by Thomas Shay

Welton, East Yorkshire, England

|

The Europeans who settled North America lived in an age of wood. They used wood to heat and cook, to build houses, barns, and stores, to fence fields, to make carts, boats, yokes for oxen, ploughs, hay rakes, and other farming tools as well as for furniture, buckets, tubs, brooms, toys, and a host of other household items. Wood was also widely used and a crucial commodity on the southern Manitoba prairies.

The Europeans who settled North America lived in an age of wood. They used wood to heat and cook, to build houses, barns, and stores, to fence fields, to make carts, boats, yokes for oxen, ploughs, hay rakes, and other farming tools as well as for furniture, buckets, tubs, brooms, toys, and a host of other household items. Wood was also widely used and a crucial commodity on the southern Manitoba prairies.

The settlement that Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, founded at Red River in the heart of the Hudson’s Bay Company trading empire was well situated between sprawling grasslands to its west that supplied traders with bison meat and hides and fur-rich forests, lakes, and streams to its north and east. [1] However, timber was in short supply. Wood was scarce as early as the 1820s and by 1858 great swaths of riverbank had been cleared of trees. The demand from the growing population soon outstripped the local supply and people relied more and more on imported wood. How the settlers, commercial enterprises, and the government handled this supply and demand situation makes for a fascinating economic and social history.

This article looks at the wood economy of the Red River Settlement from its beginnings in 1812 until the introduction of railway links between the United States and eastern Canada in the early 1880s. I describe local forest resources, wood uses, and how those uses affected society and the environment by drawing upon early accounts from individuals, in government records, as depicted in historical photographs and paintings, recorded in land and forest surveys, and through analysis of wood and charcoal fragments retrieved from archaeological sites. I also discuss how newcomers managed the scarce resources of the eastern prairies. I conclude that they failed to manage their forest resources wisely. Although the government eventually imposed some regulations on timber cutting in an effort to conserve the natural resources of the area, settlers adapted to the situation not by managing what they had, but by becoming dependent on wood brought in from afar.

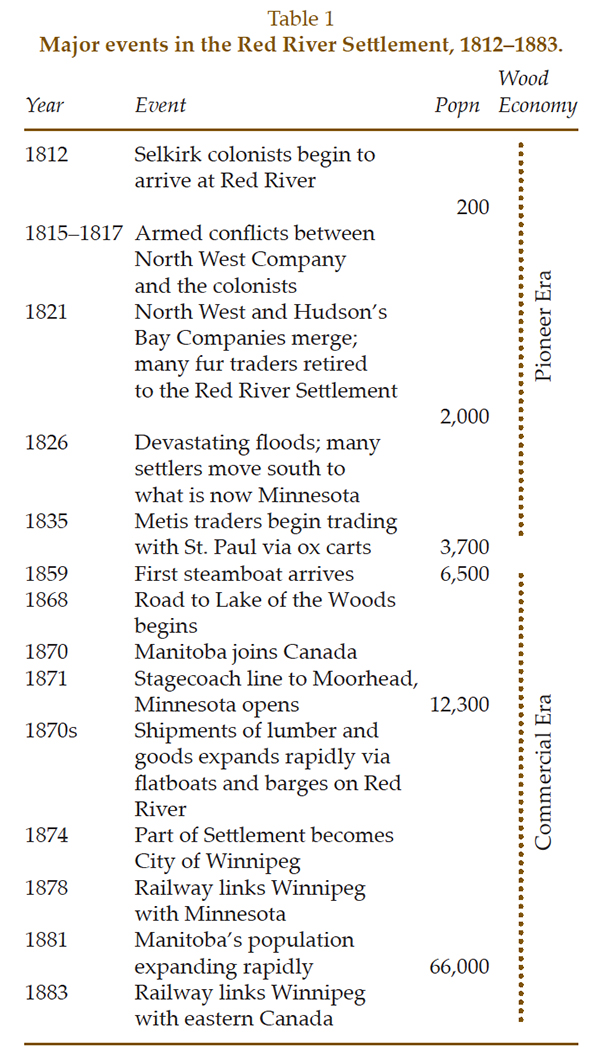

The Earl of Selkirk recruited the original colonists from the highlands and elsewhere in Scotland, plus some from Ireland. Upon arrival, they were allocated farm lots along the Red River north of the confluence of the Assiniboine and Red, popularly known as “The Forks.” [2] The settlement’s population grew rapidly from a mere two hundred in 1814 to two thousand by 1825, due in large part to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s merger with its fur-trade rival, the Northwest Company, in 1821. [3] By this time, settlers included Scots, Irish, English, Swiss and even De Meurons mercenaries from Germany. More than half the population consisted of Cree and Ojibwa people, French voyageurs, and the Métis—a people of mixed European and Aboriginal parentage. [4]

The Red River Settlement was in transition between the Pioneer and Commercial Eras when photographer Humphrey Lloyd Hime

visited in the fall of 1858 as a member of the Hind Exedition from Canada. Wood was the dominant material used for construction of

buildings, as seen in this view of Andrew McDermot’s store near Upper Fort Garry.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Hime HL 14, N12551

After devastating floods in 1826, some colonists moved south while those who remained began to rebuild all that had been lost. Less than a decade later, the Hudson’s Bay Company regained economic and political control of the region when they bought out Lord Selkirk. [5]

Beginning in 1839, groups of Métis traders travelled 800 km (500 miles) by ox cart to St. Paul, Minnesota to exchange furs and buffalo hides for household goods. By 1858, six hundred carts carrying hundreds of tons of cargo were plying the route. [6] Steamboats began arriving in 1859 and soon free traders built a few stores, hotels, and saloons near The Forks, creating the nucleus of what would become Winnipeg. [7]

Over seventy years, the wood economy of Red River Settlement shifted dramatically from a “Pioneer Era” (1812–circa 1860s), when families cut most of their own wood for fuel and building, to a “Commercial Era” (1860s–1880s) that saw the expansion of lumber imports, the rise of lumber companies, and the control by the Canadian federal government of timber harvesting.

From the start, the Settlement lacked adequate wood supplies. Most (80 percent) of the land within 30 km (18 miles) of the centre of the Settlement was either prairie or marsh. [8] Forests were confined to the borders of rivers and scattered groves (see a map on the following page). [9] Governor Miles MacDonell wrote:

“The Country on West side the river ... is all a plain with a belt of wood on the river edge of irregular depth. ...in many places the plain reaches to the river bank. And the East side ... is well wooded. The wood consists of Oak, Elm, poplar, Liard or cottonwood, ash, Maple, &c., there is no pine or cedar. Rivers falling into the Red River are generally wooded on both sides. It would be proper to make reservations of wood on [the] East side [of the] R. R. in the proportion of about 100 acres for every five settlers ...” [10]

Early maps and descriptions confirm these impressions. Aaron Arrowsmith’s 1816 map shows a strip of forest on the east side of the Red River, but only prairie on the west. He describes the area south of The Forks as “Woods interspersed with small prairies extending for several miles” and the area beyond the forest belt on the east of the Red River as “Plains interspersed with tufts of wood.” [11]

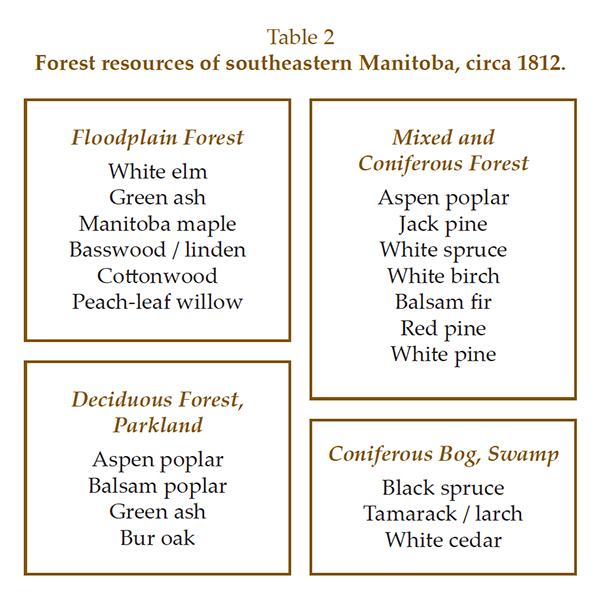

Based on recent forest surveys, the species that bordered the Red and other prairie rivers included white or American elm (Ulmus americana), green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), Manitoba maple (Acer negundo), peachleaf willow (Salix amygdaloides), eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides), and, in favourable locations, basswood (also known as linden or whitewood, Tilia americana). [12] Stands of bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) grew on higher ground while islands of trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) and balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera) dotted the open prairie (see Table 2). River valleys and prairie groves contained limited building timber, so much had to be acquired from distant forests.

Based on recent forest surveys, the species that bordered the Red and other prairie rivers included white or American elm (Ulmus americana), green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), Manitoba maple (Acer negundo), peachleaf willow (Salix amygdaloides), eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides), and, in favourable locations, basswood (also known as linden or whitewood, Tilia americana). [12] Stands of bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) grew on higher ground while islands of trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) and balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera) dotted the open prairie (see Table 2). River valleys and prairie groves contained limited building timber, so much had to be acquired from distant forests.

