Manitoba Pageant, Spring 1977, Volume 22, Number 3

|

During its more than one hundred year history, the City of Winnipeg has had only three different buildings serve as city hall. The most famous of these, the Victorian “gingerbread” structure completed in 1886, stood for more than seventy-five years. Compared to the longevity of this building, Winnipeg’s first city hall had a very short life, serving only during the years 1876-1883. Yet, was it not for a severe recession which struck in 1913, Winnipeg’s second city hall would have been replaced by a third building designed as a result of a world wide architect’s competition. Instead, the great Victorian city hall survived into the early 1960s when it was finally demolished to make way for the Winnipeg Civic Centre which today serves as the city’s municipal focal point.

In the two years following Winnipeg’s incorporation as a city in November 1873, city council meetings were held in a variety of buildings in the young city, including a furniture store. [1] By August, 1875, however, Winnipeg’s first city hall had been begun amid great ceremony. On 17 August 1875 a “grand civic holiday” celebrating the placing of the cornerstone of Winnipeg’s first city hall occurred. The ceremony began with a large procession down Main Street and concluded with the ritual of laying the cornerstone.

In what must have been the largest iron casket ever entombed in a corner-stone were samples of money, all the way from early Hudson’s Bay Company pounds and shillings to Canadian currency, British money, even Russian kopeks and Prussian coins brought in by Mennonite immigrants. There were photos galore, including the mayor and council, street scenes, dog trains, oxcarts, even Louis Riel and his rebel government; newspapers, copies of charters, bylaws and progress reports; the prize list of the first annual show in 1874 of the Industrial and Agricultural Society of Manitoba; a copy of the city’s charter of incorporation and its “rules and regulations” for 1875. [2]

Winnipeg’s first city hall, constructed at a cost of almost $40,000, [3] was formally opened in March 1876 with a concert in aid of the Winnipeg General Hospital. [4] During these early years, when the city hall was one of only a very few substantial buildings in the young city, the municipal hall was a “multi-use” building. In September 1876, for example, a group used the council chambers to organize Winnipeg’s first philharmonic society. [5]

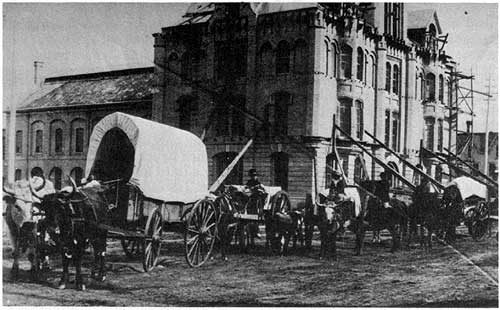

Almost from the outset, however, this first city hall proved to be structurally unsound. It had been built over Brown’s Creek, which crossed Main Street near William Avenue. [6] The land fill on which the structure was erected could not support the building and as early as 1876 ominous cracks began to appear as the city hall slowly settled into the creek bed on which it had been built. During the winter of 1882-1883 an addition was made to the city hall but it too was soon in difficulty. The addition had been constructed during the “excessive cold weather of that winter” and when spring arrived “the building showed unmistakable signs of being unsafe. Huge cracks appeared in the walls, an arch fell down, the woodwork became warped, and so many hasty signs of construction were apparent that the building was propped up for several weeks and ultimately pulled down” in April 1883. [7]

Shoring-up Winnipeg’s City Hall, 1883.

Source: Archives of Manitoba.

The first advertisements calling for plans and specifications for the erection of Winnipeg’s second city hall appeared in the city’s daily papers of Saturday, 16 June 1883. A year later, in July 1884, the cornerstone was laid. But unlike the first city hall, where difficulties occurred only after the building was completed, the second city hall was surrounded with controversy from the beginning. The first problem had to do with the location of the structure; obviously it could not be built on the same spot as its predecessor because of foundation problems. But this initial problem was only one of many. Disputes over the material used in the construction of the building and over fees paid to the architectural firm of Barber and Barber raged throughout 1884 and 1885. Indeed, the circumstances surrounding the construction of Winnipeg’s second city hall even drove one disgruntled citizen, George B. Brooks, to write a pamphlet entitled Plain Facts About the New City Hall: Its Inside History From the First Down to the Present - Interesting Disclosures. Other “pamphleteers” also commented on the “sensational” facts surrounding the construction of the city hall. [8]

Yet out of this turmoil there finally emerged in 1886 a substantial and solid structure that was to last until the 1960s when it was demolished. Winnipeg’s second city hall was a “Victorian fantasy” that captured in layers of stone and brick more than any other building of the time the exuberance and optimism of the period. [9] The new building, with its turrets and picturesque clock, embodied the spirit of the times.

Like its predecessor, the great Victorian city hall quickly became a focal point for Winnipeg. It not only served the needs of municipal government, it also provided a home in the years immediately following its construction for the Board of Trade, the library and reading room of the Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba and the club rooms of the St. George’s and St. Andrew’s Societies. [10]

Winnipeg’s second City Hall 1886-1962 (photographed in 1900)

Source: Archives of Manitoba.

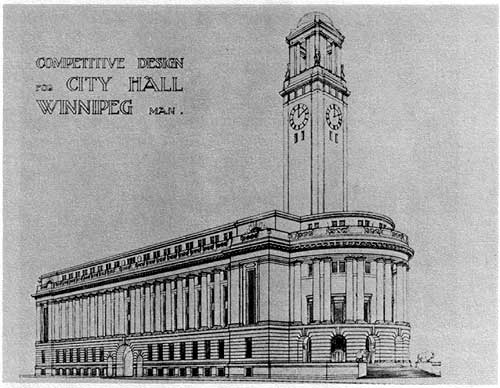

Winning design for new City Hall in Winnipeg, 1913

Source: Archives of Manitoba.

