by Tolly Bradford

Concordia University College of Alberta

|

Except in rather celebratory church histories like A. G. Morice’s History of the Catholic Church in Western Canada, Christianity has largely been written out of the history of both Red River and western Canada before 1820. [1] Historians have largely assumed that, before formal mission churches arrived in the region, Christianity was not a factor in the lives of people in Rupert’s Land, or in process of colonization. This assumption is based on the belief that the fur-trade era, especially before 1820, was a time period characterized almost exclusively by issues of trade and commerce. While some historians, since the 1970s and 1980s, have recognized that this economic backdrop had social consequences—most notably in the way intermarriage between trader and Native led to the emergence of new Metis communities—religion, and Christianity especially, remains a relatively understudied feature in the history of the west before 1870 and especially before 1820.

In this article, I want to address this gap in the scholarship, albeit in a very limited way. Looking at the period from about 1800 to 1821 when missions formally arrive in Red River, the paper explores how the chief architects of the Red River Colony—the London Committee of the Hudson’s Bay Company and Lord Selkirk—used Christianity to create communities in the colony before 1821. I refer to the London Committee and Selkirk collectively as “the metropolitan elites” because, unlike HBC officers and servants living in Rupert’s Land or Selkirk’s own settlers, the London Committee and Selkirk (at least before 1817) saw Rupert’s Land from their home-base in London, rarely setting foot in the territory. While a larger study may address the way Metis, settlers and Aboriginal peoples likewise understood and used Christianity during the early 19th century, my focus here is on how these metropolitan elites used Christianity. I want to explore what this use tells us about the meaning of religion and Christianity in the West before missionaries began playing a pivotal role in the region after the 1820s and well before they became a decisive force in the colonization of the West by Canada after the 1870s.

Although Selkirk and the London Committee of the HBC had slightly different visions of what constituted a “Christian community,” I argue here that during the earliest years of the 19th century, they both shared a fairly conservative vision of who could and should become a Christian and how Christianity should be used in Rupert’s Land, and in Red River particularly. In brief, these metropolitan elites saw Christianity as a mechanism to describe, order, and retain control over peoples and families that had been born into Christianity and had existing familial ties to the religion through their fur-trading fathers or Scottish upbringing. Most strikingly, neither the Company nor Selkirk saw Christianity as something that should be used to convert Aboriginal peoples and assimilate them into the colony at the Forks. Rather, for Selkirk and the HBC, Christianity was something bred in the bone, not learned through conversion; it was something, which could be used to govern the communities of Metis and British-born settlers living along the Red and Assiniboine rivers, and keep them separate from the “Native” hunters and trappers living outside the colony. This fairly conservative view of Christianity, which seems to fit into the broader patterns of the British Empire, shaped the early beginnings of European religion in the Red River Colony. [2]

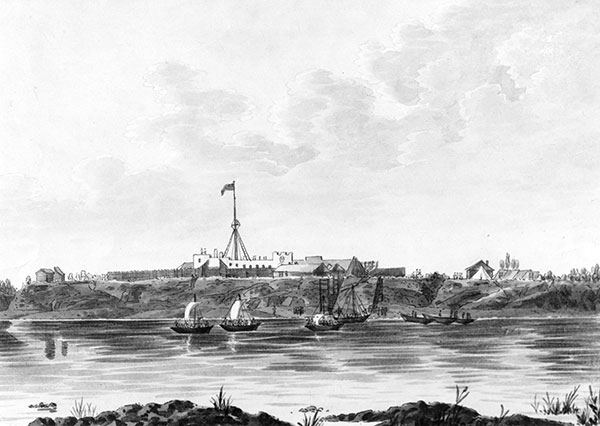

The first group of Selkirk settlers leave York Factory for Red River, August 1812, as painted by Peter Rindisbacher (1806–1834).

Source: Library and Archives Canada, Rindisbacher 7, Acc. No. 1988-250-17.