To the east of Red River lay huge tracts of forests covering more than 16,000 square kilometres (6,000 square miles). [13] In the early days of the Settlement, lowland peat bogs probably covered two-thirds of this land, supporting black spruce (Picea mariana), tamarack/larch (Larix laricina), and eastern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis). Expanses of jack pine (Pinus banksiana) and, in places, red pine (Pinus resinosa) could be found on dry sandy ridges and uplands. Scattered groves of eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) grew on slightly moister sites. [14]

Jack pine also grew on soils with intermediate moisture where it was joined by white spruce (Picea glauca), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), and white birch (Betula papyrifera). Aspen was common throughout, on dry to wet soils, either in pure stands or mixed with the other species. Groves of deciduous trees bordered major streams.

Before commercial logging, these forests contained enough standing timber to build thousands of houses. [15] Once cut, it took replacement trees decades to mature due to the short growing season and low soil fertility in the area. [16] Throughout the Settlement’s history, people obtained their firewood and construction timber in one of three ways:

1. Households harvested their own wood, sometimes with neighbours or hired workers. John McDougall, who lived in the Settlement from 1842 to 1862, tells of a cooperative “bee” that rafted logs to a building site where a church was being enlarged. [17] A crew then sawed the timber and left it to season until autumn when the Hudson’s Bay Company carpenter completed the building.

2. They bartered or purchased from a woodcutter. In 1816, the governor of the Settlement bought one hundred pieces of squared timber from a local “Freeman” for Fort Douglas. [18] Samuel Taylor’s diary records that in February 1864, a load of hay was exchanged for poplar building logs. [19] Rev. George Young purchased firewood in 1868: “The fuel brought by the natives to our Winnipeg market was generally of the poplar-pole sort ...” [20]

3. They purchased from a commercial outlet. John Inkster’s store supplied hundreds of planks to the Hudson’s Bay Company as early as 1850. [21] Merchants advertised lumber and firewood for sale in The Nor’Wester newspaper’s first issue on 28 December 1859.

When the population was thinly scattered along the Red and Assiniboine rivers, most households relied on the first two methods for obtaining wood. [22] They gathered much of their own firewood locally, but many brought building logs from a distance. [23] Axe men usually felled trees during the winter and hauled them to a riverbank to await the spring runoff when the logs could be rafted downstream. As the limited local building timber dwindled, people cut upstream along the Red and Assiniboine, the Red’s eastern tributaries such as the Seine, Rat, and Roseau, and from wooded ridges east of the Red River (see Figure 1). [24] By the late 1840s, they had to cut wood as far away as the upper Roseau and Red Lake rivers in northwestern Minnesota. [25]

Figure 1. Vegetation map of southeastern Manitoba at the time of the Red River Settlement, based on early land surveys.

Source: Adapted from T. R. Weir, Economic Atlas of Manitoba, page 21

Travelling for wood was time-consuming. The Rev. R. G. MacBeth recalled: “... in certain seasons of the year the settlers were away from home ... during the whole week.” [26] Samuel Taylor wrote that oxen often hauled large loads of firewood from as far away as Lake Winnipeg. He noted in his diary, “prepared a meal for a day’s excursion to obtain building wood 48–64 km [30–40 miles] away.” [27] Diarist Peter Garrioch often mentioned expeditions to collect wood to build a house from locations east of the Red River. [28] In entries from 1845 to 1847, he describes trips to the “Pines” (probably near Birds Hill), the “Far Pines,” “Cedars,” and “Anderson’s Pines.” In all, Garrioch’s crew hauled 222 beams of wood, including cedar and tamarack. They also hauled six loads of cedar shakes and two loads of cedar wood for framing.

Many men were employed in the cutting of timber, sometimes at the expense of other occupations. Aboriginal and Métis men cut and rafted firewood, building timber, and fencing. [29] Métis loggers cut tamarack from swamps near the Rat River to make wooden boardwalks for Winnipeg. [30] Meanwhile, a Hudson’s Bay Company trader complained that many of his fur trappers had left to work in the logging camps. [31]

Downed trees were trimmed and floated as near to a building site as possible before the planks were sawed. Carpenters erected scaffolds to hold the logs for cutting or used “pit” saws. [32] To build a pit saw, a rectangular pit about 2 m (6 ft.) deep was dug. Each log was debarked with adzes and the intended cuts were marked with chalk or charcoal, then the log was laid over the pit. One sawyer climbed into the pit while another stood above, each holding one end of a 2.4 m (8 ft.) saw. [33] Being a top sawyer was not easy, but the bottom sawyer’s job was “laborious ... in the extreme; sawdust poured down on his sweating face and bare arms, and down his back ...” [34] Thankfully, sawmills replaced pit saws during the early 1870s. [35]

Building was, of course, a major activity from the Settlement’s early days. In the first year, a 15 x 7.5 m (50 x 25 ft.) house and another measuring 4.5 x 6.6 m (15 x 22 ft.) were constructed. Crews also began work on Fort Douglas, named in honour of Lord Selkirk’s family, using logs and timbers rafted downriver from the company’s post at Pembina. [36] By 1822, the 32 x 40 m (132 x 105 ft.) stockade featured a large hexagonal blockhouse, one large house, six smaller houses, a carpenter shop, an icehouse, a mill, a stable, a potato house, and a forge. Outside the fort, were 126 houses for a population of 1,200. [37] That same year, the Hudson’s Bay Company built Fort Garry, named after the Company’s deputy governor, at The Forks. The original Fort Garry was destroyed by flood in 1826, but was rebuilt on higher ground in 1835 as part of a more elaborate establishment.

Most builders used a technique known as “Hudson’s Bay Style,” “Red River Frame,” or “posts-on-a-sill.” Scandinaviansdeveloped it and settlers of New France (Quebec) brought it to North America. From there, French fur traders took it west where the Hudson’s Bay Company and Red River settlers adopted it for homes, churches, stores, schools, and outbuildings. Red River Frame remained popular until the 1870s. [38]

To build a house, first a foundation of fieldstones was put in place. A frame of squared oak timbers was laid on this. Next, vertical posts were erected at each corner and along each wall, mortised into the foundation timbers. Grooves were cut in each post, then lengths of timber were slid into the grooves, creating walls. Doors and windows were set between two minor uprights. The technique needed time and skill, but the result was remarkably strong. [39]

About a third of all wood used in the Settlement went for building. The 1856 census lists 6,523 people and includes mention of 922 houses, 1,232 stables, 399 barns, 17 schools, 56 shops, 16 windmills, nine churches, nine watermills, and one gaol. [40] Each modest-sized house needed five to six thousand board feet of lumber including one thousand board feet in shingles. [41] For roofing, people favoured straw thatch as it was “light, watertight and durable.” [42] Few could afford cedar shingles, and those of oak warped in the summer heat.

Most homes were modest. The 1856 census lists 597 houses valued at between £12 and £25, but 25 houses were valued at £300. [43] Many of the £300 houses were large, Georgian-style buildings constructed of stone or wood, with one- or two-storeys, pitched roofs, rectangular windows, and ornamented front doors. [44] The rectory at St. Andrew’s, built between 1844 and 1849, is an excellent example. The 16 m-wide (54 ft.) building has a symmetrical facade with two windows oneach side of the central door and five windows in the second storey. Archdeacon Reverend Cochrane oversaw the building of the rectory and described craftsmen’s contributions in his diary for 29 December 1844:

“Stones, lime, shingles, boards, timber, and labour were cheerfully contributed. The shingle makers proposed to give 10,000 each; the lime burners 400 bushels each; the masons proposed to dress the stones for one corner and lay them gratis. Boards and timber were promised in the same liberal manner....” [45]

Builders used a half-dozen kinds of wood. Those listed in the Hudson’s Bay Company inventories and purchase orders for the 1840s were, in order of abundance, oak, pine (I presume a generic term covering both spruce and pine), poplar, cedar, elm, and larch. [46] Carpenters used oak for framing, pine (or spruce) for floors, and whitewood (basswood) for furniture. Less-regarded poplar was peeled to make fence poles and house partition walls. [47]

Local carpenters built tables, chairs, and chests from oak or whitewood. Some wealthy families imported their home’s wood detailing and furniture from England or the United States with Red River carts bringing oak and walnut woodwork, sashes, doors, and walnut furniture from St. Paul in 1862. [48]

Oak and spruce were the most popular building woods identified at 19th-century archaeological sites and historic houses from within the Red River Settlement. Sampling consisted of two fur-trade sites, three Métis farmsteads, and three standing houses totalling eight locations. Oak wood was found at five of the eight locations, spruce at four (see Table 3). [49] Most of the remains uncovered at Fort Gibraltar were of local tree species, but at Upper Fort Garry only a third were local. [50] The other two-thirds were conifers: spruce, jack pine, white and red pine, larch, cedar, and fir, all probably brought from eastern Manitoba. We also found a few shavings of black cherry (Prunus serotina) that must have been imported as the nearest trees are 500 km (300 miles) away in southeastern Minnesota. [51] With its golden sheen and smooth grain, cabinetmakers ranked it second only to black walnut. [52]

Table 3: Wood and charcoal remains from 19th-century archaeological sites and houses in the Red River Settlement.

