MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1962-63 Season

|

A few years ago, as I was coming back in early October from a trip to Eastern Canada, I was sitting, one evening, in the observation car of the C.P.R. train, which was winding its way along the northern shore of Lake Superior, passing through Heron Bay, Nipigon and Fort William, and I was quietly enjoying the scenery as so many still do on similar trips.

Everywhere there was poetry and splendour: the sun, declining towards the horizon, bathed the scenery in a wonderfully soft light; the abrupt rocks on which we seemed suspended, the tiny valleys or mere crevices in which a small creek would send its water tumbling down in an immaculate whiteness: at our feet the red clusters of the American mountain ash, the reddening foliage of the silver maple and of its more modest neighbour, the scarlet sumac, and the green of the forest forming contrast; further to the south, as far as the eye could see, that immense sea of fresh water whose emerald color seemed to be formed of millions of gleaming diamonds; all this was an incomparable spectacle.

So much beauty often leads to a state of reverie and suddenly there seemed to appear a group of birch bark canoes gliding silently between the perpendicular shore line and the islands of red granite which were covered with various shades of green.

There were several of these canoes and in each of them six or eight men amongst bales of merchandise, paddling to the rhythm of a song of old France.

Soon they slowed down and set up for the night on a nearby bank.

I do not know if in 1727, La Verendrye and his companions - for these were the men of my vision - were alive to all the beauty of the scenery which I have just described, but I know that dreams of glorious exploits filled the mind of the future explorer.

Anyway, my vision was soon transformed and a new scene appeared. I could imagine, near the actual site of Nipigon, a log cabin covered with birch bark and, standing inside, the strong figure of La Verendrye who was questioning feverishly, through his interpreter, an Indian chief, about certain things which seemed to interest him highly.

Would you like to know the subject of their conversation? It will be an easy task, for now the poetic vision ceases and we are plunged into the reality of history as related by the discoverer himself in his Memoir of 1727-1728; the first of those which he has given concerning the project which haunted him.

In a few moments I shall give you the details. Right now, I might say that the subject of their conversation was Lake Winnipeg and the surrounding country, with the rivers emptying into it or discharging its waters, and especially the river from the West, the Saskatchewan, and the numerous cascades which precede its entry into the lake, that is the Grand Rapids and all that region.

This is also the subject of the present lecture; it is the beginning of an exciting story, that of the discovery of the West. Let us first situate this beginning.

For several centuries and even before the time of Christopher Columbus, the mind of many had been preoccupied by the search for a shorter and surer route to the treasures of the Orient. France, England, Spain, Portugal and the Italian republics vied with each other in their efforts to reach those legendary riches - a race nearly as keen as our interplanetary race to the Moon or to Venus!

When Christopher Columbus discovered America, he thought he had at last achieved that end, and having reached what he believed to be India, he called Indians the first men he saw. But soon it was realized that there was another continent to cross or sail around and another sea of unknown dimensions between this continent and the shores of Asia.

The Treaty of Utrecht, in 1713, kept the French away from Hudson Bay and from the northern passage, and the only way left was through the continent. From now on, in New France, we find the expression "Plan for the discovery of the Western Sea" and it is to the realization of this plan that the efforts of La Verendrye and his successors were applied until the end of the French Regime.

Thirty-three years after its downfall, Alexander Mackenzie will achieve that end.

In 1716, after three years of preparation, the "Plan for the discovery of the Western Sea" was ready and in 1717 a start was made on it when the Sieur Zacharie Robutel de la Noue established a fort at Kaministiquia, later Fort William. He was succeeded in 1721 by Sieur Jean Baptiste de Saint-Ours-Deschaillons and then in 1726 by Jacques Rene Gaultier de Varennes, an older brother of La Verendrye. In 1727, La Verendrye himself appears on the scene and with him begins the story of Grand Rapids and of the West.

A desire for glory and a sincere patriotism always inspired his actions. Have we not seen him fight like a lion at Malplaguet in 1709 and several other occasions? He is now ready for any difficult task. The trade in furs is also in line with his inclinations and needs. La Verendrye is an idealist, but he is also a practical man. What glory would be his if he could realize for his two motherlands, Canada and France, that centuries-old dream, the discovery of the Western Sea! And how happy he would be if he could, after spending so many years in poverty and toil, provide a decent living for his family, out of the fur trade!

As soon as he is settled at Nipigon, a post which is subordinate to Kaministiquia, where his brother is in command, and acting as second under his orders, La Verendrye wastes no time, and he starts questioning the Indian chiefs whom he meets, as to any possible routes to western seas and gathers some useful information.

Precisely, several important chiefs have recently been on warring expeditions in the direction which so deeply interests him and he learns that they have discovered a great river which might lead him a long way toward his goal. In a short time, he collects much useful information.

The next year, Jacques-Rene is busy in military expeditions and, in the autumn of 1728, he is succeeded by his brother La Verendrye, who becomes commandant of Kaministiquia-Nipigon.

Meanwhile in 1727-1728, the Sioux outpost on the Upper Mississippi was re-established so as to protect that route from attacks from the South and also to find out if a better route to the Western Sea could be found in that direction.

Father de Gonnor had been sent to that post as a missionary and had been given the task by the Governor of enquiring of such a route and of the possibility of finding it by the Missouri. Returning to Quebec during the summer of 1728 to report his findings to the Governor and for other personal reasons, he stopped at Michilimakinac as was usual to the western travellers, and there met with La Verendrye who had journeyed there from Lake Superior to transact business and to send his despatches. The two men were of the same trend of character and soon understood each other.

