by Frank Hall

Manitoba Pageant, Winter 1977, Volume 22, Number 2

|

Strong men and strong drink have played eccentric roles in the development of Manitoba. Since the earliest days of exploration, "Hooch" and Homo sapiens have been staggering down some weird and wonderful alleys in this province. They have done some outlandish things together, amusing, wicked, downright stupid things, and their brash departures from the path of conventional sobriety have led to some uproarious wingdings and bunghos - all, mind you, in the line of duty.

Hurumph!

So this is the story behind some of these "to-dos," the history behind history, as it were; the offbeat bits and pieces that seldom get into history books, that are nonetheless the essence of history itself.

Where to begin?

On December 8, 1866, Thomas Spence, loyalist, toper, and man of many parts, called a public meeting for 10:30 a.m. at the Court House, Upper Fort Garry, for the purpose of passing a resolution in favor of the establishment of a Crown Colony at Red River. However, Spence and four cronies, (his only supporters), it seems, knowing there would be strong opposition from American sympathizers in the settlement, met by design at 9:30 a.m. - one hour ahead of the appointed time for the public meeting.

They started the proceedings informally, strengthening their convictions by quaffing several snorts of Jamaica rum, and then passed a resolution and drafted a petition to Queen Victoria, "on behalf of certain worthy citizens," praying Her Majesty to hasten the establishment of a Crown Colony at Red River. Then, having thwarted the opposition, they closed their unorthodox assembly in high glee by lifting several toasts and raising three cheers to Her Majesty the Queen.

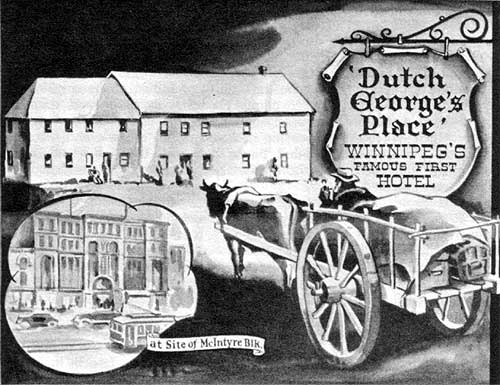

But just as their loyal huzzahs were fading away, the supporters of annexation to the United States appeared en masse on the Court House steps, prompt, ready, and well primed for the 10:30 meeting. They had come from a preliminary meeting of their own in "Dutch George" Emmerling's hotel, where the proprietor, a leading exponent of annexation, had strengthened his hold on their loyalty by dispensing liberal doses of his own "potent persuasive potion," known throughout the settlement as "Oh Be Joyful."

With spirits high on both sides, a heated argument developed, first outdoors, then indoors, where Emmerling's well coached advocates raised and carried a motion declaring the Crown Colony resolution to be null and void. Subsequent motions from one side of the house and the other were lost in noisy altercations; all rules of order went by the boards. "Then, after much ill-tempered shouting," as one observer put it, "the entire crowd sought a hasty and uproarious exit, some imagined with a view to continuing hostilities outside, where, to the contrary, a few sober souls hoped that the chill December blasts would quickly cool things off. The combatants continued on, however, to Mr. Emmerling's hotel, where an orgy was 'instituted' which ended about midnight in the demolition of his bar and the general destruction of his bottles and earthenware, not to speak of the irremediable damage to his fluids."

Thomas Spence, self styled "military officer, land surveyor, and practitioner of the legal profession," bounced back from this defeat with spirits undampened and, seeking greener pasture for the exercise of his political talents, went on to Portage la Prairie, then outside the Judicial District of Assiniboia), and there established the "Republican Monarchy of Caledonia," later to be known as the "Republican Monarchy of Manitobah."

Spence himself became President of the new political unit, whose boundaries included "thousands of square miles extending indefinitely into the parallels of latitude and longitude," the only defined limit being the western boundary of the District of Assiniboia.

One of Spence's first moves as President was to establish a system of taxation and tariffs on imports. After all, he couldn't run a government without money. Some people refused to pay either taxes or tariffs, but others paid up - and shut up. However, one of the noisy protesters, shoemaker Angus MacPherson, not only railed against the injustice of the levies but accused the government of using the income derived from taxes and tariffs to purchase liquid refreshments for the President and his Council instead of for the improvement of the colony. Then a great hassle developed.

MacPherson was warned to keep quiet or take the consequences, but he kept on repeating his accusations and urging the people to pay neither taxes nor tariffs until a strict accounting of government income and expenditure was made public by independent audit. The government was in no mood to take much of this, so they issued a warrant for his arrest on a charge of treason, and sent two constables to take him into custody. Somewhere along the way, however, "they fell on evil companions in the persons of several members of Spence's Council and at their bidding consumed large draughts of 'MacPherson's liquid evidence' against the government." Then, continuing on their way, they raised such a holler that MacPherson heard them while they were yet a long way off and made good his escape.

This ludicrous affair broke the back of Spence's "Republican Monarchy," and when the Duke of Buckingham wrote and warned: "that in your self-supporting Government in Manitoba you and your coadjutors are acting illegally ... and that by the course you are taking you are incurring grave responsibilities," the knock-out blow was struck. After this, on February 16, 1869, the Toronto Globe published the caustic obituary; "Since Spence has gone affairs are as usual and will, we trust, go on 'til the Colony of Manitobah becomes the County of Manitobah with a regular county organization under the new Dominion."