Daily life required a variety of utilitarian wooden tools and containersincluding the ubiquitous “pans,” circular oak tubs with straight sides and holes for handles, used for making butter, cheese, soap, and candles. [53] As early as 1818, coopers were fashioning such pans as well as oaken barrels and buckets. [54]

Boats, birch bark canoes, and ox carts were built to carry people and goods, while ploughs, harrows, threshing and carding mills, reaping and winnowing machines were among locally made farming implements. Public works involved building wooden bridges and stabilizing muddy roads with wood bundles. In 1855, workers built seventeen bridges, one 38 m (125 ft.) long and 6 m (19 ft.) wide; in 1858, they covered 2,987 m (3,268 yards) of “gumbo” road with faggots. [55]

Alexander Ross wrote in 1858, “Ere long, brick must necessarily be adopted as a substitute for wood.” [56] However, builders did not use them until the 1870s.

The quantity of wood used for all types of building was significant, but most wood was burned just to stay warm during the long, cold winters. Robert Coutts writes:

“When the temperature reached minus twenty or thirty Celsius, as it often did in the depths of winter, the stoves and fireplaces were kept constantly burning. Gathering wood for fuel was an essential part of life in the Parish. Each fall, residents had to travel some distance to the various wooding sites on Lake Winnipeg or east of the Red River, where two or three days were needed to chop and stack the wood for transport back to the settlement. The firewood was hauled home on oxen-pulled sleds or on Red River carts. A large quantity of wood was needed to heat the average home through the winter months, and settlers were often forced to return to ‘the pines’ one or more times to replenish their depleted supplies.” [57]

I estimate that each household burned twenty to thirty cords of wood per year just for heating and cooking. [58] A cord represents a stack 1.2 m (4 ft.) high by 2.4 m (8 ft.) long and 1.2 m (4 ft.) wide, equal to two hundred 8-10 cm (3-4 in) saplings or two trees, 45-50 cm (18-20 in) in diameter. [59]

Firewood became increasingly scarce as the settlement grew. As Hudson’s Bay Company Governor Sir George Simpson testified before a House of Commons Committee in 1857, “The question of a supply of timber for building purposes is not so important as the requirements of the same material for fuel...” [60] One settler of that time, Robert Ballantyne, wrote, “Ere long, the inhabitants will have to raft their firewood down the river from a considerable distance.” [61] Firewood was at times so scarce that people were forced to burn some of their prized possessions. Historian Diane Payment describes the disastrous winter of 1858-1859: “As hunters had been out of firewood, they burnt upwards of 50 of their carts.” [62]

Written records show that stoves and fireplaces at Fort Garry burned oak, poplar, and less frequently, pine (probably spruce). Although more expensive, oak may have been preferred due to its high heat yield. [63] Oak’s higher cost is reflected in the proportions of charcoal found at three archaeological sites: oak made up forty-two percent of the charcoal from Upper Fort Garry, but comprised only seven to eight percent from two Métis farmsteads (see Table 3). [64]

To save energy and exclude drafts, people chinked their houses with mud and straw, sometimes adding buffalo hair to the mix. A few covered their outer walls with stucco or clapboard. Windows and doors were kept small to conserve heat. [65] Early on, fireplaces of stone or baked clay were common, although more efficient cast-iron stoves gained in popularity after 1820. [66] To further encourage stove use, the Council of Assiniboia scrapped the import duty on them in 1847. [67] However, most families still baked in outdoor ovens built of a frame of green willow branches plastered with clay. [68] Besides domestic heating and cooking, people heated water for bathing, washing dishes and clothes, for making starch, for dyeing cloth, and for making salt. [69] They also burned wood to brew beer and distill spirits. [70]

The small windows that made homes easier to heat also resulted in rooms that felt gloomy and dark, so builders took to plastering and whitewashing the inside walls. Limestone chunks (calcium carbonate, CaCO3) were collected from outcrops along the Red River, broken into small pieces and piled into a stone kiln fired with wood or charcoal. Several days of burning converted the limestone into calcium oxide (CaO), or quicklime. Builders mixed the quicklime with water and clay or sand to make plaster that they applied to interior walls and chimneys. As it hardened, the quicklime combined with carbon dioxide in the air to become calcium carbonate again. For paint, they used a thinner mixture. [71] Though it lightened interiors, creating enough quicklime to plaster a typical house burned the wood from 0.2 ha (0.5 ac.) of forest. [72]

People also burned wood to make charcoal. Charcoal delivered the same amount of heat, weighed less, and burned hotter and cleaner than wood. Producing it was a time-honoured endeavour throughout Europe and colonial North America, requiring great skill. [73] A team of charcoal burners would set up in a forest clearing, preferably near stands of oak and ash. They cut wood into 1.2 m (4 ft.) lengths and split it lengthwise into pieces several cm (inches) thick that they piled into a large mound around a hollow centre that served as a chimney. To ensure controlled burning, the crew covered the mound with soil before inserting a charge of burning charcoal. They monitored the burning for several days, lest the fire go out or, alternatively, burn all the wood to ash. When cooled, the crew had the grimy job of packing the charcoal into sacks. A cord of wood yielded 35 to 45 bushels of charcoal. [74] In the early days, blacksmiths and farriers used large quantities of charcoal in their forges, perhaps up to a couple of hundred bushels annually. [75] Excavations at the blacksmith shop at Lower Fort Garry recovered poplar charcoal remains. [76]

Wind and waterpower had been widely used for grinding grain and sawing wood, but the advent of the steam engine in the 1860s increased the use of wood fuels. Even small engines burned a cord or more of wood a day. [77]

The arrival of steamboats in 1859, the building of a road from Lake of the Woods in 1868, the opening of a stagecoach line in 1871, and the coming of railways in the late 1870s all expanded trade and immigration. The vessel Anson Northup was the first steamboat to dock at The Forks, arriving on May 23, 1859 with a shriek of its whistle as jubilant crowds celebrated its four-day 400-km (250-mile) journey down the Red River from near Fargo, North Dakota. [78] In a fever of competition, transport companies launched a dozen or more steamboats during the next two decades and, by 1882, more than twenty boats plied western rivers. [79] Steamboats became larger, ranging up to 218 tons, able to haul ever-greater cargoes. Some clever soul soon reasoned that a steamboat could move even more tonnage by towing barges. On one trip, the 36-ton Pluck towed three barges laden with freight, including a good deal of lumber. [80] Though they carried tons of wood for commercial sale, large steamers also burned massive quantities as fuel. The Anson Northup is said to have used nearly a cord of wood an hour and had to stop frequently to cut wood along the shore. [81]

Large, flat-bottomed boats that were poled rather than towed also joined the shipping frenzy. A thriving flatboat-building industry emerged along the Red River in North Dakota beginning in the 1860s. Each flatboat of Whitford & Harris, a prominent firm engaged in the trade, carried ten to twenty tons; a decade later, such boats carried up to thirty tons. Shippers used barges and flatboats to transport seed grain, flour, machinery, farm implements, and lumber destined for prairie farms and settlements, including tens of millions of board feet of lumber to Red River over the next several decades. [82]

Wood was an essential resource for the steamboats that plied Manitoba waters from the 1850s to the early 20th century. In this view by

Winnipeg photographer Israel Bennetto taken around 1883, the Marquette is standing at anchor, loaded with firewood to fuel its boilers.

Built in 1881 for Peter MacArthur’s Northwest Navigation Company, the Marquette saw service on the Red and Assiniboine rivers.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Transportation - Boat - Marquette 1, N13054

Less than two decades after the first steamboat arrived, the first train left Winnipeg for St. Paul, Minnesota on 9 December 1878. [83] Crews completed the Canadian Pacific’s main line from Fort William, Ontario to Winnipeg five years later. [84] Railways hauled lumber but building them also used much wood. Construction of that line required cutting of vast quantities of timber from the Whitemouth River area for ties, locomotive fuel, and more. [85] Each mile of track needed three thousand “sleepers” or cross ties, 2.4 m (8 ft.) long, 15 cm (6 inches) thick, and 15 cm (6 inches) wide, or 34 board feet. Spaced every 0.5 m (21 inches), this added up to an astonishing 102,000 board feet per mile. [86]

Timber cutting moved even farther afield as thousands of immigrants poured into Manitoba by boat, cart, stagecoach and, now, rail. [87] Crosscut saws could be heard along the Winnipeg, Whitemouth, and other rivers and around Lake Winnipeg and Lake of the Woods as well as in northwestern Minnesota. In the early 1870s, only a handful of companies were operating, but soon lumber milling became Winnipeg’s chief industry. The earliest sawmills were erected on the banks of the Red River while later mills were located closer to logging operations. [88] More than twenty mills were operating by 1880, but lumber imports from the United States continued. [89]

Between 1859 and 1870, the year Manitoba joined Canada, the Settlement doubled in size to over twelve thousand people. [90] Winnipeg, which had been a small part of the Red River Settlement, grew into a leading urban centre and the provincial capital, touted as the “Gateway to the West” as towns and villages sprang up across the new province. [91] By 1870, Winnipeg boasted about thirty buildings including eight stores, two saloons, two hotels, a mill, and a church. [92] Within a few years:

“... [Winnipeg had] flour and saw mills, sash and door factories, a brewery and a distillery, dealers in furs and hides; grocery, dry goods, furniture, hardware, drug, book stores and butcher shops; tobacconists and wine merchants, tailors and outfitters; fuel dealers; lumber yards, builders and contractors; agricultural implement and seed dealers, blacksmiths, harness shops and livery stables, hotels, banks, land offices and real estate dealers; insurance agents, barristers and attorneys, physicians and surgeons, dentists, news press and printing establishments...” [93]