The explorer related to the Reverend Father his conversations with the Indian chiefs and the information which he had obtained from them, and together they drafted a lengthy brief or Memoir which begins by a letter from Father de Gonnor to the Governor written in the first person and finally signed by La Verendrye.

This is the Memoir sent to the Court of France by the Governor Beauharnois on the 3rd of November, 1728 and which is entitled - "Relation of a great river which has a flux and reflux and which flows West of Lake Superior and to the North, and which could serve for the discovery of the Western Sea - presented by Father de Gonnor, Jesuit, missionary to the Sioux, to the Marquis of Beauharnois, Governor of Canada and commanding Officer for the King, in New France."

Before going any further, let us remark that this important document, the most precious of that period, has never been published. Burpee, who knew of its existence by other documents, could never find it. (We now have a photostat of it, from the Paris Archives.)

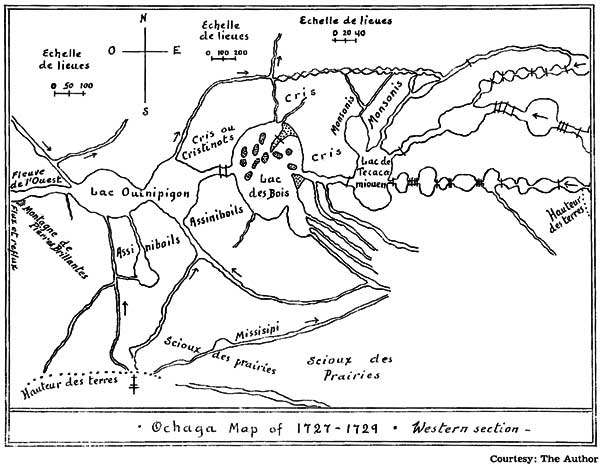

In his book entitled Journals and Letters of La Verendrye and his Sons, Burpee also failed to give us a second Memoir, written in 1729. So, we have only a third one, which accompanied a letter from Beauharnois to the Minister Maurepas dated October 19th, 1730 and which was destined to accompany the now famous map of the West by the Indian Ochaga.

This third Memoir is a summary of the other two to which he has added some new information, but is far from being as interesting and does not contain the wealth of information which is in the first. [1] Let us look at this important document of the 3rd of November, 1728.

Though the place names are not given, we can easily recognize Lake Winnipeg, the Saskatchewan River, the region of Grand Rapids and that of Lake Cumberland. Beyond that, the description is not as clear, for the information came from other Indians who had received it from still other Indians. Here is what Father de Gonnor writes, either from dictation from La Verendrye or at least from information given by him. "I was returning from the country of the Sioux where my superiors had sent me the previous year ... I had arrived at Michimakinac a few days hence and was ready to return to Quebec, disappointed at not having learned anything which could satisfy your desire and that of the Court, regarding the discovery of the Western Sea, when to my great joy and owing to the most fortuitous and happy circumstances I met Monsieur de La Verendrye who was returning from the North and who gave me to present to you his Memoirs, which he has compiled from reports made by several Indians.

"Here now is what has been communicated to me by Monsieur de La Verendrye, commandant under your orders at Lake Nipigon on the Northern side of Lake Superior.

"A man named Pako, of Indian stock, who lives near the river Camanistigoia, last year being at Lake Nipigon, told Sieur de la La Verendrye, that having gone on a war expedition he set his course towards the setting sun and after a few days reached the height of land where he found a lake which discharged in three directions, one to the North and on to the sea: it is by this river that the Cristinaux and the Assiniboals go to trade with the English who are on the Hudson Bay; the other runs South and reaches the Mississippi, the third which is the largest goes towards the setting sun... The beauty of this river beckoned my men and myself to follow it ... It is true that soon we found so many cascades and waterfalls that we would have been discouraged if after a day and a half we hadn't reached the end of these.

"What encouraged him further, said he, to continue on their route, was the fact that they did not see any more muskegs or fir forests as in their country. Only a beautiful river which grew ever wider, quite deep and bordered on each side by a beautiful sandy beach and, a little further, extensive prairies where roamed all kind of beasts, and dotted with clumps of trees bearing edible fruits. On the second day he says that they arrived at a village where they found a lot of Indians living in tents near the said river, of whom they made friends. Having stayed there a while, they continued their travel being assured that all the nations of these parts were at peace ... They passed without hindrance by several villages quite populous and descended the said river until they reached the flux and reflux, where they were so astonished by seeing the waters to rise and fall back every day that they were afraid to go further and decided to return.

"We then asked the narrator if this river was very wide where this flux and reflux occurred, to which he answered that we could hardly hear the sound of a gun from one shore to the other."

The narrator goes on with a lot of information, sometimes quite exact, at other times completely inaccurate, on the plains and on the peoples who inhabit them and beyond, and also on the nations who live by the sea.

From this point on, the information is only partially based on actual facts and having been told and retold, sometimes for several generations, had been embellished in the telling, and none of the Indians present had ever been so far.

Let us give in a few words a summary of this document which contains the first information (de visa) on the region of Grand Rapids.

