an altercation with the plaintiff’s wife over the conviction and appeal. The plaintiff ordered him to leave the house. When he refused, a fight took place. The defendant arrested the plaintiff in his own house, took him to the police station and locked him up. The plaintiff was convicted by the Magistrate of calling the Chief of Police an abusive name. On certiorari this conviction was quashed on the ground that it disclosed no offence in law. The plaintiff then sued the defendant for false imprisonment and malicious prosecution. This action came before Mr. Justice Betournay and a jury and was dismissed. Chief Justice Wood became concerned in the case when the plaintiff obtained a Rule Nisi for a new trial. This case gave the Chief Justice the opportunity of writing one of his best judgments in which he vindicated ancient principles of the common law and gave convincing proof that he had great legal ability.

After neatly stating the facts of the case and summarizing an imposing array of legal authorities, His Lordship concluded his judgment with some general observations, as pertinent today as they were eighty years ago. “The law has always been jealous of personal liberty,” he said. “The great charter declared that ‘no one shall be deprived of his liberty without due process of law.’ The Common Law has always guarded with sleepless vigilance the individual liberty of the subject, and surrounded his house with its broad shield, and declared it, however lowly, however humble, to be his castle ... If the defendant can go into the plaintiff’s house, under the plea of inspecting the house, and when requested to leave the house, answer he ‘will stay as long as he likes, and leave when he gets ready;’ that ‘he is there in his official capacity,’ and, on getting into an altercation, arrest the proprietor of the house and take him to prison for no offence whatever, and all this without any previous formal information, and without any warrant, he may do the same thing in every house in Winnipeg. No one has any security against the caprice or whim of the Chief of Police. Every hearth and home may be invaded with impunity. For the law treats all alike. It is therefore of the greatest public importance that the law, in this respect, should be well understood and speak the same language to all; that the police should know and perform its duty, and that private persons should know and perform their duty, that they should know their legal rights and be prepared to vindicate them; while, at the same time, they should be ready to yield prompt obedience to police regulations which are made for the advantage of all, and to those appointed by law to carry them out.”

Would that the Chief Justice had always maintained this high level in his judicial work!

Another case which must have aroused intense contemporary interest in Winnipeg is the case of Regina v. Rowe., which came before the Court in Trinity Term, 1880. Here the defendant was the editor of the Winnipeg Daily Times. The Chief Justice, sitting in the County Court for the County of Selkirk as a Court of Revision, gave a judgment whereby between four and five hundred names were removed, or withheld, from the voters’ list. Two editorials appeared in the defendant’s newspaper, under the captions: “A wholesale disfranchisement” and “The latest outrage.” To suggest their blunt tone, here is a passage from the second of these editorials: “Disfranchised on a petty quibble—so outrageous that one cannot conceive the law would ever permit, or a Chief Justice sanction it—strained to its utmost tension—in equity, in justice, in common decency there is not the slightest pretext, except a forced construction of the law, for such wholesale disfranchisement—the pretext given is an act that can only be designated as one of the grossest perversions of justice ever recorded—one of the greatest outrages ever perpetrated in the name of British justice—it could only be accomplished by a forced construction of the law—it is contrary to the spirit and intention of the Act; contrary to all sense of equity or decency; and calculated to tarnish the fair name of the Canadian Bench with a charge of partisanship.”

These are strong words and the writer of them was summoned before the Court to show cause why he should not be committed for contempt. Argument on this summons was heard by the Chief Justice and Mr. Justice (later Chief Justice) Dubuc who had been appointed to the Court on the death of Mr. Justice Betournay. H. M. Howell (later Chief Justice) appeared on behalf of the defendant and, in his usual vigorous style, put up a strong defence.

Chief Justice Wood wrote a judgment in which he dealt with the effect of the defendant’s conduct on the administration of justice, and defined the limits of fair comment on judicial proceedings by the press. A brief excerpt may serve to suggest its flavour:

“The press is a powerful factor in modern civilization. Its influence in correcting abuses and advancing reforms is immeasurable. But there must be limits to its latitudinarianism in its comments and imputation on character. But my present purpose is to indicate to what extent it may, according to law, go in respect of judicial proceedings; and here, I may remark, is a wide field for the exercise of its energy, with advantage to the public.