During the first decade of the twentieth century Winnipeg grew at a fantastic pace. When the second city hall was completed in 1886, the city’s population was only 20,238. By 1901 it had doubled to 42,340, and by 1911 it had soared to 136,035. [11] As a result of this phenomenal growth, city hall rapidly became overcrowded and ill-suited to the needs of the rapidly expanding civic bureaucracy. Moreover, this was a period when ideas of “civic grandeur” were widespread in North America. [12] These ideas usually expressed them-selves in advocacy of grandiose public buildings; buildings meant to serve two purposes. First, a grand civic centre would introduce beauty into the city. Second, and perhaps more important, those who sympathized with civic centre proposals wished to instill civic pride. It was, after all, a period when there was “a tendency to look on architecture as a means of communicating ideas, to choose architectural forms for their symbolic implications ...” [13]

Like other cities, Winnipeg was affected by the ideas of the period. [14] A committee of Winnipeg’s City Planning Commission recommended in January 1913 that a new civic centre be built. [15] City council responded by holding a contest for a design for a new city hall. Thirty-nine designs were submitted in competition and on 10 March 1913, Winnipeg city council announced the winner. The winning design was by the firm of Clemesha and Portnall of Regina. Second prize went to the firm Woodman and Carey of Winnipeg, and three third prizes were awarded. [16]

The style of the building was “Greek Ionic”, and the structure was to be six stories in height. It was to be built of grey Kenora granite and the estimated cost was $2,392,926.

Had the plans calling for a new city hall been completed only a year or two earlier, there is little doubt that the structure would have been built. But by the fall of 1913, Winnipeg and, indeed, all Canada was deep in the midst of a severe recession. It was soon followed by a world war.

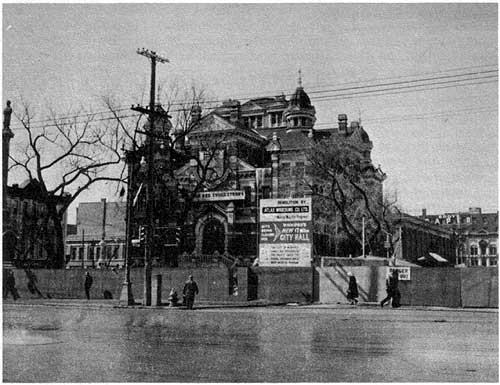

The idea of creating in Winnipeg a “grand” civic centre was not again put forward until the late 1950s and early 1960s when, as a result of another architectural competition, a vaguely “Classical” design was chosen for what became known as Winnipeg’s Civic Centre. [17] While the city gained a new city hall, the third in its history, it also lost its “grand old City Hall” when it was demolished in 1962. There were attempts to save the structure with groups in the city calling for its conversion to either a museum or a downtown library. [18] But those who argued for its destruction won the day and Winnipeg lost its most visible landmark. It also lost a firm link with the past.

Demolition of Winnipeg’s “grand old City Hall”, 1962

Source: Archives of Manitoba.

1. Historic Winnipeg Restoration Study (Winnipeg City of Winnipeg, 1974), p. 7.

2. Edith Paterson, Tales of Early Manitoba (Winnipeg: Winnipeg Free Press, 1970), pp. 78-79.

3. Alexander Begg and Walter R. Nursey, Ten Years in Winnipeg (Winnipeg: Times Printing and Publishing House, 1879), pp. 127-128.

4. Edith Paterson, Tales of Early Manitoba, p. 78.

5. Begg and Nursey, Ten Years in Winnipeg, p. 137.

6. For a map showing Brown’s Creek before it was filled in see Alan F. J. Artibise and Edward H. Dahl, Winnipeg in Maps / Winnipeg par les cartes, 1816-1972 (Ottawa: Public Archives of Canada, 1975), p. 16.

7. G. B. Brooks, Plain Facts About the New City Hall (Winnipeg: Walker and May, 1884), p. 3.

8. See, for example, Charles R. Tuttle, A History of the Corporation of Winnipeg, Giving An Account of the Present Civic Crisis ... (Winnipeg, 1883).

9. John W. Graham, Winnipeg Architecture, 1831-1960 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1960), p. 12. See also W. P. Thompson, Winnipeg Architecture: 100 Years (Winnipeg: Queenston House, 1975), p. 69.

10. Robert B. Hill, Manitoba: History of Its Early Settlement, Development and Resources (Toronto: William Briggs, 1890), pp. 527-528.

11. For a detailed account of Winnipeg’s development during this period see Alan F. J. Artibise, Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth, 1874-1914 (Montreal and London: McGill Queen’s University Press, 1975).

12. W. Van Nus, “The Fate of City Beautiful Thought in Canada, 1893-1930”, Canadian Historical Association, Historical Papers 1975, pp. 191-210.

13. Alan Gowans, Building Canada: An Architectural History of Canadian Life (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1966), p. 86.

14. Alan F. J. Artibise, “Winnipeg and the City Planning Movement, 1910-1915”, in D. J. Bercuson, ed., Western Perspectives I (Toronto: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974), pp. 10-20.

15. City Planning Commission Report, 1913.

16. Minutes of the City Council of the City of Winnipeg, 10 March 1913. See also “Competitive Design for the City Hall, Winnipeg, Man.”, Construction Magazine, 1913, pp. 147-160. For further information on the firm of Portnall and Clemesha see the Regina Morning Leader, 4 March 1913.

17. Thompson, Winnipeg Architecture, p. 66.

18. Winnipeg Free Press, 28 May 1949.

See also:

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Old City Hall Plaque (Princess Street, Winnipeg)

Page revised: 13 October 2012