Starting from Kaministiquia and going in a westerly direction with his small troop of warriors, Pako rapidly makes his way to Lake Winnipeg which he places "at the height of land" and which communicates with three important rivers. The first is the Nelson which flows to the Hudson Bay to the northwest and which the Crees and the Assiniboines sometimes follow to reach the English traders; the second is the Red River which comes from the south and has its source near the Mississippi; the third is the Saskatchewan which flows from the west.

Arriving at the mouth of this river, Pako and his men enter it. They are soon faced by a series of cascades and waterfalls which they ascend during a day and a half, being obliged to make several tiresome portages. This is the Grand Rapids and the other smaller rapids which are encountered until Cedar Lake is reached.

The warriors are tempted to turn back, but the scenery changes suddenly and offers a more inviting perspective. The firs, which tend to grow in poorer soils, have given way to other kinds of trees. The river widens into numerous lakes and beyond one can see large expanses of prairie where there are various kinds of game and many groves of trees bearing edible fruits. We here recognize the Saskatchewan River, so different from the rivers that we find in the land of the Crees, to the east and the north. They finally came to a spot where they note a sort of flux and reflux of the waters, which terrifies them so much that they decide to return home.

Let us here make a few remarks.

Firstly, it is clear that we cannot accept literally the expression "a lake having three discharges". The same should be said of the expressions "a river descending towards the setting sun" and "which was ever widening".

For the Indians, a river or a series of waterways, including lakes, portages, etc., is a route, and they have little knowledge of which way the water flows, so that it is no wonder if in "descending" the great river, they arrive at a "height" of land!

When you travel on the Trans-Canada Highway, you don't ask yourself which way the route is leading, east to west or west to east ... You are the traveller, going from Winnipeg to Montreal or from Montreal to Winnipeg. So with the Indians and their "water-routes".

As to the river which goes on "ever widening", this is an allusion to the numerous lakes through which it winds its way in that part of the country. The expression "flux and reflux" would lead us to believe that Pako relates purely imaginative facts or hearsay evidence from other Indians.

But this is precisely a most precious detail and which indicates to us the furthest point they reached: Lake Cumberland. As proof of this let us read a text of Daniel Williams Harmon, an employee of the Northwest Company, as he puts it in his journal under the date of 17th September, 1806:

"Cumberland House, September 17 (1806). [2]

"The surrounding country is very low and level, so that, at some seasons, much of it is overflowed. This accounts for the periodical influx and reflux of the water, between this lake and the Sisiskatchwin (Saskatchewan) River, which are distant six miles."

And further on we note the following text:

"Cumberland House, April 6 (1807).

"The ice in the Sisiscachwin River is broke up, and the great quantity of snow that lately has been dissolved has caused that river to rise so high as to give another course to a small river of nearly six miles long, which generally takes its waters out of this lake, whereas it now runs into it."

Harmon, in his journal, mentions several times, as does La Verendrye, this unusual phenomenon, which was of such nature as to be noticed by the Indians and their white brothers as well and which had so scared Pako and his men.

Alexander Mackenzie, it is true, mentions a similar and better known occurrence, which results from the proximity of the Peace River to Lake Athabasca; his text clearly indicates that Pako did not go as far west. [3]

It is quite evident that the story of the Indian Chief Pako and that of Harmon relate the one and same phenomenon and that Pako had reached Cumberland Lake and went no further.

This is also confirmed by the fact that both the Journal of 1728 and Ochaga's map indicate the end of Pako's expedition as being 200 leagues further than Lake Winnipeg.

Actually, there are not more than 220 or 225 miles from Lake Winnipeg to Lake Cumberland, but if we take into account the ordinary exaggerations of the Indians and the difficulties and surprises encountered on this first trip in a new territory, we have no reasons to wonder about the measurements given in the texts as well as on the various copies of Ochaga's map.

As to the width which the Indian chief gives of the river where he noticed the flux and reflux, suffice it to remember that the Saskatchewan River divides itself into several branches at this point and that the main part of the stream loses itself into the southern end of Cumberland Lake. Note also that this region could have been partially inundated and the river could form several lakes of varying dimensions.

The rest of the Memoir refers mainly to the vast prairies of the Southwest, which lead to the Mandans of the Missouri and even to the Spaniards of New Mexico.

La Verendrye knew that we must not add too much credence to the highly colored stories of the Indians and he would not have liked to be taken for a dupe, but the agreement of these narratives struck him and he was led to believe in their veracity.

He is careful to warn us of all this. "It is not", he adds, "that we must always believe the Indians who, having little to do and not knowing how to while away the time, spin these yarns which they tell and retell as being of the utmost veracity and that, with the greatest effrontery.

"We listen to them, never saying no, for we would be despised if we did and would lead them to believe that we are witless, but we do not always believe them for all that.

"Sometimes we are right and sometimes we are wrong on such occasions, because the Indians, even the greatest liars among them, sometimes tell the truth. Now, it would seem that this is one instance where we cannot suspect them of inducing us in error without being taxed of excessive incredulity or utter blindness." [4]

And then the future discoverer gives his reasons for accepting what Pako and others had told him, namely, that all reports received from these Indians were identical on the essential facts, as the existence of a great river and of a kind of flux and reflux, and that several of the Indians have spoken without being influenced in any way and even without being questioned.

Finally, the explorer, at the end of his Memoir and before signing it, declares that he is ready to swear under oath as to the veracity of his affirmations.