The first issue of the Manitoba Free Press, on 9 November 1872, declared: “the number of new buildings must be considered enormous.” [94] As a result of this building boom, lumber prices shot up such that “in the spring of ’71 rough lumber sold at $70 per thousand [board feet], and poor lumber it was at that; dressed lumber was $100 per thousand.” [95] The clang of hammers echoed across the town day and night. In 1880, over four hundred buildings were erected at a cost of $1 million. Seven hundred more were built the next year, worth $2.4 million, to accommodate a population of over six thousand. [96] Between 30 and 40 million board feet of wood and 220 thousand cords of firewood and lath were cut in five Manitoba districts in 1881. [97] This phenomenal volume was in addition to massive imports of lumber from the United States. Imports would continue to be the main source of Manitoba’s lumber for the next few decades. [98]

For all of the building going on, living quarters for the rising population became scarce. As a short-term solution in the spring of 1882, trains brought in 1,500 tents and seven carloads of “ready-made houses in sections” to ease the crisis. [99] For a short time Winnipeg became a tent city, but the boom was not to last. The bubble burst in the summer of 1882 and speculators moved westward. [100] Ten years after the price of lumber had risen to $100 per thousand board feet, it dropped to between $30 and $40. [101]

The total amount of wood cut during the seventy years of the settlement’s expansion is almost impossible to estimate, but the pace of its use could have been slowed through sensible forest management. Instead, enthusiastic woodcutting led to almost complete local deforestation. Taking all uses into account, I estimate that in the early years, people consumed several hundred board feet per capita annually. It is not unreasonable to suppose that number to be a thousand board feet or more by the 1880s.

Shifts in forest management practices coincided with political turning points. Before 1835, settlers sought wood where they could find it without encumbering regulations. From 1835 to 1870, the governing Council of Assiniboia regulated both timber cutting and the setting of fires and, in 1859, they prohibited tree harvesting on unoccupied lots along the Assiniboine River. [102] Surviving court records from that time show only three disputes over timber cutting. [103] So few cases might mean that disputes were generally settled out of court, that people observed the regulations, or that there was little monitoring of timber cutting. In all likelihood, the truth is the result of a combination of things.

During the 1870s, settlement spread from a narrow strip along the Red and Assiniboine rivers to 50,000 sq. km (19,300 sq. mi.) of southern Manitoba. [104] Surveyors described much of this area as “prairie and meadow land.” [105] A young emigrant agreed: “poplar and a few oaks are the only trees here.” [106] Since many new farms lacked trees, the government felt obliged to allocate woodlots, though this plan proved contentious. [107] Ideally, each settler could obtain a free woodlot of 4-8 ha (10-20 ac.) on Crown land; later, lots were available for a small fee. Alternatively, if they obtained a permit, they could cut a certain amount of timber on Crown land for their own use. However, some settlers found it difficult to obtain either woodlots or permits. On February 17, 1872, the Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba, the Queen’s representative in the province, insisted that the “woods be maintained for settlers ...” The Privy Council agreed, stating that the government would meet these provisions in the forthcoming Dominion Lands Act under which the Canadian government took over forest management in the region. [108]

The Act offered a 65 ha (160 ac.) homestead to anyone who would break the land and live on it for at least six months a year for three years. [109] Through its various amendments the Act allocated timber and firewood to settlers who had no wood on their property, granted licences and permits to commercial timber operators, and levied fines for unlawfully cutting on government land. [110] Government documents refer to permits for settlers in 1872 and later. [111] In a Privy Council report from 1875 such permits are discussed. The government authorized the local Federal Land Agent to allow settlers to cut, free of charge, all the firewood and building timber for their own needs in the vicinity of their homesteads. The report details the modest royalty required from those wishing to cut timber to sell. [112]

Some dishonest settlers cut timber on Crown land without authorization. [113] In the words of William Pearce, “In the early days it was quite common if you met a settler with a load of wood and asked him where he obtained it, he would reply on Section 37. This meant in practice that he had stolen it.” Pearce went on: “The principle of permits, as administered, was a disastrous one ... Parties went in, cut and slashed, taking out only the very best timber because they feared someone else would take it if they did not ... The administration was lax in that respect.” [114] This kind of selfish cut-and-run tactic without thought of the needs of others amounts to a “tragedy of the commons.” [115]

Several years later, protests by the Lieutenant-Governor and Manitoba members of Parliament forced the government to postpone a planned public auction of woodlots in the newly settled areas, arguing that many homesteaders could not afford them. In the end, the government yielded and reserved free woodlots for homesteaders. [116]

The Department of Interior was responsible for allocating commercial timberlands by long-term lease or annual permit while retaining ownership of the land. It originallyset the maximum size of Licensed Timber Berths at 130 sq. km (50 sq. mi.), though records show that several berths were larger. [117] Berths were leased for twenty-one years, renewable. Each lessee paid a nominal annual “ground rent” of $2 per 2.6 sq. km (sq. mi.) plus an initial bonus of $20 per 2.6 sq. km (1 sq. mi.). The government also charged a five percent royalty on the value of timber sawn. [118] As immigrants poured into Manitoba in the 1870s and early 1880s, the number of timber leases granted rose from a handful to more than twenty in 1881.

Regulations stipulated that a lessee must erect a sawmill capable of cutting one thousand board feet per day for each 6.5 sq. km (2.5 sq. mi.) of berth. A typical berth thus needed a sawmill with a capacity of 20,000 board feet per day. Lessees were to keep their mills running for six months each year throughout the term of the lease. In 1876, the government began issuing yearly permits that allowed cutting of timber for a fee based on the diameter of the stumps cut. [119]

Clear-cutting seemed the norm with no provision for forest regeneration although both federal and provincial governments did encourage tree planting. An1876 amendment to the Dominion Lands Act stated that anyone could gain title to 65 ha (160 ac.) if they planted trees, while Manitoba encouraged tree planting along “highways and elsewhere in this Province.” Setting fire to standing or fallen timber was also prohibited. [120]

The hindsight of over a century enables us to appraise how effectively the Red River Settlement and its successor, the Canadian Government, managed their forest resources. The apparent aim of both was to ensure the availability of wood for expanding settlements rather than to sustain the resources in the region. [121] At that time, officials knew little about forest productivity, an essential ingredient in estimating the amount of cutting that should be allowed. Science-based forestry did not begin in North America until the 1880s.

At first, the Canadian government made no forest inventories, had few rules for allocating leases and permits, and did little to regulate timber harvesting. Most timber leases were not surveyed in advance; licensees were expected to conduct their own. Leases were supposedly allocated through sealed tender or at public auction, but at times officials seemed to favour applicants with political connections. [122] Moreover, the harvesting fees were modest—between $20 and $40 per thousand board feet in the 1880s. [123] While the regulations of the Dominion Lands Act may have been well intentioned, the government failed to enforce them. Prior to 1879, no government timber agent was available in Winnipeg to inspect logging sites or levy fines. [124] Forest fire protection was organized by the government in 1885, but replanting of cut-over areas did not begin until the 1900s. [125]

With some exceptions, the effects of wood use at Red River on society and the environment were less dramatic when the population was small. People gathered their own firewood, a chore that took time and effort, although most building logs were brought from a distance. [126] As time went on, disparities in wealth grew as manufacturing and trade developed resulting in a more stratified society. [127] Improved transportation broadened the gap between rich and poor. Whereas steamboats could bring in expensive foods and other luxuries, poorer farmers and traders could not afford them. The livelihood of many Métis was tied to the bison hunt and the Red River cart trade, both of which all but disappeared by the 1870s. [128]

The wood economy changed with the times. Wood became a commodity as lumber firms sprang up in the 1860s and 1870s. As fiscal disparities grew, the wealthy built expensive houses trimmed with oak and walnut, decorated with imported furnishings. They could afford to heat their homes and cook their food with expensive stoves and costly firewood. Access to wood, especially quality wood, became more and more a matter of one’s ability to pay.

The pace of deforestation is depicted through numerous paintings and photographs. A famous scene painted by Peter Rindesbacher in 1821 shows the winter landscape at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers with only a few scattered trees. [129] Explorer William Keating noted that timber was already scarce when he visited the Settlement in 1823. [130] As decades wore on, local forests continued to shrink and by 1858 Alexander Ross wrote that the “best part of the settlement was treeless.” [131] Photographs by Humphrey Hime in that year show bare riverbanks with trees in the distance. Local deforestation was almost complete. [132] Photographs taken in the 1870s and 1880s show bare riverbanks with clumps of wooden buildings set in empty prairie. [133] By century’s end, many thousands of mature trees in eastern Manitoba were gone, including virtually all the white and red pines.

Could the settlers have used techniques such as coppicing and pollarding in southern Manitoba to better manage their forest resources? Coppicing and pollarding trees and tall shrubs had long been used in Scotland and elsewhere in Europe. Both had been practiced in the Highlands since at least the 1700s, following the almost complete deforestation of Scotland in previous centuries. [134] In coppicing, shrubs and immature trees are cut near the ground every few years and left to grow again. Pollarding involves removing branches 2.5-3.5 m (8-12 ft.) above the ground to produce more branches. Both techniques help ensure a supply of saplings and branches for building and fuel. [135]

Fast-growing trees and shrubs suitable for coppicing and pollarding, such as poplar and willow, grew along the Red and other rivers, around marshes, and on the open prairie. Poplars are well known to produce sucker shoots when cut or burned and rapidly grow from stumps. [136] In his 1902 textbook on forestry for Minnesota students, Samuel B. Greendiscusses the coppicing of willows, poplars, oaks, and maples for firewood and the pollarding of willows and poplars to produce branches for firewood, basketry, and other crafts. [137] At least a few settlers must have known about these techniques from their native Scotland. [138] Such management may not have prevented deforestation at Red River, but could have slowed it. [139]

Settlers elsewhere on the eastern prairies shared the problems facing the people at Red River during the pre-railway era. For instance, Fort Snelling, near the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers, suffered a lack of building timber and firewood as early as 1826. [140] The village of Minneapolis grew so fast in the 1850s that it outstripped its lumber supplies.