According to J. M. Bumsted’s recent and very thorough biography of Selkirk, The Earl “appears to have had no visible religious beliefs whatsoever.” [3] This may be true. His life was, it seems, shaped more by the writing of Adam Smith and Thomas Malthus than by the Bible. Indeed, I would agree more with this portrayal of Selkirk than with how he appears in Alexander Ross’ 1856 history of Red River. There, Selkirk is portrayed as a kind of Christian missionary who created Red River, not to settle a group of poor Scots and Irish, but, in the words of Ross, with the objective of “spreading the Gospel, and the evangelization of the heathen.” [4] I do, however, disagree with Bumsted on one point: that he does not acknowledge how Christianity figured into Selkirk’s thinking and extensive writing about immigration schemes dating back to the beginning of the 19th century.

To understand the role of Christianity in Selkirk’s thinking, it is important to recognize that, aside from his scheme to help the poor of Britain, one of Selkirk’s many motivations to resettling Scots and Irish in British North America was to stop what he called the “contagion” of American Republicanism in the British colonies. As he wrote in 1806 about Upper Canada, the influx of Americans (“late-Loyalists”) was, in his mind, altering British society in the colony, threatening to “infect the mass of the people throughout the province” with Republicanism. [5] Selkirk saw a carefully engineered scheme of immigration as a solution to this northward spread of Republicanism. Outlined in letters and pamphlets in 1805 and 1806, he explained how he hoped to resettle large communities of non-English-speaking peoples from Europe in Upper Canada. Under this scheme, the colony of Upper Canada would be divided into different districts, each home to “national settlements” of European immigrants, particularly Highlanders, Dutch and Germans. These settlements, stated Selkirk, should remain “distinct and separate” from one another, and be sites where the “peculiar and characteristic manners [of Highlanders or Dutch or German settlers], should be carefully encouraged.” The point of this scheme was that Upper Canada, once settled by blocks of Dutch, Germans and Highlanders (each kept separate and each retaining their respective language, religion and culture), would be less attractive to the English-speaking American. It was these “national settlements” of non-English speakers, prophesied Selkirk, which would form “a strong barrier against the contagion of the American sentiment,” and settlement. [6]

In this sense, Selkirk did not see migration and settlement as a way to assimilate newcomers into existing Aboriginal or British North American colonial society. Rather Selkirk’s expectation was that the European settler communities he moved from Europe to North America would remain completely intact as they crossed the Atlantic and re-establish themselves in Upper Canada or elsewhere. Although the retention of “national” language and dress were two features that would keep the “old cultures” of these communities alive and unchanged in North America, he also recognized that religion, particularly religious institutions and religious leaders, would be crucial in helping these “national communities” remain cohesive units during and after their transatlantic crossing. [7]

By 1811, as he was preparing his scheme for Red River, traces of the “national community” ideal he had outlined for Upper Canada remained part of his thinking. Although he dropped his insistence on using only non-English-speaking settlers, religion remained an important tool used by Selkirk to help his settlers transplant their culture to British North America. In the “Prospectus” Selkirk published to attract potential settlers, he makes a great deal of the cheap, good-quality land available to immigrants; however, he also devotes an entire paragraph to his promise that the new settlement in Assiniboia would be a place free of the sectarian strife so common in Britain, and especially Ireland, during the 18th century. The Prospectus stated in part that, “The settlement is to be formed where religion is not the ground of any disqualification; an unreserved participation in every privilege will, therefore, be enjoyed by Protestant and Catholic, without distinction.” [8] This would not, however, be a colony without religion. Selkirk also explained to prospective settlers that they would be given a minster of their own denomination: “It is proposed, that, in every parochial division, an allotment of lands shall be made, for the perpetual support of a clergyman, of that persuasion which the majority of the inhabitants adhere to.” [9] Just as in Upper Canada, the Selkirk settlement at Red River would not just allow—but actively encourage—the retention of “old world” cultural and religious practices.

Although not realized before 1818, there were some provisions made by Selkirk to equip his settlers with religious leaders. A Presbyterian minister was assigned to the Scottish settlers, although he remained in Scotland to learn Gaelic and never reached the colony; and a “Rev. Bourke” had been recruited by Selkirk to act as a priest to the Irish Catholics, although he was sent back to Ireland in about 1813. [10] Without these ordained ministers, divine services, marriages and weddings were performed by Miles Macdonell for the Catholics, while Presbyterian rites were carried out by James Sutherland, one of the Scottish settlers. [11] As early as 1816, Macdonell and Selkirk were writing to the Bishop of Quebec to ask that he send a Catholic priest to the region. In line with his ideal of using institutional religion to build and maintain communities, Selkirk felt strongly that a Catholic priest could be used to serve the Canadian and Metis populations of the settlement. “I am fully persuaded of the infinite good which might be effected by a zealous and intelligent ecclesiastic among [the Canadians], among whom the sense of religion is almost entirely lost,” wrote Selkirk. [12] As it happened, an ordained leadership never materialized in Red River until 1818.