Equipped with this information and a few more notions which are mentioned in the two other Memoirs, that of 1729 and that of 1730, as well as with a remarkable map drawn with charcoal on a piece of birch bark by Ochaga, Tachigis and other Indians, La Verendrye begins in 1731 his slow but steady progression towards the Western Sea.

That very year, he establishes Fort Saint Pierre to the west of Lake La Pluie (Rainy Lake).

Fort Saint Charles is built in 1732 in the western section of the Lake of the Woods: for many years this will be his headquarters. In 1734 and even before, the Crees from Lake Winnipeg insist that he should establish a fort in their territory. [5] Due to the lack of funds and to the unreal and harsh conditions of the Eastern merchants, he must content himself with promises to the Crees and a compromise which will satisfy both the Crecs and the Assiniboines for the moment; he builds Fort Maurepas, No. 1 during the summer and autumn of 1734 on the west side of the Red River, approximately six miles to the north of the present town of Selkirk. This spot was on Cree territory, but was frequented by both nations.

Two Frenchmen sent in the Spring to choose a site for the fort make an inspection tour as far as the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. This is very clearly marked on the 1734 maps, of which two different copies are in existence.

These are the first white men to set foot where stands today the City of Winnipeg. This is a date to remember: Spring of 1734. They also visited the southern part of Lake Winnipeg as far as the Narrows of Tete-de-Boeuf or Bullhead. [*]

On the 15th of October, 1736, at Fort St. Charles, Lake of the Woods, the Crees from the Lake Winnipeg region remind the Discoverer of the promises he made in 1734 of establishing a fort at the lower end of Lake Ouinipigon or Lake Winnipeg. On the 4th and 5th of March, 1737, at Fort Maurepas on the Red River, the same Crees remind him again of his promise.

Consequently, in the Spring of 1737, La Verendrye sends his youngest son, the Chevalier Louis Joseph, to explore the northern part of Lake Winnipeg. But an epidemic of smallpox strikes at the Crees and a large number of them succumb, in large part those that La Verendrye had met at Fort Maurepas and Fort Saint Charles. Those who accompany the Chevalier are spared, thanks mostly to his good advice and hygienic measures, thereby heightening their trust in the French. Anyway, Louis Joseph has to return to his father who was now stationed at Fort Saint Charles, without completing his expedition. [6]

On the 16th of April, 1739, La Verendrye, having returned from his expedition to the Mandans and being stationed at Fort La Reine (Portage la Prairie), sends the Chevalier to continue the exploration started in 1737. He orders him to visit the northern part of Lake Winnipeg and the lower reaches of the Saskatchewan which he calls "White River" due to its foaming rapids, and to find a convenient place to establish a fort. [7]

Louis Joseph La Verendrye ascends the river beyond Cedar Lake "Up to the fork where every Spring the Cristinaux (Crees) of the Mountains, those of the Prairies and those of the Rivers (three different bands of this nation) meet to decide on what they will do, to trade either with the French or with the English. There he was in the Spring, assisting at the meeting of all the Cristinaux." [8]

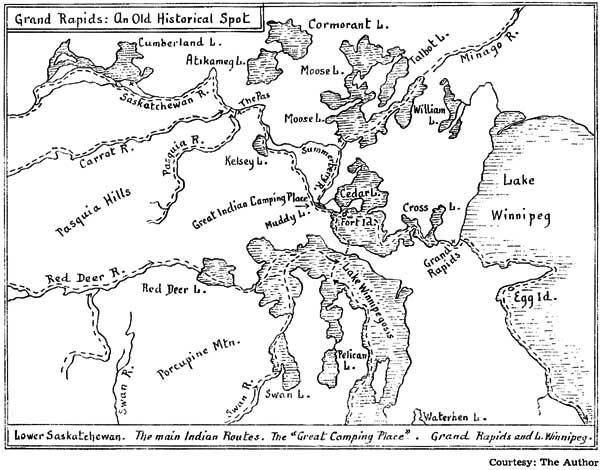

How far did the Chevalier go? - "Until he reached the fork..." says the memoir. We can believe that it is the first fork he encountered, that is, where the Summerberry River meets again with the Saskatchewan, just a few miles to the west of Cedar Lake and near the head of the delta of the Saskatchewan.

Near that point, on a little island in Cedar Lake, were constructed a little later, the first Fort Paskoya and then the second Fort Bourbon, thirty leagues from Lake Winnipeg, as told by La Verendrye in his Memoir dated 1749.

There, effectively, near the above-mentioned "fork" and according to several authors of later times, was an important meeting place of the Crees, on a limestone plateau which Henry Youle Hind indicates on his map of 1858 in the following terms: "Limestone exposed. Great Indian Camping Place. - At this spot meet the various Indian routes, one coming from the South-West (the French Forts), a second from the North-West (the English Forts on Hudson Bay), a third one from the West (the Crees and other Indians of the Saskatchewan), and lastly a fourth from the South-West (the Crees and Assiniboines) who also served as intermediaries with the Mandans, the Gros-Ventres or Big Bellies, also called Hidatsa, and possibly others."

This is then, the first historical mention of a visit by a white man to the Grand Rapids and along the Saskatchewan as far as Cedar Lake and possibly a little further.