Early communities could cope with wood scarcity in four ways: (1) spend more time, effort, and money to obtain wood; (2) reduce demand through conservation; (3) better manage available supply; or (4) substitute another type of resource.

The Red River settlers relied mainly on the first option, although they did insulate their homes to conserve fuel. Some prairie pioneers in Canada and the United States coped with wood scarcity by building houses of sod and burning almost anything at hand—buffalo chips, corn stalks, hay, or wild grasses. [141]

Sadly, it seems no European-style wood management was practised anywhere on the eastern prairies. Given that many settlers struggled to eke out a living, one can only assume that the benefits of cutting and using whatever wood was available outweighed any thoughts of careful management. Wood for building and fuel was viewed simply as a commodity. Forest conservation had to wait several generations, but eventually the long-term effects of deforestation within the Settlement were erased as much of the local forest grew back on its own or through tree planting.

Unfortunately, logging and deforestation for agriculture continue at a rapid pace around the globe. [142] Removing trees on a massive scale leads to a warmer climate as the uptake of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide is reduced. As societies begin to take note of this threat, there is hope that people will find new ways to increase both food and energy supplies by linking agriculture and forestry. It does not have to be crops or firewood, it can be crops and firewood. [143]

I dedicate this paper to the memory of Frank H. Kaufert, former dean of the College of Forestry at the University of Minnesota, and one of the founders of the Forest History Society. I thank Nathan Kramer for archival research and am especially indebted to Jennifer Shay, Cole Wilson, and Bev Hauptmann for research and editing. To Moti Shojania, Dean of St. Paul’s College, my appreciation for providing research space. I thank Dave Raynard (former Director of Forestry, Province of Manitoba), Katherine Pettipas (former Curator of Native Ethnology at the Manitoba Museum), and Karen Nicholson (Manitoba Historic Resources Branch) for their suggestions and comments. Thanks to Michael Doig and Tim Swanson (Eastern Region, Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship), Lee Frelich (University of Minnesota Center for Forest Ecology), and Chris Kotecki (Archives of Manitoba) for valuable information. I am grateful to Dale Gibson for comments about the Council of Assiniboia court records. I also thank Scott Wilson (Consultant Forester and Forest Ecologist, Aberdeen), Fiona Watson (Centre for History, University of the Highlands and Islands, Inverness), David Foster (Harvard Forest), Alan R. Ek (Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota), Don Dickmann (Department of Forestry, Michigan State University), Alan Taylor (Department of History, University of California Davis), Mark Krawczyk (Keyline, Vermont), and Charles Mann (Amherst, Massachusetts) for their comments on coppicing and forest management. Finally, I appreciate the efforts of the editor and the helpful comments by two reviewers.

1. J. M. Bumsted, The Collected Writings of Lord Selkirk, 1810-1820, Vol. II, Winnipeg: Manitoba Record Society Publications, 1987, xiv, page 9.

2. W. L. Morton, Manitoba: A History, 2nd ed., Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1967, page 46.

3. K. G. Davies, Letters From Hudson Bay, 1703-40, London: Hudson’s Bay Record Society, 1965, pages 167-170.

4. W. L. Morton, Manitoba: A History, 2nd ed., page 65.

5. A. Ross, The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress, and Present State, with Some Account of the Native Races and its General History to the Present Day, London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1858; Reprinted Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1972, page 170-171.

6. Edward Van Dyke Robinson, “Early Economic Conditions and the Development of Agriculture in Minnesota,” in The University of Minnesota Studies in the Social Sciences No. 3, Minneapolis: Bulletin of the University of Minnesota, 1915, page 32.

7. J. Macoun, Manitoba and the Great North-West, Guelph: The World Publishing Company, 1882, page 489; Alan F. J. Artibise, Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth, 1874-1914, Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1975.

8. Plant communities within 30 km (18 miles) of the centre of the Settlement calculated from maps in E. F. Bossenmaier and C. G. Vogel, Wildlife and Wildlife Habitat in the Winnipeg Region, Winnipeg: Resource Planning, Manitoba Department of Mines, Resources, and Environmental Management, 1974, pages 8-12.

9. Thomas R. Weir, Economic Atlas of Manitoba, Winnipeg: Department of Industry and Commerce, Province of Manitoba, 1960, pages 20-21.

10. Chester Martin, Red River Settlement Papers in the Canadian Archives Relating to the Pioneers, (Ottawa: Archives Branch, 1910), 22. The term “pine” in McDonell’s description may refer to more than one type of conifer.

11. J. Warkentin and R. I. Ruggles, Historical Atlas of Manitoba, Winnipeg: The Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba, 1970, page 189 (Map 74).

12. C. T. Shay, “The History of Manitoba’s Vegetation,” pp. 93-125 in Natural Heritage of Manitoba: Legacy of the Ice Age, edited by J. T. Teller, Winnipeg: Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature, 1984, pages 108-109; J. M. Shay, The Vegetation of Significant Natural Areas in Winnipeg, Winnipeg: Department of Botany, University of Manitoba, 1996, page 71; Jennifer M. Shay and Isobel Waters, A Botanical Study of the Forest Communities Along the LaSalle River in St. Norbert, Manitoba, Winnipeg: Department of Botany, University of Manitoba, 1995, pages 54-55.

13. This is the area between the U.S. border and the Winnipeg River and from the Red River to the Ontario border.

14. Manitoba Forest Service, Report No. 1: Southeastern Forest Section, Forest Resources Inventory; Manitoba Forest Service, Report No. 2: Winnipeg River Forest Section, Forest Resources Inventory; Manitoba Forest Service, Report No. 3: Lowlands South Forest Section, Forest Resources Inventory; Surveyor’s descriptions of the vegetation during the land surveys of the late 1800s and early 1900s are contained in Office of the Surveyor General, Extracts on Reports from Townships East of the Principal Meridian received from surveyors to July 1, 1914, Ottawa: Topographical Surveys Branch, Dept. Of the Interior, 1915, pages 8-43; S. M. Anderson, An Investigation of Soil/Vegetation Relationships in Southeastern Manitoba, Winnipeg: MSc. Thesis, University of Manitoba, 1960; for forest descriptions contained in soils reports see R. E. Smith, W. A. Ehrlich, J. S. Jameson, J. H. Cayford, Report of the Soil Survey of the South-Eastern Map Sheet Area, Winnipeg: Manitoba Dept. Of Agriculture and Conservation, 1964, pages 94-104; R. E. Smith, W. A. Ehrlich, S. C. Zoltai, Soils of the Lac du Bonnet Area, Winnipeg: Manitoba Department of Agriculture, 1967, pages 102-111.

15. For estimating the amount of lumber needed for an average house, see Thomas Spence, Useful and practical hints for the settler on Canadian prairie lands and for the guidance of intending British emigrants to Manitoba and the North-West of Canada with facts regarding the soil, climate, products, etc., and the superior attractions and advantages possessed, in comparison with the western prairie states of America, St. Boniface: Second edition, revised and corrected, Office of the Minister of Agriculture, 1881, pages 17; J. I. Rempel, Building With Wood, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1967, page 75.

16. Department of the Environment, Canada Land Inventory. Land Capability for Forestry Manitoba, South Part, map.

17. John McDougall, Forest, Lake and Prairie – Twenty Years of Frontier Life in Western Canada, 1842-1862, Toronto: The Ryerson Press, 1895, pages 104-105.

18. W. Douglas, “New Light on the Old Forts of Winnipeg,” in Manitoba Historical Society Transactions Series 3, accessed 13 April 2009, no pages given.

19. Samuel Taylor, Archives of Manitoba, MG 2 C13 Samuel Taylor’s Journal 1853-1857, 4.

20. George Young, Manitoba Memories: Leaves From My Life in the Prairie Province, 1868-1884, Toronto: William Briggs, 1897, page 74.

21. Library and Archives Canada, John Inkster at Fort Garry, 1840-1872 Fonds, R7918-0-9-E, “John Inkster Account Book 1848-1852,” 19. Former archival reference no. MG19-E7.

22. Map in K. Wilson, “Life at Red River: 1830-1860,” Ginn Studies in Canadian History, Toronto: Ginn and Company, 1970, page 8; Farmsteads were distributed 56 km (37 miles) upstream and 32 km (20 miles) downstream along the Red River. Settlers, mostly Métis, were scattered 64 km (40 miles) upstream along the Assiniboine; A. Ross, The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress, and Present State, with Some Account of the Native Races and its General History to the Present Day, page 388; J. Wade, Red River Architecture, 1812-1870, MA Thesis, University of British Columbia, 1967, page 11.

23. Robert Coutts, Road to the Rapids: the Nineteenth-Century Church and Society at St. Andrew’s Parish, Red River, Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2000, page 143.