British Courts never shrink from the experimentum crucis of the most searching logic and sharpest criticism. Governed by principles and rules of decision which have their basis in natural justice, they rather invite than interdict examination. Property, reputation, liberty, and life are within their power and disposition according to law. The most insignificant and most momentous concerns of human society are subordinated to law as administered by the Courts of Justice. Justice as administered by our Courts underlies the social fabric and connects itself with the very foundations and framework of civilized society. The tribunals of Westminster Hall have been one of the most powerful factors in working out and placing upon a sure and lasting basis the great problem of human liberty; and have done more, and are now doing more in establishing, maintaining and preserving British liberty and equality over the whole world than the army and the fleets of the empire. Therefore, the calm and temperate criticism and discussion by the newspaper press of the decisions of our Courts of justice, are on all proper occasions not only to be permitted but to be invited; but mere invective and abuse, and the imputation of false, corrupt or dishonest motives to those who are engaged in the arduous duty of the administration of justice, instead of benefitting the community by the dissemination of correct information in respect of the rights of property or person, or by pointing out, and thereby being the means of correcting error, obviously tend to the destruction of all confidence in the administration of justice, and thereby sap the very foundations of the whole social system.”

This judgment leans a little heavy, perhaps, on the rhetorical style so dear to the hearts of the Victorians but, stripped of all literary flourishes, it rests on a firm foundation of good sound sense.

Mr. Justice Dubuc wrote a judgment in which he concurred with the Chief Justice. E. Douglas Armour edited a report of the case to which he added this interesting footnote: “At this time there was a vacancy in the Court, and the motion was therefore argued before two Judges only. They being unable to agree upon a penalty, no punishment was ever imposed upon the defendant.”

Sometimes Wood let the broad moral aspects of a case lure him away from the strict letter of the law. Perhaps, his tendency in this regard may best be illustrated by the case of Farmer v. Livingstone, which first came before him in the spring of 1879. Farmer claimed title to certain land under a patent from the Crown and sought to eject Livingstone who was in possession of the land under a good moral claim. Counsel for the plaintiff filed his client’s patent and rested his case. The Chief Justice allowed defendant’s counsel to give evidence of the circumstances under which Farmer was given his patent—in other words, to impeach a title granted by the Crown under its Great Seal. In a twenty-one page judgment, Chief Justice Wood held that the patent issued to the plaintiff was void as having been issued in error and mistake. Farmer appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada and, in a short judgment, this Court reversed the Manitoba Court. Farmer thus had a judgment entitling him to possession of the land. In an attempt to defeat him from recovering possession, Livingstone entered a bill in equity to restrain him from enforcing his judgment. Chief Justice Wood and Mr. Justice Betournay granted him this relief. Again Farmer went to the Supreme Court. In his judgment, Chief Justice Ritchie, Chief Justice of Canada, remarked: “The learned Chief Justice (Wood) says: `The evidence of the plaintiff discloses at least a moral wrong done him, a prejudice, a grievance.’ Now courts of law do not sit to redress moral wrongs, unless the moral is accompanied by a legal wrong, such as a court of law or equity can recognize—any mere moral wrongs invading no legal or equitable rights recognized by law must be left to be disposed of (in the forum of conscience). Before a defendant in an action at law can ask a court of equity to stay the execution on a judgment regularly and properly obtained in a court of law, he must have rights in the legal sense of that term.”

Mr. Justice Henry of the Supreme Court wrote a judgment in which he was more forthright: “By the judgment lastly appealed from, (he held) the two justices of the Queen’s Bench have, in the most marked and direct manner, undertaken to reverse the judgment of this court, and virtually made their court an appellate one from the judgment of this court deliberately and clearly given.”

But though the Supreme Court overruled him, Chief Justice Wood remained firmly of the same mind. In Boultbee v. Shore, one of the last cases upon which he sat, he remarked: “I refer to observations cognate to this subject, which I made in giving judgment in Farmer v. Livingstone ... to every word of which I still adhere notwithstanding my judgment was reversed by the Supreme Court of Canada on a technical point.”