We must, however, note that Kelsey in 1690-92 could have stopped at Cedar Lake or at the camping place aforementioned, giving to it the name of Deering's Point; but coming from York Factory, in the northeast, he most probably followed the easier and more frequented route, by the Hayes, Nelson and Minago Rivers and by one of the branches of the Summerberry, after passing through Lac d'Orignal, now Moose Lake. Description of this route is given by Lafrance, in 1742; Henday, in 1754-1755; Pink, in 1766-1768; Cocking, in 1772; and others.

But we have no indication in Kelsey, either of Lake Winnipeg or of Grand Rapids, which seems to be significant. On this point, A.S. Morton and practically all the authors agree. [9]

The Chevalier Louis Joseph, having attended the council of the Crees, descended the river and returned to Fort La Reine, having explored the contours of Lake Winnipeg on his return trip.

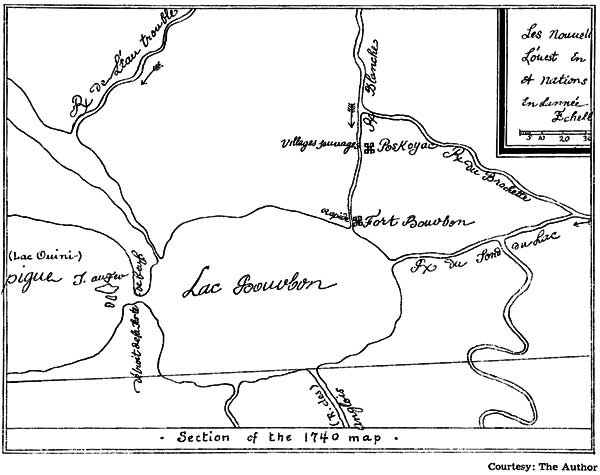

He made his report and suggested, as can be seen on the map of 1740, the erection of Fort Bourbon, between the Grand Rapids and Lake Winnipeg. He suggested also, further up the river, near one or more Indian villages, at a place called Paskoya, the erection of a second fort; or possibly this one could be indicated as a second alternative if it should prove to be the best spot; the spot indicated on the map seems to be the meeting place of the Indians. It is possible that La Verendrye himself, after the return of his son, may have visited the region during the summer as he had expressed the wish in his brief dated 1739, but he does not mention this anywhere and this does not seem probable as he was short of trade goods and one would not visit the Indians empty-handed.

The map of 1740 indicates the route taken by the Chevalier from Fort La Reine and back and the various projects which he realized on this occasion. The Chevalier follows the most direct course to Lake Winnipeg, and a location for a future Fort Dauphin does not seem to have been examined on this expedition, though such an eventuality was considered before his departure and though he may have received information to this effect from the Indians.

In all probability, the route can be indicated as follows: Fort La Reine, at Portage la Prairie, then Lake Manitoba, of which he follows the western shore until he reaches the Narrows, then the northern part of the same lake, which he crosses without examining the complicated shore line, then the Dauphin River, including the Fairford River and Lake St. Martin, then Lake Winnipeg where he follows the western shore, and finally the Saskatchewan River and Grand Rapids up to the fork of the Summer berry, a little west of Cedar Lake.

On his way back, he retraces his steps until he reaches Lake Winnipeg, where he explores the northern shore of the lake, then he follows the eastern shore until he reaches the detroit of Tete-de-Boeuf (Bullhead), having bypassed the discharge of the lake into the Nelson River, and he finally comes back to the south of the lake and by the Red and the Assiniboine Rivers he returns to his point of departure. Such were his father's orders.

We can see on the map that the northern part of Lake Winnipeg or Ouinipigon is called Lake Bourbon by the Discoverer. Then later, after La Verendrye, the name Lake Bourbon will be given to Cedar Lake, when the first Fort Bourbon is abandoned and a fort of the same name is built on that lake.

The northern part of Lake Winnipeg then reverts to its earlier name of Lake Ouinipigon (we can see this by comparing the maps of 1733 and 1734 and those of 1737 and 1740, and the ones that follow).

On the map of 1740, Fort Bourbon is only in the planning stage, as La Verendrye does not have the necessary trade goods for this establishment. He goes back to Eastern Canada at the instances of the Indians, is successful in obtaining merchandise and returns in 1741.

During this absence or possibly in 1739-1740, the Discoverer had a new Fort Maurenas built at the mouth of the Winninea River.

Passing this spot on his return trip from Montreal in 1741, he sends some of his men to build the first Fort Bourbon at the site indicated on the map of 1740, that is, between the Grand Rapids and Lake Winnipeg, on the northern shore of the Saskatchewan or White River.

La Verendrye does not have his sons with him at this particular time. The Chevalier is in charge of Fort Saint Charles in the Lake of the Woods and Pierre has left in the Spring for an expedition beyond the Mandans territory. Francois, who is not as resourceful as the others, is rarely given important tasks.

The builder of Fort Bourbon is most probably Philippe Leduc, a clerk, or maybe a partner of La Verendrye in this region. Between the 17th of April and the 25th of May, 1742, in Montreal, Pierre Gamelin-Maugras, acting as proxy for both parties, hires a group of men for Philippe Leduc at Fort Bourbon and for La Verendrye at Fort La Reine. These contracts, which are kept in the ancient files of Claude Porlier, a public notary in Montreal, give the names of twelve of the engaged men for Fort Bourbon during that period. [10]

In 1742, La Verendrye decides to build a fort at the site chosen by the Chevalier, at Cedar Lake, as shown on the map of 1740. It was erected probably during the following Winter. This is the first Fort Paskoya, situated on a small island, probably Fort Island of our modern maps, west of Cedar Lake, not far from an Indian village and towards the discharge of the Saskatchewan River into that lake.

