by Michael Parke-Taylor

Toronto, Ontario

|

In the annals of Canadian art history, Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956) is revered as one of the foremost artists to have lived and worked in Western Canada. His paintings and drawings have come to epitomize urban views of Winnipeg as well as the appearance of the Manitoba landscape under intense prairie light. His significance was acknowledged by his peers in Eastern Canada when he was invited to join the famous Torontobased Group of Seven in 1932.

Although often characterized as a quiet introvert seeking solitude in nature in order to perfect his art, FitzGerald could be outgoing and even gregarious. He enjoyed the company of others and leapt at the opportunity to teach at the Winnipeg School of Art (hereafter WSA) in 1924. FitzGerald was also civic-minded and aware that the School of Art could play a role in the larger community. Along with School director C. Keith Gebhardt, FitzGerald taught and promoted the art of public mural decorations to his students in an effort to create a school of Western mural artists.[1] But another public activity in Winnipeg that occupied a considerable amount of FitzGerald’s time and effort—as well as that of many of his art world contemporaries—has thus far received little attention.[2]

FitzGerald’s Lady in Green, 1928, oil on canvas, 186 x 116 cm

Source: Musée d’art de Joliette, Gift of Jacqueline Brien, 1985.004

From the mid-to-late twenties, FitzGerald designed sets and costumes for the local little theatre company known as the Community Players of Winnipeg. Today there is little surviving visual evidence. Yet from 1925 to 1930, FitzGerald is known to have been designer for at least eight Community Players productions—and consulted on two others.[3] Using skills developed as a graphic designer and through his training in fine art, FitzGerald found that the theatre offered an outlet for his long-standing interest in literature and history.

The Community Players of Winnipeg was the brainchild of two lawyers, Harry A. V. Green and C.Alan Crowley, who founded the theatre group in 1921. Their mandate was in part to “provide facilities for the production of plays written by Canadian authors” and “to develop the arts and crafts ancillary to the drama, for example, the designing of scenery and costumes…”[4] Each year, the Community Players mounted four productions, an ambitious effort which lasted until 1937 when they closed under the name Winnipeg Little Theatre. During this period, the Community Players attracted the talent of major Winnipeg artists who were responsible for designing stage sets.[5]

The Community Players of Winnipeg production of Henry IV by Luigi Pirandello (17–20 October 1928) featured paintings by L. LeMoine FitzGerald. On the left of this cast photo is Donna Matilda Spina (Lady in Green, Musée d’art de Joliette) and on the right, Henry IV (location unknown).

Source: L. L. FitzGerald fonds, University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections, Winnipeg, PC 241, Box 2, fd. 3, 1-0348

The most likely catalyst for FitzGerald’s association with the amateur theatre in Winnipeg was Edith Sinclair (1883–1945).[6] Sinclair would produce or direct most of the plays with sets designed by FitzGerald starting with the February 1925 production of Aria da Capo written by Edna St. Vincent Millay. The only visual document of FitzGerald’s set for this play is a reproduction of a drawing that was published in the Community Players periodical The Bill along with set designs by artists Alex J. Musgrove and C. Keith Gebhardt for two other dramas.[7]

Edith Sinclair received her training in theatre at the School of Expression, Boston where she studied under theatrical luminaries including Burton James (1888–1951), Mordecai Gorelik (1899–1990) and Ellen Van Volkenburg (1882–1975).[8] In Winnipeg she fostered an interest in the Russian theatre which led to the formation and meeting of the Russian Rehearsal Club at the FitzGeralds’ residence in November 1926. According to a contemporary account, there was a presentation that evening on the amateur movement in theatre in Russia with special attention to directors Konstantin Stanislavski (1863–1938) and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko (1858–1943). It was also reported that the club watched a one-act “jest” by the Russian playwright Anton Chekov and that they were also studying his play The Cherry Orchard.[9]