Some years before these alcoholic deviations ruffled the even tenor of life in Assiniboia, Old John Barleycorn went on a prolonged rampage at Fort Douglas, and Alexander Ross, the first historian of Red River, gives a striking account of his sojourn there.

"Governor Alexander McDonnell, who the people in derision nicknamed 'The Grasshopper Governor,' because he proved as great a destroyer within doors as the grasshoppers in the fields, prided himself in affecting the style of an Indian viceroy. The officials he kept about him resembled the court of an eastern nabob, with its warriors, serfs and varlets, and the names they bore were hardly less pompous; for here were secretaries, assistant-secretaries, accountants, orderlies, grooms, cooks and butlers.

This array of attendants about the little man was supposed to lend a sort of dignity to his position: but his court, like many another, where show and folly have usurped the place of wisdom and usefulness, was little more than one prolonged scene of debauchery. From the time the puncheons of rum reached the colony in the fall, till they were all drunk dry, nothing was to be seen or heard about Fort Douglas but balling, dancing, rioting, and drunkenness, in the barbarous spirit of those disorderly times.

The method of keeping the reckoning [of drinks consumed] on these occasions deserves to be noticed, were it only for its novelty. In place of the tedious process of [keeping account] by pen and paper and ink, the heel of a bottle was filled with wheat and set on a cask. This contrivance was, in technical phraseology, called the hour-glass, and for every flagon drawn off a grain of wheat was taken out of the hour-glass and put aside till the "house" [booze-up] was over; the grains were then counted and the amount of the expenditure ascertained. From time to time the great man at the head of the table would display his [false] moderation by calling out to his butler, 'Bob, how stands the hour glass?'

'High, your Honour! High!' was the general reply; as much as to say, 'they have drunk but little yet.'

Like the Chinese at Lamtschu or a party of Indian chiefs smoking the pipe of peace, the challenge to empty glasses went round and round so long as man could keep his seat; and often the revel ended in a general melee, which led to the suspension of half-a-dozen officials and the postponement of business, till another 'house' had made them all friends again. Unhappily, sober or drunk, the business they managed was as fraudulent as it was complicated."

The Hudson's Bay Company also had its troubles with Bacchus, as E. E. Rich points out. "As early as 1730, small beer was brewed at the posts from malt sent out: some ordinary beer was also sent out ready brewed, and a small quantity of strong beer for use on the voyage and for occasional issue at the posts. Beer caused no trouble; nor did the gifts of wine sent to allow the Chief to entertain at his table. But brandy had to be shipped in considerable quantities ... for the Indians would expect the gift of a dram, a pipe of tobacco and perhaps some prunes (of which they were most fond) at the start of trade, but such gifts made it difficult to require strict accounts for the quantity shipped and to stop pilfering.

The Indians would often take payment for their furs largely in brandy if it was available, and at trade-time the posts would require to maintain the strictest watchfulness to guard against attacks and fights. The temptation of the men of the posts to share in the drinking at trade-time was strong, and it met with constant warning and remonstrance.

Illicit shipments of brandy from England, sent to the men by their friends and relatives, were a separate and more important danger than access to trade-brandy. Here the Company should have been in a strong position since it controlled all shipping but, despite constant reiteration and a system of sealed consignments working in with rewards to informers, the brandy still found its way to the servants. Precautions to discipline the men and to restrict their access to brandy and to women were, however, at best palliatives. The real remedy ... lay in choosing such men as required no discipline."

Peter Fidler was such a man. He could handle his liquor in more ways than one, and one particular alcoholic experiment he made always comes to mind when one thinks about this outstanding fur trader, surveyor, book collector, and weatherman. He was in fact Manitoba's first weatherman, and he kept meticulous records of snow, rain, sleet, wind, fog, overcast, sun-shine, humidity and temperature - 180 years ago. He was a bit of a curiosity cat as well. Besides keeping temperature on Mr. Fahrenheit's thermometer, he wondered what would happen when he exposed different kinds of spirits to sub-zero temperature.

What happened? If you're looking for a heart warming belt on a cold evening, or if your radiator needs priming on a frigid morning, turn to Fidler's alcoholic freezing point gauge for proof of strength and purity - and be guided accordingly. Here it is.

York Factory:

December 31, 1794 - Holland Gin freezes at 17 below.

January 5, 1795 - English Brandy freezes solid at 25 below.

January I I , 1795 - Jamaica rum freezes at 31 below.

One other alcoholic deviation, the earliest in Manitoba known to the writer, and perhaps the choicest of all, is well worth the telling as a sort of final "one for the road."

In the autumn of 1619, the Danish navigator, Captain Jens Munk, made a landfall at Churchill River and drew his small ships, Lamprey and Unicorn, into a small inlet, known today as Sloop Cove. During the winter sixty-two of Munk's men died of scurvy and exposure, and at one point during that tragic season, Munk himself gave up hope of survival, so penned his farewell: "Herewith goodnight to the world and my soul into the Hand of God."

In the spring only Munk and two companions remained alive. They were weak and emaciated, but slowly regained their strength by nibbling on the green shoots that pressed through the lingering snow, obtaining there from the precious vitamin "c" which had been lacking in the scorbutic salted meat in the ships' stores.

Then one fine day when the sun was bright and strong, and when they themselves were in good health again, they went on board the Lamprey, set a bathtub on deck, filled it with gin, and bathed to their hearts' content in the stimulating suds.

What a sensation!

Skoal!

Page revised: 20 July 2009