This fort was, as La Verendrye mentions in his Memoir of 1749, thirty leagues further than Fort Bourbon. [11] We believe that the indication "Indian village" corresponds with the "great camping place" of the HindFleming map of 1858.

It is there, at the crossroad of the Indian trails, that the Chevalier de La Verendrye had been present, in the Spring of 1739, at the annual grand council of the Crees of three different regions.

Further to this decision of establishing Fort Paskoyac, Pierre Gamelin Maugras of Montreal, proceeds to a new series of engagements or contracts for Philippe Leduc at the Post of Paskoyac. We can trace thirteen of them between the 4th of May and the 20th of June, 1743. [12]

On the contrary, we do not find any for Fort Bourbon for that year which would lead us to believe that it was abandoned temporarily, for a trial period.

At this time and probably since the return of his son Pierre from the Mandans in 1741, La Verendrye had acquired the certainty, although, since at least 1737, he firmly believed, that the Saskatchewan River was the real route to the Western Sea.

The building of Paskoyac at Cedar Lake in 1743 would appear as a good step in that direction.

However, the name of this Fort Paskoya does not reappear in the documents as being actually used, which would lead us to believe that Fort Bourbon was again put into operation and that Paskoya was abandoned or reduced to a state of dependance on Fort Bourbon. This supposition seems well-founded, because during the year 1744, the engagements are signed for "Fort Bourbon and dependencies".

The resignation of La Verendrye and his return to Eastern Canada in 1744 were undoubtedly the principal reasons for these changes, which constituted a setback.

In 1749, the "Memoire abrege de la Carte," or Memoir explaining a map, apparently dictated by La Verendrye, says that Paskoya was abandoned due to a "shortage of supplies for the Winter".

There is a very plausible reason for this, for during that time the war of the Succession d'Autriche (King George's War) from 1744 to 1748 practically sounded the death knell of this vast enterprise in the West.

In the Fall of 1749, Fort Bourbon is still in its original location, on the river "Aubiche" writes La Verendrye in his letter of the 17th September and his "Memoire abrege de la Carte ..." As suggested by Father P. Picton, of Saint Boniface, Man., the word "Aubiche" is undoubtedly a corruption of the Cree word "wabish" which means "white." La Verendrye meant to say the "White River" or Saskatchewan River.

But the cartographer, who had misunderstood La Verendrye when he says that Fort Paskoya is on the river and situated thirty leagues from Fort Bourbon, invented a river "Aux Biches" (which has never existed) and he places Fort Bourbon on it. The English map makers translated "Aux Biches" to Red Deer River.

This misunderstanding of the French cartographer has led to a whole series of errors and confusions on the part of historians, both French and English and also of modern authors, following more ancient ones, who, due to the similarity of names, have placed a Fort Bourbon at the mouth of the Red Deer River, which flows to the northwest of Lake Winnipegosis, which is quite contrary to the evidence of all the texts and maps. Yet, as early as 1755, the French cartographer, N. Bellin, has corrected this error on one of his maps. On this interesting document, the false "Riviere aux Biches" has disappeared and the Saskatchewan is called "Riviere aux Biches ou Riviere Blanche"; Fort Bourbon; being where the river discharges its waters into Lake Winnipeg, was called "lac Ouinipigue ou Ouinipigon".

In the Fall of 1750, Jacques le Gardeur de Saint Pierre, having been made commandant after the death of La Verendrye and being at his headquarters at Fort La Reine, despatches Joseph Claude Boucher de Niverville to the Saskatchewan or Paskoya River, with orders to prepare for the discovery of the Western Sea, which he, Saint Pierre, was to undertake the next Spring. Niverville tried to go by canoe, by Lakes Manitoba and Winnipegosis and Mossy Portage, but was surprised by Winter and made most of the trip on sleighs hastily made, enduring enormous fatigue and privation, and, as a result, he was seriously ill all Winter and most of the following year.

In spite of all these rebuffs, he is able to construct a new Fort Bourbon, on the probable site of the first Fort Paskoya, to the west of Cedar Lake, in 1750.

This we learn from Alexander Henry (senior) who arrived there on the 4th of October, 1775. On this occasion, Henry seems to mistake the Sieur de Saint Pierre with the discoverer La Verendrye who was also called Pierre, but we cannot doubt that he refers to Le Gardeur de St.Pierre, who was commanding officer to the Chevalier de Niverville. This is clear enough when we consider that Fort Bourbon was still on Lake Winnipeg when La Verendrye died in December, 1749.

This is also the interpretation of Henry's text as given by Mr. Clifford Wilson, former editor of the Beaver magazine. [13]

It is in this new fort that Niverville spent the winter. Near the end of May, 1750, on the 29th to be exact, Niverville, being too sick to accomplish personally his mission, despatches ten of his men further up the river, possibly to Pemmican Point or to Lower Nipawi, to prepare a stock of provisions for the great expedition to be undertaken personally by the Sieur de St. Pierre. The new post built received the name of Fort La Jonquiere. [14]

It is when the second Fort Bourbon was built at Cedar Lake that this lake received the name of Lake Bourbon and that the northern part of Lake Winnipeg reverted to its ancient name, Lake Ouinipigon.