That FitzGerald held an interest in Russian art, and likely by extension the Russian theatre, is evident from handwritten notes he prepared for a proposed lecture series at the WSA. In a manuscript dated 3 March 1927 titled Notes On Russian Art, FitzGerald copied at length a passage from Chapter five of Leo Tolstoy’s What is Art?: “Art is a human activity, consisting in this, that one man consciously, by means of certain external signs, hands on to others feelings he has lived through, and that other people are infected by these feelings and also experience them.”[10] Tolstoy’s definition of art could apply equally to the visual arts and the dramatic arts. While it is not clear to what extent FitzGerald was familiar with the look of the Russian theatre, it is worth quoting a review, which mentioned his set design for The Sea Woman’s Cloak (11–14 April 1928): “The stage settings by Lemoine [sic] Fitzgerald [sic] were suited to the eerie drama. The fullest use was made of the new stage medium of light to give expression to mood. The first scene on the rocky, cavernous seacoast was done in futuristic style after the fashion of the Moscow Art Theatre. Atmosphere rather than reality was the aim desired. It was secured through the use of color, light and forbidding shadow.”[11] For her part, Edith Sinclair’s fascination with the Russian theatre led her to take a course at the Chicago Art Theatre during the summer of 1928 with Ivan Lazareff (1877–1929) who was associated with the Moscow Art Theatre.[12] No doubt she would have shared this experience with FitzGerald and others upon her return to Winnipeg.

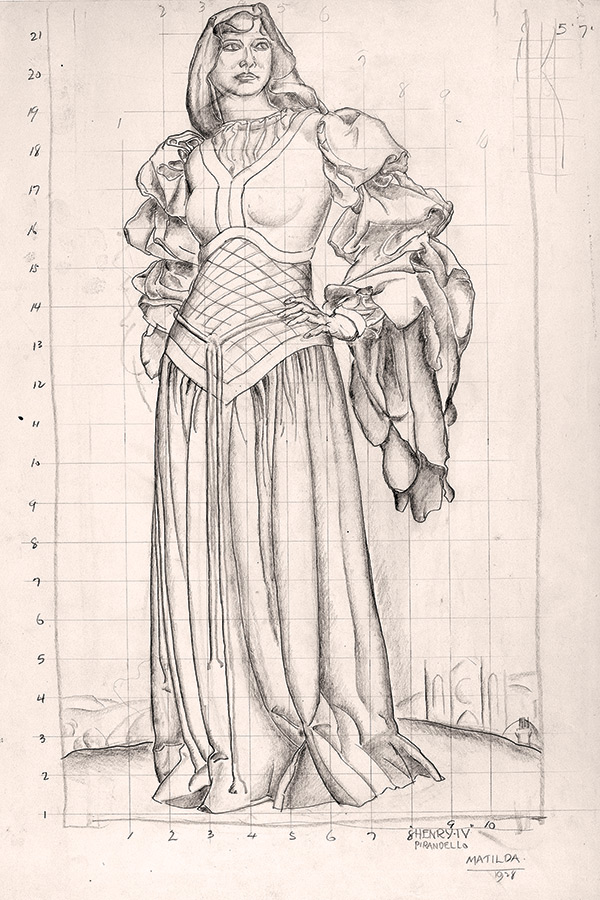

Left: FitzGerald’s Matilda (Matilda – Costume Study), 1928, graphite on paper, 61.2 x 46.1 cm.

Right: FitzGerald’s Dinolli (Dinolli – Costume Study), 1928, graphite on paper, 61.1 x 46.2 cm. At right is a small study for the head of Henry IV.Sources: Winnipeg Art Gallery, gift from Douglas M. Duncan Collection (G-70-85) and (G-70-86); photo by Serge Saurette

Another key friendship FitzGerald gained through a shared interest in theatre was with the writer, journalist and art critic Robert Ayre (1900–1980). Ayre’s first play Treasures from Heaven was performed by the Community Players, 19–20 February 1926. He was also involved with the Community Players as an actor as well as their publicist. Ayre is known to have commissioned WSA students Kevin Best, Robert Bruce and Irene Heywood to design covers for playbills between 1928 and 1932.[13] It was through the theatre and art circles that he came to know FitzGerald and became a great champion of his work. In the later forties, Ayre planned to write a monograph on the artist but the manuscript was never completed. Nonetheless, he did publish several articles on FitzGerald after the artist’s death in 1956.