Mr. Justice Holmes once remarked that the law is a magic mirror wherein we see reflected not only our own lives but the lives of all men that have been. In the records of the courts—where the law may be seen in action—are found the clearest reflections that the law provides of the lives of men that have been. Court records are a mirror in which may be caught glimpses of the social and political problems that vexed other days. Consider, for example, how clearly are reflected certain tensions of Manitoba’s early days in the court records of the case of The Queen v. Maxine Lepine et al, a case tried by Chief Justice Wood and a mixed jury on 4 March 1880. The charge against the accused was common assault. The facts were simple. Damase Arcand and his family lived in a room which had been built onto the home of Maxine Lepine. Lepine wanted to recover possession of this room and went about it in his own fashion. He attempted to throw Arcand’s cooking stove into the street and install his own stove. Arcand defeated him in two attempts. Finally on 1 January, assisted by two friends, who had been indulging with him in some New Year’s cheer, Lepine made a third attempt. Again he failed but in the process Arcand was given a pretty thorough beating. The three accused were defended by J. A. N. Provencher and during the trial considerable heat was generated by his clashes with Chief Justice Wood. The Chief Justice finally discharged the jury and empanelled another. After hearing the evidence, this second jury took but a few minutes to convict the accused. During the trial, the Chief Justice had suggested that the accused would have been well advised to have pleaded guilty and intimated to Provencher that it would be a waste of time for him to address the jury. In passing sentence upon the accused, the Chief Justice said:

“The circumstances that surround the trial render this case most important in a public point of view. According to the statute of offences, it is undoubtedly the right of every accused person, of French or English origin, to have half of the jury skilled in the language of the defence. For some extreme cases, that provision may have been very wisely conceived. I am not prepared to say that my experience on the bench in Manitoba has convinced me that, as a general rule, it is in the interest of the public or in the interest of the administration of justice. It is very apt to create a notion in the minds of the jury that one half are on one side, and the other half on the other. Now if anything has ever distinguished English juries it is their extreme care and impartiality in trying any foreigner for an offence; and if any criminal cases jurors are ever conciliated and yield to extenuating influences, these cases are when foreigners are put on trial before an English Court and jury.

At the last Assizes we had before this Court, a most awful crime against society, and the evidence as to the guilt of the parties was perfectly clear. But we had a mixed jury, and the scoundrels who committed the offence went unwhipt of justice. I should have done then what I did yesterday—discharged the jury immediately and empanelled another. On the first jury yesterday, the assertion was made in the jury room, by those speaking the French language, that I had directed the jury to find a verdict of Not Guilty. I happen to know this because they sent a message to me through the Sheriff, to ask whether or not that was the fact. A portion of the jury sent this message, whereupon I sent back word, through the Deputy Sheriff, along with an interpreter, that I said nothing of the kind but quite the reverse. They said that they did not care what the Judge said, nor what anybody else said, they would find a verdict of Not Guilty. The Court then had no alternative but to call on the jury, and if it was found that there was no prospect of their agreeing, discharge them. This was done. And for the future in such cases I shall pursue a similar practice. I am determined to stamp out such action on the part of juries—otherwise we might as well give up the administration of justice in this country. Jurors must know—and must be taught it if they do not know—notwithstanding what counsel may tell them to the contrary—that they must give their verdict according to the evidence that they must take the law on evidence and direction from the Court the officer presiding being responsible for the direction that he gives. I have further to mention, that the notion that there is any distinction to be made between persons of different origin in the administration of justice, must be abandoned. No person can say that in so far as this Court is concerned there has been the slightest discrimination, and I should lament to see the day when Her Majesty’s Courts in the administration of criminal justice, should know any man.”

Do not these words spoken in court by Chief Justice Wood on the hearing of a very minor case suggest something of the friction between two races of different language and religion who had not yet learnt the important lesson of tolerance—a friction soon to break forth in its full fury over the issue of separate schools in Manitoba?

William Perkins, Manitoba’s first court reporter, a born raconteur, who died in 1948, at the age of 95 years, had many a good tale to tell of the early history of the courts of this province. As might be expected, several of these stories concerned the colorful Chief Justice, in whose court he began his long career as a reporter. One such story, a perennial favourite with Perkins, whenever he was in reminiscent mood, runs as follows: One morning after he had had a rather bad night in congenial company, N. F. Hagel, one of the best criminal lawyers the West has ever known, whose favourite drink was ’an amber fluid distilled from Highland springs,’ took a little whiskey with his porridge to revive his failing spirits. He had a case before Chief Justice Wood that morning, which was important to his future at the Bar, for he had but lately come to Winnipeg from Toronto and this was an opportunity for him to show his mettle. In the interests of his health, he walked to the Court House, arriving early, before anyone was astir. As he wandered about the Court House, he went into the Chief Justice’s room and there he saw on his desk a written judgment in the case which the Chief Justice was to try that morning. Glancing at this judgment, Hagel found that it went against his client.

When Court opened at ten o’clock, the Chief Justice asked, as was the custom of the day, if any of the assembled lawyers had any motions to make.

