by Diane Payment

Winnipeg, Manitoba

|

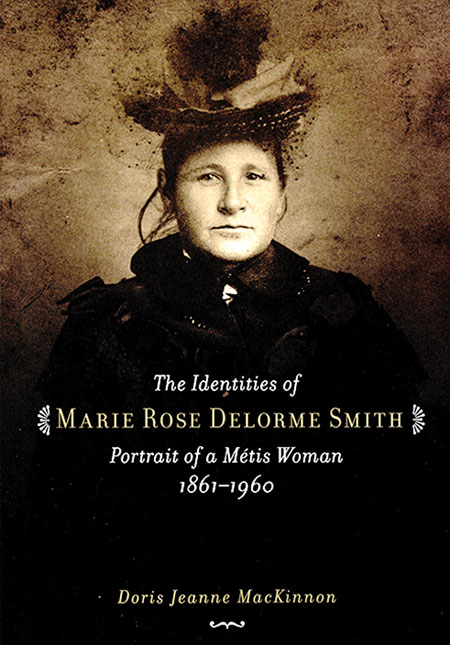

Doris Jeanne MacKinnon, The Identities of Marie Rose Delorme Smith: Portrait of a Métis Woman, 1861–1960. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina, 2012, 208 pages. ISBN 9780889772366, $34.95 (paperback)

Marie Rose Delorme Smith lived a long and productive life. A strong, enterprising and resilient woman, she appears to have privately cherished her Métis heritage, in particular her childhood in Red River, Manitoba and her youth on hunting and trading expeditions in the western plains. For most of her life, however, circumstances led her to identify herself at least outwardly with the dominant Anglo-Canadian majority, as Mary or Mrs. Charlie Smith. The innocent, convent-educated, fifteen-year-old “quarter-breed” (a term she used to describe other “Métis” women of her status) was reportedly “forced” by her mother to marry the much older, rich and “hard living” whisky trader, Charlie Smith. [1] Marie Rose had seventeen children between 1878 and 1904, served “the boss” (her husband), and did woman’s work and more. She essentially ran the Jughandle Ranch, as she had the business acumen and the wandering Charlie was often “absent.” After his death in 1914, she took a second homestead (as the widow of an original homesteader, as women could not obtain a homestead under the Dominion Lands Act) and also ran a boarding house to re-establish the family’s reduced finances and raise her large family.

Marie Rose Delorme Smith lived a long and productive life. A strong, enterprising and resilient woman, she appears to have privately cherished her Métis heritage, in particular her childhood in Red River, Manitoba and her youth on hunting and trading expeditions in the western plains. For most of her life, however, circumstances led her to identify herself at least outwardly with the dominant Anglo-Canadian majority, as Mary or Mrs. Charlie Smith. The innocent, convent-educated, fifteen-year-old “quarter-breed” (a term she used to describe other “Métis” women of her status) was reportedly “forced” by her mother to marry the much older, rich and “hard living” whisky trader, Charlie Smith. [1] Marie Rose had seventeen children between 1878 and 1904, served “the boss” (her husband), and did woman’s work and more. She essentially ran the Jughandle Ranch, as she had the business acumen and the wandering Charlie was often “absent.” After his death in 1914, she took a second homestead (as the widow of an original homesteader, as women could not obtain a homestead under the Dominion Lands Act) and also ran a boarding house to re-establish the family’s reduced finances and raise her large family.

Freed from domestic responsibilities by the 1930s, the energetic and intelligent Marie Rose reflected upon her past and felt she had a story to tell about her “pioneer life” in the west. She wrote mainly about “safe” topics such as the ranching culture, frontier life, and respected Aboriginal (“Indian”) traditions. Related to her history she discussed some controversial events such as the “Rebellion” [2] of 1885, Louis Riel, and the execution of Thomas Scott, but she largely conformed to the official view of the “poor ignorant Halfbreeds” and misguided Riel. She did not acknowledge the active involvement of her Delorme uncles or the views of her sisters, Elisa Ness and Madeleine Gareau, who lived at Batoche during the Resistance. Rather she presented the views of her “loyalist” brother-in-law, George Ness, who opposed the “rebels” and testified against Riel at his trial. It is as if Marie Rose needed to “rehabilitate” her compatriots in the eyes of her Euro-Canadian readers and conform to the official or accepted version of events. One area where she was resolute, however, was in her devotion to the Roman Catholic faith and the support of her mentor, Father Lacombe. Marie Rose was strong-minded and assertive in her personal life, but selective if not fearful of revealing her Métis origins and cultural traditions to outsiders. Considering the enduring racism and intolerance of the early 20th century, it is not surprising that she distanced herself from her Métis heritage. The Métis of Western Canada were effectively silenced, crushed, and humiliated in 1885. Southern Alberta ranching society was particularly anti-French and critical of Aboriginal lifestyles in the decades that followed. Like many Métis of her generation, Marie Rose wanted to be accepted and ensure the integration of her children into mainstream society. She spoke of her decorative beadwork, storytelling, and healing practices, but she did not transmit her Michif French language or sensitive cultural traditions to her children and descendants. Most of her children married into the Anglo-Canadian or immigrant community, and her grandchildren hid or denied their Métis heritage until its resurgence in the late 20th century.

