Manitoba Pageant, Volume 18, Number 1, Autumn 1972

|

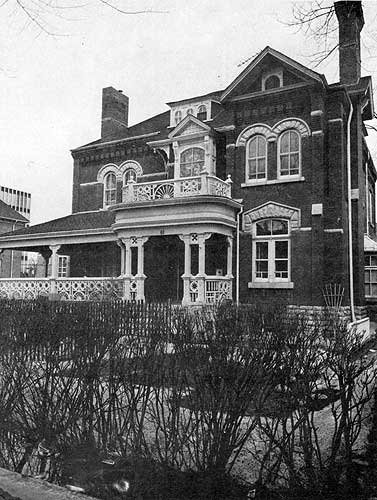

Macdonald House, known as Dalnavert in its heyday, was built for Sir Hugh John Macdonald in 1895. He and his family occupied it until his death in 1929. The stately home recently came into prominence through the news media when it was learned that it was to be torn down to make way for a high rise apartment block. The Manitoba Historical Society, under the then president, W. Steward Martin, Q.C., launched a drive to save the house. Through funds to be mainly raised by Television Bingo, the Society arranged to purchase the building with 150 feet of property at 61 Carlton Street in the fall of 1970.

Macdonald House (Dalnavert)

Source: Manitoba Historical Society

The objective was to restore the home to its 1895 condition, and operate it as a museum, both as an example of Victorian architecture, and the home of a very colourful citizen, a former Premier of our province, and a well-beloved magistrate.

Mr. John Chivers, Restoration Architect, with Mr. George Walker, Interior Designer, as assistant, were appointed for the work. No drawings showing the original layout of the building could be found. Since it had been converted into a rooming house after the death of Sir Hugh, major alterations had been made to the interior. In order to determine the location of rooms during Sir Hugh’s occupancy, extensive “stripping” was undertaken. This involved the removal of all floor coverings down to the original floor; removal of modern electric and plumbing installations; all recent wallboard and ceiling coverings, and non-original partitions. The front stairs, railing and newel posts were all in changed positions. These were carefully removed, and stored until the original location could be found.

During the life of the house, the position of the front stairway had been changed at least three times. When the Society took possession, the stairs led up from the main hall as one entered the front door; stripping proved that the stairs had at one time led up from the charming sunroom. This position was later corroborated by a lady who used to visit the house to take dictation from Sir Hugh, during the last two years of his life. However, there was an earlier position which was finally discovered after more stripping. Position of the servants’ stairway was also found during stripping of the kitchen. It had been removed, but has now been rebuilt in the correct location.

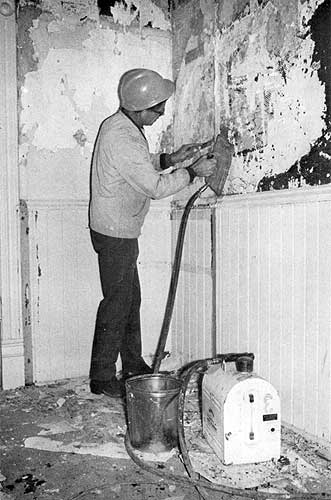

During the research and discovery process which began in 1971, Mr. Chivers and Mr. Walker took hundreds of photographs, and made detailed research drawings of each section being stripped. Most of the plaster walls and ceilings were in such poor condition they had to be removed, but before this took place, many layers of wallpaper were steamed off, down to the original paper. Samples of these have been photographed and an attempt will be made to match them.

Removal of many layers of wallpaper

Source: Manitoba Historical Society

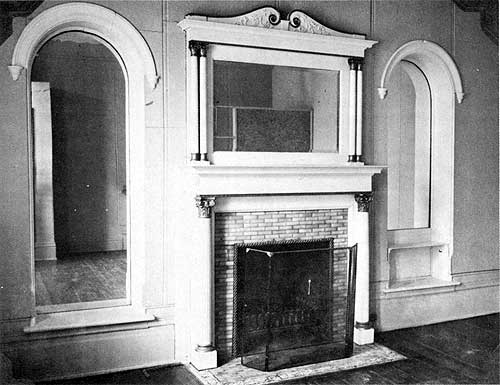

A fortunate find was made while stripping the living room. The fireplace is flanked by two mirrored alcoves. During the stripping process, these mirrors were removed for safety, and the original wallpaper, in practically mint condition, was found behind one of them.