24. J. Wade, Red River Architecture, 1812-1870, page 11.

25. R. Blakeley, “Opening of the Red River of the North to Commerce and Civilization,” in Minnesota Historical Society Collections, vol. 8, pages 45-67, St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1898, page 64; C. H. Lee, The Long Ago. Facts of History from the Writings of Captain Alexander Henry, Hon. Charles Cavalier, H. V. Arnold, Colonel C. A. Lounsberry and Others, Walhalla: Semi-weekly Mountaineer Print, 1898, page 39; John H. O’Donnell, Manitoba as I saw it, from 1869 to Date. With Flashlights on the First Riel Rebellion, Toronto: The Musson Book Company Limited, 1909, page 106, accessed 29 April 2009.

26. R. G. MacBeth, The Making of the Canadian West: The Reminiscences of an Eye-Witness, Toronto: W. Briggs, 1905, page 33.

27. Robert Coutts, Road to the Rapids: the Nineteenth-Century Church and Society at St. Andrew’s Parish, Red River, page 143; W. J. Healy, Winnipeg’s Early Days, Winnipeg: Stovel Company, Ltd., 1923, page 97.

28. Archives of Manitoba, George Henry Gunn Fonds, Journal of Peter Garrioch Part 5: Home Journal, 1845-1847, MG9 A78-3 box 6 file 6.

29. A. Ross, The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress, and Present State, with Some Account of the Native Races and its General History to the Present Day, page 198; Leo Pettipas, personal communication.

30. Alan F. J. Artibise, ed., Gateway City: Documents on the City of Winnipeg, 1873-1913, Vol. 5 of the Manitoba Record Society, Winnipeg: Manitoba Record Society, 1979, page 5; R. Bérard, Rivière aux Rats Canoe Route (map brochure), Winnipeg: Manitoba Department of Tourism, Recreation, and Cultural Affairs, Parks Branch, circa 1970, map.

31. Historic Resources Branch, The Lumber Industry in Manitoba, Winnipeg: Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Tourism, 2000, page 21, accessed 16 May 2014.

32. W. J. Healy, Winnipeg’s Early Days, page 70; R. G. MacBeth, The Making of the Canadian West: The Reminiscences of an Eye-Witness, page 98.

33. A. W. Bealer, Old Ways of Working Wood (Edison: Castle Books, 1996), 87.

34. George Sturt, The Wheelwright’s Shop (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1963), 34.

35. J. Wade, Red River Architecture, 1812-1870, 11; George Young, Manitoba Memories: Leaves From My Life in the Prairie Province, 1868-1884, 198.

36. Grant MacEwan, Cornerstone Colony: Selkirk’s Contribution to the Canadian West (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1977), 177.

37. W. Douglas, “New Light on the Old Forts of Winnipeg”; Edmund Henry Oliver, The Canadian North-West: Its Early Development and Legislative Records. Minutes of the Councils of the Red River Colony and the Northern Department of Rupert’s Land Vol. 2 (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1915), 1290.

38. J. Wade, Red River Architecture, 1812-1870, ii, 6, 46.

39. Eric Sloane, Museum of Early American Tools (New York: Ballantine Books, 1974), 15.

40. John E. Foster, “Ruperts’ Land and the Red River Settlement,” pages 19-72 of The Prairie West to 1905: A Canadian Sourcebook, edited by Lewis G. Thomas (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1975), 43-44.

41. Thomas Spence, Useful and practical hints for the settler on Canadian prairie lands and for the guidance of intending British emigrants to Manitoba and the North-West of Canada with facts regarding the soil, climate, products, etc., and the superior attractions and advantages possessed, in comparison with the western prairie states of America, 17; J. I. Rempel, Building With Wood, 75.

42. A. Ross, The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress, and Present State, with Some Account of the Native Races and its General History to the Present Day, 388.

43. John E. Foster, “Ruperts’ Land and the Red River Settlement,” 43-45.

44. J. Wade, Red River Architecture, 1812-1870, 27; drawings of some surviving houses can be found in Lillian Gibbons and Arlene Osen, Stories Houses Tell (Winnipeg: Hyperion Press, 1978), 18, 22, 26.

45. Lillian Gibbons, “Early Red River Homes,” MHS Transactions, Series 3 (Winnipeg: Manitoba Historical Society, 1945-46), no pages given. Accessed 28 May 2009 at http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/transactions/3/redriverhomes.shtml

46. Archives of Manitoba, B235.

47. A. Ross, The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress, and Present State, with Some Account of the Native Races and its General History to the Present Day, page 388; D. King, The Grey Nuns and the Red River Settlement (Agincourt: The Book Society of Canada Limited, 1980), 36.

48. W. J. Healy, Winnipeg’s Early Days, page 91.

49. Wooden artifacts, wood chips, shavings, and charcoal fragments were identified by J. Zwiazek, Department of Botany, University of Manitoba. These fragments were from diverse contexts and ranged in size from a few millimetres to 1 metre. For wood identification, thin-sections were cut by hand in transverse, tangential, and/or radial planes. They were stained in saffranin and examined under a Zeiss compound microscope (SN4257342) with magnifications up to 1000 times. Thin-sections are necessary to distinguish between poplar and willow, and among the conifers. Charcoal pieces (usually greater than 1-2 millimetre transverse face) were mounted on microscope slides with plasticine and examined under a Zeiss universal research microscope with a reflected light attachment. The sources of information for Table 3 are: Scott St. George and Erik Nielsen, “Paleoflood Records for the Red River, Manitoba, Canada Derived from Anatomical Tree-Ring Signatures,” in The Holocene 13, pages 547-555 (2003), page 549; Sid Kroker, Barry B. Greco, Sharon Thomson, 1990 Investigations at Fort Gibraltar I, Winnipeg: The Forks Public Archaeology Project, 1991, page 140; K. David McLeod, Archaeological Investigations at Delorme House (Dklg-18),1981, Final Report 13, Winnipeg: Department of Cultural Affairs and Historical Resources, 1982, page 107; K. David McLeod, editor, The Garden Site, Dklg-16. A Historical and Archaeological Study of a Nineteenth Century Métis Farmstead, Final Report 16, Winnipeg: Department of Cultural Affairs and Historical Resources, 1983, page 109; Peter J. Priess, Sheila Bradford, S. Biron Ebell, Peter W. Nieuwhof, Archaeology at The Forks: An Initial Assessment, Microfiche Report Series No. 375, Ottawa: Environment Canada, Canadian Parks Service, 1986, page 405; Patricia M. Badertscher, “Salvage Operations at Dllg-13, a Scots Métis Farmstead in the Red River Settlement,” Manitoba Archaeological Quarterly 8 (1984), page 11; C. Thomas Shay, Margaret Kapinga, Jennifer M. Shay, “The Analysis of Plant and Other Organic Remains from Upper Fort Garry (1846-1882),” presented to the Manitoba Heritage Federation, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Department of Anthropology, 2002, Table 3. The dates of the sites apart from Fort Gibraltar are from Bonnie Lee A. Brenner and Gregory G. Monks, “Detecting Economic Variability in the Red River Settlement” Historical Archaeology 36 (2002), page 26.

50. Pine is listed in the Hudson’s Bay Company inventories as an important building material, but it made up only 9% of the archaeological wood. Spruce is not mentioned in the inventories, yet made up half of the wood remains.

51. Russell M. Burns and Barbara H. Honkala, Silvics of North America, Washington: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1990, pages 594-595.

52. Donald Culross Peattie, A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America, New York: Bonanza Books, 1966, page 386; Aldren A. Watson, Country Furniture, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1974, page 36.

53. Anne Matheson Henderson, Kildonan on the Red, Winnipeg: Lord Selkirk Association of Rupert’s Land, 1981, page 35.

54. W. Douglas, “New Light on the Old Forts of Winnipeg.”

55. Edmund Henry Oliver, The Canadian North-West: Its Early Development and Legislative Records. Minutes of the Councils of the Red River Colony and the Northern Department of Rupert’s Land, Vol. 1, Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1914, pages 406-407, 432-434; Samuel B. Steele, Forty Years in Canada: Reminiscences of the Great North-West With Some Account of His Service in South Africa, Toronto: Coles, 1915, page 31.

56. A. Ross, The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress, and Present State, with Some Account of the Native Races and its General History to the Present Day, page 394; J. Wade, Red River Architecture, 1812-1870, page 51.

57. Robert Coutts, Road to the Rapids: the Nineteenth-Century Church and Society at St. Andrew’s Parish, Red River, 122.

58. This range of wood use is based upon three estimates. In Hiram M. Drache, The Challenge of the Prairie: Life and Times of Red River Pioneers (Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1970, page 111), Drache states that in Georgetown on the Red River near Moorhead, Minnesota, an average home used at least 15 cords over a winter. The 1881 Census for Manitoba gives a range of 6-32 cords per family per year for the five census districts with an average of 16 cords (Government of Canada, 1882, Table 26). H. S. Graves, The Use of Wood for Fuel. Bulletin No. 753, Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture, 1919), Table 1 gives a range of 3-19 cords and an average of 11.6 cords for all US farm households in 1917 at a time when some coal was also used for fuel; H. Y. Hind, Papers Relative to the Exploration of the Country Between Lake Superior and the Red River Settlement, London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1859, page 107.

59. Michael Harris, Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Heating with Wood, 1st edition, Secaucus: The Citadel Press, 1980, page 24.

60. H. Y. Hind, Narrative of the Canadian Red River exploring expedition of 1857 and of the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan exploring expedition of 1858, London: Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts, 1860; Second printing, Edmonton: M. G. Hurtig Ltd., 1971, page 231.