Hagel rose to his feet with great dignity. “Yes, my Lord,” he said, “I rise to make a motion of a very serious nature. I move to impeach the Chief Justice of this Court for prejudging a case.”

“What do you mean, Mr. Hagel?” demanded the Chief Justice with a great show of indignation. “Such insolence cannot be allowed to pass. I shall have to hold you in contempt.”

“If Your Lordship will read that document which you had in your hand when you came into Court and which now lies before you, it will be apparent to all in this Court what I mean,” replied Hagel, unmoved.

Jumping to his feet and grabbing the document from his desk, Chief Justice Wood shouted “Impeach and be damned,” as he rushed from the Courtroom.

Later Hagel’s case came on for trial before the Chief Justice and a decision was given in his client’s favor.

Hon. James Emile Pierre Prendergast, Chief Justice of Manitoba for fifteen years, arrived in Winnipeg from his native Quebec in the spring of 1882, to try his fortunes at the Manitoba Bar. As he made friends among the lawyers of Winnipeg he began to hear tales of Chief Justice Wood’s arbitrary behaviour, some of which he could hardly credit. One day, when he had an idle hour to spend, he went into Chief Justice Wood’s court to satisfy a curiosity that had been aroused by these tales. It was the day before a public holiday and the Chief Justice had been celebrating prematurely. His celebrations had taken a heavy toll of his faculties. Neither mentally, nor physically, was he his usual alert self.

When Prendergast entered the courtroom, a police constable was in the witness box giving evidence for the Crown against an accused who was charged with keeping a still. As he gave his evidence in a clear, deliberate voice, the Chief Justice made notes in his court book, writing so violently that the sound of his pen, as it raced across the page, could be heard by the astonished young man from Quebec from his seat at the back of the courtroom.

“I found a stove at the accused’s farm,” said the witness.

“Found a stove at the accused farm,” repeated the Chief Justice, as he wrote in his notebook.

“And two mash cans,” added the witness.

“And two ash cans”, repeated the Chief Justice.

“Pardon me, my Lord, but I said two mash cans,” interrupted the constable.

“Yes, yes, ” said His Lordship irritably, as he glared fiercely at the witness. “You found two ash cans, I heard you the first time. Get on with the case.”

“Mash, not ash cans,” persisted the witness, determined to make himself understood.

“Don’t go on repeating yourself,” remarked His Lordship. “I heard what you said. I’ve got it down here in my book.”

Then suddenly throwing down his pen, the Chief Justice mumbled to himself, ’ash cans, ash cans.’ As if these words were registering with him for the first time, he thundered: “What nonsense have we here, trying to convict a man of keeping a still because he has a couple of ash cans on his farm. Why, there isn’t a farmer in the Province of Manitoba who hasn’t ash cans on his farm. Don’t bring such trifling stuff before me. Case dismissed.”

In telling this story, Chief Justice Prendergast remarked that after seeing Chief Justice Wood in action, he listened with a less credulous ear to his brother lawyers’ complaints about him.

Dissatisfaction with Chief Justice Wood’s arbitrary ways, which had mounted steadily through the years, came to a head before the time of which we are speaking.

On 4 March 1881, Hon. Joseph Royal presented a petition to the House of Commons setting forth various charges against him and praying that the House take the petition into its favourable consideration and deal with it in conformity with the interests of the pure administration of justice. This petition was signed by H. J. Clarke, William Boyle, F. T. Bradley, and J. E. Cooper. It contained, amongst others, the following charges:

1. That by changing the dates on certain documents and records, the Chief Justice procured the illegal outlawing of Louis Riel.

2. That he prepared a list of half-breeds who were enemies of Ambroise Lepine to serve on the jury which tried him for the murder of Thomas Scott.

3. That as a judge, he took an active part in politics, continually introducing into his charges to the grand jury contentious local and Dominion political issues.

4. That in his charge to the grand jury at the spring assizes of 1880 he declared that he had no confidence in the oath of any French native in the Province.

5. That he was in the constant habit of using the most abusive language towards both suitors and members of the bar in open court, at times displaying such uncontrollable temper and bursts of passion while on the bench as to disgust all parties who were so unfortunate as to be compelled to submit to his abuse.

6. That he made a habit of taking the un-sworn statements of persons on the streets or at his home in preference to the sworn testimony of witnesses in court.