The only artworks that have survived to document FitzGerald’s engagement with the theatre are three drawings and a painting related to a single production.[14] From 17–20 October 1928, the Community Players presented one of their most ambitious dramas, Henry IV, a play in three acts by the Italian writer Luigi Pirandello (1867–1936). The advance critical notices were enthusiastic and included notice of FitzGerald’s contribution: “L. Lemoine [sic] Fitzgerald [sic] of the Winnipeg School of Art, has worked out the stage design after a careful study of the period and an appreciation of the mood of this particular projection of it. The setting will be stately but simple—the gorgeousness of Henry’s eleventh century court will be revealed in the costumes. After the task of planning comes the labor of painting and hanging curtains—flats will not be used in “Henry IV”—dying, cutting and sewing costumes, making shoes, fashioning furniture.”[15] Another critic noted: “The set, designed by L. LeMoine Fitzgerald [sic] with the assistance of Miss Helen Gourlay, was a triumph in every way, quite the best that has been seen by this reviewer in Little Theatre performances or, in fact, any of the larger houses. The costumes were gorgeous and in excellent taste.”[16]

This page from a publication of The Community Players of Winnipeg reproduced stage sets by Alexander Musgrove, The Pine Tree (14–16 February 1924), L. LeMoine FitzGerald, Aria da Capo by Edna St. Vincent Millay (19–21 February 1925) and C. Keith Gebhardt, Ghosts by Henrik Ibsen (2–5 December 1925). FitzGerald’s design demonstrates his familiarity with the work of Russisan Art Deco designer Erté (1892–1990). FitzGerald owned the October 1926 number of Harper’s Bazaar which featured a work by Erté on its cover.

Source: The Bill, L. L. FitzGerald fonds, University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections, Box 1, fd. 15, 1-0705

A photograph shows the cast of Henry IV in their costumes and medieval setting designed by FitzGerald. Seated foreground right is Robert Ayre in his role as The Old Servant. Flanking the throne centre stage are two large framed pictures. Although these are barely visible, they may be identified as FitzGerald’s paintings of the characters Donna Matilda Spina (left) and Henry IV (right). The painting of Donna Matilda Spina (now titled Lady in Green in the collection of the Musée d’art de Joliette) was worked up from a preparatory drawing (inscribed ‘Matilda’ lower right) squared for transfer. This drawing would have been consulted by members of the Costume Committee responsible for making the outfit.[17] Likewise a squared-for transfer preparatory drawing was made as the study for the large pendant painting of Henry IV (location unknown). The figure in the drawing conforms in every detail to the pose and costume of the King in the painting—seen best in the background of a publicity still. Although FitzGerald marked the drawing ‘Dinolli’ suggesting it was for the costume of the character the Marquis Charles di Nolli, it is evident that the design was to serve for both di Nolli and Henry IV, whose disembodied, bearded and crowned head was sketched by FitzGerald at the right of the sheet.

Winston McQuillan as Henry IV and George Waight as Dr. Genoni in Henry IV. In the right background FitzGerald’s Henry IV, 1928, oil on canvas, 186 x 116 cm (location unknown).

Source: L. L. FitzGerald fonds, University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections, Winnipeg, PC 241, Box 2, fd. 3, 1-0336.

FitzGerald’s direct involvement with the Community Players waned after he assumed a heavier schedule upon his appointment as Director of the WSA in September 1929. Nonetheless, a love of theatre and a spirit of volunteerism seems to have run in the FitzGerald family. In 1932, FitzGerald’s 16-year old son Edward is listed as one of the electricians in the Community Players program for The Queen’s Husband by Robert Emmet Sherwood.[18] This experience and his father’s involvement with the theatre may have shaped his future. Edward FitzGerald would go on to a successful career in showbusiness working principally as a production designer (as well as an art director and set decorator) in the Mexican film industry from the 1940s to the early ‘60s.

Thanks to Nicole Fletcher, Brian Hubner, Donna Jones and Nathalie Galego for their assistance with this publication.

1. For more on public mural decoration and the WSA, see Marilyn Baker, The Winnipeg School of Art: The Early Years, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1984, p. 64. FitzGerald was responsible for a mural decoration representing the origins of jewelry design at Mitchell & Copp Ltd., 286 Portage Ave (reported Winnipeg Tribune, 9 February 1923) and a frieze featuring sixty figures at Baroni’s café and tea room, Portage Avenue and Donald Street (reported Winnipeg Tribune, 21 September 1923). Both decorations are no longer extant.

2. FitzGerald’s involvement with the theatre is referenced in Christine Lalonde, Beauty in a Common Thing: Drawings and Prints by L.L. FitzGerald, Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2004, p. 73, note 11.

3. Unless otherwise noted, the following is a chronological list of FitzGerald’s stage set designs for theatrical productions presented by the Community Players of Winnipeg:

Aria da Capo by Edna St. Vincent Millay (19–21 February 1925) produced by Edith Sinclair.