61. Robert Michael Ballantyne, Hudson’s Bay, or, Every-day Life in the Wilds of North America During Six Years’ Residence in the Territories of the Hon. Hudson’s Bay Company, Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1859, page 86.

62. Diane Payment, Riel Family: Home and Lifestyle at St. Vital, 1860-1910, Winnipeg: Parks Canada, Historical Research Division, Prairie Region, 1980, pages 18-19.

63. E. J. Mullins and T. S. McKnight, Canadian Woods: Their Properties and Uses, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981, Table 5.4, page 123.

64. C. T. Shay, “Aspects of Ethnobotany in the Red River Settlement in the Late 19th Century,” pp. 365-370 in Status, Structure, and Stratification: Current Archaeological Reconstructions, edited by M. K. Thompson, M. T. Garcia, F. J. Kense, Calgary: University of Calgary Archaeological Association, 1985, page 369.

65. J. Wade, Red River Architecture, 1812-1870, pages 50-51.

66. Gordon Moat, “Canada Stoves in Rupert’s Land,” The Beaver, Winter 1979, page 54; R. V. Reynolds and A. H. Pierson, Fuel Wood Used in the United States, 1630-1930, Washington: US Department of Agriculture, 1942, page 3.

67. Edmund Henry Oliver, The Canadian North-West: Its Early Development and Legislative Records. Minutes of the Councils of the Red River Colony and the Northern Department of Rupert’s Land Vol. 1, page 318.

68. Anne Matheson Henderson, Kildonan on the Red, page 36.

69. Virginia Petch, “Salt-Making in Manitoba,” Manitoba History, Number 51, 2006, accessed 23 May, 2014; Edith Paterson, Tales of Early Manitoba from the Winnipeg Free Press, Winnipeg, Manitoba: Winnipeg Free Press, 1978, page 31.

70. Anne Matheson Henderson, Kildonan on the Red, 24; Canon E. K. Matheson, “Chapters in the North-West History Prior to 1890, Related by Old Timers, Saskatchewan’s First Graduate. Being a History of the Development of the Church of England in North-Western Saskatchewan. Battleford, Saskatchewan.” in Canadian North-West Historical Society Publications 1, no. 3 (1927), page 7.

71. Eric John Holmyard, Makers of Chemistry, Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1931, pages 245-246.

72. Edwin C. Guillet, Pioneer Arts and Crafts, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1968, page 42.

73. Edwin C. Guillet, The Pioneer Farmer and Backwoodsman, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1963, page 206.

74. Conner Prairie, Fuel for the Fires: Charcoal Making in the Nineteenth Century (1996), no pages given, accessed 28 May 2009.

75. Ibid.

76. Frank Garrod and Louis Lafleche, Lower Fort Garry Smithy: Charcoal, Coal, and Slag Analysis, Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1985, page 8.

77. Edmund Henry Oliver, The Canadian North-West: Its Early Development and Legislative Records. Minutes of the Councils of the Red River Colony and the Northern Department of Rupert’s Land, Vol. 1, page 453; H. Y. Hind, Narrative of the Canadian Red River exploring expedition of 1857 and of the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan exploring expedition of 1858, page 187; Stanley Norman Murray, The Valley Comes of Age: A History of Agriculture in the Valley of the Red River of the North, 1812-1920, Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1967, page 39.

78. Rebuilt from an earlier vessel, she had a capacity of 50 to 75 tons, a 100-horsepower locomotive-type steam engine, was 27 m (90 ft) long, 6.7 m (22 ft) wide, but drew only 36 cm (14 in) of water. W. L. Morton, Manitoba: A History, 2nd ed., pages 101, 115, 193-195.

79. Steamers also journeyed between Winnipeg and Edmonton, Alberta by way of Lake Winnipeg and the Saskatchewan River. J. Macoun, Manitoba and the Great North-West, page 502; D. S. Lileboe, Steam Navigation on the Red River of the North 1859-1881, Master’s Dissertation, University of North Dakota, 1977, page 100.

80. Fred A. Bill and J. W. Riggs, Life on the Red River of the North, Baltimore: Wirth Brothers, 1947, page 74; “Steamboats On The Red,” no date, Pluck 1878-1886, accessed 7 July 2014.

81. Erik F. Haites, James Mak, Gary M. Walton, Western River Transportation: the Era of Early Internal Development, 1810-1860, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975, page 56, estimates the daily consumption at one cordwood for each eight tons of steamboat, for a 100-ton steamboat this meant 12.5 cords a day; M. McFadden, “Steamboating on the Red,” in Manitoba Historical Society Transactions Series 3 (1950-51), no pages given, accessed online 28 May 2009; David E. Schab, “Woodhawks and Cordwood: Steamboat Fuel on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, 1820-1860,” Journal of Forest History, 21 (July 1977), page 129.

82. Clarence A. Glasrud, Roy Johnson’s Red River Valley: A Selection of Historical Articles First Printed in the Forum from 1941 to 1962, Moorhead: Red River Valley Historical Society, 1982, pages 157, 238.

83. Eric Wells, Winnipeg, Where the New West Begins: An Illustrated History, Burlington, Ontario: Windsor Publications (Canada) Ltd., 1982, page 121.

84. Thomas R. Weir, Economic Atlas of Manitoba, page 28.

85. Library and Archives Canada, Privy Council Office, RG 2, “Timber limit, west of Whitemouth River – [Minister of the Interior], 28/12/78, [recommends] lease to Jos. Whitehead, contractor for section 15, [Canadian Pacific Railway],” Series A-1-a, for Order in Council see volume 374, Reel C-3324, Access Code 90, see also 1879-1110, Series A-1-d, Volume 2758; Library and Archives Canada, Privy Council Office, RG 2, “Timber limits on Whitemouth River – [Minister of Interior], 23 July/79, [recommends] a license be issued to Jos. Whitehead of Order-in-Council Number: 1879-1110,” Series A-1-a, for Order in Council see volume 381, Reel C-3326, Access Code 90, amended by Order in Council 1880-1224, 1880/07/05; see also 1880-1224; see also 1878-1110, Series A-1-d, Volume 2760; Historic Resources Branch, The Lumber Industry in Manitoba, page 27.

86. Formulae for converting logs to board feet in T. Eugene Avery, Forest Measurements, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1967, page 51. The dimensions specified for the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railroad in 1884 are based on Robert Gordon, James Robert Mosse, Granville C. Cuningham, Railway Construction and Working, with an Abstract of the Discussion Upon the Papers, London: Institute of Civil Engineers, 1886, page 112 (electronic version at AlanMacek.com).

87. C. B. Gill, Manitoba Forest History, Winnipeg: Forest Service, Department of Mines and Natural Resources, 1962, page 19.

88. Deborah Welch, T. A. Burrows, 1857-1929: Case Study of a Manitoba Businessman and Politician, Winnipeg: MA Thesis, University of Manitoba, 1983, page 17; C. B. Gill, Forest Resources Inventory, pages 1, 2, 3, 6, 10, Winnipeg: Forest Service, Department of Mines and Natural Resources, 1956.

89. Department of Interior, Annual Report Vol. 10, Canada Parliament Sessional Papers No. 25, Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1883.

90. W. L. Morton, Manitoba: A History, 2nd ed., page 175.

91. Thomas R. Weir, Economic Atlas of Manitoba, page 29; J. Warkentin and R. I. Ruggles, Historical Atlas of Manitoba, pages 319, 321, 323.

92. J. Macoun, Manitoba and the Great North-West, page 490; J. H. Ellis, The Ministry of Agriculture in Manitoba, 1870-1970, Winnipeg: Manitoba Department of Agriculture, 1971, page 50.

93. J. H. Ellis, The Ministry of Agriculture in Manitoba, 1870-1970, page 617.

94. Edith Paterson, Tales of Early Manitoba from the Winnipeg Free Press, page 70.

95. George Bryce, “Early Days in Winnipeg,” in Manitoba Historical Society Transactions Series 1 No. 46, accessed 29 April 2009.

96. J. Macoun, Manitoba and the Great North-West, page 500; Alan F. J. Artibise, Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth, 1874-1914, page 130; J. H. Ellis, The Ministry of Agriculture in Manitoba, 1870-1970, page 41.

97. Government of Canada, Census of Canada, 1880-81, Vol. 3, Ottawa: MacLean, Roger & Co., 1882, pages 264-265 (Table 26).

98. Historic Resources Branch, The Lumber Industry in Manitoba, page 19.

99. Fred C. Lucas, An Historical Souvenir Diary of the City of Winnipeg, Canada, Winnipeg: Cartwright and Lucas, 1923, pages 57, 68.

100. Charles N. Bell, “The Great Winnipeg Boom,” Manitoba History, Number 53, 2006, accessed 3 May, 2015; R. R. Rostecki, The Growth of Winnipeg, 1870-1886, MA Thesis, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 1980; Christopher Dafoe, Winnipeg: Heart of the Continent, Winnipeg: Great Plains Publications, 1998, page 73.

101. George Bryce, Early Days in Winnipeg, Winnipeg: Manitoba Free Press Printers, 1894, page 5, accessed 16 May 2014 at peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/2127.html; Historic Resources Branch, The Lumber Industry in Manitoba, page 19.