Aside from providing leadership to the community, Selkirk, and likely most of the HBC Committee in London, also foresaw that communities that had sound religious leadership would be more likely to become a force of what was called “respectability” in the Red River valley. Somewhat like the way he had described the value of his “national communities” as bulwarks against the lawless Americans, metropolitan elites like Selkirk and the HBC committee members in London expressed hopes that these settlers, particularly the thrifty and principled Scots, would in time, allow these communities to stop the “contamination” of the region by lawless peoples. In Red River, this “contamination” was not attributed to American Republicanism, or even to the “heathen natives” Alexander Ross talks about, but rather to the apparently “lawless” fur traders of the North West Company (NWC). Selkirk expressed an almost prophetic vision of how his poor but energetic settlers would inevitably end the influence of the NWC at Red River. As he wrote in 1816, before Seven Oaks but after years of violence at Red River, “when a body of industrious farmers have once been firmly established, [the settlement] must soon put it out of the power of any lawless…traders to overawe and insult them.” [13] Selkirk further illustrated how this would happen. Through time, he explained, the small settlement he had started at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers would “bring along with it, in due time, an effective police, and a regular administration of justice; that [will be a threat to men] who maintain a commercial monopoly by the habitual exercise of illegal violence… ” [14] While Christianity is not mentioned, we have seen that at the base of this “flourishing settlement” was, at least in Selkirk’s mind, religion—particularly the “national” religions of the settlers, complete with clergy and church.

At the same time that Selkirk was working to create a “flourishing settlement” at Red River comprised of distinct ethno-religious blocks, the London Committee of the Company was using Christianity to create a slightly different kind of Christian community at its hinterland posts throughout the North-West. Stretching back to at least the mid-18th century, Christianity—in rhetoric if not reality—had always been a part of the post society. Throughout the 18th century, the HBC, although a business, encouraged post factors to use religion as a way to retain the social structure and social order in the forts. According to Scott Stephen, divine services had a kind of double purpose in the 18th-century post society—to remind servants of the hierarchy of the fort (with God at the very top, presumably), and to encourage “more virtuous” behaviour amongst the servants. Interestingly, Stephen also suggests that in the months after periods of labour unrest at forts, post factors made a particularly vigorous effort to tell the London Committee that they were holding regular divine services at the post, and demanding “virtuous” behaviours from the servants. [15] While this pattern of reporting suggests that the on-the-ground reality of post life may not have been as religious or virtuous as the London Committee hoped, it does reveal that religion, or at least the rhetoric about it, was a central pillar of Company operations well before 1800.

After 1800, the HBC had somewhat modernized its use of Christianity at the posts. Due to demands from HBC servants that their children be given an education at the post, and due to the growing evangelical mood amongst a few members of the London Committee, Christianity started to have a dual purpose at its posts: on the one hand, divine services and the fear of God would continue to be used to assert the hierarchy of post society, with the governor, the Committee, and ultimately God at the top; on the other hand, Christianity should be used to assimilate the mixed-ancestry children of post families into a form of Britishness. [16]

This new use of Christianity marked a significant departure from the way Christianity had been used in the past. In the 18th century, Christianity was something that shaped the world within the post walls. Neither the original charter of the HBC nor directions from London seem to make mention of bringing Christianity to Aboriginal communities outside the post walls. [17] However, by the early 19th century, at least amongst the Committee in London, there was some consideration being made about the way Christianity could be brought to serve the wider “fur trade society”—including both the children and wives of servants, and the “natives” of the territory. In 1808, the Committee noted, for example, that they may create “Schools under the direction of Clergymen at the Company’s several Factories in Hudson’s Bay for the purpose of instructing the native Youths of both Sexes would tend greatly to promote the cause of Religion & Virtue.” [18] The purpose of the schools was clarified a few weeks later when the London Committee suggested that the purpose of a school was two-fold. It would “instruct the Children of the Servants & also the Children of such native Families as may be desirous of reaping the benefits of Civilization & religious Instruction.” [19] However, as I show below, the focus placed by the HBC on instructing “native Families” was limited and, if anything, faded over the course of the 1810s and 1820s.

