by Margaret Bertulli

Winnipeg, Manitoba

|

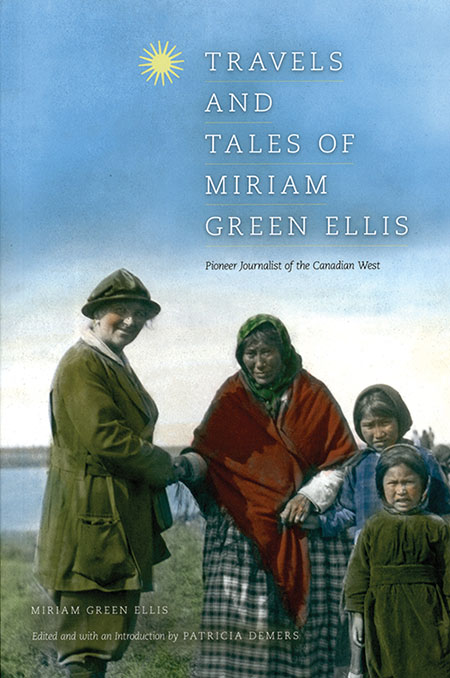

Miriam Green Ellis, Travels and Tales of Miriam Green Ellis, Pioneer Journalist of the Canadian West. Patricia Demers, ed., Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2013, 215 pages. ISBN 978-0-88864-626-2, $34.95 (paperback)

Journalist, traveller, and suffragist Miriam Green Ellis (1879-1964) comes alive again in the pages of Patricia Demers’s reconstruction of Ellis’s life through her papers and photographs housed at the Bruce Peel Special Collections Library of the University of Alberta. The book has five sections, with Ellis’s writings, both non-fiction and fiction, forming the major part. It begins with Demers’s brief bibliographic analysis of the woman, her times and her writing. The body of the book contains three chapters of Ellis’s published and unpublished works and photographs grouped into key threads of her work: travel and storytelling, the agricultural beat, and her advocacy on behalf of women and the West. The back matter contains the endnotes, bibliography and index.

Journalist, traveller, and suffragist Miriam Green Ellis (1879-1964) comes alive again in the pages of Patricia Demers’s reconstruction of Ellis’s life through her papers and photographs housed at the Bruce Peel Special Collections Library of the University of Alberta. The book has five sections, with Ellis’s writings, both non-fiction and fiction, forming the major part. It begins with Demers’s brief bibliographic analysis of the woman, her times and her writing. The body of the book contains three chapters of Ellis’s published and unpublished works and photographs grouped into key threads of her work: travel and storytelling, the agricultural beat, and her advocacy on behalf of women and the West. The back matter contains the endnotes, bibliography and index.

Demers adumbrates the major events of Ellis’s life as glimpsed through the archival record. Born in Richville, New York, Green and her Canadian parents moved to a farm in Athens, Ontario. Later she attended Bishop Strachan School in Toronto and graduated from the Toronto Conservatory of Music. In 1904, the family moved to Edmonton, and in the following year Green married George Edward Ellis, who was appointed the provincial Inspector of Schools in 1906. Three years afterwards, he resigned this position to undertake graduate studies in Chicago, where Miriam Green Ellis likely accompanied her husband. The next indication we have of her is in 1912, coaching a hockey team in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, where she also probably wrote without byline for the Prince Albert Daily Herald. In 1916, she and her husband separated, but a record of divorce does not exist.

By 1913 Ellis was a member of the Canadian Women’s Press Club (CWPC), becoming the president of the Edmonton Branch in 1919, organizing the first conference in Edmonton in 1920, and over the years holding many positions, including several terms as regional vice-president. Her 1922 trip down the Mackenzie River to Aklavik, Northwest Territories, north of the Arctic Circle, was a major accomplishment in which her keen observations of people, places, and the natural environment shine, as does her intrepid spirit of adventure. Underscoring the importance of this trip to her and to women in journalism is the fact that she was obliged to take a two-month leave from her job in order to undertake it, as her boss, editor Frank Oliver of the Edmonton Bulletin, was unwilling to authorize it. She “made her own way when the industry was unwilling to create this kind of space for a woman.” Stemming from this trip is Down North, the daily account of her perspicacious observations on northern life, with especial reference to the northern women she encountered; as well as two previously unpublished short stories, included in the book, which explore themes of racism and solitude.

Evident in Ellis’s participant approach to her duties as agricultural editor of the Family Herald and Weekly Star is her strong sympathy for prairie farm women and her intense and authentic interest in delving into the realities of the people and the time. She toured farms, reported on the rituals of cattle and grain shows and on the Hobbema Sun Dance, and shed light on the back-to-the-land movement precipitated by the Depression.

A sense of humour always stands one in good stead, and Ellis’s brand of understated humour is well referenced in the final section of her writings in an article describing the vicissitudes of driving in 1920: “... without bothering to take off the broken bumper, I started for the garage, going down a back street, as the loose ends of the bumper scraping and rattling along the ground made an infernal row. I saw a man rush out from the walk and throw up his hands, so I stopped. He told me my bumper was broken. I went on, and every man I met tried to tell me the same thing. I felt like mentioning I had suspected as much” (p. 156).

Ellis’s contemporaries and colleagues include feminist and politician Nellie McClung, agricultural journalist E. Cora Hind, and jurist and activist Emily Murphy. Ellis retired in 1953 at the age of 73 as western editor for Montreal’s Family Herald and Weekly Star, having held this position for 25 years. Demers has done a great service to historical journalism and the involvement of prairie women in the feminist movement of the early 20th century by re-awakening knowledge and interest in the life of Miriam Green Ellis, a “fantastic woman” (p. x), an “incredible Canadian” (p. xxii), and a foremost agricultural journalist in the West.

More information can be found at http://omeka.library.ualberta.ca/MGE, which includes a seven-minute clip of the author reading from Ellis’s Down North, illustrated with original manuscript and diary pages, as well as Ellis’s colour slides.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 27 March 2023