In this way, Marie Rose’s life and behaviour parallel that of other Métis women of her time who did not live in a predominantly Michif French community such as St. Laurent (Manitoba), Batoche (Saskatchewan) or Fort Providence (Northwest Territories). Even in those communities, fear and humiliation forced many women to keep their heads down or assume the identity of their non-Métis family. Despite her “divided loyalties,” one cannot help but admire and respect Marie Rose. She could not reveal her “pensées profondes” (inner thoughts) or Métis world during her lifetime. Unlike now, she lived at a time when it was not popular to be Métis. It was better to be Mary Smith than Marie Rose Delorme.

Doris Jeanne MacKinnon, who was born in St. Paul des Métis (Alberta), may also have a Métis or French-Canadian connection. She is definitely very close to her subject, but careful in offering various interpretations of Marie Rose’s identity and ethnic affiliations. The author skilfully dissects Marie Rose’s memoirs, unpublished manuscripts, and a series of edited articles published in the 1940s. [3] She also met and interviewed family members who provided important “living” context, reminiscences, and photographs. Because of the “stream of consciousness” style of Marie Rose’s writing, the author was faced with the challenging task of interpreting disconnected, incomplete, and at times contradictory narratives. Her use of “informed speculation” based on specific and comparative evidence is a very effective methodology to address these issues. In her analysis MacKinnon also integrated comparative literature on the Métis and biographies of other women. The family tree in the appendix is a key reference to identify Marie Rose’s family connections and provides further insight into her life and legacy.

This book is based on exhaustive and meticulous research and is an important contribution to Métis history. It provides a critical supplement to the romanticized biography written by Marie Rose’s granddaughter, Jock Carpenter, in 1977. [4] There are few life histories written by “ordinary” Métis women, and in this absence their lives must be pieced together primarily through indirect evidence, oral history, and material culture. The book would have benefitted from higher resolution images of Marie Rose’s family and artwork. There are numerous other photographs of Marie Rose’s family and her community of Pincher Creek in archival collections. Additional illustrations and a map of her homeland in the western prairies would also have helped the reader further appreciate her cultural landscape.

1. Marie Rose wrote in her memoirs that she was forced to marry, and the author states that she was sold for $50. Another possible interpretation is that her widowed (but recently remarried) mother wanted to marry off her daughter to an older, well established man. Arranged marriages, especially for young daughters, were common in 19th-century Métis society. It is also possible that Marie Rose, who experienced marriage difficulties, reflected negatively about the circumstances later in life.

2. This is the term used by the author and in Western colonial tradition, but Resistance is the official term used by the Métis today to signify an armed resistance against the Canadian government to defend their rights and homeland. The term used in 1885 was “guerre nationale” or war in defence of the New Nation of the Northwest.

3. See Marie Rose Smith fonds at the Glenbow Institute Archives and the archives of the Kootenai Brown Pioneer Village. A series of articles entitled “Eighty Years on the Plains,” based on her memoirs, but edited by Grant MacEwan, were published in Canadian Cattlemen in 1948-1949. A contemporary and neighbour of Marie Rose, Emma Lynch-Staunton, also published an article based on her memoirs in the Lethbridge Herald in 1941. Marie Rose’s “own voice” or unedited manuscripts were never published.

4. Jock Carpenter, Fifty Dollar Bride, Sidney, BC: Gray’s Publishing, 1977. Ethel (Jock) Carpenter, born in 1933, is the daughter of Marie Hélène Smith Parfitt. She acknowledges her grandmother’s Métis heritage but focusses on her life as a “prairie girl.” It is a more personal piece.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 3 April 2020