by Paul G. Thomas

St. John’s College, University of Manitoba

|

Political memoirs represent a highly popular form of historical literature because history and politics are narrated in a highly personalized manner. Personal accounts of events can add new perspectives, provide an authentic feel for the occasion and enliven the analysis of past developments and trends. On the other hand, memoirs can present problems, such as the risks of bias, selfcongratulation and a selective recounting of events.

Political memoirs represent a highly popular form of historical literature because history and politics are narrated in a highly personalized manner. Personal accounts of events can add new perspectives, provide an authentic feel for the occasion and enliven the analysis of past developments and trends. On the other hand, memoirs can present problems, such as the risks of bias, selfcongratulation and a selective recounting of events.

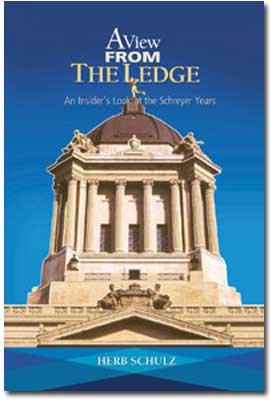

This memoir, written by Herb Schulz, former special assistant to Premier Edward Schreyer from 1971 to 1977, reflects both the strengths and weaknesses of the genre. It is an intensely personalized account of the Schreyer era. There is much to take issue with in the book, but it offers readers a valuable and too rare perspective on the inner workings of government and the linkages to the wider political process. Perhaps because of the secrecy inherent in cabinet-parliamentary government and the small market for political books in Manitoba, relatively few politicians have written about their experiences in public life and the political science literature is limited also. This is least true for the first New Democratic Party government elected in 1969, which, following its surprise victory, came to power with an ambitious policy agenda. The story of moving that agenda forward as told by Mr. Schulz adds significantly to our understanding of the dynamics of leading and governing in the province.

As a close observer and frequent commentator on political events during the Schreyer era, I knew of Mr. Schulz by reputation but, to the best of my recollection, I have never met him. He was a controversial figure, both because of his contrarian mindset, his confrontational personality and the strategic location he occupied as the “gatekeeper” controlling the flow of people and information to the Premier. His account of how he wielded his undoubted influence within the inner circle raised for me the issue of what principles and standards should govern the behaviour of political advisors who occupy a kind of “constitutional twilight zone” in the governing process. Such advisors are not elected politicians who are answerable to the public, nor are they career public servants who answer to responsible ministers, yet they are paid from the public purse and are often involved with key political, policy and even administrative decisions made in government. Given the potential risks of relying too heavily on the advice and leadership of such individuals, governments need to be careful whom they appoint and how they control their political advisors.

Mr. Schulz was a high-risk appointment. The fact that he was the brother-in-law to the new Premier raised a few eyebrows. Raised in a “political” home (his father was at times an MLA and MP), Mr. Schulz was always an activist who seemed to relish controversy. During his busy life he has found time to run a farm, take an active role in farm organizations, become a graduate student in history, lecture at the university and write another book on agriculture policy and politics.

This book reflects Mr. Schulz’s reputation. It is intelligent (in a somewhat narrow way), opinionated, candid, combative, theatrical, self-promotional and verbose. It is also an erudite and highly readable book, which provides insights into the strategies and tactics of leading and governing in Manitoba. It is laden with colourful and humourous anecdotes which provide an authentic feel for life at the centre. The book might be described as an insider’s account written by an outsider. Over his 70 months of serving the Premier, Schulz contributed to important decisions, but also managed to antagonize a great many people inside government, the NDP and many parts of Manitoba society because of the aggressive promotion of his own ideas and the use (some would say the abuse) of the authority of the Premier. The book stops at 1977 when the NDP government lost power to the Progressive Conservatives led by Sterling Lyon.

The relationship with Premier Schreyer is central to Mr. Schulz’s account. He describes the Premier as “studious, soft-spoken, cerebral, introspective, innerdirected and reserved” (23). His speaking style is described as “ponderous” and “slightly sanctimonious” (24). This is the description of a man whom Mr. Schulz clearly admired and a leader who was so hugely popular with the public that his leadership appeal accounted a great deal for the surprise election in 1969 of the NDP government. When the NDP tried unsuccessfully for a third term in 1977, it ran under the slogan “Leadership You Can Trust,” a slogan apparently invented by Herb Schulz. Throughout the book there are lengthy passages of heated arguments between the Premier and his opinionated special assistant about matters of philosophy, policy, personalities and political tactics. There are also many stories scattered throughout the book about Mr. Schulz’s attempts to intimidate and pressure others into doing what he thought was the right and/or politically smart action.

Edward R. Schreyer, Premier of Manitoba, 1969-1977.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Personalities - Schreyer, E. R. 1, 1969, N13920.

With an introduction, epilogue and forty chapters (all relatively short), the book provides a reasonably comprehensive account of the Schreyer years. Not surprisingly, it deals mainly with the dramatic moments, but also provides some glimpses into the “ordinariness” of daily political life. The account is often detailed, including “dialogues” with others which the author describes as “composites” derived from his memory apparently. He has clearly researched government files and media reports to support his strong views on the political and policy issues of that time and the list is a long one: Medicare, Autopac, hogs, the loss of the Winnipeg Jets, aboriginals, labour relations, high profile crown corporations and the civil service. There is some discussion, but no in depth analysis, of the 1973 election when the NDP was re-elected but did not achieve the large majority anticipated. Many readers will disagree with Mr. Schulz’s views on events and issues, but they will not be bored by his provocative opinions.

Despite the government’s extensive record of reforms, Mr. Schulz was often frustrated by the political timidity and willingness to compromise on the part of the Premier and his cabinet. In one of the most insightful lines in the book he writes that “policy goals so clear while in opposition become blurred, the path to them previously arrow-straight becomes serpentine and the time parameters for their implementation … recede into the distance” (177). Anyone who makes the transition from an activist in an advocacy group, or even from the status of a third party in the legislature, to controlling the reins of power would be similarly forced to recognize the necessity for tough choices, compromises and the accommodation of varied interests and values, especially in a diverse, “have less” province like Manitoba with its “small c” conservative political culture. All “would-be” political power brokers should take note of this fundamental lesson about the realities of governing. There is plenty of evidence to support it in this very good book.

See also:

Memorable Manitobans: Herbert “Herb” Schulz (1926-2014)

Page revised: 12 October 2014