A Game At Mr. Wemys by Harry A. V. Green (19–21 March 1925) produced by W.K. Chandler.

The Man Who Married a Dumb Wife by Anatole France (22–24 October 1925) produced by Edith Sinclair.

The Dark Lady of the Sonnets by George Bernard Shaw ( 22–24 October 1925) produced by Helena MacVicar.

The Sea Woman’s Cloak by Amelie Rives (11–14 April 1928) produced by Edith Sinclair.

FitzGerald sets and costumes assisted by Helen Gourlay, Henry IV by Luigi Pirandello (17–20 October 1928) produced by Edith Sinclair.

FitzGerald (uncredited) assisted C. Keith Gebhardt, Ghosts by Henrik Ibsen (2–5 December 1925) produced by John Craig.

Chelkash by Maxim Gorky (26–27 March 1926) produced by Edith Sinclair.

FitzGerald consulting artist to John Russell for The Cradle Song by Martinez Sierra (30–31 January, 1–2 February 1929) produced by Edith Sinclair.

FitzGerald also designed sets for The Christmas Cycle of The Chester Mysteries (24 December 1930) produced by Edith Sinclair and presented at the Church of St. Michael and All Angels, Winnipeg and the following year at The Little Theatre of Winnipeg (22–23 December 1931) produced by Edith Sinclair.

4. Landon Young, “The Little Theatre of Winnipeg,” The Canadian Forum, VII, 84 (September 1927), 371. The development of the Little Theatre movement in Canada generated much commentary in artistic and literary circles during the twenties. The Canadian Forum issued a special Little Theatre number (IX, 98, November 1928) with a survey of the Canadian amateur stage in Canada including a report by Robert Ayre on the Community Players of Winnipeg.

5. The following, compiled by the author from programs and newspaper accounts, is a chronological (but not comprehensive) selection of productions by the Community Players of Winnipeg with sets designed by Winnipeg artists other than FitzGerald:

W. J. Phillips, The Pigeon by John Galsworthy (12–14 Dec. 1921).

W. J. Phillips, Squirrels by J. E. Hoare (16–18 February 1922).

W. J. Phillips, The Little Stone House by George Calderon (16–18 February 1922).

W. J. Phillips, Suppressed Desires by George Cran Cook and Susan Glaspell (16–18 February 1922).

W. J. Phillips, You Never Can Tell by George Bernard Shaw (18–20 May 1922).

W. J. Phillips, The Romancers by Edmond Rostand (7–9 December 1922).

W. J. Phillips, Wurzel-Flummery by A. A. Milne (7–9 December 1922).

W. J. Phillips, Master Pierre Patelin (1–3 February 1923).

W. J. Phillips, Dear Brutus by James M. Barrie (15–17 March 1923).

W. J. Phillips, Geminae by George Calderon (3–5 May 1923).

W. J. Phillips, The Death of Pierrot by Harry A. V. Green (3–5 May 1923).

W. J. Phillips, The Shadow of the Glen by J. M. Synge (3–5 May 1923).

Charles Comfort, Beyond the Horizon by Eugene O’Neill (1–3 November 1923).

W. J. Phillips, Prunella by Granville Barker and Lawrence Hausman (6–8 December 1923).

Alex J. Musgrove, The Pine Tree by Takeda Izumo (14–16 February 1924).

Alex J. Musgrove, Art and Opportunity by Harold Chapin (11–13 December 1924).

Charles Comfort, Interior by Maurice Maeterlinck (19–21 February 1925).

Charles Comfort, A Minuet by Louis Parker (19–21 March 1925).

C. Keith Gebhardt with some assistance from FitzGerald, Ghosts by Henrik Ibsen (2–5 December 1925).

W. J. Phillips, The Whiteheaded Boy by Lennox Robinson (27–30 January 1926).

H. V. Fanshaw, Conflict by Miles Mallenson (10–13 March 1926).

W. J. Phillips, Après la guerre by C. B. Pyper (12–13 November 1926).

Philip Surrey, Good Theatre by Christopher Morley (13–14 January 1927).

C. Keith Gebhardt, Liliom by Ferenc Molnár (9–12 February 1927).

Eric Bergman, No Smoking by Jacinto Benevento (25–26 February 1927).