This ideal of the Company school at Bayside posts was never realized in a systematic way. Although there were a few schoolteachers assigned to some of the larger posts, the plan of establishing a Company school at the centrally-located Cumberland House never came to pass. [20] What these plans do suggest, however, is that the Governor and Committee in London, knowingly or not, were suggesting a change to post society. In this new vision, Christianity would absorb non-whites, especially mixed-ancestry children with ties to the post, into the sphere of the HBC, and in the process create a new kind of post society that was multi-ethnic, Christian, and led by a white HBC officer class. In many ways, this envisioned post society—hierarchal, Christian, and multi-ethnic—is evident in the way the Colony at Red River took shape after 1821. This was no accident. The HBC carefully arranged that its servants and families once retired or made redundant after the merger of the NWC and HBC, should not be allowed to stay in the hinterland but rather should be gathered at Red River and placed in the care of a Church.

The idea of using Christianity to make new communities of post employees at Red River was outlined by Committee member John Halkett after a visit to Red River in the early 1820s. Writing back to his colleagues in London, Halkett explained that all retired employees and their Metis families should be sent to Red River at the Company’s expense. The reason for the decision to relocate the Metis families was principally economic: the HBC did not want retired or discharged employees interfering with the fur trade and its relations with Aboriginal traders. In the words of historian E. E. Rich, Halkett and the Committee in London felt it was a “necessity to get men who ought to be discharged from the fur trade to take up land at Red River instead of hanging around the posts, tempting the Indians to trade and inevitably putting something of a strain upon the supply system by their demands.” [21] Once resettled in Red River, these HBC families should be placed under the “care” of either the Roman Catholic Mission or, in the case of Protestant families, the newly arrived Church Missionary Society.

While there was a philanthropic and humanitarian aspect to the HBC’s plan to relocate families to the parishes of Red River, the main factor driving this plan to place its discharged employees with missions was the desire for the Company to retain authority in the North-West. Not only would this plan make it impossible for retired traders to “hang around the fort and tempt Indians to trade,” but also it would offer the Company a way to control the Colony. By using missionaries to act as patriarchal figures to the retiring fur-trade families, the company believed it could recreate at Red River the multi-ethnic, Christian and hierarchal post society that had characterized the hinterland posts. This plan, in a sense, would relocate fur-trade society from the post to the parish.

By the late 1810s, then, Selkirk and the HBC had slightly differing visions of how the Colony at Red River should be shaped by Christianity. While Selkirk tended to see communities as ethnic blocks, each following its own version of Christianity, the HBC, given its long experience of the post society, saw their Christian communities as multi-ethnic, comprising both British-born and Aboriginal peoples. However, more important than these differences was the way Selkirk and the London Committee shared a sense that Christianity was a kind of glue that could be used to bind together their communities. Indeed, both seemed to see Christianity as a key marker differentiating Aboriginal peoples living outside the settlement from the mixture of communities that settled in the Red River Colony.

Selkirk seems quite clear on this point: he makes no reference to integrating Aboriginal peoples—or even other Europeans—into his settlement of Scottish Presbyterians. He does, in an 1814 pamphlet, outline a vague plan for Indian education. However, as this pamphlet argued, the transformation of Aboriginal peoples into settled farmers should be achieved without the direct integration of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples. Instead, selected Aboriginal boys should be brought to Industrial schools at settlements like Red River, and there taught agricultural and industrial skills that they could then bring back to their community. There is no mention of either outright cultural assimilation or a concerted attempt at Christianization. [22] While Selkirk does suggest that a missionary could in the future be used to recruit these potential students, he thinks that, in the short term, HBC officers and servants could “visit the wandering tribes, and… call their attention to the utility of the improvements recommended to them.” [23] This was a vision of a mission project without missionaries, without overt references to Christianization, and without a goal of absorbing and assimilating Aboriginal peoples. Selkirk wanted them to change the way they used the soil, but he did not seem interested in interfering with their spirituality.