7. That he degraded the administration of justice by gross exhibitions of intemperance while travelling on circuit.

The petition reached Ottawa too late in the session for any action to be taken that year.

Carrying the war into the enemy’s camp, Chief Justice Wood made the charges against him the subject of an address to the grand jury, in which he sought to justify his own conduct and attacked in vigorous language the character of the petitioners.

He printed his address at his own expense and distributed it far and wide throughout Canada. He also prepared in his own handwriting a voluminous answer to the charges which he sent to Ottawa.

There the matter rested until 1 May 1882, when Dr. Schultz moved the House of Commons for the reading of the Journals of the House so far as they related to the petition of Henry J. Clarke QC and others.

Hon. Edward Blake opposed this motion, counselling caution in such an important matter as an inquiry into the conduct of a judge. “Judges of this country,” he pointed out, “hold their offices during good behaviour and can only be removed on a joint address by the Senate and the House of Commons.” He urged that no action be taken until the charges against the Chief Justice and his answer had been printed and distributed among the members of the House.

In replying to Blake, Schultz pointed out that the Chief Justice’s answer embraced nineteen quires of foolscap. “Any further delay,” he suggested, “(would) lead to the conviction in the mind of Chief Justice Wood, and of other culprits like him, that all that is necessary to prolong his case or to save him from investigation is to fill an extra quire of foolscap.” After considerable debate, Schultz’s motion was adjourned. Later the House of Commons ordered a departmental investigation into the charges against Chief Justice Wood. The Chief Justice died before this investigation was completed and there the matter was allowed to rest.

On Saturday, 7 October 1882, Chief Justice Wood was engaged in his Court on a case—Gerrie v. Stanley—testing the title of the Hudson’s Bay Company to certain land in St. Boniface. Much to the annoyance of counsel, he sat late into the afternoon. Tired and irritable, he was yet determined to finish the case before rising from the Bench. Counsel finally pressed him for an adjournment and he made no reply. He was sitting slumped forward in his chair. It was some minutes before it was realized that he had been visited by an attack of paralysis which had left him unconscious. He was carried from the Court to his home and died that evening without regaining consciousness, in his sixty-third year.

Shortly before his death, he made a speech in which he struck an intimate note. “I am now aged,” he said, “grown gray in the service of my country, but not rich. I have no wordly possessions, but I have that which, in my estimation, far surpasses any such considerations—a consciousness of having, to the best of my ability, under all circumstances striven to do my duty; and my aim has been to leave behind me, not money or lands, but a pure and unsullied reputation, in my private relations with men and in my public and official capacity, and above all, my aim has been to lay the foundation and rear thereon the superstructure of a wise and pure administration of justice, and I think I have accomplished the object at which I have aimed.” Without pressing the point too far, these words may be taken as his own apology for his life.

How shall we sum up Hon. Edmund Burke Wood as a judge? Measured by the standard suggested by Lord Acton: judge talent at its best and character at its worst, he does not come off very well. He had great talent—his reported judgments put that fact beyond question. He could write a neat, rounded, well-reasoned judgment.

He was a master of clear exposition and homely illustration. Let me offer proof by quoting a line or two from several of his judgments. In Hudson’s Bay Co. v. the Attorney-General, in dealing with the province’s right to impose taxes, he said: “The imposition of taxes is one of the highest acts of sovereignty. Taxes are burdens or charges imposed by the legislative power to raise money for public purposes. The power to tax rests upon necessity, and is inherent in every sovereignty.” Could he have put the matter more clearly, or succinctly?

Dealing with the vexing problem of damages for breach of contract which are rarely an adequate compensation for injuries sustained, in Clarke v. Murray, he said: “A bottle of laudanum may save a man’s life, or a livery hire may enable a man to make his fortune in a pending transaction; but neither is paid for on this footing. The price of each is based on its market value: and this operates and becomes a liquidated estimate of the worth of the contract to both parties, and as the measure of damages in case of breach.”

In his judgments he could strike what Mr. Justice Cardozo has called the magisterial note, the note that silences all dissent: for example, in M’Kenney v. Spence, an action brought to recover possession of a parcel of land on Point Douglas, he said: “It seems the very highest equity that he who shall bona fide, in mistake of title, make permanent improvements on land, should, when the true owner takes away the land from him, be compensated to the extent that his improvements have enhanced the permanent value of the land; and in this view I am fortified not only by the reason of the thing, and a sense of natural justice, but also by the highest authority.”