C. Keith Gebhardt, The Man Who Died at Twelve O’clock by Paul Green (22–25 February 1927).

H. V. Fanshaw, The Lampshade by W. S. Milne (22–25 February 1927).

H. V. Fanshaw, The Jest of Hahalaba by Lord Dunsany (22–25 February 1927).

H. V. Fanshaw, To Have the Honour by A. A. Milne (30–31 March, 1–2 April 1927).

W. J. Phillips, The Land of Far Away by Harry Green (28–29 December 1928).

John Russell with FitzGerald as consulting artist, The Cradle Song by Martinez Sierra (30–31 January, 1–2 February 1929).

George Overton with Arthur Nelson and Don Phillip, The Devil’s Disciple by George Bernard Shaw (5–7 December 1929).

Fritz Brandner assisted by Caven Atkins and Joe Novak, Captain Brassbound’s Conversion by George Bernard Shaw (24–29 April 1931).

H. V. Fanshaw, The Farmer’s Wife by Eden Phillpotts (16–21 October 1931).

Alex J. Musgrove, Aren’t We All by Frederick Lonsdale (22–27 January 1932).

William Winter, The Mask and the Face by Luigi Chiarelli (2–3 February 1933).

6. Edith Sinclair was married to the art-collector Coll Claude Sinclair (1881–1975) who owned FitzGerald’s painting Poplar Woods (Poplar), 1929 (Winnipeg Art Gallery, G-75-76). He was the stage manager for his wife’s 1928 production of Henry IV featuring FitzGerald’s set and costume designs.

7. The Bill, April 1933, following p. 8 (unpaginated).

8. “Stage Does Not Imitate Life: Mrs. Sinclair, Director of Henry IV., Has Realistic Views on Drama,” Manitoba Free Press, 16 October 1928. The newspaper reporter identifies Ellen Van Volkenburg as Mrs. Maurice Browne (wife of the noted theatre producer).

9. R. H. A. [Robert Hugh Ayre], “Show Interest in Formation of Study Club,” 13 November 1926, [Manitoba] Free Press Evening Bulletin. A drypoint by FitzGerald of his wife titled Vally in The Cherry Orchard dates likely from this period. See Helen Coy, FitzGerald as Printmaker, A Catalogue Raisonne of the First Complete Exhibition of the Printed Works, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1982, no. 53.

10. L. LeMoine FitzGerald quote from Leo Tolstoy What is Art?—Notes on Russian Art, Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald fonds, University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections, Winnipeg 11-0184.

11. R. H. “Little Theatre Players Score in Irish Drama—Exceptionally Fine Performance Given in ‘The Sea Woman’s Cloak’,” Winnipeg Tribune, 13 April 1928. No photographic documentation exists of FitzGerald’s set design.

12. “Producer Gives Play Much Study—Edith Sinclair Brings Wide Experience to Little Theatre for Opening Show,” Manitoba Free Press, 6 October 1928.

13. Baker, Winnipeg School of Art, p. 66. See also “Art,” Manitoba Free Press, 20 October 1928. For a report by Ayre on amateur theatre in Winnipeg in the issue of The Canadian Forum dedicated to Canadian Little Theatres, see Robert Ayre, “The Community Players of Winnipeg,” The Canadian Forum IX, 98 (November 1928), 55–56.

14. Apart from a photo of the set from Aria da Capo (see page 48, centre), the only stills published of plays for which FitzGerald acted as designer are in the Journal of Expression [Little Theatre Number] 3, no. 4 (December 1929), following p. 208 (unpaginated) The Man Who Married a Dumb Wife and following p. 221 (unpaginated) The Cradle Song and The Mock Emperor [Henry IV].

15. “Mediaeval Court Revived in Play—‘Building’ Little Theatre Production Is Work for Many Busy and Earnest Hands,” October 1928. Unidentified press clipping, Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald fonds, University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections, Winnipeg. See http://hdl.handle.net/10719/10482

16. “Fantastic Play by Pirandello—Winnipeg, Through Community Players, Gets Its First Taste of Italian Dramatist,” Manitoba Free Press, 18 October 1928.

17. Another preliminary drawing of the character Matilda is in the Collection of the School of Art, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg (12-0512.). Florence Brigden, wife of FitzGerald’s close friend Arnold O. Brigden, who managed the printing firm Brigdens Limited, and Thelma Ayre, wife of Robert Ayre, both served on the Costume Committee for Henry IV.

18. The Bill 5, no. 1 (October 1932), Winnipeg Little Theatre. As a youngster, Edward (b 1916) was encouraged by his parents to make marionette puppets and collaborate in puppet shows with his mother.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 1 May 2021