For its part, between 1800 and the 1820s, the HBC Committee seemed to be moving further away from supporting mission activity in the hinterland of the North-West. Although the London Committee had suggested that prayers and Christian education at posts should be open to those “as may be desirous of reaping the benefit of Civilization & Religious Instruction”, by the 1820s, and especially in reference to Red River, the Governor and Committee seemed, if not opposed, then certainly not prepared to support, the evangelization of Christianity amongst peoples not otherwise connected to a parish at Red River through family ties. In 1819, when John West was recruited to be deacon for the Company, he was told to restrict himself to serving only the families of Company men at Red River. As recorded in the London minute book, West was hired for the “purposes of affording religious instruction and consolation to the Companies [sic] retired Servants & other Inhabitants of the Settlement, and also of affording religious instruction & consolation to the Servants in the active employment of the Company upon such occasions as the nature of the Country and other circumstances will permit.” [24] No mention is made of evangelizing the Aboriginal population outside the colony. As those familiar with West’s short stay in Red River will know, his few attempts to evangelize created considerable friction between West and local HBC authorities, especially George Simpson. Indeed, it was not really until 1840 that Catholic and Protestant missionaries were able to use HBC transportation support to move out of the colony and begin evangelizing to the north and west. Until that time, although many Aboriginal and Metis families were drawn to the missions at Red River, in the opinion of many HBC officers in Rupert’s Land, and at least some members of the London Committee, Christianity should be kept inside the post walls and within the boundaries of the Red River Colony.

The Cathedral (left) and Nunnery (right) at St. Boniface, as seen from the west bank of the Red River, circa September 1858.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, H. L. Hime 6, N10833.

Historians of the British Empire often talk about the period after the early 1800s as a period marked by the slow shift to “the Second British Empire.” This Second Empire was supposedly marked by the gradual change in the nature of the British Empire. While there is some debate as to the timing of this move towards a “new” Empire, most scholars agree that by the 1830s the Empire was emphasizing new things—most especially more migration from Britain to its colonies, an agenda of liberalism, free trade, and, by the 1840s, a concerted movement to convert indigenous peoples to Christianity. [25] Unlike the previous decades of simply commercial imperialism, during this Second Empire the British aimed not just to colonize the material resources of spaces like western Canada, but also to colonize the space of the region and the minds of its peoples. While this periodization certainly holds for places like the Cape Colony of South Africa, Upper Canada and India, in some ways Red River remained stuck in the First Empire until at least the 1850s, and arguably into the 1870s. While there was a brief wave of emigration from Britain to the West under Selkirk, many other features of the West remain stuck in an 18th-century vision of empire. The fur trade and the monopoly of the Hudson’s Bay Company were still the main features of British presence in the prairies, and Christianity rarely moved beyond the boundaries of settlement. The fact that John West, and CMS missionaries until the late 1840s, were hired to work in the colony and were not permitted to go beyond it suggests the Company—and George Simpson in particular—were still working by the rules of the 18th and early 19th centuries: that Christianity was the religion for the “civilized” settlers at Red River and hinterland posts, not a religion to be propagated throughout Aboriginal camps. Still tethered to the banks of the Red and Assiniboine, they were charged with preaching to the converted, rather than preaching to convert. Was this due to the tyranny of geography or to the tyranny of George Simpson and his Company’s attachment to a vision of Christianity that promoted the control, order and containment of the Aboriginal peoples of the west?

Whatever the reason for this restrictive use of Christianity by Selkirk, Simpson and the London Committee, it is clear that the early history of religion in Red River reminds us of the distinct patterns of colonization in the Prairie West. For instance, the story of missions in the colonization of western Canada is different from the role of Christianity in what would become central Canada. There, the concerted effort to convert Indigenous peoples to Christianity began in the 17th century and continued under the guidance of various Catholic and Protestant organizations through to the 20th century. In the Prairie West, Christianity arrived later and for different reasons. It was first and foremost, a tool for the making of settler society, and only after the mid-1800s would it become a tool for the cultural conversion of the Aboriginal populations. Selkirk’s dream of a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural world in the West provided a limited role for the evangelization and conversion of Indigenous Peoples to Christianity. Religion, in this instance, was meant to define communities, not to change them.