Not long after, sometime around 1751-1753, on the orders maybe of the Sieur de St. Pierre or more probably of the Chevalier Louis Francois de Lacorne, his successor, a new Fort Paskoya was built where stands today the town of The Pas; but the French already had been enaged in the fur trade for several years in that region, operating from their bases, the first and the second Fort Bourbon.

Then Lacorne pushed further than Fort La Jonquiere and built a little lower than the forks of the two Saskatchewans, a new establishment which bore the name of Fort des Prairies or Fort Saint Louis and possibly also that of Fort Lacorne, a name re-established in 1846 by the Hudson's Bay Co.

Here we come to the case of a very curious letter dated from the "Saut au Pas" on the 8th of July, 1754 and signed by Jean Baptiste Proux (Proulx) which bears evidence of certain activities at Grand Rapids even after the abandonment of Fort Bourbon in 1750. Writing to the Governor of York Factory, by the intermediary of the Indians, he asks for several things which he is in need of, namely: "a pair of lined shoes, three fathoms of tobacco, a violin with spare strings and 4 nice tin boxes," which, I suppose, would keep his tobacco fresh and clean. [15]

When this letter was written, the Chevalier de Lacorne was in command in the West. [16] Was Proulx a free-trader who also engaged in a little smuggling or was he acting with the complacency of his superior, which would lead us to believe that there were cordial relations between the then-opposing forces, French and English? This latter supposition is not only probable but certain; for effectively, at that particular time, Henday would peacefully wend his way up the Saskatchewan, stopping without ado at the French fort at Paskoya and the following year at Fort Saint Louis. But this Proulx ignored, because Henday, like Kelsey, Lafrance and others, bypassed Grand Rapids, where we believe Proulx was stationed. As to the hypothesis that "Sault au Pas," - which means Rapids or Fall of the Paskoya, - is Grand Rapids, we can say that it is highly probable, because that expression cannot be applied to The Pas or to that region as there are no rapids or waterfalls to be found there.

As to the relations between the French and the English in the West, this would be nothing new if we are to believe the records of the Hudson's Bay Co., which inform us that there was indirect trade, through the intermediary of the Indians, between the men of De Noyelles or others of that period and their English competitors, especially for heavy merchandise which the French could only transport overland with great hardship and difficulties. This was in 1746 or a little before that time.

In 1760, at the end of the French regime, the voyageur, Joseph Derouen, (Drouin) describes his voyage from the East to the West; describing briefly the area around Lake Winnipeg:

"18 leagues from Ile aux Oeufs (Egg Island, in Lake Winnipeg), to the riviere aux rapides (Saskatchewan River and Grand Rapids) ; half a league of portage; 6 leagues of river; Lake Bourbon, of 18 leagues; 40 leagues of river; at the end of which is Fort du Pas, where there are Assiniboels, Crees, etc.; 112 leagues of river to reach Fort des Prairies, which is the furthest French fort in the West, where there are GrosVentres (Big Bellies), the tribe of the river du Castor, the Crees, Assiniboels, etc." [17]

There is no mention in this text of establishments at Grand Rapids or at Cedar Lake. The Pas was already the capital of that region.

The French establishment at Grand Rapids, the first Fort Bourbon, had lasted nine years, from 1741 to 1750, maybe passing to secondary importance in 1743-1744.

Of the two establishments at Cedar Lake, the first Fort Paskoya seems to have been fully utilized for one year only, 1743-1744, and the second Fort Bourbon lasted from 1750 to 1758 when it was pillaged and burned by the Indians, due to the Franco-British war. It was not rebuilt.

Erected in 1751-1753, although the locality was frequented before that date, the Fort Paskoya-Le Pas or The Pas was abandoned in 1759, also due to the war. In 1760, it was still in existence but not in actual use by its old masters.

The Fort Saint Louis or des Prairies or Lacorne, had equally disappeared in 1757.

Between the years 1760 and 1767, none of the French establishments on the Saskatchewan were in operation and this part of our Western Country between Grand Rapids and the forks of the two Saskatchewans was travelled only by the Indians, as before 1741, and by a few voyageurs who had decided to follow their mode of life rather than submit to a new allegiance in Canada.

Now and then, however, these territories were visited by employees of the Hudson's Bay Co. and by independent traders from Michilimackinac. And that's all.

But then in 1767, life begins anew with the arrival of Canadians from the East, both English and French, and Grand Rapids hears again the old familiar voices and those of the new masters of the country.

Firstly, come the free-traders, then we witness the operations of the large fur trading companies and their fratricidal struggle whilst the great discoverers bravely make their way to the Arctic Ocean, then to the passes of the Rockies and finally reach the Pacific Ocean, that famous goal, the Western Sea.

Grand Rapids was a witness to all these events. It saw the glorious cavalcade of the past and it also saw civilization implant itself little by little in the region.

Thus the history of the region goes on, until a last achievement takes place: that of the gigantic enterprise which we are witnessing today.

We have arrived, with the abandonment of the West by the French, in 1760, to the limit we had set ourselves in this historical survey.

We have limited ourselves to this period because it is that of the beginning of the history of the West and because it is relatively unknown. We have also chosen this particular period because it was the centre of the efforts to attain the Western Sea and because the importance of the work now being undertaken there seemed an invitation to study the region anew.