Fireplace

Source: Manitoba Historical Society

Stripping was essential in order to determine the original layout of the building. While engaged in steaming off many layers of wallpaper in Sir Hugh’s study, marks appeared on the walls which indicated bookshelves had once been there. The section beside the fireplace was the first found, and thought to be a small amount of shelving for the number of books a magistrate would have owned. When the room was completely stripped, half of one wall and part of the next were found to have contained bookshelves. The original wallpaper in this room was a rich red, known as Turkey Red, much favoured in the Victorian age.

The kitchen presented a challenge to the restoration team. Layers of wallpaper were steamed off, and finally the original design was revealed. The complete stripping of the room yielded the locations of stove and sink, and a study of wear patterns on the floor showed where major traffic had been. This will help in positioning furnishings when restoration is complete. On the floor in front of the sink, two grooves worn by servants’ feet as they stood doing the dishes, were found. In the summer kitchen, which adjoins the main kitchen, interior boards on the outside walls were covered by newspapers and periodicals of the day, to keep cold winds out. The newspapers, dated to 1901, were found under the wall paper. On the floor are axe marks, made by servants as they split kindling for the auxiliary cookstove.

The beautiful oak ceiling, in the dining room, was covered by no less than fourteen coats of paint. While this was being stripped, a sag was noticed. Floor joists above had to be strengthened, allowing the sagging ceiling to be pulled up and strapped into position.

The basement area has been the scene of a tremendous amount of restoration work, since the entire structure had to be underpinned with concrete piles and new support posts, assuring a sound foundation for many years to come. At the same time, sewer lines were dug up, found to be corroded, and replaced. The basement plank flooring was in a rotted state, and was rebuilt. However, water marks from spillage of large quantities of water over the years, and four heavy support marks had given clues to where the laundry area was located. Plans are underway to reconstruct this area, using typical equipment of the period to furnish it.

A corner of the basement sheds light on an interesting facet of Sir Hugh’s beneficence. He was a very kind magistrate, and it is reputed that he often offered drifters a night’s lodging in his home before sending them on their way out of the city. Marks on the walls in an enclosed corner of the basement, such as those made by small beds, indicated this may possibly be the room reportedly used for this purpose. His charity in tendering lodging to unfortunate boys and young men was probably the forerunner of the Hostel which bears his name.

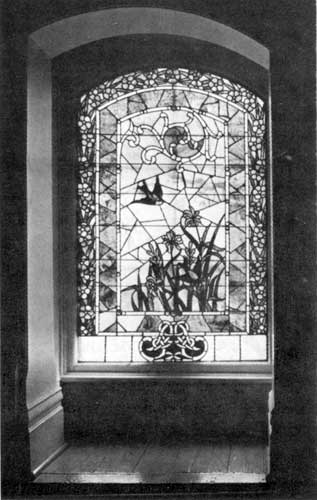

The bedrooms upstairs lead off a graceful hallway, with a balustraded arch spanning the ceiling at the centre. Towards the front of the house is an alcove with a beautiful stained glass window. This has been removed and stored for safety during the restoration process. The five bedrooms were all equipped with clothes closets, while Sir Hugh and Lady Macdonald’s bedroom and the daughter’s bedroom both have ornate fireplaces. An interesting note on the closets is that there are no rods for clothes hangers. A series of hooks were spaced about the perimeter of the closet, and garments were hung on these.

Stained glass window

Source: Manitoba Historical Society

In one of the closets the researchers discovered electric wiring of a very early vintage, leading to the original fuse box, with soft wiring for fuses known as “fuse wiring”. Wherever possible, switches, outlets, etc. will be retained, with new wiring to bring them up to modern building codes. While investigating electrical circuits, a speaking tube was discovered under layers of wallpaper. The tube ran from the private bathroom on the second floor to the kitchen. It was later replaced by an electrical callbox.