102. Edmund Henry Oliver, The Canadian North-West: Its Early Development and Legislative Records. Minutes of the Councils of the Red River Colony and the Northern Department of Rupert’s Land, Vol. 1, pages 263, 264, 274, 369, 373, 440-443 485-486; and Vol. 2, page 1318.

103. Archives of Manitoba, General Quarterly Court Records, Council of Assiniboia, MG2 B4-1.

104. Thomas R. Weir, Economic Atlas of Manitoba, page 29 (Plate 13).

105. J. Warkentin and R. I. Ruggles, Historical Atlas of Manitoba, page 323 (Map 146).

106. Ronald A. Wells, Letters From a Young Emigrant in Manitoba, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1981, page 95.

107. J. H. Ellis, C. B. Gill, F. W. Brodrick, Farm Forestry and Tree Culture Projects for the Non-forested Region of Manitoba, Winnipeg: Advisory Committee on Woodlots and Shelterbelts, Government of Manitoba, 1945, page 108.

108. Library and Archives Canada, RG 15, Headquarters Correspondence, vol. 229, file 1125, Report of a Committee of the Privy Council, 25 January 1873, Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1873.

109. “An Act Respecting the Public Lands of the Dominion, 1872” in Acts of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada, Ottawa: Brown Chamberlin, 1873, Chapter 23, pages 23-26.

110. The Act was based on The Crown Timber Act of 1849; Monique Passelac-Ross, A History of Forest Legislation in Canada: 1867-1996, Calgary: Canadian Institute of Resources Law, 1997, page 7; C. B. Gill, Manitoba Forest History, page 19.

111. “Extract from Report of Secretary of State of Canada for the year ending on the 30th June, 1872 Re: Revision for dividing timbered portions into wood lots,” in J. H. Ellis, C. B. Gill, F. W. Brodrick, Farm Forestry and Tree Culture Projects for the Non-forested Region of Manitoba, page 108.

112. The suggested royalty was twenty cents per cord of firewood, one dollar per thousand fence posts, two cents per cubic foot for oak building timber, and one cent per cubic foot for pine or other soft wood. Library and Archives Canada, RG 15, vol. 85, Ref. 3,700, P.C. 573, Report of the Privy Council, June 25, 1875, Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1875, page 325.

113. Historic Resources Branch, The Lumber Industry in Manitoba, page 7.

114. W. Pearce, Transcription of the William Pearce Manuscript, Vol. 1 Index and Chapters I and II, University of Alberta Archives Accession #74-169-459-55 (W. Pearce Collection), page 55.

115. Garrett Hardin. “The tragedy of the commons.” Science 162, no. 3859 (1968), pages 1243-1248.

116. Library and Archives Canada, RG 15, vol. 83, Orders in Council Dealing With the Department of the Interior. Memorandum; Department of Interior, Dominion Lands Office, 2 November 1874, Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1874, page 185.

117. C. B. Gill, Manitoba Forest History, page 4; Library and Archives Canada, RG 15, vols. 83-84, Orders in Council Dealing With the Department of the Interior Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1874, 1879.

118. Historic Resources Branch, The Lumber Industry in Manitoba, page 6; Library and Archives Canada, RG 15, Headquarters Correspondence, vol. 229, file 1896, Department of Secretary of State J. C. Aitkin, Report re Macaulay, Ginty and Sprague, Jan. 24, 1873, Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1873.

119. C. B. Gill, Manitoba Forest History, pages 5, 7; Library and Archives Canada, RG 15, vol. 83, Reg. No. 125, Report of the Privy Council, 17 January 1876 Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1876, page 405.

120. J. H. Ellis, C. B. Gill, F. W. Brodrick, Farm Forestry and Tree Culture Projects for the Non-forested Region of Manitoba, page 108; J. H. Ellis, The Ministry of Agriculture in Manitoba, 1870-1970, page 67.

121. R. Gillis and Thomas R. Roach, Lost Initiatives: Canada’s Forest Industries, Forest Policy, and Forest Conservation, New York: Greenwood Press, 1986, page 31.

122. R. K. Winters, The Forest and Man, New York: Vantage Press, 1974, pages 285–288; C. B. Gill, Manitoba Forest History, page 3; Historic Resources Branch, The Lumber Industry in Manitoba, page 38.

123. The 1882 price range. Historic Resources Branch, The Lumber Industry in Manitoba, page 19.

124. Library and Archives Canada, RG 15, vol. 84, Orders in Council dealing with the Department of Interior, Ref. 18,856, 25 June 1879, Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1979, page 99.

125. C. B. Gill, Manitoba Forest History, pages 10, 11.

126. J. Perlin, A Forest Journey: the Role of Wood in the Development of Civilization, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991; C. D. Risbrudt, “Wood and Society,” pages 1-5 of Handbook of Wood Chemistry and Wood Composites, ed. R. M. Rowell, Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2005, page 1.

127. Gerald Friesen, The Canadian Prairies: a History, student edition, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984, pages 91, 94, 112; Gerald Friesen, “Imports and Exports in the Manitoba Economy 1870-1890,” in Manitoba History 16 (1988), pages 31-41; D. Nerbas, “Wealth and Privilege: an Analysis of Winnipeg’s Early Business Elite,” in Manitoba History 47 (2004), pages 42-64.

128. Donald Gunn, History of Manitoba from the Earliest Settlement to 1835, Ottawa, Ontario: Roger Maclean, 1880, available as part of the Elizabeth Dafoe Library Microforms collection, 1880, page 348.

129. Painting reproduced in K. Wilson, “Life at Red River: 1830-1860,” Ginn Studies in Canadian History, 9.

130. W. H. Keating, Narrative of an Expedition to the Source of St. Peter’s River, Lake Winnipeck, Lake of the Woods, etc., Performed in the Year 1823, London: G. R. Whittaker, 1825, page 61.

131. A. Ross, The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress, and Present State, with Some Account of the Native Races and its General History to the Present Day, page 199.

132. Manitoba Historical Society, Photographs from the Provincial Archives of Manitoba, 1967, no pages given, accessed 16 May 2014; Richard J. Huyda, Camera in the Interior, 1858: H. L. Hime, Photographer, the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition, Toronto: Coach House Press, 1975.

133. Photographs in Christopher Dafoe, Winnipeg: Heart of the Continent, pages 14, 40-41, 57, 61, 66, 67, 81, 88; Eric Wells, Winnipeg, Where the New West Begins: An Illustrated History, page 103.

134. T. C. Smout, Alan R. MacDonald and Fiona Watson, A History of the Native Woodlands of Scotland, 1500-1920, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007, Chapter 7.

135. Oliver Rackham, The History of the Countryside, London: Phoenix Press, 2000, pages 65-67.

136. E. V. Peterson and N. M. Peterson, Ecology, Management and Uses of Aspen and Balsam Poplar in the Prairie Provinces. Special Report 1, Edmonton, Alberta: Forestry Canada, 1992, pages 28-35; a year’s supply of firewood would amount to 4,000 to 6,000 three- or four-inch saplings, equal to several acres of young forest. Michael Harris, Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Heating with Wood, Secaucus: The Citadel Press, 1980, page 24.

137. Samuel B. Green, Forestry in Minnesota, St. Paul: Pioneer Press Company, 1902, page 68.

138. Scott Wilson and Fiona Watson inform me that such management techniques were not always employed in Scotland during past centuries.

139. In order for coppicing to contribute to the firewood supply, householders needed a woodlot they could manage over a period of years. If we assume a 20-acre woodlot were composed mainly of aspen trees and that a few acres were harvested every year, how much firewood could they have harvested over a 20-year cycle? According to Manitoba forester Michael Doig (personal communication), in order to obtain 20 cords of firewood per year from a woodlot of aspen, households would need to clear 2 to 3 acres per year. For 30 cords, they would need 3 to 4.5 acres. If each Red River farm had a 20-acre woodlot and consumption was 20 cords per year, they could harvest 33-50% of their firewood on a sustained basis. If consumption were 30 cords a year, they could harvest between 22% and 33%.

140. Steve Hall, Fort Snelling: Colossus of the Wilderness, St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1987, page 21.

141. Everett Dick, The Sod-House Frontier, 1854-1890: A Social History of the Northern Plains from the Creation of Kansas & Nebraska to the Admission of the Dakotas, Third Printing, Lincoln: Johnsen Publishing Company, 1954, page 259; G. Riley, Frontierswomen, Ames: Iowa University Press, 1981, page 20; J. A. Swisher, “Claim and Cabin,” in The Palimpsest vol. 49, no. 7, William J. Petersen, ed., Iowa City: State Historical Society of Iowa, 1968, page 251.

142. Michael Williams, “Forests,” in The Earth as Transformed by Human Action: Global and Regional Changes in the Biosphere over the Past 300 Years, B. L. Turner, II, W. C. Clark, R. W. Kates, J. F. Richards, J. T. Mathews, W. B. Meyer, eds., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990, page 179; Michael Williams, Deforesting the Earth: from Prehistory to Global Crisis, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2003, pages 458-493.

143. Jo Smith, Bruce D. Pearce, Martin S. Wolfe, “A European Perspective for Developing Modern Multifunctional Agroforestry Systems for Sustainable Intensification,” in Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 27 (2012), 323-332; Shibu Jose, Michael A. Gold, Harold E. Garrett, “The Future of Temperate Agroforestry in the United States,” in Advances in Agroforestry (Book 9), edited by P. K. R. Nair and D. Garrity, Springer: 2012, page 217-245.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 5 February 2022