Instances of his faculty for apt expression can be multiplied. Let me give one more. In his ill-fated judgment in Farmer v. Livingstone, he said: “This is a principle of law and of natural justice too plain to require any elucidation, or to be enforced by any argument. It needs only to be stated to receive the universal assent of intelligence.” The man who wrote these words had surely an intimate acquaintance with the great masters of didactic prose.

Chief Justice Wood’s industry matched his ability. He was a slave to his work, sitting in his Court, early and late, and taking great pains, and we may suspect not a little pride, over his written decisions. There was no five-day, forty-hour week for him. He had a genuine interest in his work and a reverence for the common law, which he once called the Bible of liberty and freedom. He saw a vision of what was right and just, if he did not always pursue that vision by appropriate means.

This much can be said in his favour without parting company from the truth. But there are accounts—and these are concerned with character, not talent—to cast up on the debit side of the ledger. He did not have a judicial temperament. He was short-tempered, arbitrary, impatient, opinionated. In two words, he was a judicial dictator, and the last place where a dictator belongs is in the judgment seat. This much the record clearly proves. Whether he had more serious failings is not so clear. There is plenty of smoke, but as a great English Judge, Lord Justice MacKinnon, once said, the wickedest proverb that was ever invented is, “There is no smoke without fire.”

His faults as a judge have been excused on the ground that he was the sort of tough-fibred man required by the times in which he lived, that an iron hand was needed to bring order out of chaos in Red River, that the reins of civilization had to be held tightly and firmly in a pioneer community. As Hon. Alexander Mackenzie once wrote to Hon. Alexander Morris: “He is perhaps too impulsive for a judge but that very quality is a good one in a new country where justice encounters initial difficulties not experienced in older communities.” It may well be so. But the suspicion persists that his faults as a judge were not such as to leave room for much confidence in the pure administration of the law.

What sort of man was the Chief Justice when he took off his judicial robes and left the cares of his office behind? He seems to have had a fair success in his personal relationships with his fellowmen. He was a good mixer at all social levels in a pioneer community but was at his best in the close society of his intimate friends. No lean ascetic, but a man of healthy appetites, he enjoyed good living and made no secret of it. Good food and good drink were necessary for his full enjoyment of life. But so also were good books and good talk. Widely read in English and classical literature, and an enthusiastic student of history, he was a good companion for any man who took delight in the things of the mind. He was in great demand as a public speaker. The Manitoba Free Press once said of him: “He was one of the few men in Canada to whom the public have been willing to concede the name of orator. In him public speaking was not an accomplishment, but a gift; not a labour, but an exhilaration.” High praise this, but all available evidence points to the conclusion that it was not too high.

One of his best speeches was surely the Inaugural Address he delivered, in 1879, to the Manitoba Historical and Scientific Society. Let us listen to a few words from this address. “Man in society is the maker and the subject of history (said the Chief Justice) ... There is nothing too insignificant and nothing too magnificent for history, provided it tends to the illustrations of man in his intellectual, social or moral relations. The beautiful and the repulsive, the sublime and the lowly, the genuine and the counterfeit, in mind, morals and matter in all ages may photograph under a thousand forms the diversified nature of man, and in a thousand voices speak to us of the centuries that are past.” Here is the raw material of good oratory. If the Chief Justice’s manner of speaking measured up to the matter of his speeches, (as his contemporaries assure us that it did) then he was entitled in truth to the name of orator.

At a memorial service held by the members of the Manitoba Bar, H. M. Howell QC, predicted that in the years to come Chief Justice Wood would be honoured as the father of the judicial system in Manitoba. This prediction has not come to pass. Today Wood is largely a forgotten man. Generations have arisen to whom he is virtually unknown. Even to some members of his own profession he is known today only as the subject of a portrait which hangs in the marble halls of the present Court House in Winnipeg. Unfortunately, Canadians generally have little curiosity about their past. They have never taken to heart this sound advice which Sir George Parkin tried to give them many years ago: “A young country does well to take careful note of all that is best in its past. The figures in the history may or may not be of heroic stature—the work done may or may not be on a grand scale. But it is foundational work, the significance of which grows with the lapse of time.”

As a pioneer Chief Justice, Hon. Edmund Burke Wood’s work—though it may not have been consistently on a grand scale—was foundational. Its significance should have been growing with the lapse of time since his death, and, if only for the reason that he was a pioneer in the workshop of the law, he should be accorded a permanent place in the history of Manitoba.

Page revised: 11 July 2015