1. See the early chapters of Adrien Gabriel Morice, History of the Catholic Church in Western Canada, from Lake Superior to the Pacific (1695-1895), Toronto: The Musson Book Company, 1910.

2. A convincing argument about the relatively “conservative” nature of the empire between the 1780s and 1820s is made in C. A. Bayly, Imperial Meridian: The British Empire and the World, 1780–1830, London: Longman, 1990.

3. J. M. Bumsted, Lord Selkirk: A Life, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2008, p. 157.

4. Alexander Ross, The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress and Present State. With Some Account of the Native Races and Its General History to the Present Day, Minneapolis: Ross and Haines, 1856, p. 1.

5. Thomas Douglas, Earl of Selkirk, “Observations on the Present State of the Highlands of Scotland, with a View of the Causes and Probable Consequences of Emigration,” J. Ballantyne & Co. for A. Constable and Co., 1806, p. 162.

6. Ibid., p. 162.

7. Bumsted, Lord Selkirk, p. 139.

8. [Lord Selkirk], “Prospectus for the Red River Settlement,” in, John Strachan, A letter to the Right Honourable the Earl of Selkirk, on his settlement at the Red River, near Hudson’s Bay. London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown etc, 1816, p. 71.

9. Ibid., pp. 71-72.

10. A. Begg, History of the North-West, Toronto: Hunter, Rose & Co, 1894.

11. Morice, History of the Catholic Church in Western Canada, from Lake Superior to the Pacific (1695–1895), chap. 5; Ross, The Red River Settlement, pp. 30–31.

12. Morice, Ibid., p. 90.

13. Selkirk, “A Sketch of the British Fur Trade in North America; with Observations Relative to the North-West Company of Montreal, 1815” in The Collected Writings of Lord Selkirk, Vol. 2, 1810-1820, ed. J. M. Bumsted, p. 95.

14. Ibid., p. 96.

15. Scott Stephen, “Masters and Servants: The Hudson’s Bay Company and Its Personnel, 1668–1782”, Unpublished Manuscript. Thank you to Scott Stephen for allowing me to look at this manuscript. Although not commenting on the role of religion specifically, one of the most thorough discussions of the importance of hierarchy and authority in 18th-century HBC post society is also made in, John Elgin Foster, “The Country-born in the Red River Settlement,” PhD, University of Alberta, 1973, ch. 1.

16. Foster, “The Country-born in the Red River Settlement”, p. 75.

17. Scott Stephen, e-mail message to author, 7 May 2012.

18. Governor and Committee of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Minutes, quoted in, Archives Department Research Tools 16, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives (HBCA), Archives of Manitoba, Winnipeg, RG20/6/16, 2 March 1808.

19. HBCA, RG20/6/16, 16 March 1808.

20. Mention of plans to start a Company school at Cumberland are made in HBCA RG20/6/16, 31 May 1809.

21. E. E. Rich, The History of the Hudson’s Bay Company, 1670-1870, vol. 2, 2 vols., London: Hudson’s Bay Record Society, 1958, p. 429.

22. Thomas Douglas, Earl of Selkirk, “Untitled Pamphlet on Indian Education, ca. 1814”, in The Collected Writings of Lord Selkirk, Vol. 2, 1810-1820, pp. 3-6.

23. Ibid., pp. 5-6.

24. Governor and Committee of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Minutes, 13 October 1819, quoted in, Archives Department Research Tools 16, HBCA, RG20/6/16.

25. For discussion and debate about the “Second British Empire”, and the changing place of Christianity in the Empire, see C. A. Bayly, Imperial Meridian: The British Empire and the World, 1780–1830, London: Longman, 1990); P. J. Marshall, “Britain Without America—A Second Empire?”, in The Eighteenth Century, vol. 3, The Oxford History of the British Empire, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 576–595; Andrew Porter, Religion Versus Empire?: British Protestant Missionaries and Overseas Expansion, 1700–1914, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004; and, Tolly Bradford, Prophetic Identities: Indigenous Missionaries on British Colonial Frontiers, 1850–75, Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012, pp. 6–7.

Page revised: 6 January 2018