1. (A) The Memoir of 1728 entitled: Relation of a great river ..., is found at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, New Acquisitions, vol. 9286, page 65 (127), etc. (B) The second Memoir, Oct. 25, 1729, entitled: Suite of Memoir of Sieur de la Verendrye sent last year by Father Desgonore (de Gonnor) . . , etc., is found at the Archives du Ministere des Colonies, at Paris, at the Depot des Fortifications des Colonies, carton 5, no. 296. (C) The third memoir is entitled: (Second) suite of the memoir of Sieur de la Verendrye, touching upon the discovery of the Western Sea. It is found at the Archives Nationales, Paris, in the collection Moreau de Saint-Mery, vol. 9, F 11, fol. 304, and is accompanied by a letter from Beauharnois, dated Oct. 10, 1730, which is found at the Archives Nationales, in Paris, series C 11 A, vol. 52, fol. 160, entitled, Seconde suite ... This memoir was published by Burpee: Journals and Letters ... p. 43 ... , etc. ...

2. A Journal of Voyages ... (1903 edition) and Sixteen Years in the Indian Country: The Journal of D. W. Harmon ..., (1957 edition).

3. Mackenzie's Voyages ..., 1927 edition, pp. 136, 240.

4. Memoir or Journal of 1728. See Note 1.

5. Journal of La Verendrye, 1734. Archives du Ministere des Affaires etrangeres, Paris. Amerique. Memoires et documents ... , vol. 8, fol. 46 and following.

* Indicated on the Chaussegros map of 1734.

6. Journal of La Verendrye, 1737, Archives Nationales, Paris, Collection Moreau de Saint-Mery, Canada 1732-1740, vol. 10 F. 12, fol. 248.

7. Journal of La Verendrye, 1739, entitled, Journal in the form of a letter, from July 20th 1738-until May 1739, to the Marquis of Beauharnois ... , etc. Original in the Canadian Archives, Ottawa.

8. Memoir entitled: Abridged explanation of the map which represents the establishment and discoveries made by the Sieur de la Verendrye and his sons. The reference to that Memoir in the Archives is unknown, but the text has been published by Margry in his: Decouvertes et etablissements des Francais ..., etc., vol. 6, p. 616, etc., and in Burpee: Journals ... p. 483, etc. This Memoir accompanied an autographed letter of La Verendrye to the Minister, dated Sept. 17, 1749, which is in the Archives Nationales, Paris, series C 11 E, vol. 16, p. 303.

9. A. S. Morton, A History of the Canadian West, p. 111.

10. Names of the engages (hired men) for Fort Bourbon in 1752: Antoine Lafranchise, Louis Major, Francois Millet, Pierre Vallee, Louis Fort (Faure), Antoine Traversy, Ignace Cournoyer, Jean-Baptiste Ducharme, Jean-Baptiste Lepage dit Roy, Francois Sauvage, Mathurin Laroche, Jean-Baptiste Forville dit Papineau.

11. We have proof that the French league in use in Canada was equivalent to 3.05 miles, but the voyageurs used to estimate it at 2½ miles or even at 2 miles to the league. In reality, there is approximately 60 miles distance between Lake Winnipeg and the presumed location of the first Fort Paskoya.

12. Names of the engages (hired men) for Fort Paskoya in 1743: Jean Cuisson (Cusson), Jacques Antaya, Francois Primot, Louis Ranger dit Gascon, Jean Laurent dit Latouche, Francois Harel, Andre Primot, Andre Lamalice, JeanBaptiste Senet, Pierre Lamarine, Jacques Harel, Jacques Lavallee, Nicolas Loysel (Loisel).

13. Refer to article entitled: "La Verendrye Reaches the Saskatchewan," in Canadian Historical Review, March 1952, pp. 39-49.

14. It would seem opportune to scratch forever the ridiculous legend which situates Fort La Jonquiere at the foot of the Rockies near where now stands the City of Calgary. Even ignoring the impossibility that Niverville's men had advanced so far and the contradictions which this would bring in the Journal of the Sieur de Saint-Pierre, dated 1753, the location is contra-indicated by a multitude of references, namely, Bougainville in 1757, Joseph Derouen (Drouin), 1760, Sir Guy Carleton, 1768, after the testimony of the French in 1754, Peter Pond, 1775-1735, Alexander Mackenzie, 1789-1801, Daniel Williams Harmon, 1804, Duncan McGillivray, 1808, Gabriel Franchere, 1814-1820, to whose testimony could be added many others who are less explicit. The French before the cession of Canada never went further West than the forks of the two Saskatchewans.

15. Original in the Archives de the Hudson's Bay Co., in London. Page or classification No. 171. Photostat in the Archives of the Societe Historique de Saint-Boniface, Manitoba.

16. This does not refer to Luc Lacorne dit Saint-Luc, as most authors persist in calling him, but to Louis Francois, one of his brothers. At this period, 1754, Lacorne Saint-Luc was a military officer in Montreal, and held a license for the post of Chagousmigon, which was administered by the Chevalier de La Verendrye as commandant.

17. Extract from "Gazettes" of Father Pierre Potier, Jesuit. Manuscript kept in the Archives of the College Sainte-Marie, in Montreal. Photostat in Public Archives of Canada. The manuscript bears the title of "Voyage de Montreal ... a la Mer de l'Ouest," par Joseph Derouen, Dec. 25th, 1760.

Page revised: 22 May 2010