Adjoining Sir Hugh’s dressing room is the family bathroom, which will be graced by a bathtub (circa 1895) rescued from a priest’s residence during renovations. It was donated by a plumber interested in the restoration work. Messrs. Chivers and Walker recently were successful in obtaining enough salvaged tile to completely match portions of the existing tile in Lady Macdonald’s bathroom. A wash basin from a house of the correct vintage was donated by an interested citizen for the maid’s bathroom.

Simultaneously with other renovations the entire heating system was overhauled. The supply and return headers and all pipes in the basement area were flushed, cleaned and tested. These have been retained intact, and form part of the present heating system, which was converted to a new gas boiler. The original coal-fired hot water furnace has been disconnected, moved forward a few feet, to remain as an historical exhibit. However, many of the cast iron radiators, patented in 1887, had burst, due to not being used during the winter of 1970, when the contractor believed the house would be demolished. It was possible to obtain replacements from a salvage company, and other old houses being demolished. The pipe coil radiators had also burst, and matching castings had to be made for parts no longer available.

Another most important aspect of restoration is the exterior, which has been the scene of a lot of painstaking rebuilding. The wide verandah girdles the entire north and west sides of the house, and forms the graceful entry. Many of the joists and beams below the floor were deteriorated, so concrete piles and wood posts were installed, joists and beams renewed, and a new floor laid. Some railings and carvings had to be refashioned individually, using sound portions as models. This required many hours of precise work by cabinet makers and carpenters, in some places having to reconstruct very minute pieces. The original “gingerbread” on the verandah is reputed to have been imported from Virginia.

Extensive repairs to chimneys, cut stone and brickwork on the exterior have taxed the ingenuity of bricklayers, stonemasons and architect. The cut stone of the arches, sills, etc., was sandstone, an unusual choice, as most houses of comparable construction in the same area used Manitoba Limestone. The sandstone had begun to soften and fall off, and had to be replaced. Since Manitoba limestone would be historically correct, it was chosen for the replacement of some 200 pieces, cut to specifications.

Progress reports indicate the exterior work on Macdonald House will be completed this year. It included rebuilding the top sections of four chimneys, plus considerable brick repair to some walls. When deteriorated stonework was removed, it was discovered that brickwork had to be re-paired far beyond what had been expected. Because the attic is to be used as a museum, it was necessary to install insulation on the outside of the roof so rafters and roof boards would show inside. The weathered asphalt shingles have been replaced with cedar shingles in keeping with those first used.

Tenders for electrical work have been called. When that is completed, plaster on the walls and ceilings, and interior woodwork will be replaced. The tasks of painting and wallpapering will then be done with colours and papers matched as closely as possible to the originals.

A committee of the Junior League of Winnipeg has completed acquisition of equipment for the kitchen as one of its projects. The furnishing of the balance of the house is under the joint chairmanship of Miss Kathleen Richardson and Mrs. Kathleen Campbell. Developments of this important aspect of restoration will be reported in a later article.

So much variety has been revealed in ethnic building methods, that it has been decided to open the attic as a teaching museum, showing methods of construction, tools, fittings, etc. of the Victorian era. To this end, the walls and ceilings have been left unfinished to display methods of construction of the period. In their research of old premises to be demolished, the architect and interior designer acquired a collection of hinges, doorknobs, electrical fittings, keys, etc., to be grouped and displayed when the building museum is opened.

Hidden archway

Source: Manitoba Historical Society

The architect and the interior designer have been unstinting in their praise of the work of carpenters, bricklayers, stonemasons, painters, plumbers, and labourers, electricians and roofers who have responded with unparalleled devotion to the exciting challenge of restoring gracious Macdonald House. They are making it possible for people of present and future generations to step back into a part of the nineteenth century as it actually was. Within 3000 square feet of fascinating space Manitoba will have an historical attraction of international interest all citizens will be proud to possess and show.

The Manitoba Historical Society hopes to open Macdonald House in 1974, to coincide with the Centennial celebrations of the City of Winnipeg. When it is able to do this it will have been accomplished not by a handful of people, but by the active financial and moral support of Manitoba society as a whole.

The writer gratefully acknowledges the kind assistance of Mr. John Chivers, Restoration Architect, and Mr. George Walker, Interior Designer, and access provided to Macdonald House. Their progress report, well documented by pictures, was of inestimable value in the preparation of this article.

Page revised: 29 October 2022